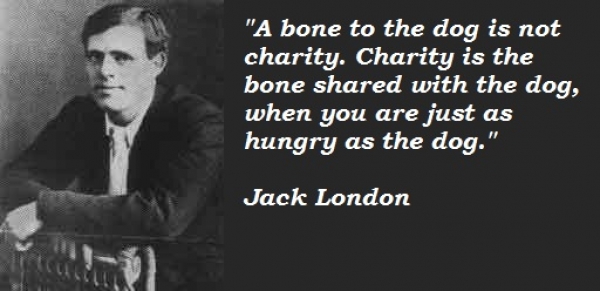

Yours for the Revolution: the life of Jack London

John Green introduces the life of Jack London.

There is a hullabaloo around the quincentenary this year of Shakespeare’s death, but Jack London’s centenary appears to have been forgotten. Yet in his lifetime he became one of the world’s first celebrity writers, and is undoubtedly one of the great novelists of the 20th century as well as an articulate proponent of socialist and progressive ideas.

His incredible life reads like a Boys’ Own fantasy. He was a man driven by raw passion and anger. Born in San Francisco in 1876 as an illegitimate child, he would die aged only 40. But what a mercurial life and creative energy he packed into those short 40 years.

His mother gave him to a black former slave woman to bring up, before she married and was able to take him back into her own care. Jack’s childhood of poverty marked him for life, but he was a boy full curiosity, who refused to let his poor background prevent him gaining knowledge. In 1880 discovered the local public library in Oakland and devoured the books he found there. One of them was a dog-eared copy of The Communist Manifesto, and reading it changed his life irrevocably. In his notebook at the time, he wrote:

The whole history of mankind has been a history of contests between exploiting and exploited… the exploited cannot attain emancipation from the ruling class without once and for all emancipating society at large from all future exploitation, oppression, class distinction and class struggles.

During his school years, he spent his spare time in a saloon bar on the waterfront and when he told the owner he wanted to go to university and become a writer, the owner lent him the money to do so. I don’t know if he was ever repaid, but it was certainly a fruitful investment, as his protégée went on to become a celebrated and wealthy writer. At aged 13, he was working in a cannery for 12-18 hours a day, but he was not cut out for such a life, and was determined to better himself through a devotion to literature.

London soon quit his studies at UCL, Berkeley in 1897, aged 21 after being rejected by his assumed father, an astrologer named William Chaney. He wrote to Chaney but the latter denied paternity and London was devastated. After leaving college, he headed for the Klondike during the gold rush boom. His harsh experience there would give him the raw material for his first stories. To get to the Alaska he made a journey of 2,500km alone in a rowing boat, but turned his experience into a successful short story. His 1903 novel, Call of the Wild, also based in Alaska, was sold to a newspaper and the book rights to Macmillan. It was the book that would win him rapid renown.

Before he was earning enough money from his writing, though, he borrowed money from his foster mother to buy a small sloop and became an oyster pirate in the Bay. This boat was very soon damaged beyond repair, so he signed on as poacher-turned-gamekeeper for the California Fish Patrol. Then later he joined a sealing schooner bound for the coast of Japan. Once he’d managed to establish his credentials as a reporter, he was commissioned to write about the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 as a war correspondent.

What animated Jack London’s life, says one of his biographers, Alex Kershaw, was

above all, a hope that one day poverty and social injustice would decrease, not increase; that the environment would not continue to be regarded as a resource to be continuously exploited; that humanism would one day triumph.

He was driven by passion, anger and a determination to live life to the full. He played hard and drank hard. Already by the age of sixteen he had experienced more than most people do in a lifetime.

After returning to Oakland from the gold fields of Alaska, his health was in bad shape, but he managed to make a fairly quick recovery. Oakland in 1893 found itself the focus of a war of a different kind, one between the bosses and the longshoremen. Witnessing those brutal struggles helped turn London into a socialist activist. He took on gruelling jobs in a jute mill and in a railway power plant, and joined Kelly’s Army – a mass demonstration movement by unemployed workers.

At the same time he was working incredibly hard to get more of his stories published, submitting one after the other to magazines, and was soon making good money at it. His semi-autobiographical novel Martin Eden reflects that period. He cut his teeth in the burgeoning world of magazines, selling his adventure stories widely and establishing a reputation. He would become one of the first fiction writers to obtain worldwide celebrity and a large fortune from his fiction alone.

More than any North American writer, Jack London had an insatiable appetite for life. He often said he preferred living to writing, and by the age of 16 he had experienced more than most people do in a lifetime. He was always searching for new ideas, new challenges. His thirst for travel took him across several continents and inspired his best fiction.

He also embodied the promise of socialism in his life and writing. He exposed capitalism’s evils, its decimation of the workforce through ruthless profit-making. In some of his most powerful prose, he showed how expendable people are in the process of increasing a governing elite’s wealth.

His stories have been used as the basis for film scripts in countries around the world and in different versions, including Sea Wolf, White Fang and Call of the Wild, set in the Klondike gold-rush era, the semi-autobiographical Martin Eden as a TV mini-series as well as his dystopian iconic novel The Iron Heel.

He was an atheist, an active supporter of the Wobblies, joining the Socialist Labor Party in 1896 and then the Socialist Party of America. He also ran as a socialist candidate for mayor of Oakland.

As London explained in his essay How I Became a Socialist, his views were influenced by his experience ‘with people at the bottom of the social pit’. His optimism and individualism faded, he said, and he vowed never to do more hard physical work than necessary. He wrote that his individualism was hammered out of him, and he was politically reborn. He often closed his letters ‘Yours for the Revolution’.

His progressive political views were somewhat tainted for some by his fascination with a mix of Darwin’s and Nietzsche’s ideas, and the concept of a super race. However, for London this was not in the Nazi sense of one race dominating others, but the idea of everyone become ‘super’ by natural selection. Despite being brought up by a black surrogate mother, he did feel the white Anglo-Saxon people were probably superior to others, particularly the coloured peoples. While such attitudes are inexcusable, they can be explained and understood in the US context and atmosphere of the time. However, they rarely if ever influenced his writing and he could hardly be characterised as a racist in terms of hating or discriminating against others. For him class and the class battles were always central.

As a journalist he wrote an impassioned study of poverty in London’s East End, The People of the Abyss, which prefigured Orwell’s similar Down and Out in Paris and London. His burning indignation came through in so much of his reporting. His reminiscences as a drifter bumming it across America were written long before Woody Guthrie, Jack Kerouac, John Steinbeck and others did the same. What comes across in his novels is his first hand experience and understanding of the lives working people and the poor lead. He draws powerful, three-dimensional characters, full of anger, passion and vitality.

London was also a pioneer of environmental awareness. He urged Americans to look for salvation in the wide open spaces, not the canyons of Wall Street, and he led by example. On his farm he introduced many methods that are now common practice on organic farms. He developed the use of liquid manure and hollow block silos as well as pioneering the cultivation of nitrogen replenishing crops like Alfalfa. He was an early animal rights activist, campaigning against cruelty to circus animals.

In 1915, a year before he died, he said in an interview he gave to a journalist from Western Comrade: ‘I became a socialist when I was seventeen years old. I’m still a socialist, but not of the refined school of socialism’. He had by then become disillusioned with the ability of the socialist movement to bring about revolutionary change. This viewpoint is eloquently expressed in his dystopian apocalyptic novel The Iron Heel , published in 1908. It depicts the USA governed by a neo-fascist regime, and the author argues that socialism is the only means of avoiding such a future. It is a forerunner of 1984 and similar dystopian novels. It is one of the most powerful evocations of what can happen to society run by unscrupulous capitalists, determined to maintain their power and privilege. He foresaw German fascism as no other writer did.

He was an avid surfer, and his articles about surfing introduced the sport to America for the first time. He is still celebrated as a cult hero on the beaches of Waikiki in Hawaii.

In 1914 he was sent as a was a war correspondent to Mexico, and following his time there wrote a short story, The Mexican, which has as its hero a Mexican worker who survives a massacre to join the revolution, to free his country of such unscrupulous factory and land-owners.

In 1915 his wife, Chamian, persuaded him to spend time in Hawaii, a relaxing and healthful respite for the two of them. But London's greatest satisfaction came from running his ranch, althogh his ambitious plans kept him in debt and under pressure to write as much as he could in order to pay them off, as well as help out friends and relatives. His determination to write at least 1000 words a day, his continued high consumption of alcohol and unhealthy life style eventually took its toll. But right to the end of his life he was full of bold plans and boundless enthusiasm for the future. When he died, words of grief poured into the telegraph office in Glen Ellen, where he lived, from all over the world.

Ernest Hopkins in the San Francisco Bulletin on December 2, 1916, wrote this:

No writer, unless it were Mark Twain, ever had a more romantic life than Jack London. The untimely death of this most popular of American fictionists has profoundly shocked a world that expected him to live and work for many years longer.

London deserves to be remembered for much more than for his infatuation with surfing, or as a maverick or confused individualist of only historical interest for us today. His works should be read widely, and find a place of honour on every progressive’s bookshelf.

John Green

John Green is a journalist and broadcaster. He has authored and edited several books and anthologies on a wide range of subjects including political biographies, labour history, poetry, natural history and environmental affairs.