The Fall of Paris, by Ilya Ehrenburg

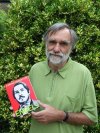

John Green introduces The Fall of Paris by Ilya Ehrenburg (1943), and presents a brief biography of the author. Image above: Ilya Ehrenburg with Red Army soldiers, 1942

I have just re-read The Fall of Paris by Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg. And what a re-discovery it has been! Few people today will have heard of this novel or the author, although he was one of the Soviet Union’s most renowned 20th century writers.

I was struck particularly by how pertinent this novel still is for the times we are living through today. It is also one of the most powerful examples of an accomplished socialist-realist novel.

In it, Ehrenburg describes the decay and eventual collapse of French society between 1935 and the German occupation in 1940. He was living in France during those crucial years before the Nazi invasion, and meticulously describes life in the capital city, as events unfold and the danger of war edges ever closer.

He adopts a traditional story-telling mode, with an anonymous third person narrator and a straightforward chronology of events. His protagonists are taken from all walks of life, classes and political backgrounds, but in his clever intertwining of their lives he reveals the social forces that ultimately determined the course of history.

There is the opportunist Radical Party politician Paul Tessa, with his ailing, devoutly Catholic wife; his wastrel son and a daughter who is so revolted by his opportunistic politics that she leaves home to join the communists; there is Breteuil, the unscrupulous fascist leader; Pierre Dubois, the principled socialist engineer in a large aircraft factory, his friend André, the apolitical artist; Michaud, the militant worker who goes to fight in the Spanish Civil War and Desser, the wealthy boss of the factory, as well as many minor characters.

Ehrenburg meticulously deconstructs the political machinations and battles that determined the trajectory of France’s Popular Front government, its supine abandonment of Republican Spain, its capitulation to the Nazis and its eventual demise. The background is true to life, with leading politicians, artists and public figures given their real names; only the novel’s protagonists are fictitious, but come vibrantly alive in Ehrenburg’s descriptions and dialogues.

This is no simplistic story-telling, with black and white characters, goodies and baddies – his characters are portrayed with all their contradictions, their strengths and weaknesses. The novel has all the traditional ingredients of romance, drama and intrigue, but incorporated realistically and believably.

Although it has since been swept under the carpet, it is salutary to be reminded that well before the Nazi invasion of France, the country had a flourishing fascist movement and that a fascist coup was a distinct possibility in the 1930s, while the governing and opposition parties continued to bicker and squabble fruitlessly among themselves. Ehrenburg demonstrates how the French government’s capitulation to Hitler, whether in Spain or over the Sudetenland, enhanced his sense of invulnerability and fed his voraciousness.

Ehrenburg quotes verbatim from the broadcast given by the Minister for Home Affairs, lying blatantly to the nation about France’s preparedness for war:

‘Never before have the skies of France see such a powerful air-force … never before has the soil of our country known such thundering hordes of tanks … we are working day and night to increase our gigantic armaments …’

At the same time the minister knows full well that the country has very few planes and tanks, and that instead of workers working overtime in the arms factories, the government has been arresting hundreds of communists and suspected communists, and keeping them in concentration camps, thus disrupting production. It all smacks very much of Boris Johnson’s lies about the war on Covid that ‘we are winning and leading the world’ despite the largest death toll per head of any country.

This is not a didactic book, but it does offer valuable insights into society and politics. His characters are colourful and three-dimensional, and his descriptions of French life are highly evocative. Despite it being written over half a century ago it is not simply of historical interest. It has retained its sense of taking the pulse of history and the individuals it describes are still around us today – as is the threat of fascism and the venal political manoeuvring of opportunistic politicians.

Short Biography

Ilya Ehrenburg was born in Kiev into a Lithuanian-Jewish family. When Ehrenburg was four years old, the family moved to Moscow, where his father had been hired as chief of a brewery. At school, he met Nikolai Bukharin and the two remained friends until Bukharin's death in 1938 during the purges.

In the aftermath of 1905 Ehrenburg became involved in illegal activities of the socialist opposition. In 1908, when he was only seventeen, the tsarist secret police arrested him for five months. Finally he was allowed to go abroad and chose Paris for his exile.

In Paris, he moved in Bolshevik circles, meeting Lenin and other prominent exiles. But soon he felt more attracted to the bohemian life in the Paris quarter of Montparnasse. He began to write poems, regularly visited the cafés of the quarter and became friends with many artists, including Picasso, Rivera and Modigliani.

During the First World War, Ehrenburg became a war correspondent for a St. Petersburg newspaper. He wrote a series of articles about the mechanized war that later on were also published as a book - The Face of War.

In 1917, after the revolution, Ehrenburg returned to Russia. In 1920 he moved to Kiev, where he experienced four different regimes in the course of one year: the Germans, the Cossacks, the Bolsheviks, and the White Army. After antisemitic pogroms, he fled to Koktebel on the Crimea, where his friend from Paris days, Voloshin, had a house.

Finally, Ehrenburg returned to Moscow. He became a cultural activist and journalist who spent much time abroad as a writer. He wrote modernistic picaresque novels and short stories which were popular in the 1920s. Ehrenburg also continued to write philosophical poetry.

As a friend of many of the European Left, Ehrenburg was frequently allowed to visit Western Europe and to campaign for peace and socialism. He arrived in Spain in late August 1936 as a correspondent for Izvestia and was involved in writing propaganda and reporting on military activity. In July 1937 he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the war, held in Spain and attended by many renowned writers including Malraux, Hemingway, Spender and Neruda.

Ehrenburg was offered a column in Krasnaya Zvezda (the Red Army newspaper) days after the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. By the end of the war, he had published more than 2,000 articles in Soviet newspapers.

In 1954, Ehrenburg published a novel titled The Thaw that challenged the limits of censorship in the post-Stalin Soviet Union. It portrayed a corrupted and despotic factory boss, and told the story of his wife, who increasingly feels estranged from him, and the views he represents. In the novel, the spring thaw comes to represent a period of change in the characters' emotional journeys, and when the wife eventually leaves her husband, this coincides with the melting of the snow. Thus, the novel can be seen as a representation of the political thaw, and the increased freedom of the writer after the 'frozen' political period under Stalin.

While a whole number of other Jewish intellectuals suffered considerably under Stalin, and many were killed, Ehrenburg was left unscathed. It has been said that Stalin was so taken with his novel The Fall of Paris that he held a protective hand over him. He was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize in 1952.

Ehrenburg is particularly well known for his memoirs (People, Years, Life in Russian, published with the title Memoirs: 1921-1941 in English), which contain many portraits of interest to literary historians and biographers. In this book, Ehrenburg was the first legal Soviet author to mention positively a lot of names banned under Stalin.

Ilya Ehrenburg's grave

Ehrenburg died in 1967 and was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, where his gravestone is adorned with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend Pablo Picasso.

John Green

John Green is a journalist and broadcaster. He has authored and edited several books and anthologies on a wide range of subjects including political biographies, labour history, poetry, natural history and environmental affairs.