Summer Poetry Round-Up

Fran Lock reviews some recent poetry collections

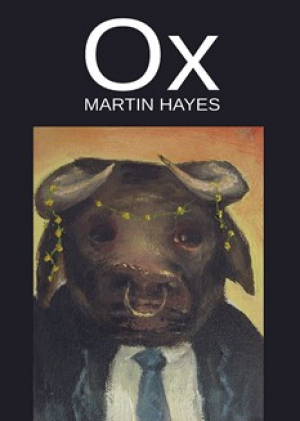

Ox, by Martin Hayes (Knives Forks And Spoons Press)

It has been written elsewhere that Ox marks something of a departure for Martin Hayes, who is perhaps best known as an outspoken poetic witness to the multiple indignities and oppressions of our cruel and increasingly unsustainable “gig economy”.

Ox has been described as an “extended metaphor” or “allegory” for the dehumanising treatment of workers under late-stage capitalism. This is true, up to a point, but when speaking about a book that has a blistering indictment of our economic system at its heart, the word “allegory” makes me a little squeamish. Certainly Ox is an allusive book, referencing prior texts, drawing on strands of myth, and working in and through the tradition of the fable. Certainly Ox is a figure for the suffering social subject within neoliberal culture. But the grim, arbitrary, and brutalising experiences that beset Ox are not allegorical. They are specific and real. They are happening now, to animals and to humans, and we lose sight of this at our peril.

It is also worth noting that this recourse to poetic conceit is, in itself, another form of tradition: in creating Ox Hayes manifests the difficulties inherent in writing about our material conditions under any aggressively surveilled system. As Fred Voss has already noted, writers who live and work within totalitarian regimes “have had to create allegories to escape detection by control-freak authorities.” Hayes’ strategy, then, is not merely a free literary “choice” but a necessary negotiation around the strictures, limits, and ugly punitive logic that govern Ox's world and his own. His innovation is driven by the social and economic forces that are his target, and this pressured invention has produced a bravura lyric performance of real wit, depth and intensity.

A particularly striking example of this is 'Ox Witnesses Yet Another Birthing' (82), a short poem worth quoting in its entirety:

here it comes the new born

with nothing in front of it

and everything behind it broken

who can predict what this fresh sun will investigate

its brightness is not for us but ours to devour

hot blood has already knitted the words of its poem

warming up not only its mother but other planets also

there is a depth to this deeper than known soil

it sits somewhere in darkness wearing darkness

we are resigned unknowing how it all works

no blueprints survive

we must go blind into the waters every time

The use of 'birthing' as opposed to 'birth' in this poem is significant: emphasising the agonising mechanics of the process (of giving birth) rather than the hallowed specialness of the end result (the baby) Hayes signals the way in which the natural reproductive cycles of both animals and humans are exploited and distorted under capitalism. Aside from the title, Hayes deliberately avoids using species-specific language, inviting a reading across both literal and figurative (human and non-human) axis; such a reading reveals subtle shifts and shades of meaning. Is the 'nothing in front' of the new-born the literal concrete wall of a leaky barn? Or is it the blank and circumscribed future of the labouring poor? Is the 'everything' that is broken behind the new-born a reference to the dilapidation of their immediate surroundings, the pre-fuckedness of the environment and society into which they are born? Or is it the physically exhausted body of its birth mother, hollowed out by hard use as a source of reproductive labour?

Without ever once using the word, the poem nevertheless merges both forms of “labour” in ways reminiscent of Ariana Reines' The Cow (Fence Books, 2006). As Reines’ text reminds us, both women and animals are similarly objectified under capitalism through the metaphor of “meat”, which allows both to be perceived as something “edible”, and ripe for different kinds of consumption. Reines' book connects the animal industrial complex to the treatment of women, exploited as mere bodies for their reproductive capacities, or for their flesh. For real-life cows and oxen, tied to the demands of both the meat and dairy industries, birth and death are hideously intertwined: male calves are born simply to be slaughtered for veal, cows are artificially inseminated and kept in a constant state of pregnancy. Often they are separated from their calves, their milk siphoned off for human consumption.

Animals are people and people are animals

This world of pain is explicit and constant throughout Hayes' collection. But Hayes also excels at the subtle and troubling lyric moment: 'there is a depth to this deeper than known soil / it sits somewhere in darkness wearing darkness', hints at a dimly perceived and not necessarily benevolent mystery behind the immediate real. Birth and death still have the power to stir and disturb. Ox cannot comprehend, but deeply feels the immensity of the 'birthing'. A sense of futile miracle hangs over the scene: I found it one of the most haunting passages in the book.

There are other “difficult” moments in Ox. As a lifelong vegan of the old school, I found some passages harder to read than others. What is both horrible and compelling about, for example, the visceral description of unblocking the “chute” in a meat-processing plant that opens 'Ox at the Gates of Heaven' (74) is not the graphic extract itself, but the way Hayes links the bland affect of the slaughterhouse worker to the genocidal consequences of human fascism globally. Each itemised part of the process of death is linked to a human tyrant, so we have 'the silver hooks of a Torquemada', 'the white ceramic guttering of a Pol Pot's throat', the 'lullabies of Marine Le Pen' in a long historical chain of oppression, dismemberment and terror.

We cannot, Hayes seems to say, separate the way we treat animals from the way we treat people. More importantly, in order to treat either animals or people with such shocking and casual violence, you first have to morally anaesthetise those who will carry out such acts. The most surprising thing about this piece, and the about the collection as a whole, is the empathy Hayes extends to the slaughterhouse workers of this world. An ambivalent empathy, perhaps, but still an important acknowledgement of our mutual exploitation.

As I read the collection I was reminded of Joan Dunayer, writing in Animal Equality: Language and Liberation (2001). Dunayer talks about the process of dehumanisation, and the inherent speciesism necessary for this process to work: to reduce the human to the level of an animal, we must first account the animal as nothing. The brutalising treatment of animals, then, is not merely cruel, but a necessary precursor to fascism, and to all kinds of human atrocity. As a culture we become accustomed to cruel acts by perpetrating them first against animals. Specisism also creates the language in which it is possible to dehumanise the “other” amongst us: the black man is a monkey, the Jew is a cockroach, the “gypsy” is a rat, etc. The figure of Ox is perhaps so unsettling because he serves as a hybrid between the animal and the human, because he demonstrates that the distance between animal and man, self and other, is not as great as some would like.

There is so much more to say to about this book: the poignancy of 'Little Ox'(85), which cuts the reader with the mediocrity of even our ambitions: 'Little Ox wanted more and more / of what he was being told / he wanted', a state of stunted imagination only possible when neoliberal elites have colonised even our imaginative space, and have naturalised their own shitty desires as the model for all aspiration. I could also talk about the eventual death and dismemberment of Ox, and the way the book takes us through his deconstruction into units of saleable product, while also showing us with an unflinching eye the impact this death has on those who cause and those who experience it.

I should also talk about the illustrations by Gustavius Payne, the softened lines of which often work provokingly against their disturbing content, or, in other places, such as 'Ox and Cow Under Moonlight' (77) or 'Little Ox' (85), catch you off guard with their tenderness and vulnerability. These pictures are an essential component of the book's relationship to fable and its implied moral lesson, accessible to children. But they also transmit their own meaning, extending and complicating the way we read Hayes’ words, not merely repeating or emphasising them.

This book is an intelligent and passionate work, the product of long experience and rigorous thought. It reveals Hayes as a exciting poet who still has more to reveal to us. If we're smart we will heed him, and follow where he leads.

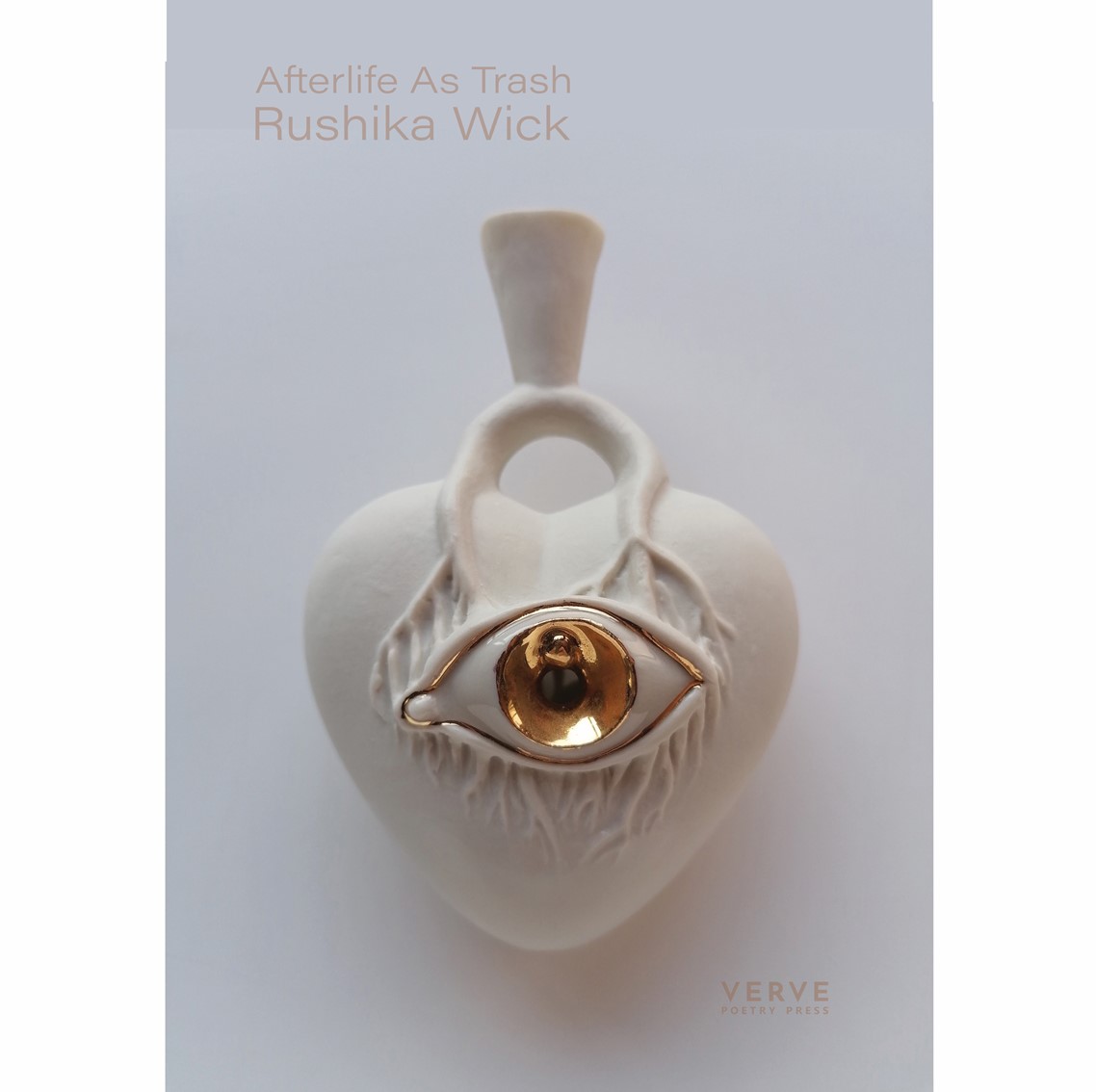

Afterlife As Trash, by Rushika Wick (Verve Poetry Press)

I must begin this review with a confession: I did not want to like Afterlife As Trash. My friends had been throwing so many superlatives at it that by the time it arrived on my desk I was quite prepared to find it overwritten / annoying / unworthy of the hype. But it isn't, not at all. As the extensive endorsements promise, it is 'pyrotechnic' and 'exhilarating' in its use of language. Wick conjures phrases that arrest and intrigue; her images, selected and choreographed with great care, are possessed of a beguiling strangeness and humour.

In the first three poems alone we find the speaker, rising above ordinary concerns, described as a 'swallow filled with helium' ('Diaries Of An Artist In Hiding', 11), sex 'like a multi-pack of Salt 'n' Shake, / each packet with its own blue sachet / containing exactly 0.6g of salt' ('ULTRAMARINE PINK PV15', 13), and sunflowers as 'velvet toys' (Deus Ex Machina', 14). Indeed, I could go through the collection happily stabbing out favourite lines and lauding their brilliance, but this would be to do Wick a disservice. This collection is far more than a trinket tray, it is probative and thoughtful too. It is also, I suspect, more political than it has been given credit for.

In 'Diaries of An Artist In Hiding', which opens the collection, the speaker conducts a 'social experiment' that sees her imaginatively incarnated as – among other things – 'the president', 'Matisse' on his sick bed, a 'love letter from Camille to Rodin', and 'a badger'. Each improbable transformation is a pleasure to read, full of the relish and the texture of language: 'flowering fingers, fractures, / scatters of light' etc. (12). It is a joy to meet with a poet so confident and accomplished in the practise of loading every rift of their subject with ore. But more than this, each leap has an aura of fugivity and flit about it; of small but necessary escapes and feints. The speaker is 'in hiding' after all; the 'experiment' takes place in 'the car / on the way to work'. These experimental selves inform a greater work of concealment and evasion, necessary to preserve whatever constitutes the artist / self from the car, and from work, and from the machine that sets cars on the road to work in the first place. 'Really', the speaker muses in the second stanza, 'the experiment is myself', and later, 'the experiment is boundless'. None of her disguises seem more essential or more “true” than any of the others. Instead, Wick seems to use them to interrogate the very notion of identity – to ask questions about how it is constituted, and more subversively, how it might be countered.

In 'Deus Ex Machina', the subject 'wonders how to make her money stretch / beyond rent and a bag of happy-face waffles', compressed like the poem's sunflowers 'in the hard corridor / between the road and tower block.' Within this space, Wick's gorgeous lyric lines function as units of resistance against the cramped precarity in which their subject is caught. The 'machine' in question is identified as an instrument of punishment or torture; it 'whirs without end' moving 'walls and ceiling' closer together like some kind of enormous trash compactor. Inside this tiny space, Wick's subject 'writes on scraps of paper as night crumples the sky', or she sleeps, having taught herself 'how to wake up just in time, / gasping'. By literalising the vague semantic gesture of 'the machine', Wick solidifies the dangerous and often fatal consequences of late-stage capitalism upon the bodies and minds subjected to its horrible logics. 'God' in the context of the poem is the just-in-time awakening the subject performs, but it is also the subject herself: a creator nevertheless condemned to exist inside the endless circuit of whirring and crushing. Here the act of writing, or the work of the imagination, is not an “escape” as such, but an act of preservation.

In 'The Party' Wick contrasts a timeless scene of exhausted and endangered solidarity with one of contemporary neoliberal privilege, so that 'To stand together, united against the dragging through fields, the hangings, the spitting on children the taking of women like property' sits uneasily beside 'It was the kind of conversation where people living in comfortable homes full of art and fruit bowls confess that the time is such that they would be able to kill their political leader, should the opportunity arise, for the greater good.' (15).

The effect is disconcerting on a number of levels. The italicised section in a which a crowd gathers 'in the burning sun, in belief' is written in the active present tense, so that the speaker is part of the moment she describes. It feels immediate and urgent. The contemporary section is written in the third person, past tense, and encodes the very kind of ironic distance that could be said to characterise its subjects. From a position of relative safety they indulge in extreme political declarations. This 'creates some solidarity at the party but also deep discomfort'.

Here the use of 'solidarity' is defanged and depoliticised: the guests at the party cannot mobilise to form any kind of meaningful dissenting collective; their gestures (that of killing their political leader) are individual, grandiose, and hollow. Wick's use of commas to break up the “confession” create qualifying or rationalising pauses within the statement itself, a syntactic signal towards a deep lack of political commitment. Because the phrase 'The Party' merges political and social worlds, the reader is invited to consider the limits and intersections of both, and the way in which the latter often usurps or comes to stand as a substitute for the former.

Witches on a field trip

In the final stanza we are told that 'Others said that finally they had been allowed the time (because of reaching a certain stability or point in their careers) to become fully practising witches and what a joy this was.' There is a wonderful piece of Wicksian strangeness here, with the “witches” organising a field-trip to Mexico to 'scrape gilt off Madonnas at night.' But behind the enjoyable oddity of this image seems to lurk a searing criticism of those who, owing to the privilege and stability of their own positions, are able to ape, participate in, and appropriate the resistive tactics of marginalised and persecuted “others”.

None of which captures the formal daring of this collection, or just how deft and supple these poems feel on the page. It is worth mentioning here that this kind of lively innovation is something that has come to characterise Verve Poetry Press, which has been steadily building a diverse stable of poetic voices, representing a wide variety of positions and approaches, publishing work by Geraldine Clarkson, Sean Wai Keung, Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, and Charlotte Lunn (collections by Golnoosh Noor and Emily Rose Galvin are eagerly anticipated).

Indeed, Verve feels like the natural home for Wick, whose engagement with the blank space of the page is mercurial, curious, and unafraid to take risks. In poems such as 'The Pill' (40), 'My Identical Twin' (48) and 'Vocal Tics' (51) Wick proves herself an adept at manipulating the kinetics of the text to achieve a number of poetic effects. These poems evince an understanding of text as substance, structure, and stuff: the shape and placement of words on the page are used to complicate or extend meaning. In 'The Pill', the left edge of the text extends outwards in a convex parabola; the right edge recedes and impresses raggedly: the poem performs the pill dissolving, or the dynamic arc of the “high”, or the retinal lens across which intoxicated images rapidly jump and flicker. On the opposite page (41), Wick lists italicised 'side effects', which include 'taking control of stress that is structural in cause'. The interaction between these two sets of text might best be seen as the relationship between our subjective bodily experience, and the external (and structural, and systemic) forces that govern that experience.

Wick's work, then, is playful but with purpose. What impresses about this collection is that it wears its obvious intelligence so lightly. The connected soliloquies from 'The Dog' (19) and 'The Flea' (20) are both witty and charming, while still pushing language and logic to strange new places. My personal favourite piece is 'THE THOUGHTS OF VALERIE SOLANAS (in the minute before shooting Warhol and the minute after)' (30). This is a deeply convincing character poem without becoming a burlesque on Solanas' signature style. Both Wick's poem and Solanas' own writing are spaces in which thinking occurs; important thoughts strained through coruscating language, full of profanity, clotted alliteration, surprising metaphor, and brute fury. Wick gives us 'the oppression of pressed paper', 'being fucked roughly / like islands in storms' and lines of heartbreak and insight such as: 'I think of what makes you a success, / and me a sideshow, an extra' and the gunshot as: 'a hysterectomy / of sorts, the language of violence / has its own vowel sounds'. Solanas under Wick's care is ranting, frustrated, but brilliant. Wick writes with both energy and empathy.

The collection is linked by a series of short italicised vignettes, which treat of ephemeral and fleeting moments. These moments work well, they introduce space into what is a rich and generous debut. They also demonstrate that Wick is not a one trick unicorn: behind the fireworks there is a poet of brevity and silence. I sense Wick may need that silence sometimes, to gather her strength for whatever comes next.

Apricot Sun, by Trisha Heaney (Culture Matters)

Trisha Heaney's impressive debut brings to fruition the mentoring package offered by the Bread and Roses Poetry Award, founded and facilitated by Culture Matters, and kindly sponsored by Unite. The package supports unpublished poets with their first collection, pairing them with an experienced editor and mentor. In the case of Apricot Sun, Heaney received mentorship from Jim Aitken, and this feels like a natural fit: both Heaney and Aitken have backgrounds in education and community outreach work, work that informs and infuses their writing. Both poets excel at the evocation of place – geographical, social, and historical – an evocation achieved through strategies both painterly and dramatic, so that the teasing appeal to the eye contained within 'mushrooms bulbing in bunches; pears fattening / like bottoms' ('Bukra Insh'allah', 53) or the wistful lyric 'Traffic lines smudge / apricot sun tones to magenta. / Soon the city's poor / will be drawn here to sleep / in the feathering of doves / paracletes of Picasso.' ('Sketch', 81), are balanced by a virtuoso conjuration of voice: 'Decantit, tene-dementit, / in a botched experiment / we pour ontae thi fields / o South Nitshill' ('In the Scheme of Things', 17).

Heaney deploys dialect and demotic throughout the collection to superb effect. Nowhere more so than in 'Ghazal, In Sudan' (21), where the Arabic verse form holds a powerful expression of loss in Scots dialect. What impresses about this poem is that Heaney does not, as so many poets do, adopt the mere shell of form; there's no awkward shoehorning of ideas and images into a container they were never designed to fit. Rather, voice and form work together to produce a layered and complex interaction between strong vocal identity and inherited poetic tradition. The different sets cultural expectations associated with the speaker's voice and the Arabic form create a fruitful friction in the text, provoking questions about what it means to mourn, and the ways in which loss is contained and transmitted through accent and grammar on one hand, and poetic structure and tradition on the other: 'Ma soul at hame in tacht alignment wae Islam / ma hert forfeit, ablo zodiac signs, in Sudan.' Heaney's love of Sudan, where she worked for a number of years training teachers to teach English, is also palpable: 'Wae ilka letter woven we're entwined, in Sudan.'

Apricot Sun reflects a broad and serious concern with voice throughout: with who is given permission and space to speak, and who is listened to. The epigraph that opens 'In the Scheme of Things', the first poem in the collection, is taken from A Social History of Glasgow Council Housing 1919-59 by Sean Damer, and tells us that the testimonies of council tenants have been 'a strategic lacuna in the history of Glasgow.' 'Strategic' is the operative word in this sentence: silence doesn't happen to people, it is done to them. Heaney keenly understands that silence, as a consequence and structural component of poverty and neglect, is a form of violence. In places this understanding is politically explicit, such as in 'Dropped' (29), 'Ria Formosa' (76), or 'As You Lie Sleeping' (33) where workers brilliantly 'shrug the shiver off / the morning / [...] carrying the world.'

In others this idea is the dark and troubling undersong beneath everyday interaction. In 'Street Theatre' (22) Heaney places a beaten and bedraggled woman at the centre of a Shakespearean sonnet. Through repeated references to stage-craft – 'alley stage', 'she might have been an actress in distress / miscast ingenue', 'set a cardboard mess', 'She stammers lines' etc. – Heaney emphasises the complicity of both the onlookers within the poem, and the poem's readers, accustomed as we are to female degradation as a staple of popular entertainment, and to the odd conjunction of aesthetic pleasure and human suffering within art and literature. The closing couplet: 'The audience directs the final act: / conduct her safely home or see her whacked?' serves to sensitise the reader ('the audience') to their responsibilities toward the suffering “other” whose safety and survival are often dependent upon the choices we make; the extent to which we are willing to acknowledge our shared humanity.

On one level this poem is an exhortation against indifference and disdain. But it is also about allowing this abjected “other” the space to speak and to be heard, even if her speech can only approximate the 'lines of threatened violence' that have been repeated 'grunted' at and into her. By using a form enshrined within canon literature, the subject is afforded both legitimacy and care. The menace of the final couplet contains also the threat of forcible eviction from the elite space of literature and the precincts of human attention.

Radical solidarity

Heaney's signature gift is this attention, and whether it is directed at her own family, or at her playground peers in South Nitshill; with exploited and exhausted workers, with prisoners, or with the victims of global misogyny, her poetic gaze illuminates whoever she holds within it. By focussing with particularity and tenderness on the lived experiences of diverse individual subjects, Heaney reveals not their differences but their (and our) deep interconnectedness. This notion of radical solidarity feels authentic and inhabited within Heaney's work because her own experiences inform and intertwine with her writing about others. There is a great sense of vulnerability and risk within these poems, which form a rich seam of lyric memoir. This poetic vulnerability and exposure is not merely the “price of admission” for collecting the experiences and testimonies of others, but a metonym for the vulnerability that besets all women, but especially poor and working-class women inside neoliberal culture.

Vulnerability is one of Heaney's most persuasive themes: workers are vulnerable in literal and bodily ways, as in 'Sweat Shop Sojourn' (27), where blades 'chop down' and a machine operator may go 'in fear of losing fingers or / a red right hand'. Wives are physically vulnerable to husbands, as in 'Christmas Spread' (70), where a man brutalised by work (or lack or work) and drink, metes out violence to the woman in his life. Women are vulnerable everywhere: to men with power, to those without any real power and angry about it; to the endless arbitrary cruelty of the law, as in both 'Dirty Linen' (47) and 'Vale of Tears' (63), where intimate violence is compounded at institutional and structural levels, further victimising those the law purports to help.

An experience of poverty leaves you emotionally vulnerable too; this may be our greatest risk and biggest strength. It is certainly a strength within Heaney's writing, where empathy and compassion combine with real technical gift to create a compelling and inspiring debut.

Crucifox, by Geraldine Clarkson (Verve Poetry Press)

It feels unjust to describe Crucifox as “slight”, although at a mere 37 pages, it is certainly brief. It is not, however, an inconsequential collection, and each individual poem is possessed of Clarkson's trademark riddling intricacy and zinging lyric flair. Where else could we expect to encounter lines of such audacity and flourish as 'glimquist and sunkissed on a burgandy chaise lounge / she turns phrase after phrase on the lathe of her tongue' ('lemonjim hour: brittle england', 24)? Or 'consonants mimicking kisses', 'myrrh mired-in-my-memory, passing gold' ('Labials of a Half-Remembered Lover', 30)? Signals of excess, indulgence, and abundance are shot through this collection like lamé thread. Although Clarkson's poetry is always linguistically rich, Crucifox feels pleasurably super-saturated. This is Clarkson with the dials turned up to 11.

The collection seems to mark a point of departure or change for Clarkson, and the opening poem, 'Janus' (7) feels like an apologia or manifesto of sorts for the unrepentant lavishness that is to follow. The speaker in 'Janus', having endured: 'a hateful hagiography of dragging winters / with incipient springs, word-ugly / and black-fasted, on the poorer side / of my life' assures us that 'now the worm was feeding / at the lintel, ready to rear up.' The use of 'hagiography' and 'fasted' are significant here: containment, enclosure, and worldly withdrawal– especially as these apply to religious life – were the signal preoccupations of Clarkson's previous collection, Monica's Overcoat of Flesh (Nine Arches Press, 2020). Although Monica's Overcoat of Flesh featured moments of flat-out fugivity and freedom, the poems and their speakers felt continually caught in a compromise between restraint and flight: raw lexical energy imperfectly held within the strictures of form. It gave the poems a restless, edgy quality, while in Crucifox that energy is a allowed to surge forth with strange new vigour.

Throughout the collection there are numerous instances of escape, revolt, or turn. Not merely within the lives and psyches of Clarkson's individual poetic subjects, but within the order of commonplace logic itself. In 'THE BOOK OF BLUE' (31), a monk 'glad from Nocturns', succumbs to the urge to illuminate a 'slippery and impure' (“blue” in the sense of “profane”) manuscript, 'extemporising nipples, buttocks, quim' at the stroke of a quill. While 'Apple Snow' (12) and 'FILTH' (17) are marked by moments of overrun and ruction in the fabric of daily life.

Pert mounds of blancmange

In 'Apple Snow' the speaker is gifted a 'big-chinned baby', left on the doorstep by her neighbour, my Grandet. After 'much shuffling of official forms' the speaker is informed that 'the girl' who grows prodigiously and quickly, 'will live with me, hereafter'. An illogical sequence of events the counter-spell to which is an equally illogical (poetic) solution. The situation rights itself in the following not, not in resisting the surreal surrender of sense, but in committing to it:

'she occupies herself in compiling an index of domestic magic, and will answer to the ancient English name Wigga. In return for board and lodgings she will source a daily breakfast of fruit, variously foraged and prepared: whiskey-poached pears, plum fritters; devilled figs, pert mounds of blancmange topped with apple snow'.

In 'FILTH' the chaos consumes an unwary emissary of the outside (rational) world. The 'mult' in 'Bella Langley's' closed-up home multiplies while the 'deranged house' urges the man inside and swallows him. No sign for ten days until 'the sirens, the lights. / A blue suit stained.' There is ambivalence here, and threat, reactivating and filling with ominous portent the dead cliché of “behind closed doors.” As Clarkson writes, the collection traffics in 'female desire and feral impulses behind polite exteriors […] the silent and marginalised aspects of women, their masking and unveiling...'

Crucifox, then, is a place of power, but not necessarily a benevolent power. Within its pages flowers and cats speak, and booksellers offer vials of glowing emerald liquid, as in 'Compliments of the Patron' (25). Indeed, enchantments are continually proffered throughout Crucifox, but to enter the space the poems extend with safety one must be canny, fleet, and well-armed with sympathetic magic of one's own, with the 'informal cunning' of Fox in 'FOX NEWS: CREATRIX' (20) perhaps? Clarkson presents this poem as a series of crossword clues. The answers appearing on the opposite page in 'CROSSFOX: CROSSBOX' (21), are all variations on, or sound or sense components of, the word 'crucifox'. Because there is no such word, the ability to 'solve' the puzzle is a tantalising promise without hope of fulfilment. Meaning is illusive or labyrinthine. Here Clarkson is telling us something about language and its dangerous, mercurial potency; its ability to both bind and release us, to liberate or frustrate; to create or destroy.

In 'St Osburga's Surprise' (26), a nun is vouchsafed a vision of the future, and wonders 'Was this destruction or resurrection? Conventrated / re-created'. The same might be asked of Crucifox, and the answer is probably “both”. In the three felicities (36), which closes the collection, Clarkson ends with her subjects 'wreathed impossibly in sudden / lucky smiles, now self-assured and utterly reliable'. Does this poem signal that the charm is at an end? Are we released back into the 'reliable' world which has resumed its usual contours around us? Or is there an implied wink within that line? 'Crucifox is more a state of mind than a particular creature or person', writes Clarkson; having stepped once in Crucifox that state of mind stays with you.

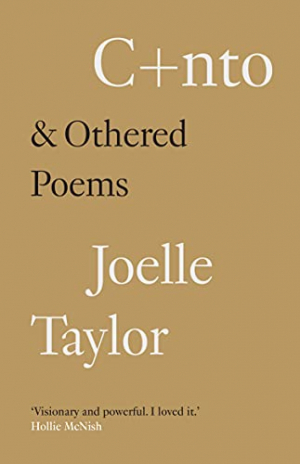

C+nto & Othered poems, by Joelle Taylor (Westbourne Press)

Although in June it seems early to start talking about The Most Important Single-Author Poetry Collection of the Year, and despite having already reviewed C+nto in depth, I still want to cheer this book here as a strong contender for that title.

C+nto is the culmination of both patient and difficult (in every sense) research, and years of working and reworking the white-hot stuff of the poem through the pressure of performance. Discussions of Taylor's work often describe her as a compelling “spoken word” or “performance poet”, and while this is undoubtedly true, such descriptions tend to elide Taylor's vigour and innovation within the body of the printed text. I do not use the word “body” idly.

A protean and charismatic reader of her own work, Joelle Taylor's poetry is embodied to a high degree; the intimate tactility of performance is a vital element of relish and risk within her work. The body is also Taylor's most vivid subject, specifically the bodies of those whose histories, political destinies, safety and survival are tied to their physical identity: women, and butch lesbian women in particular are variously fetishized, debased, erased, and destroyed by the social and economic systems that govern them. Taylor's texts seem to store the scars of this accumulated bodily experience; standing for the living bodies whose integrity is violated by various kinds of violence.

In Taylor's 2017 collection Songs My Enemy Taught Me, she uses a mixture of oral testimony, found text, and personal experience to bear witness to the trauma of her own sexual abuse, but also to confront the chronic and ongoing sexual exploitation of women world-wide. A similar dynamics of archivism, excavation, and witnessing takes place within C+nto, which is a work of memoir, of fearsome imaginative and creative reach, and of deep historicity. Taylor undertakes this work with love, dexterity, and wit.

You're visible in all the wrong ways

C+nto begins by providing a definition for the title, and its Latin root in the verb 'Cuntare', to narrate, or to recount. Taylor also provides a glossary of words from wildly different lexes: from the coterie argot of LGBT+ occulture, through scientific, legal, and cinematic terminology, to Taylor's own invented slang. Juxtaposing this concern with the origins and precise meanings of words, Taylor frame the poems in highly visual ways, deploying the trappings of cinematography or stage direction to create their 'scenes'. In the preface to the poems Taylor describes the central conceit of the collection in the following way:

Glass display cases appear across the UK outside the old bars, cruising grounds, and squats that once held the LGBT+ community in parenthesis. […] Each case holds a different scene (13)

These cases are a metaphor for the moments in which LGBT+ history is experienced and communicated. Erased, repressed, redacted, it becomes impossible to identify oneself within any coherent system of “belonging”. The glass offers brittle and ultimately doomed protection for the exposed subject while simultaneously trapping her. This is the contradiction at the heart of being a butch lesbian: you are missing within official history; you are excised from cultural representation even within LGBT+ cohorts, and yet you are visible in all the wrong ways: an obtruding target for ridicule and violence, a medical curiosity, and a sideshow spectacle. Your visibility is politicised and policed. You are dangerously visible, rarely seen.

Against this willed lack of perception, Taylor creates C+nto with a lyric and militant tenderness. The language with which Taylor holds her subjects performs an elegiac cherishing. In Dudizile, who: '...speaks difficult / rivers knowing too / many bois are lost / in them those rip / tides of sudden belief / the undercurrent of/ language she speaks...' (87) Taylor's poem catches the cadence of thought and tongue particular to her subject. The richness and originality of Taylor's lyric phrase-making gives these figures substance and voice. C+nto understands that the most we can offer the dead is our unstinting vigilance, our attentive and loving witness.

C+nto is also an elegy for place. Not some twee nostalgia for a vanished / imagined past, but a work of grieving, a lament. The Maryville scenes are amongst the most ambitious and exciting within in the collection, offering up an incandescent melancholic 'psalm'; both an evocation and an invocation, a spell:

o, Maryville / let us walk alone at night / & let the night not follow us / let us drink too much / & awaken in each other's mouth / o Maryville / let us be ugly / let us unwash / let us language... (55)

C+nto seeks to create the very spaces that it mourns: however hedged, however temporary. The gold cover glows like a beacon of hope, a hope undermined, at least complicated, by the redacted 'u' of the title. The offence contained within the word 'c+nt' becomes metonymic for the “offensive” and unwanted presence of Taylor's lyric subjects.

Joy is abundant in C+nto: a hard-won joy that knows itself to be fleeting. Throughout, there is a sense of 'bursting' into existence, but that moment never arrives, is never allowed to coalesce and form enduring destinies. As the rainbow signifiers of “pride” are adopted by neoliberalism as a hollow consumer brand, these truth feel especially necessary. In 'Eulogy' Taylor presents a litany of names compressed into stark columns, barely contained within the form of the text (113). This is the multitude that C+nto carries. These are the book's grieved-for subjects, and its truest audience. These are the voices that need to be heard, and that we need to hear.

The Brown Envelope Book (Caparison, with Don't Go Breaking Our Arts and Culture Matters, 2021), edited by Alan Morrison and Kate Jay-R.

A brief disclaimer: because I have work in The Brown Envelope Book I wasn't initially sure if I should write about it or not. It gave me pause, but in the end I have decided that this book is so much bigger and more important than any one contributor. And “should” is a funny word in this context. Are the niceties of writerly “ethics” really more important than maintaining the visibility of a book so rare in its creative energy, and so profound in its political implications? I do not think so.

The Brown Envelope Book collects poetry and prose on contributors' varied (but always harrowing) experiences of unemployment, of the benefits system, and of disability and work capability assessments. The poems were selected and edited by Alan Morrison and Kate Jay-R, and the anthology features an important contextualising Foreword by John McArdle of the Black Triangle Campaign, established in 2011 to advocate for the human rights of sick and disabled people persecuted by the government's work capability assessments scheme.

Thinking about what makes this book so timely and so striking, it occurs to me that we inhabit a cultural moment where literature and the arts are deeply preoccupied with “identity”. Within such a moment it is often the case that the signifiers of identity – working-class identity in particular – are adopted, co-opted, and assimilated by the culture machine, while the social and material contexts under which that identity is forged, and under which our art is made, are wilfully vanished. The Brown Envelope Book feels significant for the way in which it triangulates artistic expression, social experience, and the ideological underpinnings that create and contour that experience. A number of publications deal thematically with “austerity” or “poverty” but by engaging with a specific piece of state apparatus, The Brown Envelope Book renders explicit the malignant functioning and human cost of this Tory government's political agenda against working-class, poor, and vulnerable people.

The title evokes the ominous “Brown Envelope” that brings with it news of sanctions, delays and denials of help, worked out according to some arbitrary and inhuman logic, and relayed in correspondingly inhuman language. When I use the word “inhuman”, I mean that quite literally. Many of the poems in The Brown Envelope Book incorporate fragments of this found text, which feels appropriate, as if, in their awkward construction, their evasive and affectless tone, these phrases have proved indigestible to even the most adroit lyric facility.

Forms must be brought in person

This is captured most starkly and completely in Angi Holden's 'Dear Client' (171), which reproduces the content of a DWP communication in the form of a poem, and in doing so demonstrates the impossibility of artistic recuperation for such a document. The content of the letter confounds the lyric reading expectations of intimacy and catharsis that are encoded within the shape and structure of the poem; the disorientation this produces is chilling.

Elsewhere, the language of these letters is burlesqued and satirised, as in Penny Blackburn's 'Jumping Through Hoops' (98) or Joel Schueler's 'Questions of Validation' (276). I will not say that Blackburn and Schueler exactly “exaggerate” the inherent absurdity of this language, rather they use bleak humour to make both the violence and the Kafkaesque illogic of the letters readily legible. Blackburn does this in subtle shifts and accretions, showing us that absolute nonsense is an ever-present prospect, a question of degrees: 'Each significant piece of information / must be accurately placed / within the correct, identified box / of the specified form — / available Wednesdays, bi-weekly, / when the moon reaches the nadir. // Forms must be brought in person / to our top floor office (no lift) / 3 miles from the nearest road or rail link, / open every 5th Friday (mornings only)...”

Schueler takes a more direct approach, stating nakedly the bigotry and threat contained within these communications sotto (but only just) voce: 'Dear sponger, / No parachute will be necessary. / Move away from the funds / without as much as a day to prepare / for your nothingness.'

Another striking feature of the anthology is the sheer number of times the letters themselves are referred to or described. They initiate or punctuate the poems, breaching and disrupting lyric space; they interrupt, command and coerce. As physical artefacts they have an almost totemic potency. This potency is figured most hauntingly in Rachel Burns' 'We do not know when normal service will resume' (113): 'and the letter unfolded itself like a broken wing / the wrong kind of origami'. The letter 'unfolded itself', it is not inanimate, it has agency and momentum. It is 'the wrong kind' of origami, a malevolent magic, bad juju.

These envelopes are metonymic for and de facto extensions of the brutalising state; they condense the power of that state into one easily recognised symbol (the brown envelope), so that the symbol itself transmits that power and the fear it provokes. The hateful presence of these letters in the lives and homes of vulnerable people serves as a form of remote terror, a kind of distance-bullying. This metaphor is captured beautifully by Fiona Sinclair in 'Fear of Letterboxes' (284): 'Sundays, strikes and snow, she is a school kid / whose bully has been excluded for a few days.' Anyone who has known bullying will understand this feeling: the giddy bitter joy of brief respite; the horrible uncertainty as to when your torment will resume.

Epistolarity itself carries connotations of intimacy; the very act of being addressed, and the spectre of implied response invoked by address render the recipients of letters uniquely vulnerable. When governments and state institutions address their citizen-subjects through letters they mobilize epistolary rhetoric in a variety of ways: to compel the individual and command the public; to coerce cooperation and engineer consent. The dreaded brown envelope is a particular kind of epistolary communication: it speaks not to us, but at us, with an intrusive and imperative address that demands response but denies our right to meaningful reply. Our subordinate and dependent position is inscribed not only through the language of that address, but through its very presentation. The brown envelope itself silences us.

We're vital, alive and as mad as hell

The Brown Envelope Book creates against this silence a space of reply. In subverting the signifiers of the brown envelope – the cover is designed to mimic the appearance of a DWP communication, the font and typesetting have the look of “official” letters – the anthology attempts to return some of our accumulated fear and distress to sender. By allowing the recipients of those envelopes an opportunity we were never afforded as citizens and subjects, the anthology forms a powerful work of testimony, it gives us back the nuance and complexity of embodied experience, a complexity shaved out of tick-box bureaucracy, and the deliberately limiting anti-language of assessment criteria.

This is invaluable to those whose experience of the world and of themselves has been reduced by such criteria. Reading The Brown Envelope Book I was deeply moved by the depths of creativity, the intellectual rigour, and the artistic dedication of my fellow contributors. This anthology is proof that we make, in our different ways, a valuable contribution to our communities and culture; it is proof that we know how to spin nectar out of shit. The Brown Envelope Book never allows that nectar to provide a tacit justification for the shit either. Rather, it begs the question: what might we create or accomplish if our government allowed us to be seen as human beings? In this way our art is not merely cathartic or therapeutic solace but a manner of critique, a way of holding power to account. This comes across clearly in Clare Saponia's poem, 'The importance of being an artist' (275): 'That voice shrieking: / “You’re a slacker” / IS NOT YOURS! / It’s the rage / of the system / slamming its doors. / It’s the whip / of red tape / that doesn’t want you to feel. / It’s the guilt / in your bones / that work doesn’t heal.'

The anthology also provides a way of mediating these varied experiences to the wider (especially political) world, and of beginning to unpick the damage caused by decades of misrepresentation and barefaced lying about who and what we are. Many of the poems answer and challenge these misrepresentations directly, as when Maria Gornell, in 'In Sickness and In Wealth' (152) writes 'because you can’t be sick / and clever at the same time / send me more brown letters / to reinforce my absolute / uselessness on earth.'

These poems prove that perception a lie. We are vital and alive, and as mad as hell.