Marvel's Loki

Reece Goscinski reviews Loki through a Zizekian lens

Loki is the latest entry in the canon of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), streaming as a TV series on Disney+. The serial takes place around the midpoint of 2019’s Avengers: Endgame and sees the Nordic God of mischief (Tom Hiddleston) flashing through various timelines as he discovers the nature of reality within the MCU. After being arrested by the Time Variance Authority – which exists outside time and space – he is eventually recruited to help fix and stabilise the flow of time. On his journey he meets multiple Loki doppelgangers from across various multiverses. Eventually he falls in love with a female version of himself (Sophia Di Martino) who wishes to expose the truth of reality in the MCU.

Whilst watching this series I could not help but be reminded of many key points and concepts created by the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Žižek is a controversial figure combining elements of Hegelian philosophy, Lacanian psychoanalysis, and Marxism to analyse our contemporary ideological positioning. The majority of his writings as well as his two documentaries Perverts Guide to Cinema (2009) and Perverts Guide to Ideology (2012), see Žižek analyse modern cinema to extract understandings of our contemporary ideology. For Žižek, understanding popular films and popular culture is vital to understanding our present situation (what are our values? what is the meaning of life? etc.)

Drawing upon Lacan’s concept of the falsifying ego, Žižek is coming from the assumption that our identities and daily functioning are constructed by mimicking images outside of ourselves. For Lacan, humans are always alienated from ourselves as we are constructed by continuously copying the images and actions of others. The ego, in a Freudian sense, then convinces the subject that they are whole and coherent when in fact they are not – the real body is fragmented. For Žižek then, this is precisely why the images of cinema are so important to understanding contemporary societies and ourselves. Borrowing from Marx, his adaptation of the concept ideology to not only describe a false consciousness but the actions we conduct knowing they are not real has been influential. Cinema therefore presents us with an ideological understanding of ourselves which we then construct to suit the system.

Given the MCU is one of the most successful franchises of the past decade (with a total worldwide box office of $22.5 billion), the films must say something about our current ideological state, based on Žižek’s logic. So I thought it might be an interesting idea to analyse Loki (2021) using a Žižekian methodology. By doing this I hope it will encourage further reading and engagement with his work as well as provide a unique perspective of the MCU.

Disney’s Liberal Propaganda?

Over the last decade Disney has come under criticism from elements of its fanbase for adopting a “politically correct agenda.” Across its content and theme parks the company has aimed to diversify its output through positive representations of peoples and inclusive filmmaking. Films such as Moana (2016), Black Panther (2018), and Star Wars (2015 – present) have been praised for these changes by the liberal press. Conservative fans on the other hand have seen it as the imposition of a political agenda in place of a story with Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson calling Frozen (2013) propaganda.

Despite Disney’s reputation as a Social Justice Warrior by the right, Loki’s narrative remains conventionally conservative. Within the story, it is revealed that many years ago the MCU timeline was unified by three mysterious beings known as the Timekeepers to prevent war in the multiverse and create stability. This resulted in the “proper flow” and harmony of time which is overseen and maintained by the Kafkaesque Time Variance Authority (TVA). As the narrative continues, it is revealed that every action conducted by individuals within the MCU is predetermined and manipulated by the TVA and Timekeepers. This realisation motivates the character Sylvie (female Loki, Sophia Di Martino) to expose this truth to obtain free will for all. Slowly it is revealed that the Timekeepers are little more than masks for an entity known as He Who Remains (speculated to be Immortus from the comics). He Who Remains has unified the timeline and removed free will to prevent the timeline falling into chaos and an evil version of himself controlling reality.

The conservative underpinnings of the story lay in British philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes’ understanding that our pure state of nature was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” describes the period before He Who Remains unified the timeline. As equal factions compete for dominance over the acquisition of resources and life preservation, the situation evolves into a “war of all against all.” In the face of this, the rule of law and a common power are needed to bring order to the situation. Relating this to the series, He Who Remains and the TVA portray themselves as necessary to counter desires of free will and truth sought by Sylvie.

In the final episode, He Who Remains explains that whilst his actions may be considered unethical it had to be done to prevent a multiverse war. This again is a nod to the British utilitarian thinker Jeremy Bentham. For He Who Remains this was the best option to maximise the utility of the multiverse. The ethical dilemma now faced by Sylvie on her quest for freedom is to either accept the dominance of the timelord and forgo her free will; embrace the impeding fragmentary multiversal chaos; or exchange this utilitarian God for a multiversal totalitarian despot.

Applying our Žižekian methodology to this part of the narrative we are confronted with an insight to our time. Žižek argues that ideology is a social fantasy structuring reality against the Lacanian Real. The Real for Lacan is that which has not been symbolised or in other words the trauma of a meaningless void which has not been articulated through language. It is this understanding of the Real that allows Žižek to argue that all reality must contain fantasy in order for it to function.

In the series, we can take the utilitarian version of He Who Remains as a symbolisation of the post-Cold War New World Order (the Blair/Clinton/Bush/Cameron/Obama brand of neoliberalism and global interventionism). This system created an ideological social fantasy of harmonious markets, entrepreneurial self-interest, and claims of being the rational option to construct our reality. In the same way, the utilitarian God of the series makes similar claims of being the rational choice to justify his shaping of reality. With many financial commentators declaring an end to neoliberalism back in 2016, concerns have been raised over international populism, the rise of China, and questions as to what will fill the ideological void. Anxieties emerging from the collapse of the symbolic order feel ever present within the popular mindset.

In Loki, Sylvie’s decision to slay the utilitarian mirrors the popular dissatisfaction with neoliberalism and anxieties presented by this opening. Once the utilitarian is killed with no one to take his place, the traumatic chaos of the Real ensues through the collapsing of reality. By the end of the series the void is filled by the despotic God who has reorganised the symbolic order towards authoritarian ends. The message here not only stokes fears of the CCCP and right-wing populism, but advocates the maintenance of the status quo as our youthful revolutionary demands for freedom hide totalitarian results.

The TVA and Ideology

One of the more interesting elements of the series comes in the form of the TVA. The TVA is a bureaucratic organisation created by He Who Remains to oversee the proper functioning of time. In Stalinist fashion and decor, any member of the multiverse who breaks the proper flow of time is summoned before judge Ravona Renslayer (Gugu Mbatha-Raw) and “pruned” to re-establish the correct timeline. When Loki is sent here at the beginning of the series for “crimes against the sacred timeline” he must pass through a series of bureaucratic checkpoints including confirmations of his identity, tickets to confirm his place in line, and the signing of papers confirming “everything he’s ever said.”

Soviet inspiration

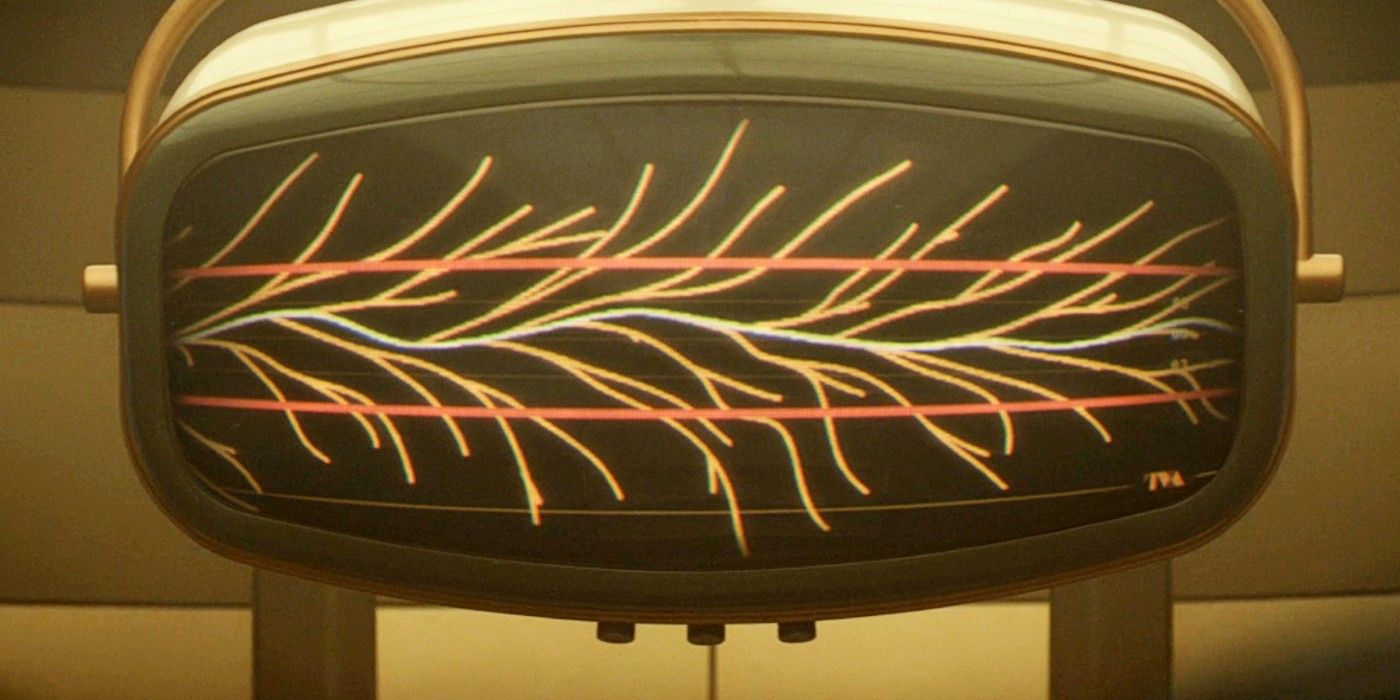

Whilst the satire of the situation is not lost – the contradiction of a Nordic God in a mundane everyday encounter – the design of the TVA further reflect Western anxieties of China in its mise en scene. Soviet inspired artwork, 80s inspired television screens, and beige and brown colour schemes decorate the offices of the TVA as if lifted from a reconstruction of Stasi offices. As the main plot is a conflict between Sylvie’s affirmation of free will (Western democracy) against the TVA’s autocracy (Xi Jinping), the political undertones of the narrative are clear from the onset.

The Kafkaesque nature of the TVA also lends itself to an exploration of bureaucratisation under neoliberalism and Žižek’s understanding of ideology. According to Žižek, ideology functions not through obedience to conviction and understanding but through belief and a lack of understanding. In the bureaucratisation of our everyday lives (see Graeber) this form of ideological construction becomes more important.

TVA Office

In episode two there is a conversation between Loki and Mobius (the TVA agent played by Own Wilson). Within the scene, Loki mocks Mobus’s belief in the Timekeepers and in response makes the remarks “I don’t get hung up on this ‘believe and not believe.’ I just accept what is”, “existence is chaos. Nothing makes sense and I’m just trying to make sense of it”, and “it’s real because I believe its real.” These quotes reflect the functioning of ideology and the ideological state apparatus according to Žižek. For Mobius, there is a chance that the TVA, the Timekeepers, and his purpose may not be true but he continues to act as if it is true to preserve his social reality. This again is a reflection on the functioning of bureaucracies in our world. The aim is not to understand its workings but to merely believe that it is functioning for good to uphold the fantasy of capitalist order.

The idea of ideology as a belief is seen most radically in episode three when Loki explains to Mobius that he is a brainwashed variant kidnapped from a timeline by the Timekeepers. His initial response is to laugh and deny it to sustain his ideological fantasy. The most radical objection to this truth is then displayed by Judge Renslayer. In episode four when Mobius starts to believe Loki and aims to convince Renslayer of this truth, Renslayer reacts violently to uphold the TVA and prunes Mobius despite their relationship in the series. Within her reaction to Mobius, we can see that she is aware of the knowledge Mobius has given her but still aims to maintain her social fantasy. This is not to uphold her ideological purity but to sustain her social reality.

Both of these extreme reactions convey the day-to-day functioning of ideology. On some level, we gain satisfaction from our ideological symptoms and will do anything we can to maintain them. It is only through a personal desire to overcome our symptoms that we can take on the dominant ideology. This is the challenge presented to the viewer in response to the cosmic opening played out in Sylvie’s story. By Sylvie ridding herself of the dominant ideology and killing the utopian God her naive quest for freedom has resulted in totalitarianism. This story again reinforcing the maintenance of the status quo by upholding ideology.

Marvel’s Loki is timely entry into the MCU canon with echoes of Western Cold War era programming. Using our Žižekian methodology, the series exposes present political anxieties, expressions of our ideological condition, and Western fears of China. The popularity of the MCU is likely to continue reinforcing our ideological symptoms and uphold the dominant conservative worldview. Nonetheless we should become critically aware of these underlying meanings and challenge its conservatism.