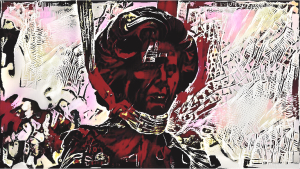

'Bondage' and 'Captivity': Two poems by Dan Melling, introduced by Fran Lock

Introduction by Fran Lock

Please read the poems below. In Bondage we enter a scene reminiscent of agrarian indentured labour, somewhere (to my mind anyway) in the long Middle Ages. But as the poem progresses, we come to realise that the bond the subject owes is not only to labour, lord or master, but to the land itself, and through the land, to the future. It could be set anywhere at any time. While the work is difficult, there is both an intimate and inevitable quality to the paces Melling's labourer-subject is put through. At the end of the piece we might find ourselves reflecting on the precise degree of difference between responsibility and debt, between being tied and being bound.

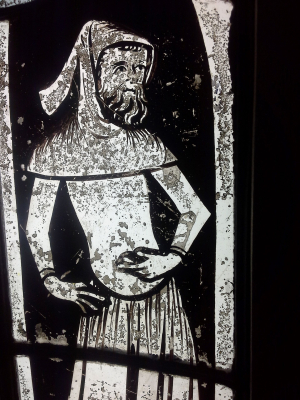

I knew I wanted to write something about this poem the moment I read it, because it conjured for me such a clear and specific image. In the Stained Glass Museum at Ely Cathedral there is a 14th century fragment, formerly part of the decorated canopy in the Lady Chapel. It depicts a small (gaunt) peasant figure in tunic and cowl hood - see image above. Such figures were rarely depicted in medieval art, so it's incredibly striking. The figure's arms are bent, his left on his hip or the small of his back, while the right is strumming his thin belly like a ukulele. There's no translating the look on his face, but to me it seems purposeful, grim; the mouth is set in an unsmiling line. I've seen men come off night shift looking like that. I read stiffness in his posture; he's awkward in the way he holds himself as if trying to negotiate the discomfort of his own body. Or it's like he knows he doesn't quite belong in the chapel; can't decide how to stand or where to look. I thought of him vividly when reading this poem.

It's not just the scene the poem evokes, but there's something about Melling's choice of short, thin, interconnected tercets that helps to irresistibly recall that figure. The rhythm these stanzas inscribe is not that of the mellifluous, contemplative lyric line; this is not a poem of ease, in breath or in body. Instead, the poem is patterned in quick, syllabically irregular bursts. It doesn't 'flow', it halts and starts; effort is written into the structural stuff of it. And yet, because of the way each stanza bleeds into the next, the piece has its own inexorable momentum. Melling achieves this momentum though minimal use of punctuation, but also through deft attention to sound, using the sonic properties of words to create chains of meaning across lines and between stanzas, for example 'matters', 'scrabbling', 'hand' and 'land' weaving, in sonic counterpoint, to 'leak', 'tears', 'feet', and 'sweetens'. These sound-chains serve to unite the human body with the body of the land, not only through cycles of physical exertion, but also through dissolution and decay. We fertilise the land, but we are also the fertiliser. Our bodies work the land, but our inescapable destiny is that the land will one day go to work on our bodies.

Class, place, art and labour

Marxist critic William Empson, writing in Some Versions of Pastoral (1935), suggests that 'good proletarian art is usually Covert Pastoral.' By which he means that from Thyrsis on, pastoral poetry has used the scene of nature as a site and occasion for talking about the pleasures of art and the difficulties of work, to that extent that pastoral poems often contain disguised commentaries about the tense interrelations of class and place; art and labour. One of the things I love about this poem is that it makes the interrelation of these forces explicit. It also, I think, gives the lie to a big inherited hangover from the Romantic lyric tradition, where N/nature is a democratically accessible psychic resource, one that we exist apart from, but which we can tap for either inspiration or consolation as the mood takes us.

There's no dualism in this poem: we 'scrabble', 'leak', and 'sweat' into the earth; the earth 'leeches' into us. That sonic affinity between 'leaking' and 'leeching' is a particularly deft touch, emphasising how these twin processes mirror each other in continuous cycles. There is also the reference to 'bulbs and pulses' in the sixth stanza: 'pulses' clearly refers to the edible seed of the legume plant referenced in the previous stanza, but it also carries connotations of human heartbeat and breath; the human body is also full of bulbs. They are both literally and figuratively 'of us'. Everything about the poem signals a tactile enmeshment with the natural world.

Something else I found myself fascinated by was the strategic repetition of 'matter'. This feels significant, and it had me thinking about the various meanings and definitions of 'matter': as an elementary physical substance distinct from the world of spirit and thought, and as a subject under consideration. 'Matter' might also be used to refer to print materials, summoning the scene of writing. Again, the poem speaks back to the long shadow cast by Cartesian dualism: matter and spirit are not distinct categories at all, just as the scene of writing or thinking and the scene of nature are not distinct; one provokes, sustains and shapes the other. Bondage may in fact refer to our inescapably earthly (and earthy) embodied existence. Acknowledging this shifts our perceptions of nature, but it also challenges some pretty embedded assumptions about who has access to – for want of a better phrase – the life of the mind, and the places where meaningful consideration can be found.

A profound note of ecological and social hope

Given all this, what are we to make of the poem's ending? The first time I read it I saw the (false) comfort of a promised hereafter, either in terms of religious eternity or the capitalist fantasy of working yourself to death to better the lives of your children. Both could be seen as consoling fictions, weaponised by regimes of power to forestall meaningful action towards change in the present. In which case 'Bondage' might also stand for the human mind in thrall to such palliative and politically suspect illusions. But then I read it again: far from deferred gratification producing a state of suspended animation, the poet's subject is incredibly purposeful and active. What they seem to have realised is that they are working towards change so glacial as to be virtually imperceptible within the span of an individual life. They are part of a generational process, incremental, accumulative, and steady.

While the idea that the next life, or the next life will be better could be seem as ultimately futile wishful thinking; a self-soothing mantra that allows the subject to endure the unendurable, it could also signal an allegiance to the slow work of change. I'm reminded of the oft-quoted maxim of Bobby Sands that “Our revenge will be the laughter of our children”. For the subject this futurity 'is enough'. Perhaps this poem is set in that future, a signpost to the slog ahead if we are to save even a portion of our burning earth. In affirming an arduous commitment to that E/earth and to life, the poem sounds a profound note of ecological and social hope.

I wanted to look at Captivity alongside Bondage because it has such a radically different setting and tone, yet it is also concerned with different kinds of imprisonment, confinement, responsibility and powerlessness. While neither piece is morally didactic or instructional, placing these two poems side by side did make me think of Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience, in that they explore contrasting states of the human soul, extrapolating outwards from individual spiritual or mental conditions to the social conditions they engender. I found this a really useful way to think about both texts.

The first thing that struck me about Captivity was its use of open and connected couplets: each brief stanza is a vivid, self-contained moment that jumps rather than spills into the next. One of the things I find both interesting and impressive about this poem is the way in which Melling uses the same minimal punctuation as he does in Bondage to achieve a range starkly different expressive effects. While the tercets in Bondage blur and merge, the couplets in Captivity seem to glitch and skitter, evoking both our inundated and distracted attention, and the escalating assault on senses and spirit so common to the Western world. Both poems use their structural properties to create momentum, but while Bondage uses the line to build pace with purpose by inevitable increments, Captivity inscribes what Rachel Blau Duplessis has called the “malignant rapidity” of contemporary capitalism: a space in which we can briefly witness, but rarely reflect on the conditions and experiences that beset us.

The very opening line of the poem moves us out of an implied reflective space: 'I’ve been spending too much/ time looking through stained/ glass.' We might think immediately of time spent in ecclesiastical buildings, or perhaps of some cloistered scholarly space with its connotations of ivory tower insularity. We're left to guess what the speaker means by 'too much' or by what metric, because the thought itself is interrupted by reported speech, words that seem equally to puncture the space of the poem, coming from the outside in: 'Friend' says the voice, an appeal that quickly transforms into an accusation: 'that’s not even/ enough for a cup of coffee, friend.'

This is the speaker's first moment of failure; the first time they find the gestures they are able to make unequal to the suffering they meet with. In this context 'Friend' takes on a bitterly ironising quality. We might imagine that the homeless figure uttering those words is inflecting them with a certain degree of sarcasm, but the idea of friendship and the bonds of human care are themselves being scrutinised within the poem as it sensitises us to the gap between a form of words and their meaning. This becomes more apparent as the speaker moves inside, where a nameless institutional 'they' 'lock me into another/ shift.' The carceral, almost involuntary quality of 'locked' feels significant here, as the speaker enters a territory where the work of care is securitised, privatised, and coerced into pre-determined shapes. Yet 'shift' may also be meaningful: a period of labour, but also a change, perhaps of perception. Does working within this institution demand a new or unnatural way of seeing; one that the speaker must train or force themselves to inhabit?

From the third to the seventh stanza the speaker is again confronted with their powerlessness in the face of human suffering by 'a woman –/ trafficked – shared with us/ no common language' as she 'danced sadly lifted her shirt/ white pulse of fear/ & impotent energy'. Here the 'no common language' is not merely the lack of a mutual mother tongue, but something within her experience of suffering that exceeded or was failed by language itself. The woman is compelled/ reduced to dancing, to gesture because her experience is in a sense unspeakable. There is also the sense, I think, that her gestures are uncommon as in rare; they provoke a profound response that is, in itself beyond the speaker's power to fully articulate. The syntax of the poem allows the present of the speaker and the past of the dancer to collapse into one another. 'there was no help/ that could happen' for her during the event or after; the 'white pulse of fear/ & impotent energy' could belong, syntactically, to either speaker or subject equally. The use of the ampersand in place of the more usual 'and' serves further to compress and contract the moment, to collide identities and temporalities.

And then with a snap, the poem is back for a brief moment in a contemplative place, thinking with some regret about the well-trodden philosophical standard of Plato's cave analogy (very basically, that for figures chained in a cave only aware of shadows on the wall, the shadows would appear as absolute reality; any prisoner forcibly removed from their cave would experience pain and violent terror before slowly adjusting to the world beyond, while others would resist leaving the relative safety of the cave at all). The speaker states that 'the sad thing about' Plato's allegory is 'how obsessed we've always been with captivity/ a maggot born of a human brain/ hatched in tradition.' These are lines of unusual power: the sonic affinity between 'captivity', 'maggot', 'hatched', and 'tradition' create a chain of association that relates the idea of imprisonment to that of sickness, degeneration, madness and decay, and decay to traditions of thought in which captivity is a dominating metaphor or concern. Underpinned by allegories of imprisonment, our 'traditions' themselves create prisons of thought, reproducing the captive conditions they seek to describe.

It's a peculiar segue, and rendered all the more unsettling for being so vitriolic and so brief. Again, this feels entirely deliberate: the poem refusing to conform to our notions of a contemplative lyric space. Instead it spurs us on, back into obtruding reality, all simmering violence and off-kilter menace: 'a man with half a nose/ demonstrates on his hand how to bite/ off a nose.' These last five stanzas proliferate images of prisons: even the off-licence is behind a security cage and reinforced glass; hypersexualised and exploited women are pictured 'writhing in white cubes', and these women are themselves compared to a memory of arctic foxes in a bare and dismal zoo. The idea of captivity is itself inescapable, no matter what the speaker tries: alcohol, crack, pornography, sleep. His imagination turns in tight cycles. Carceral saturation has rendered the prison pervasive and invisible. We have ambient prison now, there are no other terms of reference.

This is not a hopeful poem, but neither is it hopeless. I think, rather, it is about hopelessness; about the patterns and traps we are conditioned to fall into. It is chilling, but I kind of think we need it.

Bondage

by Dan Melling

Most mornings

he thinks what

matters if

we spend our lives

scrabbling in dirt

really it’s quite intimate

the intimacy between hand

and hoe, between land

and the fertiliser we leak

onto it, the mud

churned with tears and feet

the sweat that evaporates

into rain, sweetens

in the ground

grows leguminous.

It doesn’t matter

he thinks that these

bulbs and pulses

aren’t for us

they’re of us

and that’s enough

for the days when

there’s wood to crackle

in the fire

and even when there’s

not and the ice leeches

up our legs into our skulls

at least life will be better

in the next life

or the next life.

Captivity

by Dan Melling

I’ve been spending too much

time looking through stained

glass. Friend, says the man

in the doorway, that’s not even

enough for a cup of coffee, friend.

I ring the buzzer & they

lock me into another

shift. On another shift a woman –

trafficked – shared with us

no common language

danced sadly lifted her shirt

white pulse of fear

& impotent energy

there was no help

that could happen when

they put her into the black

BMW & took her back to –

the sad thing about

the allegory of the cave is how obsessed

we’ve always been with captivity

a maggot born of a human brain

hatched into tradition. In the 24 hour

off-licence on Duke Street

with its cages & 2 inch thick

glass a man with half a nose

demonstrates on his hand how to bite

off a nose. Smoking crack with T

watching hours of Babecast

the women writhing in their

white cubes mouthing silently

into microphones, made me think

about a zoo I thought I saw

2 arctic foxes in a glass cube

with nothing but a gray blanket

& 2 small piles of shit.

Dan Melling is a writer from Skegness. He holds an MFA in poetry from Virginia Tech University and teaches creative writing at John Moores University, Liverpool where he is also studying for a PhD. His work has appeared in The Rialto, X-R-A-Y, HAD and others. He co-edits Damnation literary journal and sometimes tweets at @melling_dan.