Public service broadcasting vs. competitive capitalist profit-making: the crisis at RTÉ

The current implosion at RTÉ is not merely a short-term issue of corporate governance and public accountability. Its provenance goes a long way back in the history of the organisation and extends beyond the current spectacle of executives and board scrabbling for plausible deniability. It raises fundamental questions about the kind of public service broadcaster RTÉ should and could become.

One historical precedent to this argument began in 1968, a mere eight years after the station was founded. Three senior producers—Jack Dowling, Lelia Doolan and Bob Quinn—resigned very publicly, declaring that “RTÉ had an inadequate idea of itself” and publishing the book Sit Down and Be Counted. There was a Late Late Show discussion about the issues but their arguments about the danger of ignoring new technologies, of stifling creative freedoms and adopting a more progressive direction were quickly defused and discounted.

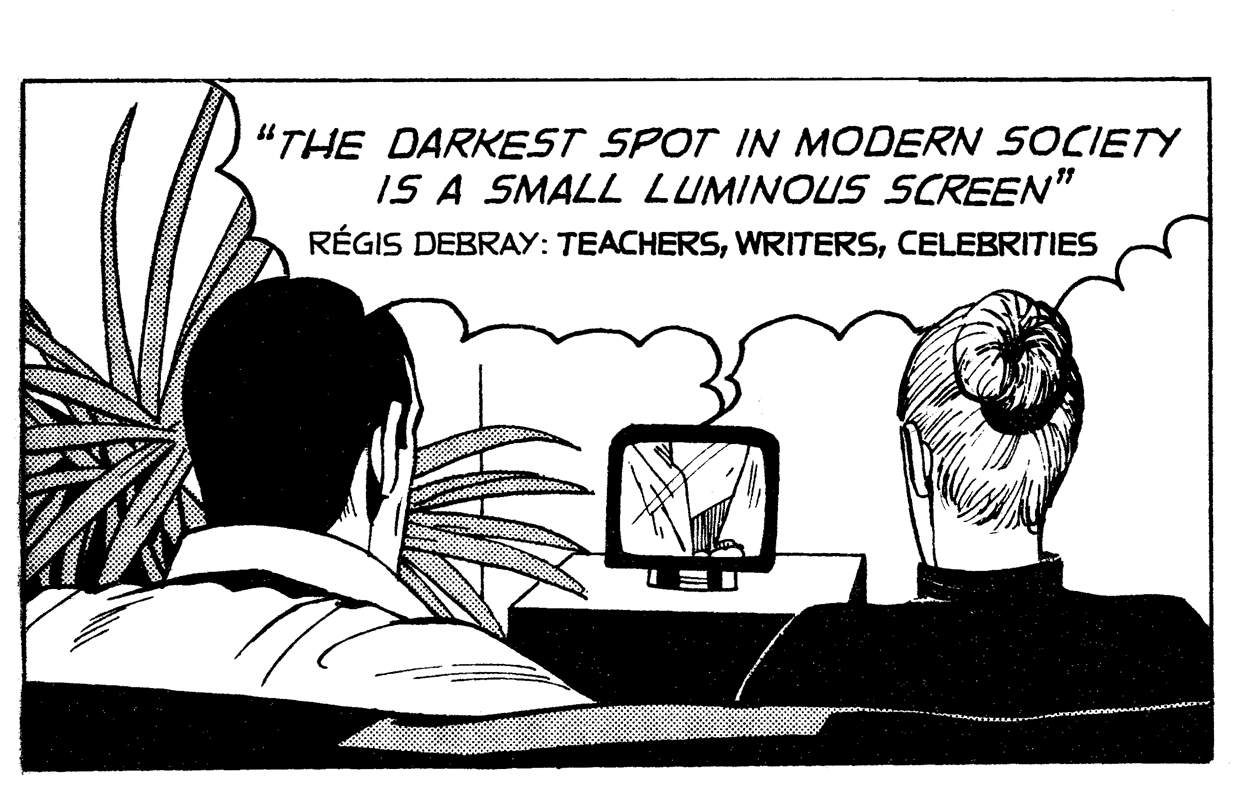

The last few decades have witnessed an overall decline in public service broadcasting in Europe as many national television and radio stations have been drawn inexorably into competing with commercial models. In the early 1980s, the three RAI stations in Italy found their audience slipping with the onslaught of Silvio Berlusconi’s private channels. There were fierce debates inside the state broadcaster as Berlusconi’s Mediaset captured more than 50% of the television audience. Many argued in favour of replicating commercial formulas – “If you can’t beat them join them”, while others suggested that “We should define our differences as a public service more strongly, and practice them”.

The launch of Channel 4 in the UK in 1982 brought significant change as the concept of a mass audience was discarded in favour of an address to smaller and more specific niche audiences. As the country’s first “publisher broadcaster” it was programmed with imagination and commitment, bringing genuine diversity to the anachronistic and calcified structures of British television. The political and cultural context for the new station was set by legislation to “innovate in the form and content of programmes”, and a remit “to reach new audiences not catered for elsewhere”. Although the context of its intervention has changed entirely, and cannot be replicated in some nostalgic way, the principles of reinvention, embracing innovation and risk-taking could point to a new path for RTÉ.

Fighting powerful commercial sectors on their own terrain and competing head to head with their formulaic programmes, repetitive formats dominated by over-paid star presenters has been a strategy for failure. Explaining that this is delivering “what the public want” is not an adequate argument then or now: the free market is not democratic or an index of taste, rather it is a mechanism fulfilling desires that it has itself manufactured.

Creating cultural democracy in TV programming

Living in this time of rapid transition to a digital world it is imperative to rethink and reinvent RTÉ’s editorial approach as well as creating a more transparent, democratic economy for the national public service broadcaster. Linear television viewing has already been discarded by a younger generation and is fading fast for the rest of us. Migrating to the streaming model, we are coming to terms with life-changing technology. George Boole, the 19th century Cork mathematician, has a lot to answer for— he was responsible for the algebra behind the algorithms that now curate our taste and predicate our choices.

Clearly some elements from the traditional linear viewing will persist in new hybrid digital television and some programmes, such as news, sporting events and live music will continue to be transmitted at a fixed time. However, other diverse material, from short pieces linked via social media and YouTube to new drama and documentary series will be marketed to be viewed at our convenience.

A different identity for RTÉ can emerge from rethinking the principles of public service broadcasting on this contemporary basis. Rather than imitating programming based on delivering an audience to advertisers, television and radio can develop new approaches that reinvent national broadcasting in its most dynamic dimensions. TG4 is an example of what a certain level of protection from commercial forces can achieve in terms of intelligent and high-quality documentary-making and award-winning features.

Commitment to innovation and risk-taking would create a space where a new generation of Irish programme-makers can refresh the airwaves editorially and aesthetically. A younger generation is already reimagining versions of arts and politics on social media—Whispers News, Dust to Digital, Novara Media— exploring the meaning of quality and excellence in unexpected ways.

People Make Television, a recent exhibition at Raven Row in London, laid out the pioneering work of the BBC Community Programmes Unit in the 1970s; wide-ranging programmes made by myriad groups and perspectives. Channel 4’s network of regional workshops followed, exploring different forms of access. Democratic and accountable media is also a guarantor of independence from government pressure or interference. Part of the focus should be serving young people and minority groups’ self-representation within film and television. A wider spectrum of political pluralism is necessary to open debates about the urgent issues facing the country at this time.

New technologies for recording sound and images allow direct speech in the public domain on an instantaneous basis. Communities of interest and the sounds of life from cities and villages around the country have the potential to shift the balance to participatory access and interactivity by minimising the processes of mediation. Public service broadcasting is not to be confined to the serious and the slow. Engaging with audiences will release the creativity in most people. A brief glance at Instagram and Tik Tok shows that original talent for filmmaking is out there, it’s just not evenly marketed or distributed to a wider public.

This is not a matter of rebuilding anachronistic structures with a greater emphasis on integrity and public accountability. RTÉ needs to be independent of commercial pressures through a new funding model which would also secure its long-term future in an era when television advertising revenue is in decline. Now is the time for RTÉ to undertake a fundamental reimagining of its public service mission in the digital era and to escape the commercial competitive sphere which is at the root of many of its current woes.