Megan Behrent considers what we can learn from the great strides made in education in revolutionary Russia.

"All Russia was learning to read, and reading - politics, economics, history - because the people wanted to know. . . . In every city, in most towns, along the Front, each political faction had its newspaper - sometimes several. Hundreds of thousands of pamphlets were distributed by thousands of organisations, and poured into the armies, the villages, the factories, the streets. The thirst for education, so long thwarted, burst with the Revolution into a frenzy of expression. From Smolny Institute alone, the first six months, went out every day tons, car-loads, train-loads of literature, saturating the land. Russia absorbed reading matter like hot sand drinks water, insatiable. And it was not fables, falsified history, diluted religion, and the cheap fiction that corrupts—but social and economic theories, philosophy, the works of Tolstoy, Gogol, and Gorky." John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World

There is no greater school than a revolution. It is therefore not surprising that some of the most innovative, radical, and successful literacy campaigns are those that are born out of revolutions - when, on a mass scale, people fight for a better society. In revolutionary periods, ideas matter as never before, and literacy needs no motivation as it becomes a truly liberatory endeavor. Thus, from the trenches of the US Civil War and the Russian front to the battle lines of El Salvador, there are innumerable stories of soldiers teaching each other to read newspapers in the midst of war and famine. One of the most inspiring examples of the revolutionary transformation of literacy and education is the Russian Revolution of 1917.

The Russian Revolution was a watershed historical moment. That workers and peasants were able to overthrow tsarism and create a new society based on workers’ power was an inspiration to millions of oppressed and exploited people around the world. At the time of the revolution, the vast majority of Russians were peasants toiling under the yoke of big landowners and eking out a meager existence. More than 60 percent of the population was illiterate. At the same time, however, Russia was home to some of the largest and most advanced factories in the world, with a highly concentrated working class. By October 1917, the Bolshevik Party had won the support of the majority of workers and established political rule based on a system of soviets, or councils, of workers, peasants, and soldiers.

The revolution itself, occurring in two major stages in February and October, took place in conditions of extreme scarcity. In addition to the long-standing privation of Russia’s peasants, the First World War caused further food shortages and disease. No sooner had the revolution succeeded than the young Soviet government was forced to fight on two military fronts: a civil war against the old powers just overthrown, and a battle against some dozen countries that sent their troops to defeat the revolution. As the Bolsheviks had long argued, the longevity and success of the Russian revolution depended in large part on the spread of revolution to advanced capitalist countries, in particular to Germany. Despite five years of revolutionary upheaval in Germany, the revolution there failed. The young revolutionary society was thus left isolated and under attack.

Despite these conditions, however, the Russian Revolution led not only to a radical transformation of school itself but also of the way people conceived of learning and the relationship between cognition and language. Indeed, the early years of the Russian Revolution offer stunning examples of what education looked like in a society in which working-class people democratically made decisions and organized society in their own interest. In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, education was massively overhauled with a tenfold increase in the expenditure on popular education. Free and universal access to education was mandated for all children from the ages of three to sixteen years old, and the number of schools at least doubled within the first two years of the revolution. Coeducation was immediately implemented as a means of combating sex discrimination, and for the first time schools were created for students with learning and other disabilities.

Developing mass literacy was seen as crucial to the success of the revolution. Lenin argued: “As long as there is such a thing in the country as illiteracy it is hard to talk about political education.” As a result, and despite the grim conditions, literacy campaigns were launched nationally among toddlers, soldiers, adolescents, workers, and peasants. The same was true of universal education. The Bolsheviks understood that the guarantee of free, public education was essential both to the education of a new generation of workers who would be prepared to run society in their own interests and as a means of freeing women from the drudgery of housework. Thus, there were attempts to provide universal crèches and preschools.

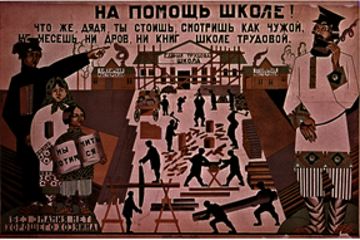

What the October Revolution gave to the female worker and peasant, 1920 Soviet propaganda poster. (The inscriptions on the buildings read "library", "kindergarten", "school for grown-ups", etc.)

None of these initiatives was easy to accomplish given the economic conditions surrounding the young revolution. Victor Serge, a journalist and anarchist who later joined the Russian Communist Party, describes the staggering odds facing educators and miserable conditions that existed in the wake of the civil war: “Hungry children in rags would gather in winter-time around a small stove planted in the middle of the classroom, whose furniture often went for fuel to give some tiny relief from the freezing cold; they had one pencil between four of them and their schoolmistress was hungry.” One historian describes the level of scarcity: “In 1920 Narkompros [the People’s Commissariat for Education] received the following six-month allotment: one pencil per sixty pupils; one pen per twenty-two pupils; one notebook for every two pupils…. One village found a supply of wrappers for caramel candies and expropriated them for writing paper for the local school.” (Ben Eklof, Russian Literacy Campaigns,1861–1939 in Robert F. Arnove and Harvey J. Graff, eds., National Literacy Campaigns and Movements: Historical and Comparative Perspectives)The situation was so dire that “in 1921, the literacy Cheka prepared a brochure for short-term literacy courses including a chapter entitled ‘How to get by without paper, pencils, or pens." Nonetheless, as Serge explains, “in spite of this grotesque misery, a prodigious impulse was given to public education. Such a thirst for knowledge sprang up all over the country that new schools, adult courses, universities and Workers’ Faculties were formed everywhere.” (Victor Serge, Year One)

Historian Lisa Kirschenbaum describes the incredible gap between the conditions imposed by famine and what kindergartens were able to accomplish. On the one hand, these schools had to provide food each day for students and teachers in the midst of a famine simply to prevent starvation. And yet, as Kirschenbaum writes, “even with these constraints, local administrations managed to set up some institutions. In 1918, Moscow guberniia [province] led the way with twenty-three kindergartens, eight day cares (ochagi) and thirteen summer playgrounds. A year later it boasted a total of 279 institutions…. Petrograd had no preschool department in 1918, but a year later it reported 106 institutions in the city and 180 in the guberniia outside the city. Other areas reported slower, but still remarkable, increases.” (Lisa A. Kirschenbaum, Small Comrades: Revolutionizing Childhood in Soviet Russia, 1917–1932)

Within these preschools, teachers experimented with radical pedagogy, particularly the notion of “free upbringing,” as “teachers insisted that freedom in the classroom was part and parcel of the Revolution’s transformation of social life.” Kirschenbaum elaborates: “By allowing, as one teacher expressed it, the ‘free development of [children’s] inherent capabilities and developing independence, creative initiative, and social feeling,’ svobodnoe vospitanie [free upbringing] played a ‘very important role in the construction of a new life.’”

A central aspect of expanding literacy in revolutionary Russia was deciding in which language, or languages, literacy should be developed. Before the revolution, tsarist colonialism had forged a multinational empire in which ethnic Russians comprised only 43 percent of the population. A central political question for the Bolsheviks—the majority of whom were Russian - was how to combat the legacy of Russian chauvinism while also winning non-Russian nationalities to the project of the revolution. A full discussion of this history is beyond the scope of this chapter. But it is important to underscore how progressive Bolshevik politics were with respect to native language education.

Already in October 1918, the general policy was established to provide for native language education in any school where twenty-five or more pupils in each age group spoke the same language. Implementing the policy depended on a number of factors. For example, within Russia proper, where some national minorities such as Ukrainians and Byelorussians were already assimilated, few native-language programs were set up. Within Ukraine itself, however, the extent of native-language education was reflected in the rapid demand for Ukrainian language teachers and Ukrainian-language textbooks in the years following the revolution.

Nativizing language and literacy education for populations in the Caucasus and Central Asian regions of the old empire was a more complicated task. In part, the difficulty stemmed from efforts under tsarism to use differences in dialect to divide native peoples in these regions. In addition, in some cases the languages most widely spoken had not yet developed a writing system. Thus, part of nativizing education meant deciding which language should be used in school, and which system (for example, Cyrillic, Roman, or Arabic script, or something different altogether) should be used to write it. Despite these practical challenges, native language education became the rule rather than the exception. Again, a key indication is the number of languages in which textbooks were published, which grew from twenty-five in 1924 to thirty-four in 1925 to forty-four in 1927. As British socialist Dave Crouch summarizes: “By 1927 native language education for national minorities outside their own republic or region was widespread, while in their own republic it was almost total.” (Dave Crouch, “The Seeds of National Liberation”, International Socialism Journal 94)

At the same time universities were opened up to workers as preliminary exams were abolished to allow them to attend lectures. The lectures themselves were free, art was made public, and the number of libraries was dramatically increased. There was an incredible hunger for learning in a society in which people were making democratic decisions about their lives and their society. One writer describes: “One course, for example, is attended by a thousand men in spite of the appalling cold of the lecture rooms. The hands of the science professors . . . are frostbitten from touching the icy metal of their instruments during demonstrations.”

A whole new educational system was created in which traditional education was thrown out and new, innovative techniques were implemented that emphasized self-activity, collectivism, and choice, and that drew on students’ prior experience, knowledge, and interaction with the real world. Anna-Louise Strong, an American journalist who traveled extensively in Russia after the revolution, wrote about her experiences and recounts a conversation with one teacher:

“We call it the Work School,” said a teacher to me. “We base all study on the child’s play and his relation to productive work. We begin with the life around him. How do the people in the village get their living? What do they produce? What tools do they use to produce it? Do they eat it all or exchange some of it? For what do they exchange it? What are horses and their use to man? What are pigs and what makes them fat? What are families and how do they support each other, and what is a village that organizes and cares for the families?”

“This is interesting nature study and sociology,” I replied, “but how do you teach mathematics?” He looked at me in surprise.

“By real problems about real situations,” he answered. “Can we use a textbook in which a lord has ten thousand rubles and puts five thousand out at interest and the children are asked what his profit is? The old mathematics is full of problems the children never see now, of situations and money values which no longer exist, of transactions which we do not wish to encourage. Also it was always purely formal, divorced from existence.

We have simple problems in addition, to find out how many cows there are in the village, by adding the number in each family. Simple problems of division of food, to know how much the village can export. Problems of proportion,—if our village has three hundred families and the next has one thousand, how many red soldiers must each give to the army, how many delegates is each entitled to in the township soviet? The older children work out the food-tax for their families; that really begins to interest the parents in our schools.” (Anna-Louise Strong, The First Time in History)

Within schools, student governments were set up - even at the elementary school level - in which elected student representatives worked with teachers and other school workers to run the schools. In so doing, schools became places where students learned “collective action” and began to put the principles of the revolution in practice. As Strong described: “We have our self-governed school community, in which teachers, children and janitors all have equal voice. It decides everything, what shall be done with the school funds, what shall be planted in the school garden, what shall be taught. If the children decide against some necessary subject, it is the teacher’s job to show them through their play and life together that the subject is needed.”

She continues by describing a school for orphans and homeless children where basic needs such as food, clothing, and hygiene had to be met before any real learning could begin. Additionally, the students spoke more than a dozen different dialects, making the shared development of a common language one of the school’s first goals. But, as the writer describes, “those were famine conditions. Yet the children in this school, just learning to speak to each other, had their School Council for self-government which received a gift of chocolate I sent them, duly electing a representative to come and get it and furnishing her with proper papers of authorization. They divided the chocolate fairly.”

A more skeptical writer, William Chamberlin, a journalist with the Christian Science Monitor who passed on information to US intelligence, described a school in which students in the higher grades “receive tasks in each subject, requiring from a week to a month for completion. They are then left free to carry out these tasks as they see fit.” (William Henry Chamberlin, “The Revolution in Education and Culture” in Soviet Russia: A Living Record and a History). He continued:

"Visiting a school where this system was in operation I found the pupils at work in various classrooms, studying and writing out their problems in composition, algebra, and elemental chemistry. Sometimes the teacher was in the room, sometimes not, but the students were left almost entirely to their own resources. The teacher seemed to function largely in an advisory capacity, giving help only when asked. If the students preferred talk or games to study, the teacher usually overlooked it. Each student was free to choose the subject or subjects on which he would work on any particular day.

This absence of external restriction is a very marked characteristic of the Soviet school. The maintenance of discipline is in the hands of organizations elected by the students themselves, and while one seldom witnesses actual rowdyism in the classroom, one is also unlikely to find the strict order that usually prevails in the schools of other countries."

Chamberlin questioned Lunacharsky, the commissar for education, about whether such a model provided sufficient education in basic skills such as grammar and spelling. Lunacharsky replied: “Frankly, we don’t attach so much importance to the formal school discipline of reading and writing and spelling as to the development of the child’s mind and personality. Once a pupil begins to think for himself he will master such tools of formal knowledge as he may need. And if he doesn’t learn to think for himself no amount of correctly added sums or correctly spelled words will do him much good.” But, Chamberlin explained, it was hard to provide hard data on the success of the program, as “marks are proverbially an unreliable gauge of students’ ability; and Russia has no grading system.” Examinations were also largely abolished, including those that had previously been necessary to gain entrance into institutions of higher education. Why? Because “it was believed that no one would willingly listen to lectures that were of no use to him.”

Anatoly Lunacharsky

The revolution inspired a wide range of innovative thinkers in education and psychology. Lev Vygotsky, known as the “Mozart of psychology,” created a legacy of influential work in child and adolescent psychology and cognition, despite being stymied and all but silenced under Stalinism. He began with a Marxist method and analyzed the way in which social relations are at the heart of children’s learning process. He wrote that he intended to develop a new scientific psychology not by quoting Marxist texts but rather “having learned the whole of Marx’s method” and applying it to the study of consciousness and culture, using psychology as his tool of investigation.

Vygotsky used this method to investigate the creation of “higher mental processes,” as opposed to more “natural” mental functions, which are biologically endowed. These higher mental processes are mediated by human-made psychological tools (for example, language), and include voluntary attention, active perception, and intentional memory. He also traced the dialectical development and interaction of thought and language, which results in the internalization of language, verbalized thought, and conceptual thinking. He argued that mental development is a sociohistorical process both for the human species and for individuals as they develop, becoming “humanized” from birth. Personality begins forming at birth in a dialectical manner, with the child an active agent in appropriating elements from her environment (not always consciously) in line with her internal psychological structure and unique individual social activity. For Vygotsky, education plays a decisive role in “not only the development of the individual’s potential, but in the expression and growth of the human culture from which man springs,” and which is transmitted to succeeding generations.

Through applied research in interdisciplinary educational psychology, Vygotsky developed concepts such as the zone of proximal development, in which joint social activity and instruction “marches ahead of development and leads it; it must be aimed not so much at the ripe as the ripening functions.” (L. S. Vygotsky, Thought and Language) This view clashed with Piaget’s insistence on the necessity of passively waiting for a level of biological and developmental maturity prior to instruction. Vygotsky devoted himself to the education of mentally and physically handicapped children; he founded and directed the Institute for the Study of Handicapped Children, which focused on the social development of higher mental processes among children with disabilities. He also discovered characteristics of “preconceptual” forms of thinking associated with schizophrenia and other psychopathologies.

Vygotsky saw as the historical task of his time the creation of an integrated scientific psychology on a dialectical, material, historical foundation that would help the practical transformation of society. As he argued, “it is practice which poses the tasks and is the supreme judge of theory.” Although this task was incomplete upon his death, and both his work and the revolution itself were derailed by Stalinism (his work was banned under Stalin for twenty years after his death), he made great headway in this process, and laid a foundation for others who have been inspired to further elaborate upon and develop his ideas.

The immense poverty and scarcity of material resources after the Russian Revolution and the subsequent Stalinist counterrevolution distorted the revolutionary promise of education reform in the early years. Nonetheless, the Russian Revolution provides important examples of the possibilities for the creativity and radical reform that could be unleashed by revolutionary transformation of society at large - even amid the worst conditions.

While the adult literacy campaign’s accomplishments were thus limited, and much of the data is hotly contested as a result of Stalinist distortions, it had important successes. In its first year of existence, the campaign reached five million people, “about half of whom learned to read and write.” While literacy statistics are hard to find, it is worth noting that the number of rural mailboxes increased from 2,800 in 1913 to 64,000 in 1926 as newspaper subscriptions and the exchange of written communications substantially increased—a notable corollary of increased literacy. In unions, literacy programs were quite successful. To give one example, a campaign among railway workers led to a 99 percent literacy rate by 1924. Similarly, in the Red Army, where literacy and education were deemed crucial to ensure that soldiers were politically engaged with its project, illiteracy rates decreased from 50 percent to only 14 percent three years later, and 8 percent one year after that. On its seventh anniversary, the army achieved a 100 percent literacy rate, an immense accomplishment, even if short-lived, as new conscripts made continual education necessary.

Perhaps more important than any of the data, however, are the plethora of stories of innovation and radically restructured ideas of schooling, teaching, and learning as students at all levels took control of their own learning, imbued with a thirst for knowledge in a world which was theirs to create and run in their own interests.

Conclusion

The complete transformation of education and literacy during the Russian Revolution exposes the lies at the heart of American education - that competition drives innovation, that punishments and rewards are the only motivations for learning, and that schools are the great levelers that provide every child with an equal opportunity to succeed.

If we have anything to learn from the revolutionary literacy campaigns of Russia, it is that genuine learning triumphs in revolutionary situations that provide people with real opportunities for collective and cooperative inquiry and research; that literacy is always political; and that radical pedagogy is most successful when it actively engages people in the transformation of their own worlds - not simply in the world of ideas, but by transforming the material conditions in which reading, writing, and learning take place. Compare that to rote memorization of disconnected bits of information, bubble tests, and scripted, skill-based curricula that suck the love of learning out of children in our schools.

Radical educators should draw on these lessons wherever possible to fight for an educational system that is liberatory rather than stultifying, sees students as thinkers and actors rather than empty containers to be filled, and recognizes that collaboration and collective action are far more useful for our students than individualism and meritocracy.

But for most teachers, the opportunities to implement the lessons of these struggles are extremely limited as curricula are standardized and stripped of any political meaning, testing triumphs over critical thinking, and our jobs are increasingly contingent on how much “value” we’ve added to a test score.

It is no coincidence that the best examples of radical pedagogy come from revolutionary periods of struggle, as newly radicalized students and teachers put forward new visions of education and reshape pedagogy. As teachers, we know that students can’t just ignore the many inequalities they face outside of the school building and overcome these through acts of sheer will. Genuine literacy that emphasizes critical thinking, political consciousness, and self-emancipation cannot happen in a vacuum. The creation of a liberatory pedagogy and literacy goes hand in hand with the self-emancipation of working people through revolutionary transformations of society as a whole.

Under capitalism, education will always be a means of maintaining class divisions rather than eradicating them. To imagine an educational system that is truly liberatory, we need to talk about fighting for a different kind of society - a socialist society in which, as Marx described, “the free development of each is the precondition for the free development of all.” It is only by transforming our society to eradicate poverty, prisons, oppression, and exploitation in all its forms that we can fully unleash human potential and creativity.

Imagine a society in which teachers and students democratically decided what learning should look like and where learning was freed from the confines of a classroom. Imagine what true lifelong learning could look like in a world in which we were free to develop our own courses of study and unlock the creative potential of humanity. If we can learn anything from the history of education and literacy, it is that such a revolutionary transformation of society is both possible and urgently needed.

This article first appeared in Issue #82 of International Socialist Review (ISR Issue #82) and is an excerpt from the chapter “Literacy and Revolution” in the new Haymarket book, Education and Capitalism.