Secrets, crimes and the schooling of the ruling class: how British boarding school stories betrayed their audience

Nicholas Tucker asks why authors of children's stories about boarding schools chose to concentrate on escapist fantasy, rather than telling the truth

Asked by a magazine in 1956 what he considered the chief characteristics of children’s literature, the veteran French writer Marcel Aymé replied ‘La bêtise, le mensonge, l’hypocrisie.’ This severe judgement ignored newer generations of European and American children’s writers who were already starting to produce works far removed from any residual stupidity, lying or hypocrisy. But in one respect he remained spot on. British boys’ boarding school stories during the whole of the twentieth century consistently chose amiable fantasy over anything occasionally getting closer to some uncomfortable truths.

With the exception of Harry Potter, British fiction set in boarding schools hardly exists today, with most contemporary writers choosing day state schools as backgrounds for their characters. But for many years before, boarding school stories were hugely popular, even appearing in comic strip. Although adult autobiography often painted a very different picture of such schools in real life, in fiction there seemed no time for raising any awkward questions. Small children reading such rose-tinted stories before attending such establishments themselves had no way of knowing whether they accurately described these places, inaccessible for all except those who went to them.

Illustration of the cruel treatment of the pupils inside Dotheboys Hall by 'Phiz', from the 1839 edition of Charles Dickens's The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby.

British girls’ boarding schools at their most traditional are largely remembered today with that mixture of affection and wry humour found to perfection in Ysenda Maxtone-Graham’s recent study, Terms and Conditions; Life in Girls’ Boarding Schools, 1939-1979. But the image of past boys’ boarding schools is now more troubling. Numbers of these schools have now been revealed as hunting grounds for predatory paedophiles, and former pupils have also written about other forms of cruelty and deprivation. Dickens’ attack on corrupt Yorkshire boarding schools in Nicholas Nickleby led to the destruction of that particular, infamous industry. But there has been no twentieth century British novelist since, writing for children or adults, who has got anywhere near taking on, let alone campaigning against, the worst features of some of the boarding schools of their own time.

More honesty can be found in nineteenth century texts. Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s Schooldays, published in 1856-7, is cheerfully frank about the darker sides of boarding school education. As his father warns young Tom before sending him off to Rugby, ‘You’ll see a great many cruel blackguard things done, and hear a deal of foul, bad talk.’ He was not wrong. Seventeen-year old Flashman and his bullying friends there ‘missed no opportunity of torturing in private.’ This is no exaggeration; Tom faints and for a moment is actually thought to be dead after being ‘roasted’ over a fire for refusing to sell his lottery ticket for the Derby races. Later on, after a half an hour bare-knuckle fight with the larger and stronger ‘Slogger’ Williams, Tom’s life is again despaired of by his sensitive young friend George Arthur, who finally manages to bring the increasingly brutal encounter to an end.

Hughes adored Rugby and its ever-manly ethos, writing enthusiastically ‘After all, what would life be like without fighting, I should like to know…the real highest, honestest business of every son of man.’ But at least prospective parents, with sons like little George Arthur who are neither strong nor war-like, are being given fair warning here of what they might have to expect. Hughes even manages to smuggle in an oblique warning about sexual abuse between boys, a topic normally totally passed over in school stories then and since. Describing one pupil, he writes ‘He was one of the miserable little pretty white-handed, curly-headed boys, petted and pampered by some of the big fellows, who wrote their verses for them, taught them to drink and use bad language, and did all they could to spoil them for everything in this world and the next.’

But that was not all. In the only footnote to the novel he adds, ‘A kind and wise critic, an old Rugbeian, notes here in the margin: ‘The small friend system was not so utterly bad from 1841-1847.’ Before that, too, there were many noble friendships between big and little boys; but I can’t strike out the passage. Many boys will know why it is left in.’ Once again, parents beware, particularly if they have a sweet-natured but delicate son and prospective pupil like George Arthur, always as Tom puts it in danger of being called ‘Molly, or Jenny, or some derogatory feminine nickname.’ Not every such pupil could rely on the protection afforded to his younger friend throughout the story by stout-hearted Tom.

Rudyard Kipling’s Stalky & Co, written 43 years later, is equally frank about the existence and occasional excesses of persistent bullying. Kindly Reverend John, the school chaplain, warns young Stalky and his two study companions Beetle and M’Turk of a ‘little chap’ who is currently being ‘hammered till he’s nearly an idiot.’ Beetle himself, small for his age and a pen portrait of the author when young, knows all about bullying from his own previous experience. . ‘Corkscrews—brush-drill—keys—head-knuckling’—arm-twistin’—rockin’—Ag Ag—and all the rest of it.’

The three boys go on to give the two bullies in question a savage taste of their own medicine, reducing two whiskered 18-year-olds to otherwise shameful tears, with one of them also believing he is about to die. Given some of these boys were shortly going into the Colonial Service, it is as if part of their education at this army school was to learn how to administer effective interrogation techniques. The little chap in question makes a good recovery, but he was lucky.

Perhaps the most blistering unmasking of some of boarding schools’ darker realities is found in F.H.Anstey’s classic story Vice Versa, published in 1882. It starts with 15-year old Dick, about to return to his hated Crichton House School. Sobbing in front of his testy, rejecting father on their final meeting ‘in a subdued, hopeless kind of way,’ Dick miraculously manages, with the aid of the magic Garudâ stone, to reverse father and son into each other’s bodies. Mr Bultitude, who had just told Dick how lucky he was to be able to enjoy the innocent games and delights of childhood once back at school, now finds that he has to experience them for himself.

The result over one fraught week is an unmitigated disaster. While Dick at home in the shape of his father eats what he likes and plays games, the transformed Mr Bultitude is tormented day and night at school. Immediately unpopular with his contemporaries for trying to suck up to the headmaster, his ordeals include being kicked in the shins, jabbed in the spine and having his arm twisted round till it is nearly wrenched out of its socket. He also eats dreadful food, sleeps in ice-cold dormitories and suffers one terminally boring lesson in classics after another. Any attempt to assert what he calls ‘his rights’ is met with derision by pupils and masters alike. He is now in a largely lawless society where his threats to take out an action for assault against a bully or to write a letter to the Times complaining generally of his treatment mean nothing.

When one of the kinder teachers starts a similar lecture on how nice it is to be young, Mr Bultitude this time will have none of what he now declares is ‘miserable rubbish.’ Confronted by a particular tormentor, he is forced to admit that ‘I didn’t know there were boys like you in the world, sir; you’re a young monster!’ This novel’s sub-title, A Lesson for Fathers, is well chosen. When Mr Bultitude finally manages to run away he resolves during the subsequent chase that he will never be taken alive. This is no idle threat – he really means it.

Anstey himself was also unhappy at his first boarding school. But as he writes in his autobiography A Long Retrospect, this was not because of any particularly unpleasant teachers or boys. Rather, he describes himself as given to ‘moods of quite causeless depression and discontent with things in general….when it seemed to me that this world I found myself in was a rather wearisome affair.’ At school he describes how he ‘Never entirely shook off a feeling of some impending disaster which might fall when I least expected it.’ Only rarely beaten himself, he remained terrified of the cane, and although guiltless would tremble with nerves during various headmasterly fulminations visited on pupils during assembly and lessons.

As such, he is very like the character of Kiffin, the small boy in Vice Versa scolded for sobbing on his first train journey to school. ‘He was a home-bred boy, without any of that taste for the companionship and pursuits of his fellows, or capacity for adapting himself to their prejudices and requirements, which give some home-bred boys a ready passport into the roughest communities, His heart throbbed with no excited curiosity, no conscious pride, at this his first important step in life; he was a forlorn little stranger, in an unsympathetic, strange land, and was only too well aware of his position.’

This was not a child who was ever going to enjoy most boarding schools as they once were. Others could and did, and were more than happy in adulthood to wax nostalgic about the good time they had there. But Anstey is speaking up here for those pupils forever brooding over their lot ‘with a dull, blank dejection which those only who have gone through the same thing in their boyhood will understand. To others, whose school life has been one unchequered course of excitement and success, it will be incomprehensible enough – and so much the better for them.’

C.S.Lewis, who also hated his boarding school, wrote in his autobiography that Anstey’s novel was the only truthful school story in existence, painting ‘in their true colours the sensations which every boy had on parting from the warmth and softness and dignity of home life to the privations, the raw and sordid ugliness of school.’ Yet it is also possible that Anstey went some way to cancelling the important lessons he was getting across by making his whole story so funny. The headmaster Dr Grimstone is a brilliantly observed character, never at a loss for his next supremely pompous utterance. Mr Bultitude comes over as such a self-serving and unloving hypocrite that there is still comic satisfaction in his blusterings before one of his frequent come-uppances.

Whether Anstey’s novel had anything to do with it or not, boys’ boarding school stories after that too often found themselves settling into a comfortably facetious and generally escapist mode. Writers like Charles Hamilton, writing under the pseudonym Frank Richards, and who never went to a boarding school himself, produced hundreds of stories set in the imaginary Greyfriars School. Led by Remove Captain Harry Wharton, along with Frank Nugent, Bob Cherry, Hurree Jamset Ram Singh and Johnny Bull, this Famous Five band of pupils regularly thwarted bullies, unmasked other villains and always came out on top in any struggle with unpopular teachers. Popular, good-humoured, independent and adventurous, they led a charmed existence far removed from the daily lives of most of their huge cohort of readers.

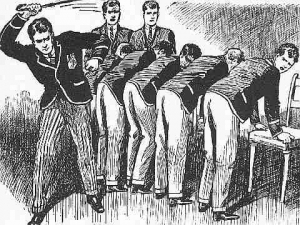

There is also among them Billy Bunter, the so-called ‘fat owl’ of the Remove, greedy, dishonest, always on the cadge and never learning from experience, his much emphasised grossness more or less precludes him from any normal feelings of sympathy from readers. Not bright enough to cover his tracks, he is regularly found out with many stories ending on his familiar cry of ‘Yaroo!’ as his sorely tried teacher Mr Quelch ‘thoroughly enjoyed himself’, as Hamilton sometimes puts it, by giving him a fierce beating. The Famous Five always find this highly amusing, but treating corporal punishment as intrinsically funny whoever it is visited upon, fat or thin, is surely one of the greatest betrayals of childhood.

No-one in Tom Brown’s Schooldays found Dr Arnold’s frequent floggings and thrashings at all funny, and for good reason. For in reality caning is not just humiliating; it also hurts, sometimes very badly. Witness this description of the experience taken from life rather than fiction, recorded in Roald Dahl’s autobiography Boy about a time when he was aged between seven and nine.

‘At first I heard only the crack and felt absolutely nothing at all, but a fraction of a second later the burning sting that flooded across my buttocks was so terrific that all I could do was gasp. I gave a great gushing gasp that emptied my lungs of every breath of air that was in them. It felt, I promise you, as though someone had laid a red-hot poker against my flesh and was pressing down on it hard. The second stroke was worse than the first.’

And yet school beatings continued to serve as laugh-aloud set-pieces, from weekly comics like the Dandy and Beano to Whack-O, a BBC television comedy starring the popular comedian Jimmy Edwards as the headmaster of Chiselbury Public School ‘for the sons of Gentlefolk.’ The credits opened with a cane twice smacking across the school name plate. The show was later turned into a film entitled Bottoms Up!

Corporal punishment was finally banned in all British schools in 2000, and with that went much of the humour that had been so perversely associated with it. Today boarding schools are by common consent much nicer places. But a recent study by Alex Renton, Stiff Upper Lip, presents a disturbing picture of what some of them were like at their worst – still well within living memory. Sub-titled Secrets, Crimes and the Schooling of the Ruling Class, much of it is based on the evidence of hundreds of fellow-sufferers who wrote to Renton in response to an article he wrote for the Times about his own unhappy time as a pupil.

Many of them mentioned sexual abuse from teachers, which apart from a few hints here and there was not a topic a children’s writer could have taken up until very recently. But there were other less controversial sad memories, particularly of loneliness and homesickness. Here is one from Renton himself, remembering aged just eight his first night at prep school in a dormitory, ruled over by two bossy ten-year-olds who threatened a beating if a boy made any noise after lights-out.

I remember lying with the pillow hard over my face to stifle the snuffles of homesickness, while also lying still as stone in order to keep the rusty old bed quiet. All three of us new boys were in the same bind. The relief when the officers found another boy crying and pulled his sheets back to beat him with the belt was enormous. The noise he made during the operation was cover for you to move your stiffened limbs in the bed and perhaps take the opportunity to sob a bit too.

The image of a small boy weeping on his first day at school is surely not one to be taken lightly. Yet in so many school stories this sort of example is treated at best with mild irritation, accompanied by the earnest hope that he will soon grow out of it. And so he might, but at what cost? Self-help groups now exist for those who see themselves as boarding school survivors still emotionally troubled by memories of past schooling. Obviously all sorts of issues come up in such groups including memories of criminal sexual behavior. But one recurrent theme is regret that they never felt able to talk at the time about their concealed grief. The gap between what parents benignly expected about what boarding school would be like and the nightmare it sometimes turned out to be was felt at the time to be so vast as to prove insurmountable. Those who did try speaking up too often met with incredulity leading to inaction, thereby sowing seeds of bitterness difficult to recover from.

Children’s novelists could at least have given an occasional voice to such pupils. Instead they chose to concentrate on escapist fantasy. Some of these authors may simply have not known what they were writing about, happy instead to continue mining a rich fictional seam popular among so many readers. Others must have had some idea of what sometimes went on, but chose to ignore it. In that they were just like those parents abused themselves at school who then sent their own children to suffer similar experiences.

Sometimes the boarding schools boy pupils attended were indeed pleasant, friendly places, remembered fondly in later life. But others were not, and those pupils particularly picked on or with a general inability to cope sometimes suffered trauma they are still coming to terms with years after the event. Where were the school stories that might have warned them about that?