Paul Foley presents a history and analysis of the cultural impact of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin.

As commemorations for the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising continue throughout Ireland, there have been many discussions on the impact of the rebellion on the political landscape in both Britain and the Irish Republic. Although the initial response to the armed uprising from the civilian population was one of indifference, it quickly turned to anger and hostility towards the volunteers. Once Britain subjected the rebellion’s leadership to secret trials and began executing them, this hostility was then re-directed towards the oppressor.

The direct political fallout from the Rising was the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. This in turn led to a vicious civil war. In 1949 the Irish Republic was finally declared, although the island remains divided and the consequences of the English conquest remain. Over the following 100 years since the small army of volunteers entered the City’s General Post Office (GPO), the doomed rebellion has entered folklore as a heroic and romantic episode in the country’s turbulent history.

There are many reasons for this. Clearly there is the genuine heroism of a smaller oppressed nation taking on the might of a huge empire. Certainly the cruel response by the British in executing 16 of the Rebel leaders ensured they would be considered martyrs to a just cause. But the romance comes from the background of the seven men who formed the provisional government. These were not professional insurgents or experienced political activists. They were idealists, poets and visionaries. Although their initial brand of Irish Nationalism may have been different, by 1916 their views and outlook for a New Ireland began to coalesce.

Of the seven signatories to the Proclamation read out by Padraig Pearse on Easter Monday 1916, four were accomplished writers and poets.

Thomas MacDonagh was a renowned poet and, along with Joseph Plunkett, edited the literary periodical ‘The Irish Review’. MacDonagh embraced the burgeoning renaissance in Irish literature, culture and language. He joined the Gaelic League but became radicalised by the industrial troubles of the early 20th century and subsequently joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). One of his last poems ’Wishes for my Son, Born on Saint Cecilia’s Day” was dedicated to his young son. The poem sets out his hopes for the young boy and for his future and that of his beloved Ireland:

But for you, so small and young,

Born on Saint Cecilia's Day,

I in more harmonious song

Now for nearer joys should pray-

Simpler joys: the natural growth

Of your childhood and your youth,

Courage, innocence, and truth:

These for you, so small and young,

In your hand and heart and tongue.

However MacDonagh was more than a poet. He wrote an award- winning musical cantata with the Italian composer Benedetto Palmieri based on the biblical story of the Israeli exodus from Egypt. He also wrote a number of plays. His best known was ’When the Dawn Is Come’ based on a rebellion against a tyrannical oppressor led by a seven strong army council. Although written before the Easter Rising had even been planned, the play had uncanny parallels with the later events.

The play was premiered at Ireland’s National Theatre, The Abbey, but MacDonagh became frustrated at the conservative nature of the theatre and its insistence at staging what he described as the ‘stereotypical portrayal of Irish themes’. His response was to establish a new avant garde theatre. ‘The Irish Theatre’, as it was called, produced plays from contemporary Irish playwrights as well as the works of European writers. His theatre was the first to stage Chekhov’s ‘Uncle Vanya’ in Ireland. He also introduced Irish audiences to Ibsen with a production of ‘An Enemy of the People’.

During the industrial turmoil of 1913 MacDonagh supported the workers’ struggle and helped found Ireland’s first teaching union, the ASTI. The eloquence of his writing is captured in the final letter to his wife before being shot by British troops:

I am ready to die and I thank God that I am to die in so holy a cause. My country will reward my deed richly. I counted the cost of this, and I am ready to pay it.

The generosity of his spirit was evident up to the end. While standing before the firing squad he declared:

I know this is a lousy job but you are doing your duty. I do not hold this against you.

A British officer commenting on the deaths of the Rising’s leaders said.

They all died well but MacDonagh, he died like a Prince.

MacDonagh’s close friend and fellow editor of The Irish Review, Joseph Plunkett, also served on the seven man military council. Although considered a bohemian for his unconventional lifestyle, he was a devout Catholic. Like MacDonagh he was highly regarded as one of the country’s leading poets. Most of his poetry was romantic, laced with heavy religious symbolism. As with most of the leaders of the Rising, Plunkett’s views on the Nationalist cause developed to reflect the need for an Irish state built around the social and humanitarian needs of the people. This development was in part due to his strong friendship with James Connolly.

In 'I see his Blood upon the Rose', he uses the crucifixion as a metaphor ‘for our need to go beyond the self in search for human meaning’. Despite having no military experience, Plunkett became the chief military strategist in the Rising. When asked by his son who Plunkett was, James Connolly said:

This is Joe Plunkett and he has more courage in his little finger than all the other leaders combined.

The romantic image of the Rising has often been attributed to Plunkett’s story. Suffering from TB he joined the insurrection a week after having surgery. But it was his marriage to Grace Gifford, herself an activist in the fight for independence, that caught the public imagination. Their wedding took place in the small chapel in Kilmainham Jail. He was led into the ceremony in handcuffs with a platoon of soldiers - with bayonets fixed - on guard. Grace described their honeymoon which lasted just 10 minutes:

During the interview the cell was packed with officers and a sergeant who kept a watch in his hand and closed the interview by saying, ‘Your 10 minutes is up now'.

Grace never saw her husband again. The following morning at dawn, despite his illness, he was shot. In his beautiful poem ‘To Grace’ Plunkett writes:

The joy of spring leaps from your eyes

The strength of dragons in your hair

In your soul we still surprise

The secret wisdom flowing there:

But never word shall speak or sing

Inadequate music where above

Your burning heart now spread its wings

In the wild beauty of your love.

Plunkett’s murder in Kilmainham, along with that of Connolly, were the catalyst that ignited the backlash against British rule and led to the guerrilla war between 1917 and 1921. When we think of James Connolly we immediately think of a great Marxist thinker and leader of the Irish working class. A man of immense stature, a prolific writer on Marxism and Irish Independence. His seminal works ‘Labour in Irish History’, ‘The Re-conquest of Ireland’, and ‘Erin’s Hope and the New Evangel’ remain key texts for modern Marxists.

But Connolly was also a poet, playwright and author of many ballads. Perhaps not in the same league as MacDonagh, his work was still highly regarded. His play ‘Under Which Flag’ about the 1867 Fenian Rising was performed in Liberty Hall only weeks before the Easter uprising. The lead character was taken by Sean Connolly (no relation), who sadly became the first volunteer to be killed during the capture of Dublin Castle. The play was never published but the full text is available in the Irish State archives. His most famous ballad was the rousing call to arms ‘A Rebel’s Song’:

Come workers sing a rebel song,

A song of love and hate,

Of love unto the lowly,

And of hatred to the great.

The great who trod our fathers down,

Who steal our children’s bread,

Whose hands of greed are stretched to rob

The living and the dead.

The leadership of the Rising nominated Tom Clarke as the Republic’s acting President, mainly because of his seniority and experience in direct action. However Clarke was not interested in the trappings of leadership. It was agreed that Padraig Pearse would become the interim President. Pearse’s nationalism grew from a love of the Irish language and its culture. He established a bilingual school, St Enda’s College. His poetry was well respected although it tended to paint a rather romantic picture of Ireland and was deeply influenced by his Catholicism. Although initially a supporter of Home Rule, by 1914 he was committed to the need for an armed rebellion to liberate Ireland.

In 1912 Pearse published his angry poem ‘Mise Eire’ in which he decries a people abandoning the fight for Ireland’s freedom:

I am Ireland:

I am older than the Hag of Beara.

Great my glory:

I who bore brave Cúchulainn.

Great my shame:

My own children that sold their mother.

Great my pain:

My irreconcilable enemy who harrasses me continually.

Great my sorrow:

That crowd, in whom I placed my trust, decayed.

I am Ireland:

I am lonelier than the Hag of Beara.

Recognising the failure of the Rising, Pearse declared as only a poet could:

When we are all wiped out, people will blame us for everything …… in a few years they will see the meaning of what we tried to do.

It didn't take a few years: shorty after his execution the people of Ireland began to fight back. The night before he died Pearse wrote his last poem ‘The Wayfarer’ which although a lament, showed a great calmness at his fate:

The beauty of the world hath made me sad,

The beauty that will pass;

Sometimes my heart hath shaken with great joy

To see a squirrel in a tree

Or a red ladybird on a stalk.

Although the remaining signatories of the Proclamation were not known for their artistic achievements they have, albeit indirectly, made a significant contribution to the cultural history of the Rising.

Tom Clarke, the oldest of the leaders, was a long time political activist and organiser. His prison memoirs ‘Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life’ was published posthumously in 1922. The book contains reflections of his 15 years spent in prison for his activities fighting for Irish independence. Clarke considered the diary as ‘mere jottings’ but its eloquence and lack of bitterness or self indulgence places it alongside the very best of prison literature, such as Gramsci’s ‘Prison Notebooks.’

Shortly before his death he wrote:

I and my fellow signatories believe we have struck the first successful blow for Irish Freedom. The next blow which we have no doubt, Ireland will strike, will win through, in this belief we die happy.

Sean MacDiarmada became the commercial manager of the campaigning Gaelic newspaper ‘An Saoirseacht” (Irish Freedom). Under his management the paper became more political. In an editorial it described British rule:

Our Country is run by a set of insolent officials, to whom we are nothing but a lot of people to be exploited and kept in subjection.

In 1915 he was imprisoned for sedition when he called on Irishmen to refuse to fight for the British in the first world war. His poetic last words before being shot by a firing squad continue to resonate with revolutionaries across the world:

I die that the Irish Nation may live.

Probably the least known of the seven signatories to the Proclamation is Eamon Ceannt, a quiet intelligent man who had a great interest in Ireland’s history. He joined the IRB in 1913 and became an executive member of the ruling council. He was more a cultural nationalist than a political activist. He was an accomplished Uilleann pipe player and in 1908 played for the Pope in Rome. He wasn't known for his writing although he was an impressive public speaker. He was unhappy at Pearse’s call to surrender, feeling that the rebels should fight to the death. This reluctance is seen in a statement he issued to the Irish Independent before his death:

I leave for the guidance of other Irish Revolutionaries who may tread the path which I trod, this advice, never to treat with the enemy, never to surrender at his mercy but to fight to a finish. Ireland has shown she is a Nation.

At 2.30AM on the 8th May 1916 he wrote a last letter to his wife:

My Dearest Aine

Not wife but widow before these lines reach you. I am here without hope of this world, without fear, calmly awaiting the end…What can I say? I die a noble death for Ireland’s freedom.

The cultural relevance of the 1916 Rising began much earlier than that fateful Easter. At the turn of the 20th century there was a re-awakening of Irish nationalism. A passive acceptance of colonial rule, which had settled on the country since the middle of the 19th century, was beginning to stir. Writers started studying the ancient Gaelic culture as a means of developing a modern Irish identity. The purpose was to build a cultural identity distinct from the British colonial power and through this develop an Irishness that could liberate the country and create a new modern progressive state. Gaelic clubs sprang up all over the country. There was a renewed interest in Irish literature and folklore and how to build a new Ireland, an Ireland that could end the terrible poverty, both economic and spiritual, felt under colonisation. Rebellion against the British Crown was no longer enough.

One of the clearest voices of this ‘new renaissance’ was the playwright John Millington Synge. For him the fight was to win not only a ‘Free Nation’ but also a different type of nation. His views reflected the words of James Connolly who in 1887 said:

If you remove the English Army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain.

Synge had been writing in Paris when he was advised by W.B.Yeats to return to Ireland. He did so and in the remote Aran islands immersed himself in Irish traditional culture. The result was his dramatic masterpiece ‘A Playboy of the Western World’. It premiered at the Abbey in 1907, which led to riots on the streets of Dublin. Most of the hostility was whipped up by Conservative Nationalists. The leader of Sinn Fein, Arthur Griffith, denounced the play as immoral. Padraig Pearse, a future leader of the 1916 Rising, said:

It is not against a Nation he blasphemes so much as against the moral order of the universe.

Pearse called for a boycott of the Abbey in response to its staging of the play. But within 2 years Synge was dead and Pearse had changed his view, describing the great playwright ‘a true patriot’ and acknowledging that “He baffled people with images which they could not understand”.

This episode highlights the speed at which Ireland was changing and the growing desire for the arts to be at the core of a free and independent country. The combination of a cultural re-awakening and a desire for a new and separate Ireland with an intellectual idealistic and visionary leadership, brewed a heady cocktail which ignited on Easter Monday, 24th April 1916, with the volunteers’ march on key installations in the country’s capital.

What is interesting is the response of the non-combative cultural elite to the Rising. W.B.Yeats, one of Ireland’s greatest poets, appeared to be conflicted. Prior to the events of Easter 1916 he was mocked the Irish Nationalists, and denounced violence as a means of achieving independence. In his poem Easter 1916, we see this conflict. His initial ambivalent feelings towards the leaders of the movement for independence is caught in the poem’s opening lines:

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words....

But later he recognises the wanton murder of the leadership had changed things, changed them utterly and the use of ‘terrible’ and ‘beauty’ in the same sentence shows his conflict at the terrible loss - yet beauty - of their sacrifice:

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

In contrast, Ireland’s other great writer, James Joyce, remained silent. He never made any direct comment on the events of that Easter. He did, however, push to have his Dublin novel ‘A Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man’ published in 1916, which many believe was his contribution to the ongoing debate on the Rising’s merits. Within the book, he does appear to suggest that he disavows petty nationalism and that art is the higher calling:

I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it call itself my home, my fatherland, or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or as art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defence the only arms I will allow myself to use-silence, exile, and cunning.

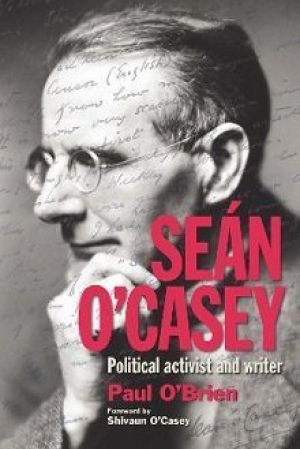

Sean O’Casey’s position is more complex. The great playwright was originally an integral part of the Independence movement and in particular the fight for a socialist republic. He was responsible for writing the constitution of the Irish Citizen’s Army, the armed protection established by Jim Larkin following attacks on workers during the 1913 Lock-out. However he fell out with his comrades and sat out the rebellion. Bitterness and self regard seemed to eat away at his soul, which may have clouded his judgement on the events of 1916. But it wasn't until the early 1920s when O’Casey wrote his famous trilogy of Dublin Plays that his true feelings became clear. ‘Shadow of a Gunman’ and ‘Juno and the Paycock” deal with the civil war and its aftermath while the third, ‘The Plough and the Stars’ directly addresses the Easter Rising.

‘The Plough’ was premiered 10 years after the Rising but the rancour felt by O’Casey towards his former comrades does not appear to have diminished. The Irish Marxist and Connolly biographer, C. Desmond Greaves, suggests that O’Casey’s protagonist Jack Clitheroe only joins the rebellion out of vanity and because of what people might say if he didn’t. He argues that O’Casey deliberately set out to ‘present the Rising and the motives of those who took part in a poor light’. Student protesters to the play, led by Frank Ryan, a Republican IRA organiser who later distinguished himself in the fight against fascism in Spain, objected to the implication that the men of the Citizen Army were motivated by vanity and ambition.

The other big beast of Irish Letters, Bernard Shaw, was more critical of Irish Nationalism. For him the Rebellion was foolhardy. However, he was outraged by the indiscriminate murder of the leaders and campaigned to have the executions stopped. His anger was palpable in a revised preface to ‘John Bull’s Other Island’ written in 1929:

Having thus worked up a hare-brained romantic adventure into a heroic episode in the struggle for Irish Freedom the victorious artillerists proceeded to kill their prisoners of war in a drawn-out string of executions. Those who were executed accordingly became not only national heroes, but martyrs whose blood was the seed of the present Irish Free State. Among those who escaped was its first President. Nothing more blindly savage, stupid, and terror mad could have been devised by England’s worst enemies.

This very much reflects the sentiment in Pearse’s graveside oration at the funeral of O’Donovan Rossa on 1st August 1915:

But the fools, the fools - they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.

One glaring omission in much of the history of 1916 is the lack of recognition for the many women who not only contributed to the armed struggle but also the cultural life of the time. Unforgivably, many important women have been lost from the story of the birth of the Irish Republic, mainly because the achievements of women were not recorded and future historians tended to examine major events from the perspective of the men involved.

This year’s commemorations have tried to address this, with some specific events dedicated to the hundreds of women who fought for, cared for, and wrote about the tragic rebellion. Current Irish President, Michael D. Higgins, writing in SIPTU’s centenary edition of ‘Liberty’ stressed the importance to the revolution of the fight for equality and emancipation:

As such, the emancipation of women was an integral part of the social transformation called for by the leaders of the Irish Citizen Army, such as Francis Sheehy Skeffington and James Connolly. The atmosphere of equality that prevailed between men and women in the ranks of the ICA reflected the vision held by many Irish and International socialists of the time, for who women’s emancipation was a pre-condition for any just society.

Many women had become radicalised during the 1913 lock-out and become active in trade unions. Connolly declared in 1914 that the oppression of women and the oppression of the workers by “a social and political order based on private ownership of property” were inseparable, and he recognised what was the double burden on women.

Women occupied many positions of influence in the fight for independence. Helena Maloney was an activist in the socialist and trade union movement since 1903 when she joined ‘Inghinidhe na hEireann’. She became editor of its feminist paper ‘Bean na hEireann’. She was also the General Secretary of the Irish Women’s Workers’ Union (IWWU) who won 2 weeks holiday for her members. In later years she became a founding member of Friends of Soviet Russia.

The cultural heart of the country was a significant part of her life. She was an acclaimed actress who prior to the rising played opposite Sean Connolly in ‘Memory of the Dead’ a play written by Casimir Markievicz, husband of Constance. Maloney was also an active combatant in the fight for Dublin castle.

Other leading women who campaigned for Irish independence and were active over the Easter week were Dr Kathleen Lynn who championed the cause of women’s health and welfare, and acted as Medical Officer to the rebels during the fighting. Constance Markievicz was second-in-command of the battalion that occupied the Royal College of Surgeons. Following her arrest she was sentenced to death but later this was commuted to life in prison. Markievicz became the first woman elected to Westminster following the limited suffrage won in 1918. Other women playing a leading role in 1916 were Winifred Carney, leader of the Irish Textile workers’ Union and Secretary and aide de camp to James Connolly; and Madeline Ffrench-Mullen, who was an officer in the ICA and commanded a small band of volunteers at Stephen’s Green.

As Lucy McDiarmid explains in her book ‘At Home in the Revolution’ the women’s strength and determination were extraordinary. In response to the sound of the firing squads, women prisoners began dancing the intricate 16-hand reel. This act of solidarity was not only brave and defiant, but must have been hugely unnerving to their captors.

As well as her soldier’s role, Constance Markievicz was an actor, appearing in a number of plays at the Abbey alongside Maud Gonne the activist, actress and muse of W.B.Yeats. She was hugely influenced by James Connolly, whose death greatly affected her. Dedicating a poem in his honour she wrote:

You died for your country my hero love

In the first grey dawn of Spring

On your lips was a prayer to God above

That your death will have helped to bring

Freedom and peace to the land you love love love everything.

Her sister, Eve Gore-Booth, was a respected poet and author who shared Constance’s passion for Irish Nationalism. The women differed in that Eve, a pacifist, could not support the use of violence by the rebels, no matter how just their cause. But that didn't diminish her support for the aims of the revolt nor for its leaders. Shocked by the callous murders of the leadership, she wrote her beautiful, short and poignant poem ‘Comrades’ as a tribute to the bravery of those that gave everything for their country:

The peaceful night that round me flows,

Breaks through your iron prison doors,

Free through the world your spirit goes,

Forbidden hands are clasping yours.

The wind is our confederate,

The night has left her doors ajar,

We meet beyond earth’s barred gate,

Where all the world’s wild Rebels are.

It is a disgrace that Alice Milligan’s name has almost disappeared from the annals of great Irish writers. Milligan, an Ulster protestant, threw herself into the cause of Irish independence. She was a prolific writer, contributing essays and stories to over 70 journals. She also wrote numerous plays, novels and short stories. As a poet she wrote epic poems on the theme of ancient Irish folklore. In a 1914 edition of 'The Irish Review 'Thomas Macdonagh described her as 'the greatest living Irish poet'. During the Rising she dedicated herself to fighting for prisoners’ rights including the right to be granted political status. An anthology ‘Hero Lays’ contains some of her best poetic work, including ‘Owen Who Died, A ’67 Man’ in memory of the 1867 Rising:

Right off to the coast-line of Connacht

’Twas he carried word

To the boys who were waiting upon it,

Of how Ireland was stirred.

His hand set a beacon alight

To burn on by day and by night

Sudden his coming and flight-

He has gone like a bird.

The 1867 Rising stuttered into life with a few sporadic skirmishes across the country. Having been undermined by disorganisation and police spies, the revolt soon petered out. The interesting fact is that the Rising was launched with a Proclamation declaring an Irish Republic based on social justice and equality. 50 years later a very similar Proclamation announced the declaration of an Irish provisional government in 1916.

Since 1169 Ireland has been occupied first by the Normans then the English. In those 847 years, thousands of its people have died either in the cause of liberty or by the cruelty and neglect generated by the occupiers, resulting in mass expulsions from the land and devastating famine. The culture, language, and national identity has been through long periods of suppression but the spirit of the people has kept its rich cultural history alive.

Many historians and political commentators have discussed the merits of the Rising. Some argue that it was an unnecessary sacrifice as the political climate was moving towards Home Rule, and that eventually Ireland would have had a measure of Independence. But that is the point: the British solution was a form of devolution but falling short of total independence. It took the 1916 revolt to provide the impetus for total separation. Although today that dream is still not fully realised, there can be no doubt that the sacrifice of the volunteers in 1916 brought the Free State and Republic much closer.

As we celebrate the centenary of the momentous events 100 years ago, what is the Rising’s legacy? I suggest that the political and cultural legacies have developed in completely different ways. The revolution brought together idealists with very different views on the nature of a new Irish Nation. However, they were all agreed that it needed to be a nation built on social justice, equality and with an internationalist outlook. Cultural enrichment of the people was to be a cornerstone of any new constitution.

Unfortunately, after the civil war in 1922, the reactionary Catholic elite took control. An economically conservative Ireland under De Valera created an era of stagnation. De Valera’s staunch Catholicism allowed the Catholic Church to grab control of the country’s education system, and ensured the Church would have the final say on the moral values of the young nation. Despite this conservative and reactionary cloud hanging over the new State, the cultural development of Ireland continued to progress both internally and across the world. Notwithstanding the oppressive use of censorship by the Church and state, a rich vein of novelists, playwrights and poets continued to use their creative imagination to challenge, educate and develop a cultural pathway for today’s writers and artists.

There is an unbroken line from MacDonagh, Plunkett, Yeats and Joyce through to Brendan Behan, Elizabeth Bowen, Molly Keane, Eava Boland, Patrick Kavanagh, Samuel Beckett, Seamus Heaney, Edna O’Brien, Paula Meehan, Jennifer Johnson, Anne Enright, Sebastian Barry. And there are hundreds more whose creative beauty was born from their forebears’ terrible struggle.

Perhaps it is fitting to leave the last word to Ireland’s great modern poet, the late Seamus Heaney. Written in 1966 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of 1916, his poem “Requiem for the Croppies” uses the 1798 revolution as a metaphor for the legacy of the heroes of 1916 on a future Ireland:

Terraced thousands died, shaking scythes at cannon,

The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave.

They buried us without shroud or coffin

And in August…the barley grew up out of our grave.