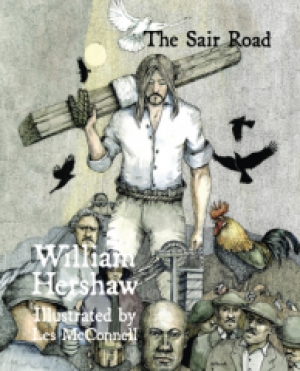

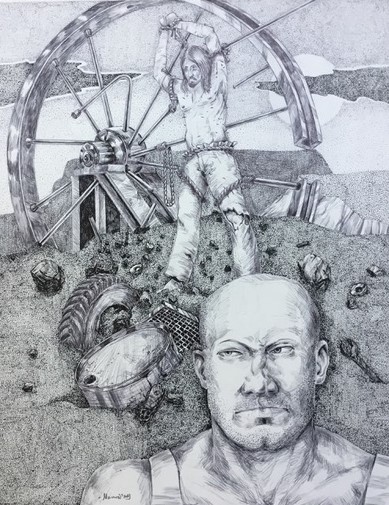

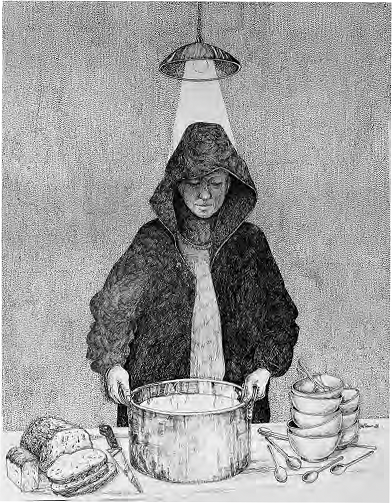

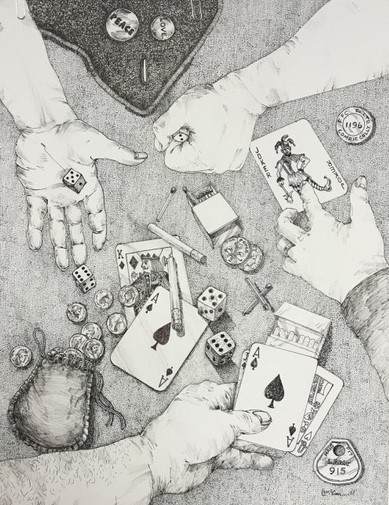

Jim Aitken reviews The Sair Road, by Willie Hershaw. The header image and all others in this review are by Les McConnell, the illustrator

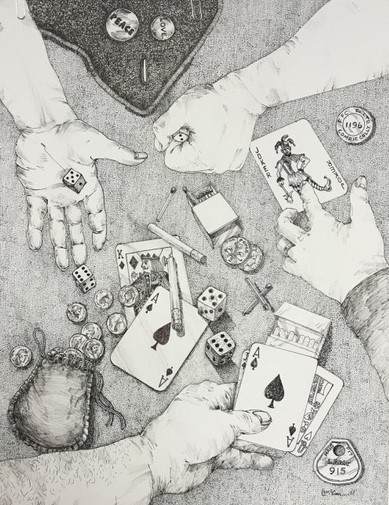

Far from creating any ‘gude and godlie’ kingdom in Scotland as a result of the Reformation there in 1560, by the time of Robert Burns (1759-96) Presbyterianism was being openly satirised. Religious hypocrisy was one of Burns’ most constant themes in his poetry. This is no more evident than in ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ where Willie believes that he has become one of the elect by the simple fact of seeing himself chosen by God to be one of the elect. And while he chastises others like Gavin Hamilton because ‘he drinks, an’ swears, an’ plays at cartes (cards)’, Willie exonerates himself for lifting ‘a lawless leg’ upon Meg and for having had sex with ‘Leezie’s lass…three times.’ He should be excused for the latter offence on the grounds that he was ‘fou ‘(drunk). Such transgressions Willie sees as utterly without any theological or moral implication for himself but the same man would condemn others fervently for similar transgressions.

The Christian virtue of ‘judge not lest you be judged’ has no reference point in Willie’s religious view. The obsession with the sins of others created the dialectic of the self-righteous and the damned. With so much to be frowned upon it is fair to say that Scottish culture suffered from such a censorious atmosphere. Righteousness, after all, meant always being right.

It is therefore understandable that in James Hogg’s ‘The Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824)’ that it would be the Devil that made an appearance. In this incredible novel a fanatically self-righteous Robert Wringhim is encouraged to kill his more rounded and sporty brother, George. The figure of Gil-Martin as Devil incarnate utilises the religious fanaticism of Robert to commit fratricide.

The novel is set in the turbulent times of the 17th century when Scotland was waging religious war both at home and abroad during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Hogg has two narratives in this book, one by an Editor and the other by Robert himself. The Editor is a smug man of the Enlightenment who believes that civilisation and progress are both constant and linear. He looks back on the fanaticism of a previous era with horror, viewing the excesses of such times as primitive and barbaric. What makes this novel so modern is our clear understanding today that such excesses are always with us – when we think of the two World Wars of the 20th century, of the Iraq war, the rise of Daesh, the rise of the far right, national populism and the threat of environmental catastrophe in our short century so far.

Hogg’s masterpiece raises such important notions of duality and without it we would not have had Stevenson’s ‘The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ or ‘The Testament of Gideon Mack’ by James Robertson.

It was not until 1860 that Christ made his most significant appearance in Scottish culture. It was in a painting by William Dyce (1806-64) of Aberdeen called ‘The Man of Sorrows.’ Dyce was associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and played a part in their early popularity. It was in fact Dyce who introduced Rossetti, Holman Hunt and Millais to John Ruskin and the spirituality in some of Dyce’s painting owes much to the Pre-Raphaelites.

Victorian Britain was a brutal place, with imperialism abroad and servitude at home, and the Pre-Raphaelites sought to go back in time to a more romanticised world, often inspired by the poetry of Shakespeare, Keats and Tennyson. While they did create an artistic renewal and expressed a mission of moral reform revealing piety, they also showed the struggle of purity against corruption. Ruskin particularly approved of their detailed treatment of nature. However, their canvases largely featured much earlier historical eras, while the social reality around them was ghastly. In this they were not entirely different to Prince Charles, with his horror of so much of modern architecture, or to John Major and his reverie for an England where you came out from Evensong and headed for a warm beer on the village green, watching cricket.

What made Dyce’s painting so memorable – at least for Scots – was that the figure of Christ was sitting on a Scottish Highland hillside. Dyce, of course, would have been intimate with such locations himself and that is probably why he chose such a setting. However, the implication of such a setting was considerable. There is plenty of space for Christ to contemplate in such a wilderness because a few decades earlier the Highlanders had been cleared from the land to make way for sheep. ‘The Man of Sorrows’ can be seen to be at one with the men and women who were so brutally evicted from their lands. Such an interpretation –possibly unintended by Dyce – would nonetheless be made by many Scots. The sorrows felt by Christ were also the sorrows of those who once lived in this wilderness. Furthermore, the sorrowful Christ of the Highland hillside would clearly have known that the church in Scotland did little to prevent such suffering, by siding instead with the landowners and the gentry.

Though we live in a largely secular era today (though not so secular in the land of Mammon, the USA), the figure of Christ, as expressed in the Gospels, can still inspire. What churches have done – or not done – in his name cannot be attributable to him. He was and remains a radical and a revolutionary figure who sought nothing more than peace, love and sharing based on communal values.

Christ is a communist and God is a miner

Call that rebirth and resurrection if you like. He was on the side of the poor, the victimised, the marginalised and the oppressed. His ministry was itself ‘good news for the poor.’ It is inconceivable in a world where the poor and oppressed are still with us that he cannot be seen as relevant. George Bernard Shaw, in his Preface – a work far more interesting than the play it introduces – to ‘Androcles and the Lion (1916)’ called Christ ‘a communist.’

His story inspired an array of different people and groups as diverse as the Levellers of the 17th century, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, Keir Hardie, Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela, along with untold billions over the last two millennia.

Love richt and heeze the ferlous gift o grace!

So for Jesus to turn up in the Fife coalfield of the 20th century seems perfectly in keeping with his historical influence at other times. The versatile William Hershaw, who is not just a poet but also a dramatist, folk musician and Scots language activist, tells us in his introduction to ‘The Sair Road (2018)’ that ‘the Thatcher years ‘were ‘the most significant period’ in his life. At the time of the Miners’ Strike of 1984-5 he ‘was a young teacher in Fife’ working not so much at the chalk face but at the coal face, where many of the students he taught would have been the sons and daughters of miners.

The idea behind ‘The Sair Road’ must have formed in an earlier poem he wrote called ‘God the Miner’. The words of this poem are inscribed on a sculpture by David Annand called ‘The Prop’ and installed in 2007 in Lochgelly. It was in fact part of the Lochgelly Regeneration Project brought about after the death of a once proud industry. The words from the poem seem entirely apt because, as God creates, so too does the miner. They are indistinguishable:

God is a miner,

For aye is his shift,

Heezan his graith he howks in the lift.

Always working (aye is his shift) God lifts (heezan) his tools (graith) and digs (howks) in the sky (lift). In the second verse we read:

God is a miner,

Thrang at his work,

Stars are the aizles he caws in the mirk.

Here we are told that God is constantly busy (thrang) and that the stars are the sparks (aizles) he strikes (caws) in the dark (mirk). These lines not only offer a poetic response to the work of creation but to work generally because labour can – and should – be afforded dignity because it is labour itself that is the source of all that is created.

The Fife coalfield was ravaged during the Thatcher years and neglected during the years of Blair and Brown. With the death of an industry came the death also of the NUM and, saddest of all, the death of that precious experience of community. From ‘God the Miner’ in 2007 Hershaw must have been howking away inside his poetic imagination to have come up with ‘The Sair Road.’

A Christian is a Socialist or nocht

This collection is also written in Scots, which is fitting because the Fife tongue still uses a great many Scots words and miners would certainly have used many of these words. The miners were a special workforce, and no more so than in the Fife coalfield. While the term ‘Red Clydeside’ is well known, ‘Red Fife’ could easily have challenged Clydeside for radical politics. In 1935 it was the Red Clydesider William Gallacher who became Communist MP for West Fife until 1950. And though our media loves to peddle the idea that to be a Communist you had to have attended Cambridge University and become a spy, the reality was that Cowdenbeath had the largest Communist Party Branch of anywhere in the UK, and members there were almost entirely miners. The socialist credentials of Fife are second to none.

‘The Sair Road’ is structured to parallel the Stations of the Cross. Hershaw, however, has adapted them to form what he calls ‘The Lochgelly Stations.’ There is also an introductory poem before the Stations called ‘Apocrypha 1: Airly Doors’ and after the Station sequence there is ‘Apocrypha 2: Efter Hours’ along with three further poems that seek to sum up not only what has gone before but what could come after.

There is, Hershaw tells us again in his Introduction, ‘no theological consistency or orthodoxy in ‘The Sair Road’ and Jesus the Miner ‘has little time for organised religion.’ In the poem ‘The Lord Lous (loves) a Sinner’ the following lines confirm this sense of an independent mind:

The Kirk needs the pious

Tae fill up her pews

But the Lord recruits sinners

For guid men are few.

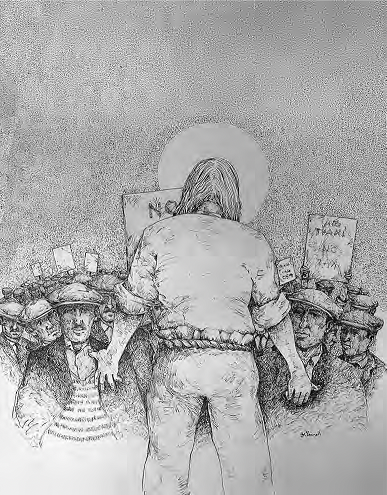

The action flits through the 1920s, when there was a lockout of miners in 1921, and moves on to the General Strike of 1926, when there was another lockout after that strike. The miners’ strike of 1984-85 is implied in all the action and invoked cleverly after Jesus the Miner is ‘liftit’ for preaching his gospel of love:

The neist day he was bound tae staund in coort

Condemned by the Sanhedrin, Daily Mail,

Thatcher and McGregor, the BBC,

Chairged wi riot, unlawful assembly,

The braggarts feart he micht owercoup their world

And like mad dugs settled tae bring him doun.

As he sat in the Gethsemane Plots thinking on his struggle ahead he was told – ‘You’re liftit Trotsky…Judas turned a scab.’ The archetypal name for a rebel – Trotsky – is applied to suggest how dangerous Jesus’ words have been to the status quo. And Judas – just as before – is the archetypal name for a traitor.

The names of the Apostles have a Scots twist to them. Jesus calls them his ‘feirs’ (friends) and they are named as Jamie, Mattie, Si, Wee Jock, Andrae, Tam and Big Pete. They are also his boozing buddies as they often hang out in the local Goth Bar. In no way could Jesus the Miner be set apart from others in this community. His spirituality and conviction may make him seem ‘other’ but he is very much a part of the mining community in all other respects.

Support the striking miners? Never, naa,/I winnae lift a haund, I'll see it faa.

The Lochgelly Stations mirror well the original story, and are also well applied to the mining community Jesus the Miner finds himself in. One good example of this is replacing Pilate with Ramsay MacDonald. He washes his hands of the whole sorrowful business at the end of the General Strike, just as Pilate did in the New Testament. Hershaw uses a particularly descriptive Scots word to suggest how the Labour leader feels about it all – ‘MacDonald girnt.’ Girning in Scots means not just moaning but doing so with lathers of self-pity. In his speech MacDonald ‘girns’ about his lot. He tells Jesus the Miner, ‘Socialism, Labour are juist bit words.’ Though progress is slow, he says, it will come ‘through the ballot box, no blackmail.’

These words could so easily have been spoken by Neil Kinnock when he was leader of the Labour Party during the strike of 1984-5. The South Wales miners dubbed him Ramsay McKinnock for not supporting them. Kinnock, of course, went on to become an unelected EU Commissioner, and he now sits in the unelected House of Lords. The same man complained – as the Tory press of his day told him to – that the miners should have had a ballot, which seems rather ridiculous today as the former son of a miner now sits with what Burns called ‘cuifs’ (fools) clad in ermine, in the House of Lords.

There is one key idea in ‘The Sair Road’ and that comes at Jesus’ trial. He is charged with the ‘wittin (knowledge) that he brocht: A Christian is a Socialist or nocht.’

How can it be that the rich and exploiter class are often the ones who attend church on a regular basis and claim to be Christian? How is it that the hapless Mrs May went to church, when as Home Secretary she made vans run around London with the words ‘Go Home’ printed on their side? These vans were directed at people of colour who had lived here for 50 years. How can she profess her Christianity while apparently holding others in such disfavour? How could she have led a political party of the rich for the rich, while overseeing Victorian levels of inequality and maintain she is a Christian?

The answer, of course, is the same as it has always been – easily. Her Prime Ministerial resignation speech showed how delusional she had been politically – so why should delusion not be part of religious faith either?

The Letter of St. James tells us ‘faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.’ And ‘works’ meant good works like helping the poor and not adding to their number. To be Christian, at least according to its founder, you have to ‘do unto others as you would wish them to do unto you.’ Without active concern for the poor, the victimised and marginalised, your professed faith is rather empty. Burns railed against religious hypocrisy in his day and Hershaw is simply saying the same today. What is different though is that Hershaw’s Jesus himself rails against such rank religious hypocrisy.

When Mrs Thatcher came and addressed the Church of Scotland General Assembly in 1988 she told them, ‘Christianity is about spiritual redemption, not social reform.’ Jesus the Miner would no doubt reply to this ‘you cannot have one without the other.’ Jesus of the New Testament would similarly agree, especially when we recall his words in Matthew 19:24, ‘It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God.’ It is the multi-millionaires and billionaires who should be afraid because of what they have done and what they continue to do.

This is where Jesus the Miner and Jesus of the New Testament have such a powerful message. Both preach love for all, including your enemies. All will be forgiven and all it takes to be forgiven is a change of heart. This is the essence of the Christian message. This is the great magnanimity of that message; this is the theological simplicity of it all. As with most theories, however, there is often the problem with praxis. Because the rich are so powerful they want to maintain their position of supremacy over others by keeping their riches – and continually adding to them – by keeping others down.

When Jesus the Miner is ‘flung in their jyle’ (jail) he is also scourged by ‘the Polis’. He is ‘punched and kicked’ as ‘Centurions waved tenners in his face.’ They called him ‘commie scum’ and said, ‘This kicking’s juist the stert o mair tae come.’

That kicking of anyone who stands up to the rich has been taking place for a long time now. The early Christians were persecuted for their belief, yet it was their persistence with that belief that ended slavery in the ancient world. The Hebrew word ‘anawim’ describes the lowest of the low, the scum of the earth and it was these people who became the first followers of this new faith. Once an idea takes hold, Lenin said, it can become a material force. That was certainly true of Christianity, and like socialism it has never been properly practised internationally because the rich and powerful have never allowed either to be properly practised.

It has been suggested that when the Emperor Constantine de-criminalised Christianity in 313 and converted to it on his deathbed, and later in 380 when the Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of the Empire, that the faith became compromised. The rich and powerful could use it for their own purposes. After this, of course, the Church split in two between a Catholic west and an Orthodox east, and then during the Reformation there came into being countless new Protestant churches. Jesus the Miner speaks for no church and only speaks for himself and what he says is remarkably like the original Jesus.

Although the original Christian message may have been compromised there have been many followers in all traditions who have stayed true to that message. It was the former Archbishop of Olinda and Recife in north-eastern Brazil, Dom Helder Camara, who famously said, ‘When I give food to the poor they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food they call me a communist.’

There were many priests and theologians in Latin America who developed what was known as liberation theology. Two of the most famous texts were ‘A Theology of Liberation’ (1971) by Fr. Gustavo Gutierrez and ‘Jesus Christ Liberator’ (1972) by Leonardo Boff OFM. Liberation theology was all about bringing ‘good news to the poor’ again, as Jesus had originally intended. Jesus the Miner would surely approve of them.

With the arrival of Pope John Paul II, such theologies and practices were frowned upon. Under the tutelage of Cardinal Ratzinger from the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, an Instruction went out against the practise of liberation theology called ‘Libertatis Nuntius’ in 1984. This was followed up by a Papal visit to parts of Latin America and a finger-waving Pontiff was shown on the BBC news telling off Boff in Brazil, and the poet-priest Ernesto Cardenal who had joined the first Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The reason this was shown was because this was a Pope fiercely opposed to socialism and maybe this was why the media seemed to warm to him.

After the death of John Paul II the new Pope was Benedict XVI – the former Cardinal Ratzinger. He has since resigned, and it was widely believed that he did so because he could not deal with the corruption inside the Curia, along with all the extensive cover-ups of clerical abuse now being exposed internationally. It has been left to Francis I to deal with this.

Capitalism is the dung of the Devil

Pope Francis would have personally known of liberation priests who were murdered in Argentina by the junta there, for serving the poor. He may well have met Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was murdered by El Salvadorean death squads in their fight against leftists in 1980. While Romero was not a liberation theologian, he was on the side of the poor, and he spoke out against their poverty and social injustice. Pope Francis has called capitalism ‘the dung of the Devil.’ He wants bridges rather than walls built between peoples, and wishes migrants fleeing poverty and war to be treated with love and compassion. Jesus the Miner would like the sound of that.

What he may not like the sound of is the new theology that has spread into Latin America from the United States. The gap opened up by Libertatis Nuntius has enabled Protestant Evangelicals proclaiming what is known as ‘prosperity theology’ to make inroads in a continent that was once largely Catholic. Their Christian fundamentalist influence has helped secure the Presidency of Bolsonaro in Brazil.

According to Mary Fitzgerald’s recent article in ‘openDemocracy’ (24 May 2019) over $50 million in ‘dark money’ has come into Europe from American religious conservative groups associated with Trump in the last decade. This money has funded campaigns that are dear to the far right, such as ending LGBTI rights, and ending the reproductive rights of women, as well as securing Europe from ‘Muslim invaders.’

This rhetoric has also railed against EU elites and has led to a fair crop of far-right representation at the recent EU elections. Steve Bannon, in his base at the Certosa di Trissulti monastery – a two hour drive south-east of Rome – has declared that Pope Francis is the enemy because of his mission for the poor and for his support of migrants. Religion has always been disfigured by the rich, powerful and unaccountable, with agendas that use religion for their own self-aggrandising political and economic ends. And any national populist turn in Britain or in Europe as a whole will simply continue that age-old exploitation.

He pushed brillo pads doun Grandi's lungs

In Station 5 of Hershaw’s poem, we hear about the terrible things done to miners and their families by King Coal. We are told he was a ‘spine-snapper, baa (testicle) – squeezer…..bairn-beater…..compensation-refuser..…match-fixer..…inquest-wrangler…..sulfur-choker…..telegram-bringer.’ In a grim reminder of what the miner’s life was like, we are told King Coal ‘pushed brillo pads doun Grandi’s lungs.’ All the horrible respiratory diseases are contained in this image. King Coal ‘mashed up our ambitions intae potted hough…he’d hypnotised us no tae believe in futures.’

These are real sentiments that must have been held by many a miner down the years but what did hold them together was their solidarity with one another. To survive down in the bowels of the earth you needed that solidarity with your fellow workers. It got you through your shift, and when you came up to the surface that solidarity was still there. This solidarity was also supported and strengthened by the National Union of Miners.

In 1973 the NUM paid for a bus of Chilean refugees fleeing from the scourges of Pinochet’s regime, a regime supported by the US to try out the new shock therapy of monetarist economics. The bus travelled from London to Cowdenbeath where the refugees would be housed. Thousands of miles from their homeland, the Chileans saw and heard the pipers playing and marching them to their new homes. Their homes had toys for the children, blankets on their beds and warm coal fires burning as they entered their new houses.

Here was room at the inn, true Christian charity of the most generous: here was international working-class solidarity at its finest. And this charity, this solidarity was delivered by a group of workers who, like the ‘anawim’ of the ancient world, were looked down upon and reviled by the rich for challenging their rule.

Today, this inspiring recollection is all the more sad, because last year in Cowdenbeath where King Coal is now absent, a Boyne ‘celebration’ was held by the Orange Order, addressed by Arlene Foster of the DUP. This event was the antithesis of what this area once represented. The CP within the NUM had successfully challenged the blight of sectarianism that seeks to divide workers. While our environmental consciousness today would not condone coal mining, the great loss of working-class solidarity is still something to be lamented.

The solidarity of all who are oppressed

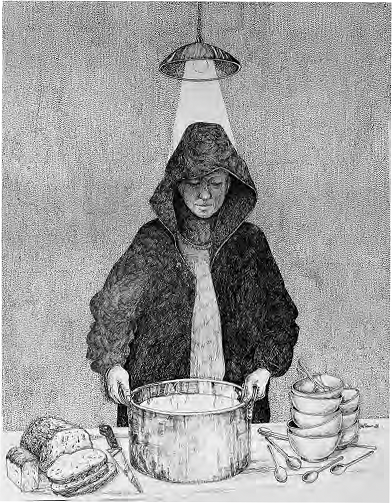

Unlawfully jailed, victimised and blacklisted it is ‘The Wummen o the Soup Kitchen’ (Station 8) who ‘kept saul and body thegither’ for Jesus the Miner. By mentioning these women Hershaw does not merely conjure up the followers in the Gospel accounts who were women – his mother Mary and Mary Magdalene, a former prostitute, being among his most faithful followers – he also helps us to recall the incredible contribution miners’ wives made during the 84-85 strike. Their activism and sacrifice was phenomenal. And just as those with power and wealth seek to divide worker from worker so they also try to do the same between men and women. It is the solidarity of all those who are oppressed that they fear most and that is why they must be divided.

The wummen o the soup kitchen kept saul/And body thegither syne

‘The Wummen o the Soup Kitchen’ were the heroines who had ‘smiles and faith/ And breid (bread) and soup they biggit (built-up) better men.’ Jesus the Miner had sought their help after he was ‘blacklistit fae ilka (every) pit in Fife.’ This was because, after the Great War, he had said in 1921,’This is nae land for heroes comin hame.’ He had told the ‘dochters (daughters) o the coalfield ‘greet nae for me’ (don’t cry for me) but ‘mourn for yersels, and for yer stervan bairns’ (starving children). Here he aligns himself with the poor and this was natural for him because he too is poor and made poor by those in power.

The painful route Christ took walking the Via Doloroso is cleverly paralleled as Jesus the Miner seeks to come to the aid of his fellow miners trapped down in a mine shaft. While he manages to ‘bring thaim tae the surface’ he found there was ‘nae hamewird passage up’ for himself. He writes a last message with a piece of chalk onto a wall of coal, and it is written for ‘wee Jockie.’ He asks him ‘tae tak care o ma Mither’ and ‘to luik out for our dear comrades’ and to ‘screive (write) doun our gospel tale.’

The use of the word ‘comrades’ here is interesting. The word is usually used on the left to suggest not just friendship but a brotherly or sisterly recognition that both parties are engaged in the greatest challenge of all and that is the liberation of mankind. The spiritual struggle and the political one are inexorably linked here as Jesus the Miner writes this word on the wall.

You are fogien. This Setturday nicht, I trow/You'll dance wi your Jean upby in the Goth

By way of re-assuring ‘The Guid Thief o the Lindsay Pit’ (Station 11) that, despite his foolishness in lighting up a ‘sleekit (sly) Woodbine’ that ‘blew aa Kelty up’ and killed and maimed many miners, Jesus tells him, ‘You’ll dance wi your Jean upby in the Goth …this Satturday nicht.’ However, this hope seems dashed as the pit props were made of cheap timber and ‘the ruif (roof) came doun on tap o Jesus back.’

And remarkably, echoing the historical crucifixion of Christ, Jesus the Miner trapped underneath timber, pit props and stones ‘lay there greetan (crying) in the daurk/Whiles bluid and watter skailt (spilled) fae out his side.’ And he said seven words – ‘Oh faither, why has thou forsaken me?’

Many miners have died this way, but Jesus the Miner is clearly no ordinary miner. He represents all miners, he represents the NUM and he represents the broader working class itself. The destruction of this industry, prepared well in advance by Ridley and Thatcher, was designed to smash not just an industry and an irritant union, but to put the working class back in their place. This brutal event has given the ruling class the rotten fruits of foodbanks, zero-hours contracts, non-unionised workplaces, Universal Credit, rising homelessness and a hundred other rotten fruits besides. It could be said that the Crucifixion of Jesus the Miner is in fact the Crucifixion of the working class.

The Inquiry found 'mistakes had been made'......The Pit was closed in 1910.

As Jesus languishes at the bottom of a shaft this becomes his tomb. Station 13 ‘Laid in a Tomb’ is the only poem throughout the sequence that is written in English. The expressive and effusive use of Scots is banished in favour of the colder and more callous use of English that can hide its deeds behind the words it uses. All the governmental buzzwords are here in this short poem – ‘mistakes had been made’……‘further recommendations’……‘future improvements’……‘no individual was deemed to blame for the accident’……‘due to the financial outlay’……‘geological difficulties’……‘too dangerous to reclaim the body.’

Thousands of miners’ wives have read such letters after fatal accidents concerning their husbands. The language used here from the inquiry is the language of power. It is a language that anaesthetises thought for a while, as the bureaucratic register deliberately obfuscates where culpability really lies. It brings to mind Hillsborough, the Bogside and Grenfell.

Blessit are thaim wi a drouth for richt

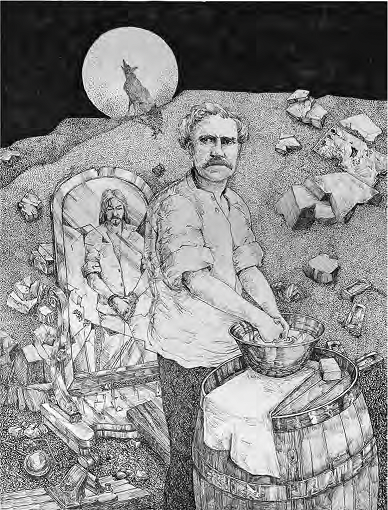

In ‘The Ballant o the Miner Christ’ (Station 14) Jesus has now become Christ because he has ‘maistered Daith.’ Hershaw tells us here, ‘This tale’s a baur (joke), a comedy.’ There is no need for tears. Instead, because Jesus mastered death ‘Let fowk (folk) get fou (drunk), let aa rejoice.’

In ‘Apocrypha 2: Efter Hours’ it is fitting that Jesus should turn up in the Goth and meet with Tam. Jesus tells him it is ‘Nae miracle – ye hinnae seen a ghaist.’ Cleverly too Hershaw has Jesus tell Tam that he is not in any hereafter but in ‘the here and nou (now).’ And what needs to be done ‘here and nou’ is what should always have been done before – ‘Let our leid (language) aye be love.’ Again, Hershaw has taken us to the essence of the Christian message in all its utter simplicity.

In ‘Spare me nae Beatitudes’ there are two lines that seem to represent what is at the heart of ‘The Sair Road’ – ‘Blessit are thaim wi a drouth (thirst) for richt: They will get unco fou.’ The demand for ‘richt’ is not really a demand for right and certainly not a demand for righteousness but a demand for justice, for social justice.

As a result of the demise of the mining industry and the subsequent attacks on the working class as a whole, former mining areas – like many other de-industrialised areas – are now full of ‘smack-heids’, ‘junkies,’ ‘drunkarts,’ ‘jaikies,’ ‘hameless,’ and ‘gangrels’ (beggars). They have all fallen through the pit shafts of social and personal disintegration.

But this ‘sair road’ that all the casualties have to follow – and because of our existential condition as social beings, we are all casualties – will find justice and redemption one day. Effectively, the resurrection of Jesus the Miner is the hoped-for resurrection of the working classes. They have been, and still are, walking ‘the sair road’ but there is no reason to say that they will keep walking this road. They may see the light and climb the mountain to their eventual redemption. It should be ‘here and nou’ but it will come nonetheless. Many genuine socialists and true Christians believe this.

Or to put it another way it is similar to Antonio Gramsci’s formulation of ‘The pessimism of the intellect and the optimism of the will.’ Beckett’s work illustrates how we all walk the same ‘sair road,’ the same existential road, aimlessly groping our way in the dark. Unlike George Osborne’s ‘we are all in this together’ when he can protect himself with his wealth from life’s adversities, ‘the sair road’ offers no protection for those with money. Along ‘the sair road’ we truly are in this all together. Or as the old adage has it – you can’t take it with you.

In the final poem ‘Isaiah 2:2-6’ there is the hope and the promise of ‘paice for ivirmair’ (peace for evermore) when our guns will be ‘wrocht (turned) intil ploushares.’ This is a fitting conclusion to ‘The Sair Road.’

Love, death, religion and revolution

The collection raises many issues and implications. It was a brave decision by Hershaw to write it and to write it in Scots. The use of Scots actually makes the poem all the more credible because to write on a subject like this in English would be to draw forth issues concerning the words Jesus the Miner uses. Would he have to talk as he does in the Gospels? How would he sound among Fife miners if he spoke English? What kind of accent would he have? The use of Scots makes Jesus the Miner exactly like everyone else. There is no difference in accent and therefore no class division either. Hershaw chose Scots well in ‘The Sair Road.’

If Hershaw’s choice of Scots was a good one then his decision to show that Jesus the Miner ‘has little time for organised religion’ was an even better one. The most obvious point here is that organised religion – especially in the West (though not the USA) is in decline. There is also a widespread revulsion against the growing number of cases coming to light of clerical sexual abuse. This is particularly true of the Catholic Church. By keeping Jesus the Miner away from any notional sense of church involvement, Hershaw avoids any taint of denominational preference or having to defend such a preference.

‘The Sair Road’, however, raises many issues that have had a past debate and continue to be discussed today. It was Dostoyevsky in ‘The Brothers Karamazov’ (1879-80) who has Ivan Karamazov tell the tale of ‘The Grand Inquisitor’. Christ returned to earth, he says, during the time of the Spanish Inquisition in Seville. The local people recognised him and gather round Seville Cathedral to welcome him. Inquisitors eventually arrest him and Christ is told by the Grand Inquisitor that the church has no need of him today. Christ is to be burned at the stake but during the night before this is to take place, the Grand Inquisitor visits him in his cell. Christ listens to him without speaking himself. The Grand Inquisitor then decides to allow Christ to leave ‘into the dark alleys of the city.’

Christ had been condemned by the Inquisition for giving us all the freedom to walk ‘the sair road’ with all that implies for us. The Church, maintained the Grand Inquisitor, kept everyone happy by taking away their freedom. Jesus the Miner, like all miners and all workers, chooses ‘the sair road’ which ultimately brings resurrection and redemption. And just as the ordinary people in Seville recognised and loved Christ, so too the ordinary miners and their families have taken Jesus the Miner to their hearts.

There is also a well-known sketch by the Irish comedian, Dave Allen, that similarly deals with this conflict between Christ and the Church that claims to carry his message. As reverential music is being played while the Three Wise Men look down upon the baby Jesus in his crib, a rush of fervent Irish nuns appear and take hold of the child saying, ‘Well now, we will just be making sure that he is brought up the right way.’

In one of Terry Eagleton’s recent books ‘Radical Sacrifice’ (2018) we can find something akin to the idea inherent in ‘The Sair Road’. Eagleton’s work over many decades has been inspired by Marxism in his work on literary criticism and cultural theory, yet his Marxism also shows a debt to his earlier Catholicism. Thomas Docherty in his ‘Literature and Capital’ (2018) talks of Eagleton’s ‘quasi- religious turn’ and it could be that such a ‘turn’ maybe only became apparent after the publication of ‘After Theory’ (2003). This study sought to re-invigorate the left by saying that the age of theory is surely over now. In attacking the postmodernists who claimed that the era of what they called ‘meta-narratives’ was over – ie religious systems, philosophical systems and political ones like communism – Eagleton claimed that they made little mention of the most dangerous ‘meta-narrative’ of all that is capitalism.

He argued that it was time to cast aside the empty relativism of the postmodernists and to re-engage with the big issues all over again. He could well have been saying that ‘man does not live by bread alone.’ For him the big issues meant love, evil, death, morality, metaphysics, religion and revolution. Marx, it should be remembered, said something similar – ‘Philosophers have only interpreted the world. The point is to change it.’ Eagleton would support this comment, but would add a caustic comment of his own saying that the postmodernists have not really interpreted very much.

‘Radical Sacrifice’ looks at the role of the ‘scapegoat’ in both primitive and modern societies. Jesus was a scapegoat in his time as were his followers. Creating scapegoats enables the status quo to remain the status quo. The miners in 84-85 were the scapegoats and today it is Muslims and migrants. Both ‘Radical Sacrifice’ and ‘The Sair Road’ seek to re-engage with issues of love, death, religion and revolution.

Similarly, some of the recent work by Marxists who profess their atheism nonetheless offer penetrating insights into the revolutionary potential of early religion. Alain Badiou in 1997 brought out ‘Saint Paul: The Foundations of Universalism’. Badiou considers St Paul to have been a profoundly original thinker who still has the revolutionary potential to inspire in the 21st century. It should be remembered that Paul was the one who took the message of Christ across the ancient world and helped set up the first Christian communities. He lived an impoverished life himself. He was Christianity’s first theologian if you like.

One of his deepest insights was to say in Galatians 3:28: ‘There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, neither male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.’ Here is the principle of Christian egalitarianism which ended slavery in the ancient world. It did so through love, through the unconditional love of others. Such a principle is not a million miles away from ‘The workers have nothing to lose but their chains. Workers of the world unite.’ That unity is required more now than ever before.

Slavoj Žižek has engaged in recent years in dialogues on faith in ‘The Monstrosity of Christ: Paradox or Dialectic?’ (2009) with John Milbank and in ‘God in Pain’ (2012) with Boris Gunjevic. Both texts discuss faith in the 21st century and dissect its revolutionary potential. This places ‘The Sair Road’ in extremely good company. The ongoing catastrophe that is capitalism should make us think deeper than ever before. To go forward you must always check the past by digging deeper into it than ever before also.

The sodgers played at pitch and toss,

Hey caw through, though doul the daw,

Wi Jesus nailed attour the Cross.

His love rules aa!

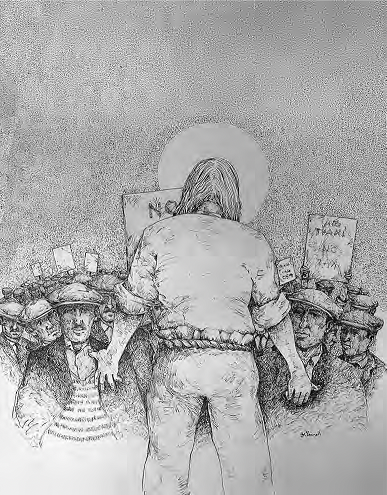

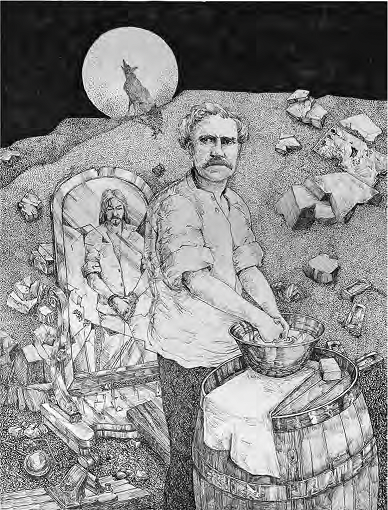

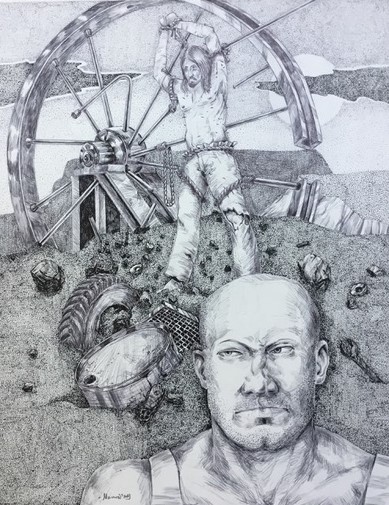

The final word on this remarkable book should go not to Hershaw but to his wonderful illustrator Les McConnell. His drawings do more than illustrate the meanings of the poem, they extend and enhance them, providing a fine accompaniment to the fine ‘The Sair Road.’ His drawings that accompany the text are sensitively rendered and enhance the poem tremendously well. They bring out both the detailed particularity of the scenes depicted, and the more abstract connections being imagined in the poem between Jesus’ revolutionary message and the struggle of the miners and the working class as a whole for economic, political and spiritual liberation – the communist dream of a society where 'love rules aa!'

The Sair Road by William Hershaw, illustrated by Les McConnell, is published by Grace Note Publications, price £20.