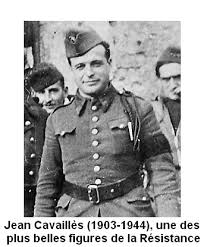

What's the source of alienation? Jim Aitken reviews 'Soil and Soul' by Alistair McIntosh

Soil and Soul was first published in 2001 and it was a thoroughly well-received book. In his Foreword to it, George Monbiot described it as ‘a ground-breaking book.’ The plaudits that McIntosh was given were indeed wholly justified and it seems that Monbiot was the most perceptive of all McIntosh’s commentators:

It (Soil and Soul) is a first step towards the decolonisation of the soul: the essential imaginative process we have to undergo if we are to save the world from the political and environmental catastrophes that threaten it.

There is clear recognition here that there is political responsibility for all the chaos in our world today. Monbiot goes further and suggests that there is a need ‘to develop daring and imaginative means to tackling the powers that have deprived us of ourselves.’ We could add that ‘these powers’ have been engaged in ‘depriving us of ourselves’ for several centuries now. And because ‘these powers’ have not been sufficiently challenged in all this time these powers have become emboldened with ever greater rapaciousness, which has resulted in ever greater deprivation at the expense of ourselves.

Monbiot recognises that McIntosh’s book is ‘one of the most striking challenges to corporate power in British history ’and he further recognises that McIntosh has in fact developed ‘a radical politics of place.’

While this assessment is accurate, Monbiot fails to address in greater detail what those political powers are that are responsible for depriving us of ourselves. This failure by Monbiot mirrors the failure of McIntosh himself, in his otherwise terrific book. Both writers seem unable or unwilling to use the word ‘capitalism’. Yet, the subtitle of Soil and Soul does give a clear hint of what the book is furtively all about – People versus Corporate Power.

It is rather odd in a book of nearly 300 pages that capitalism is mentioned less than a handful of times. Yet, the book itself is a tour de force account of activism against corporate power that also proved successful. Indeed, the book is a celebration of that success.

The radical politics of place

The book is written in two parts. The first part is called Indigenous Childhood; Colonial World and allows the writer to look back on his idyllic childhood growing up on the island of Lewis in the Western Isles of Scotland. The second part is called The French Revolution on Eigg and the Gravel-pit of Europe.

The first part concerns ‘the radical politics of place’ that Monbiot referred to, where McIntosh and others managed to clear out the lairds (owners) of the island of Eigg and prevent a super-quarry from decimating a part of Harris.

McIntosh’s account of both his childhood and his knowledge of how colonial powers changed the relationship the indigenous people had with their environment is deeply insightful. What is particularly interesting is his unearthing of Celtic Christianity and its relationship to the natural world and to the rhythms of the people. It possessed a poetry that grounded the people with their environment, with their communities and their place in the world.

That, of course, changed with the coming of Catholicism and Roman centralisation. Later this changed again from Catholicism to Calvinism. Change, as we know, is constant but McIntosh seems to analyse such changes as somehow phenomenological. The sustainable lifestyles associated with the Hebrides gave way – just like everywhere else – to what McIntosh calls ‘Capital -intensive production methods’ that had ‘usurped ecology and human community. The ecosystem of place had started to unravel.’

While McIntosh uses the term ‘capital-intensive’, and also talks of a ‘culture change’, he uses language in a similar vein to Monbiot who talks of ‘the powers.’ McIntosh later in the book talks of ‘the Domination System’ but these terms seem to deliberately attempt to obfuscate the onward march of what threatens the world and that is, and has been, plain old- fashioned and constantly re-fashioned capitalism.

Why the fear to use the word? Is it because the language of the Left may scare some people away? Is it that a new language of ecological and environmental activism must somehow separate itself from the language used traditionally on the Left? Whatever the answers to these questions, the fact is that capitalism will continue to ravage the land, the sea and people everywhere in order to make profit.

This is, after all, the raison d'etre of the system. The social and environmental horrors of this world did not suddenly appear like rainfall, they were created by the powers of capitalism to make money. Culture change does not suddenly happen like snowfall, it is engineered by the powers of capitalism. Ecological damage? Tough. Human communities ravaged? Again, tough.

Yet McIntosh does talk about alienation and how the dissociation between people and place can set in. He refers to the radical humanism of Erich Fromm and his work To Have or To Be? (1976). The title and the question mark at the end of it opened up a discussion about the alienation that comes with consumerism. ‘Being’ for Fromm has a more spiritual and creative sphere whereas the pursuit of ‘having’ can never bring lasting happiness and will always separate the haves from the have-nots. Greed, envy and aggression must give way to sharing, to shared experience which is more genuinely productive and far less wasteful. McIntosh praises this book – and rightly so – since it seems to accord with his mission as a ‘spiritual activist.’

McIntosh uses the word ‘activism’, a word familiar on the Left but he separates himself from those who may see their activism in more secular ways by saying that his activism is distinctively spiritual. Yet the activism of those who took part in Black Lives Matter protests, those who campaign against war and the arms trade, those who challenge poverty and inequality, those who march for Palestine, those campaigning against low pay, job losses, privatisation, women seeking an end to misogyny, people of colour seeking an end to racism, people maintaining that no human being is illegal, people active against climate chaos and those who seek redress in a myriad of ways against a system that only craves profit before people – all these activists are spiritual too. Their response to what they all see as wrong comes from a moral awareness, an interior understanding of what is unjust, unfair and unacceptable. This is something all communists, socialists, environmentalists and others have in common – it is a moral revulsion at what the powers, the domination system, the constant culture change of capitalism is doing to us all and to our world.

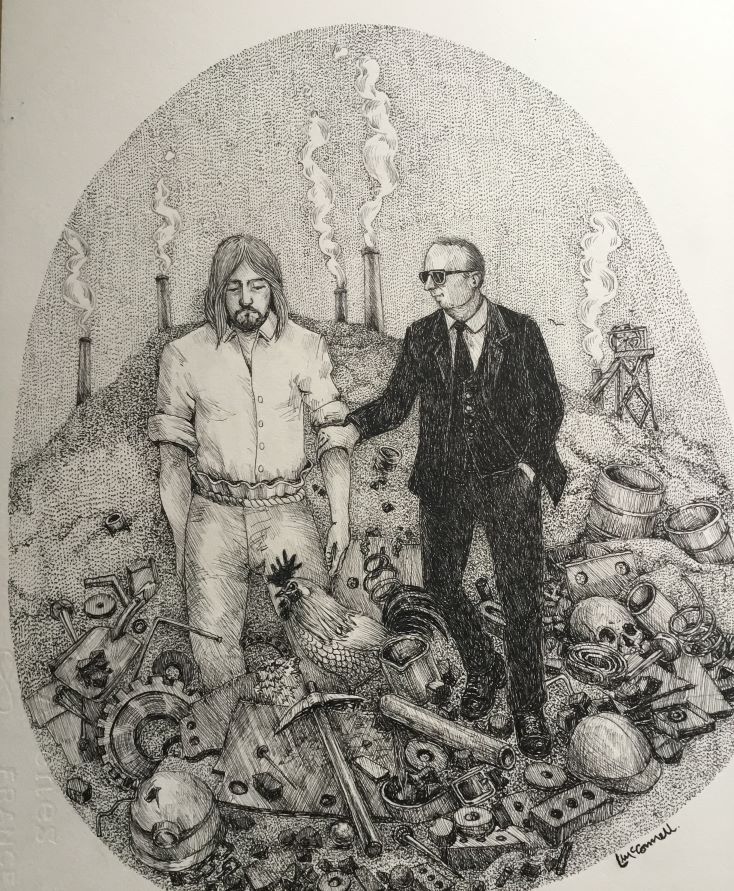

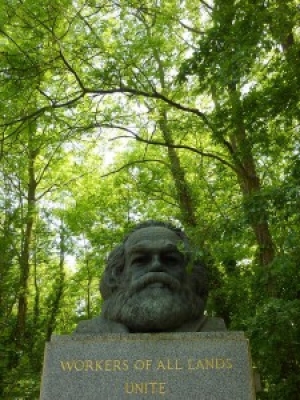

This is the source of alienation. It is created out of the competitiveness for greater profits. Marx refined Hegel’s concept of what he called ‘the rabble’ to what Marx called ‘the proletariat.’ Writing in The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844) Marx talks about alienated labour. The worker who labours to produce commodities for the market has no relationship to what he or she produces. He or she is merely a wage slave who requires their wage to subsist. This is as true today as it was in the 1840s. This is but one aspect of alienated labour because the labourer will always be external to what he or she produces. It is made for someone else’s profit and someone else’s possession. Political economy, for Marx:

…hides the alienation in the essence of labour by not considering the immediate relationship between the worker and production. Moreover, Labour produces works of wonder for the rich, but nakedness for the worker. It produces palaces, but only hovels for the worker; it produces beauty, but cripples the worker; it replaces labour by machines but throws a part of the workers back to a barbaric labour and turns the other part into machines. It produces culture, but also imbecility and cretinism for the worker.

Capitalism must simply have more to make more money. Both nature and human beings are exploited for this end. Alienation as a concept came to be explored in literature, art and in psychoanalysis. The Frankfurt School of thinkers of which Fromm was a member, as McIntosh tells us, took an intellectual leap after the publication of Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts in 1932 in Moscow – which McIntosh does not tell us. Fromm’s classic To Have or To Be? seems a fitting work for McIntosh to argue his ‘spiritual activism’ case but in other works by Fromm there is a clear challenge to modern capitalism, particularly in his book The Sane Society (1955).

This text received equal praise and condemnation on its publication – the condemnation came as a result of its truth, which many did not wish to hear. The Frankfurt School, it should be remembered, sought to fuse their understanding of Freud with their analysis of Marx. Another important member of this group of thinkers was Herbert Marcuse. In one of his best-known works, Eros and Civilisation (1955), he clearly has a play on the title of his work with the title of Freud’s Civilisation and its Discontents (1929). What Marcuse shares with Fromm is an understanding that modern civilisation has a demand for our sublimation, our conformity. And the need to continually progress our productivity increases our own domination – a word used by McIntosh in Soil and Soul.

The pathology of capitalism

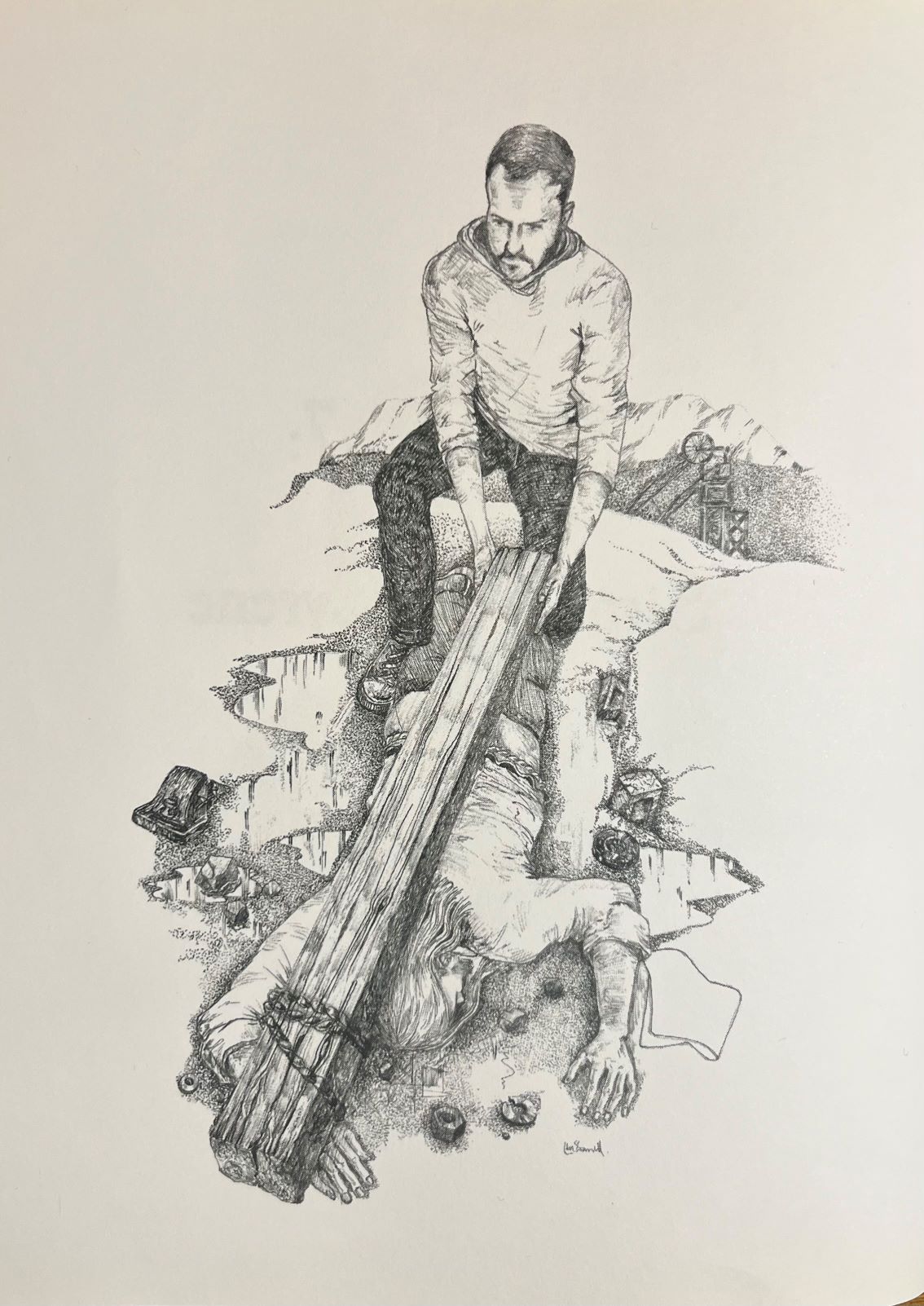

Marcuse and Fromm both agree on the need to redefine what is meant by progress and account for the violence we see all around us through the failure of our economic and political system to make use of our capacity for love and reason. This failure results in the development of the reverse where the forces at play in our economic and political system seek to control life totally or destroy it.

This is exactly what we are seeing today in Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, Haiti and elsewhere and the root cause of all this mayhem is the need to compete and control markets, resources and people. And when war breaks out there are vast profits to be made from selling arms. This is the pathology of capitalism. McIntosh seems to understand this instinctively, but without any reference to marx, Marxist thinkers or to capitalism itself as the culprit in its own chaos.

His book recalls two tremendous campaigns that were both successful. The first one concerned getting rid of the laird of Eigg, Keith Schellenberg. McIntosh played a crucial role in this and he must be duly commended. Schellenberg was a privately educated Englishman with German ancestry who made his money in business. McIntosh and others assembled a broad spectrum of people to challenge his right to rule. There were plenty of meetings, publicity campaigns, fundraising, newspaper articles, and media interviews.

While McIntosh maintains all this activism was spiritual, many would see this as good old-fashioned class struggle. Certainly, that is exactly what Schellenberg thought, as he labelled the campaigners communists and called McIntosh a Marxist. Strange as it may seem, one could have a tinge of sympathy for Schellenberg since as the laird of Eigg and a member of the ruling class he had been told since birth that those who challenge your right to rule are communists. We see this in the United States as Donald Trump ludicrously calls Kamala Harris a communist and labels her ‘Comrade Kamala’.

Eigg eventually gained its freedom through a community buyout scheme introduced by the Holyrood parliament. It was a wonderful achievement and victory for the people of Eigg and McIntosh played an important part in this. The various people who came together formed what those on the Left would call a broad democratic alliance. McIntosh eschews such language, yet it is undeniable that without a broad democratic alliance there could not have been victory.

A similarly broad democratic alliance of forces managed to prevent a super-quarry from destroying a mountain and the way of life on Harris. Capitalist expansionism will go to isolated communities like Harris, underneath the sea or into space in search of resources and profits. There is nothing new in this. Destruction of a mountain with all the necessary logistics and infrastructure required to do this – as well as noise and dust pollution – would have had a devastating impact on Harris. This would have led to alienation of the human community from its environment on a grand scale. McIntosh played a pivotal role in campaigning against the super-quarry.

One great idea he had was to bring over from Canada the Mi’Kmaq warrior chief Stone Eagle to aid the campaign. He seemed to fit the required media attention his presence would bring, by having had his native lands once exploited and despoiled. The recruitment of Stone Eagle to the campaign was inspired. He gave his blessings to the mountain, to the land and to the people of Harris whose ancestors were once cleared from their land and sailed to places like Canada. His presence was considerable. It was a warrior from the Cree tribe in the nineteenth century who famously said:

Only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will we realise that we cannot eat money.

McIntosh does not use this quote, but it shows a powerful understanding of the deranged irrationality that is inherent in capitalism. It is doubtful if the Cree warrior had read Marx – yet he sums up exactly what capitalism is about.

The community that came together to prevent the super-quarry won a marvellous victory against corporate power. What McIntosh stressed throughout his book is the importance of community, of people coming together. This solidaristic approach is exactly what capitalism loathes, peddling the constant refrain of individualism.

One aspect that is crucially important today is the ongoing development with Hi-Tech and the advance of AI. When McIntosh published Soil and Soul in 2001 there was clearly huge advances being made technologically. Everyone was online and mobile phones were upgrading themselves each year. In 1995 the world’s first online dating site was launched in the form of Match.com. A few years after McIntosh’s book would come Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005), Twitter (2006) and Instagram (2010). And, of course, there is so much else besides. Foucault could see long before all this happened that a paradigm shift had occurred whereby the traditional mode of production had now given way to the mode of information. This is clearly where we are today and Big Data is buying and selling all this information.

Yet twenty years before Foucault’s death in 1984 it was Marcuse in One Dimensional Man (1964) who could clearly see at his time how ‘Technology serves to initiate new, more effective, and more pleasant forms of social control and social cohesion.’ Those were prophetic words indeed for that is where we are today.

The feudal lords of the digital

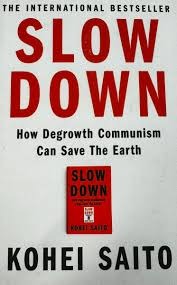

Two recent books analyse the current malaise even deeper. Byung-Chul Han in Capitalism and the Death Drive (2019) suggests we are now living in a digital panopticon. He tells us ‘structurally this society does not differ from the feudalism of the Middle Ages.’ Han then goes on to affirm:

The feudal lords of the digital, like Facebook, give us some land and say: ‘Cultivate it. You can have it for free.’ And we cultivate it exhaustively, this land. At the end of it all, the feudal lords return for the harvest. This is an exploitation of communication. We communicate with each other, and we feel free when we do so. The feudal lords extract capital from the communication. And the Secret Services monitor them. This system is extremely efficient. There are no protests against it because we live in a system that exploits freedom.

The information we willingly give on our phones, tablets and computers is stored and sold. Data is huge business and with it all comes widespread surveillance. Today’s largely online workforces are all constantly monitored, given targets within a culture that is performance -driven. Han suggests that this culture is effectively a form of self-exploitation. It leads to burnout and depression. This is contemporary capitalism, and this is our alienated condition today.

Han’s book argues that capitalism is not merely destructive ecologically but is directly responsible for all the social catastrophes around us and for our mental collapse. Conjure up Edvard Munch’s The Scream of 1893 and see how accurate a depiction this painting is for all alienated workers and individuals struggling to cope with their mental health in an uncaring world. Brutal competition, he claims, ends in destruction. And the engineered compulsion in today’s workplace to perform produces an emotional coldness and general indifference not only toward each other but to ourselves. This is the latest manifestation of alienated labour.

Yanis Varoufakis argues that Technofeudalism (2023) has in certain respects killed capitalism, not by any advent to socialism but by a regress to feudalism. Again, the information we now freely give is effectively the consumer providing free labour. This too is a form of self-exploitation. Each time we order commodities online, book holidays, order theatre tickets we provide free labour that is stored in what Varoufakis calls ‘cloud capital.’ And every time we order from Amazon we are effectively paying Jeff Bezos rent. Rent was what defined feudalism and the sheer amount of business that is now done online by consumers is in the breathtaking order of hundreds of billions of pounds.

The owners of today’s big tech companies are essentially the new feudal overlords. And, as we know, they can also sow misinformation and create dangerous political ruptures. It is widely commented upon that many of these overlords based in California’s Silicon Valley not only support Trump but can visualise a Hi-Tech takeover where politicians are no longer required. This is not only the ultimate wet dream for these overlords, it is the completion of the alienation project that Hegel and Marx detected centuries ago.

Clearly, Alastair McIntosh could not have read these texts in 2001 because they were not yet written but the technological developments were clearly leading in that direction. Interestingly, many of our thinkers like Slavoy Žižek and Alain Badiou have gone back to Hegel, since alienation for him was not the complete negative that it was for Marx. It was communism for Marx that would finally end alienation. But according to Hegel alienation can be productive, even necessary, for the development of what he calls the True. When alienation is encountered it is obviously traumatic, but this simultaneously can lead to Freedom. Being alienated means coming to terms with an inner negativity that defines our subjectivity and this process can bring us to our own common humanity.

The people of Eigg, Harris and Silicon Valley all share a common humanity with everyone else on the planet. For McIntosh the secret is the coming together and the fight for community:

If humankind is to have any hope of changing the world, we must constantly work to strengthen community. We need, first, to make community with the soil, to learn how to revere the Earth.

Yes to that! But McIntosh then says:

We need to make community of human society. We need to learn empathy and respect for one another so that people get the love they need…. It means understanding and overcoming the psychology of racism and exclusion, sharing wealth and skills… shifting from competition to co-operation in politics and economics.

This sounds remarkably similar to what Marx was advocating. Community and communism come from the same Latin root communitas meaning public spirit. McIntosh is free to define himself as a spiritual activist and he has undoubtedly shown terrific campaigning skills. Yet what he did was in a sense the actions of a communist who sought to stimulate and develop a greater public spirit, and an increase in the common good. The struggles he was a part of successfully created a much greater public spirit, and have contributed hugely to the common good.

Many would welcome his advice today since communitarianism and communism are both sought to liberate mankind from grotesque levels of alienation designed to sublimate our creative capacities to win a better and fairer world for all. Soil and Soul can certainly be a good companion on that journey.