The Quest for the Materialist Jesus: Part 2

In Part 1, I argued that a historical materialist understanding of Jesus in a world of competing class interests needs to be revitalised, updated, and developed further by a new generation of historians. Before we turn to these issues, it might be helpful for readers unfamiliar with how we go about reconstructing the life of Jesus to have an outline of how we might go about this task.

Sources

The best sources we have for Jesus are probably all from the first century in the decades after his death (c. 30 CE). While there is some potentially useful material in the letters of Paul (e.g., 1 Corinthians 7.10–12), the payoff is limited as Paul’s concerns (as far as we know) were elsewhere. The best materials available are the New Testament Gospels, or rather the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke. The Gospel of John presents Jesus as an elevated figure to the extent that he was in some ways equal with God (e.g., John 5.18; 10.30–33) and who was executed after he raised Lazarus from the dead (John 11.38–57).

While the other Gospels have their own theological agendas, they do not reflect these ideas which were part of theological speculation at the end of the first century onward rather than from closer to the time of Jesus. Moreover, John’s explanation for the death of Jesus obviously did not happen. Whatever the historical accuracy of the other Gospel accounts, the claim (for instance) that Jesus was put to death for turning the tables of dove-sellers and moneychangers at a tense, busy festival in Jerusalem (Mark 11.15–18) is at least a more plausible explanation than a story about raising someone from the dead.

That leaves the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke. The Gospel of Mark is widely accepted as the first Gospel and a source for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Matthew and Luke also share very similar material that is not found in Mark which has led to the hypothesis of a shared (but now lost) source which scholars have labelled “Q” (from the German “Quelle,” meaning “source”). It has also long been argued that Matthew and Luke additionally had independent sources. This is the standard explanation for understanding the Gospel sources, although there have been regular challenges to the consensus, such as (among others) the claim that there was no lost source and that the similarities between Matthew and Luke can be explained by the argument that Luke copied Matthew.

This is a huge area of scholarly debate and I simply note that my own preference is something like the conventional model, while being open to the idea that Luke may have also known Matthew. Sometimes, additional sources from the second century (e.g., non-canonical Gospel of Thomas) are invoked, but it is not clear that they add much more to the understanding of the historical Jesus.

From this, scholars have tried to develop a set of criteria (the so-called “criteria of authenticity”) designed to take us back to the historical Jesus. For instance, the “criterion of multiple attestation” usually involves the argument that if an idea or theme is found in independent sources which do not involve copying one another (e.g., Mark and Q) and in independent forms contained within (e.g., parables, sayings, conflict stories) then we are close to the historical Jesus.

These criteria have come under heavy criticism over the past decade and rightly so. At most they can tell us which themes might have been popular and which might have predated the Gospels. But they cannot tell us if we have got back to the words and deeds of the historical Jesus because we do not have enough independent, early data.

Instead, it is better to think in general terms about establishing early themes and ideas that were most likely associated with Galilee and Judea around the time of the historical Jesus while accepting that we cannot know whether Jesus said or did what was attributed to him. For instance, the claim that Jesus predicted an imminent transformation of the world is most likely early. Already in the mid-first century, there were concerns that millenarian predictions were not being fulfilled (e.g., 1 Thessalonians 4–5) and by the second century there were explanations given to why earlier predictions had not happened and reinterpretations of these predictions were provided (e.g., John 3.3–8; 21.20–23; 2 Peter 3.3–10). It seems likely, therefore, that early on there were authoritative predictions of imminent transformation of the world (e.g., Mark 1.15; 9.1) which generated such eschatological enthusiasm.

An emphasis on broader, early themes also forces us to think less about Jesus the Great Man and more about the broader social context of the movement associated with Jesus. It is for these reasons that I regularly use the term “Jesus movement” to describe the people responsible for the earliest traditions about Jesus, a framework which has the added benefit of highlighting the collective nature of, or support for, these ideas.

So, grounded in the approaches briefly outlined above, I want to give an outline of what we can say about the earliest ideas associated with Jesus, why this movement and these ideas emerged when and where they did, and how class interests are crucial for understanding the rise and continuation of this movement. I have, along with Robert Myles, provided a fuller argument in our recent book, Jesus: A Life in Class Conflict.

Jesus in Galilee and Judea

Jesus was from a small village in Galilee called Nazareth and likely a labourer of some kind. As he was growing up, there were urbanisation projects in Galilee which brought about some important changes to the life of Galileans. For instance, the nearby town of Sepphoris was rebuilt following an uprising and Tiberias was a newly built town named in honour of the Roman emperor, Tiberius. The urban elites extracted resources and surplus from the surrounding countryside and, in the case of Sepphoris, this included the village of Nazareth. The innovations in Galilee put greater demands on the peasantry and redirected key resources towards places like Sepphoris.

There has been an often-misguided discussion about the standard of living in Galilee at this time with scholars debating whether these changes provided lucrative employment opportunities for Galileans or impoverished them. The reality was more complex, however, and traditional ways of life were clearly changed. For a start, the first-century Jewish historian, Josephus, noted that in Tiberias there were people removed from their land while gifts of land given to others (Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 18.36–38).

There is discussion in the Gospels of the breakdown of households which likely comes from what was happening in Galilee (e.g., Mark 3.31–35; Matthew 10.34–36 paralleled in Luke 12.51–53 and Gospel of Thomas 16.1–4; Matthew 10.37, paralleled in Luke 14.26). It is striking that this tradition includes the idea of Jesus’ movement forming an alternative household. This was not to critique the ideas of the traditional family—this would not have worked well in an ancient agrarian setting—but instead familial language was the obvious communal language to mimic and address the breakdown of households.

There were established, if limited, vehicles for discontent and agitation in Galilee, as in so many pre-capitalist agrarian settings: banditry and millenarianism. Banditry ranged from targeting those thought to be responsible for exploitation through insurrectionism to basic gangsterism. Millenarianism offered a fantastical vision of transformed world to come and a promise of punishment for unjust rulers, elites, and their supporters.

Salome with the head of John the Baptist, by Caravaggio

Banditry and millenarianism were not mutually exclusive categories, not least from the perspective of the ruling class. Jesus’ likely mentor, John the Baptist, was a millenarian prophet, but the local ruler Herod Antipas took no risks when a large crowd of followers amassed in the wilderness and simply had John the Baptist killed as a violent insurrectionist.

Jesus’ fate would be similar as his movement likewise took the millenarian option, most famously expressed in predictions of the coming “kingdom of God” or “kingdom of heaven.” This phrase could equally be translated “empire of God” as it was the same language used of the Roman Empire. This was not an egalitarian vision of the future, as is sometimes romantically presented, not least on parts of the left. It was a hope of a supernatural intervention understood in the light of traditional peasant values and the Jewish scriptures—a widespread view which is also found in Josephus’ explanations of first-century popular millenarianism (Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 18.118).

The conceptualisation of a new world reflected peasant understandings of hierarchy, with a just king and a core group of elevated members who would have pride of place in a restored Israel, judging who was saved and who was damned. This expected Golden Age was conceptualised as a theocracy which would replace the Roman Empire and their puppet rulers, dispense justice, and ensure a bountiful existence for those saved.

With tongue only partly in cheek, we might demystify the phrase “kingdom/empire of God” further and think in terms of the “dictatorship of the peasantry,” that is an expectation of a transformed world that would be run in the interests of the peasantry—again a view which would have chimed with what we know about first-century popular millenarianism from (for instance) Josephus.

Jesus took on the role comparable to the more rebellious lower clergy of medieval Europe, namely mediating between the people and divine with his authority owing more to popular support than endorsement from the official religious channels. This direct access to divine authority allowed Jesus (and comparable figures like John the Baptist, to name the most famous) to challenge the current state of class relations.

The Jesus movement may not have been egalitarian in the strict sense, then, but it still envisaged a world turned upside-down. There is an early tradition of role reversals in the world to come (e.g., Mark 10.17–31; Luke 16.19–31) which stressed that poorer and non-elite sections of Jewish society at least were going to be among the beneficiaries and that those deemed rich would have to give up their property and wealth if they were to be saved.

In this respect, it is striking that Jesus was remembered as being criticised for associating with tax collectors and “sinners.” Beyond the Gospels, tax collectors had a reputation for being greedy and exploitative (e.g., Cicero, De Officiis 1.150; Josephus, Jewish War 2.287, 292; Mishnah Nedarim 3.4). “Sinners” likewise. Again, the popular (and even scholarly) myth that “sinners” was a derogatory term for the poor, marginalised, and downtrodden, and that nasty Pharisees criticised Jesus for associating with supposed undesirables, does not hold up.

Sinners are exploitative rich people

I have collected (and summarised in Jesus: A Life in Class Conflict) the common words for “sinners” in the relevant languages over a period of several centuries before and after the time of Jesus, and this research shows consistent and clear patterns. “Sinners” were deemed to be acting beyond Jewish law (or interpretations of Jewish law) and whenever socio-economic status is mentioned, it is always in relation to them being exploitative, rich people. The reason Jesus was criticised (or at least presented as such) was because these people were regularly understood to be cruel, lawless exploiters beyond redemption.

The rich and the powerful, by Ignacia Ruiz

Whether the Jesus movement’s mission to the rich was successful is moot, but it was part of extended social network allowing the movement to survive and spread. For a start, connections with elite women, or women with resources, seems to have been important for funding this sometime itinerant movement (see, e.g., Mark 15.40–41; Luke 8.1–3). Tax collectors and fishermen are noted occupations in the Gospels, and this is no surprise—as John Kloppenborg points out, tax collectors also interacted with fishing networks on the “Sea” of Galilee through taxation on catches and on boats which doubled up as transportation services outside busy periods.

Fishermen, we might add, were also a culturally credible, and economically crucial, group closely associated with the Jesus movement. These networks provided scope for the message to spread beyond the even more localised networks in Galilee.

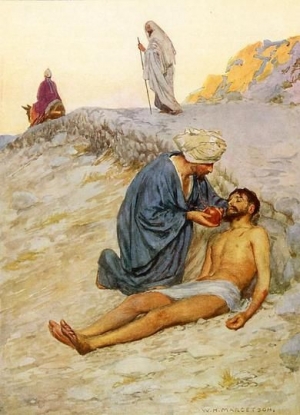

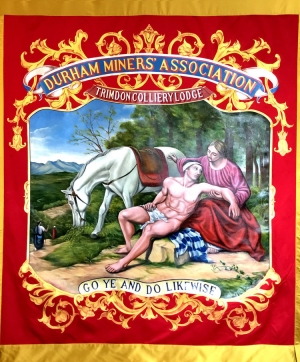

The Jesus movement maintained its social credibility by emphasising the importance of traditional peasant values, strict morality, group discipline, criticism of elite values, and respectable interpretation of Jewish scriptures. It is telling that debates over the interpretation of Sabbath and purity laws tally with rural and non-elite interests. This included acceptance of plucking grain on the edges of fields on the Sabbath for sustenance (Mark 2.23–28) and downplaying the maintenance of ritual purity laws in all areas of everyday life (Mark 7.1–23; Matthew 23.23, paralleled in Luke 11.42; Matthew 23.25–28, paralleled in Luke 11.39–44; Luke 10.29-37)—a position that was associated with (among others) rural workers, some of whom were liable to become regularly impure through their work. Collectively, such interpretations of Jewish scriptures were an attempt to provide a dignified alternative amidst the upheavals in Galilee.

With John the Baptist executed, it is likely that the Jesus movement knew the risks of collective organising. They drew on Jewish traditions of martyrdom, some recounted annually at the festival of Hanukkah, which were understood as sign of strength rather than weakness and believed to play a role in the expected transformation of the world (e.g., Mark 10.35–45; Luke 13.31–35, paralleled in Matthew 23.37–39; compare: Daniel 11.35; 2 Maccabees 7; 4 Maccabees 7.20–22; Josephus, Jewish War 1.650; Lives of the Prophets; Ascension of Isaiah 1–5).

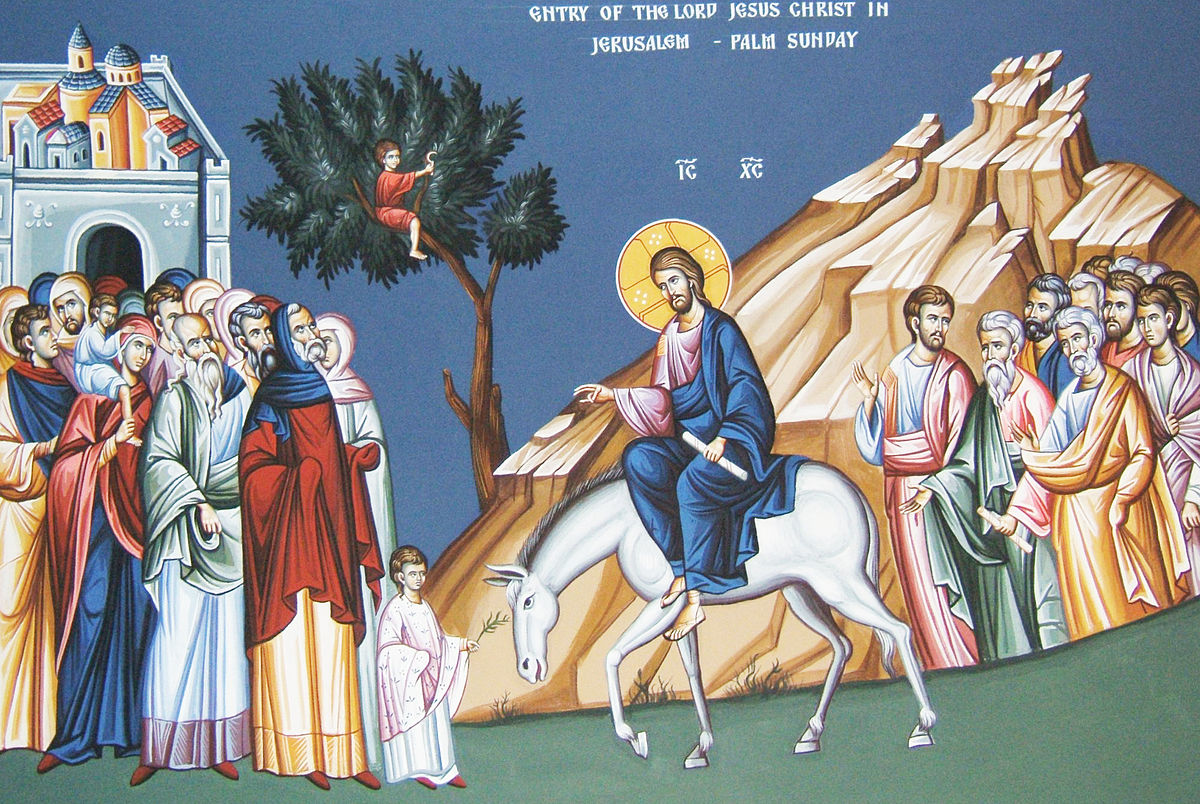

This all came to a head in a final visit to Jerusalem at Passover. Passover was always tense, not least because it was a festival commemorating and anticipating freedom from subjugation. Indeed, it is possible that Jesus interpretated the Passover meal in terms of his expected execution and the imminent defeat of the Roman Empire through supernatural intervention (e.g., Mark 14.22–25).

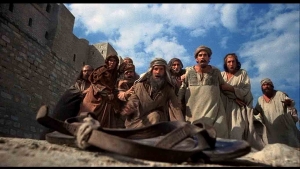

Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple, by El Greco

In a packed Jerusalem, the authorities were wary of a riot and the potentially volatile crowds (some of whom appear to have had sympathies with the Jesus movement) were aware of the fate of rioters. At the Temple in Jerusalem, Jesus appears to have overturned the money changers and dove-sellers in what was likely an attack on a religious-economic system some Jews thought to be corrupt (Mark 11.15–18). The Temple was a prominent part of the tributary system in Judea which meant attacking it publicly was a dangerous enough act, but at Passover, even more so.

This act led to the inevitable arrest of Jesus. The only real difficulty from the perspective of the authorities was how to deal with the problem without causing a riot. Jesus was eventually arrested and executed on a Roman cross as a bandit or violent insurrectionist—effectively for the same reason other Jewish millenarians like John the Baptist and others were.

The typical fate of a victim of crucifixion was to be hung out as a warning and then slung in a pit. Some scholars have argued that this was the fate of Jesus. This is certainly possible, but it is also possible that there is some truth behind the story that Jesus was buried in the family tomb of Joseph of Arimathea. Joseph was known to be wealthy and this burial, coupled with Jesus’ known reputation as an interpreter of Jewish scriptures and a respected millenarian prophet, may have been a result of the mission to the rich.

What Happened Next

Reconstructing Jesus’ burial is speculative but, curiously, one area which is less so is that of sightings of the resurrected Jesus. From the mid-first century, Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians (1 Corinthians 15.3–8) recalls how Jesus appeared to his followers or would-be followers, including Paul himself. This is an unambiguously early tradition associated with people Paul knew and part of a common enough cross-cultural phenomenon of people claiming to have experienced visions of some sort. The basic point is that some people believed that Jesus-the-martyr had been vindicated and accordingly elevated into some sort of post-mortem existence.

Certainly, claims to resurrection were important for the earliest followers of Jesus after his death and for the development of Christian theology. Nevertheless, such beliefs were not unusual for the time and are not enough to explain why the movement survived and spread. It is a common feature of emerging religious (and political) movements to grow through social networks (e.g., family, friends, workplace, etc.) and this applies to the emergence of Christianity. We have already seen how the movement began to grow beyond the Galilean peasantry through fishing communities and tax collectors, as well as through women with some resources and status.

This process continued on a wider scale across the Mediterranean world. Households, associations, and workplaces continued to be important points of contact for the spread into urban centres with adherents from a range of backgrounds. Again, women as heads of household played an important role (see, e.g., Romans 16.1–2; 1 Corinthians 1.11; Colossians 4.15; Acts 12.12–17; 16.14–15). Women or girls would typically marry older men in the ancient world and when the husband died the wife might run the household. We also know that some women had the time and means to develop an interest in philosophical ideas and there is evidence of non-Jewish women in the eastern Mediterranean interested in Judaism (e.g., Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 18.81–84; 20.35; Jewish War 2.560–61). This context provides some insight into the networks that were suitable for the spread of the Jesus movement in the years after Jesus’ death.

Ruins of the Ancient Synagogue at Bar'am

Non-Jews interested in Judaism were important for the movement to attract more non-Jewish adherents. Jewish gatherings or synagogues were found throughout the Roman Empire and were unsurprisingly important points of contact for emergent Christianity. But synagogues also attracted non-Jews interested (in varying degrees) to Judaism. The Jesus movement already provided an ideological justification for incorporation of such people: the inclusion of “sinners.” The term “sinners” was also a common shorthand for “non-Jews” and was so because non-Jews in some sources were stereotypically associated with the conquering nations who might plunder Israel and were, by default, beyond Jewish law (see, e.g., among many references: Psalm 9.17; Tobit 13.6; 1 Maccabees 1.10; 2.45–48; Wisdom of Solomon 19.13; Psalms of Solomon 1.1; 2.11; 1 Enoch 99.6–7; 104.7–9; Galatians 2.15).

With these connections in place, we can understand why the movement rapidly had to deal with questions about its own identity: was this still a Jewish movement or something else? There were plenty of competing influences on new adherents. If they were in a synagogue, we can reasonably expect that they would have behaved in a way that did not offend their Jewish hosts. If they were in a trade association, in a workplace, in the army, or with extended family, they might behave quite differently where there were different social expectations, such as eating pork, eating food sacrificed to other gods, or working on the Sabbath.

In the case of men, there was the problem of circumcision and there were debates as to whether it was required for a male convert to become a Jew (see, e.g., Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.34–48; Pirqe de Rabbi Eliezer 10; compare also Jewish Antiquities 13.257–58, 318, and 15.253–54). In the case of families with competing external loyalties, this led to divisions within families (e.g., 1 Corinthians 7.12–16). In the case of enslaved household members, this would have involved compulsory conversion irrespective of personal beliefs (see, e.g., Exodus 12.48; Digesta 48.8.11).

Gatherings of the emerging Christian movement were a mix of people from not just different classes but from different ethnic backgrounds. Against this backdrop, figures like Paul emerged to provide theological solutions for pre-existing social and material problems involved in integration. For Paul (e.g., Romans 1–4; Galatians), circumcision and observance of Jewish law were no longer required (for non-Jews at least) and, for all the controversies Paul faced, this turned out to be a decisive move in the long-term development of Christianity as a non-Jewish religion.

Scribal or administrative roles were also necessary in the mediation (and thus spread) of the movement beyond its localised and parochial Galilean peasant setting. This process likely involved village scribes and, as the movement spread, the ongoing writing and dissemination of texts almost certainly involved slave labour. At this point, slavery was an assumed mode of production for the emergent Christian movement and was unlikely to be challenged in the present because the inherited millenarianism was both a fantastical resolution to social injustices and based on existing hierarchical models of social stratification.

When Paul claimed, “There is no longer Jew or Greek [i.e., non-Jew/gentile], there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3.28), he did not mean the end of slavery or class exploitation, any more than he meant the end of male and female roles in everyday life. Rather, this was a justification of the reality of the social mix of people now involved in the movement.

From about the end of the first century, the Gospel of John represented an important development in Christianizing the movement. As noted above, John’s Gospel argued that Jesus claimed to be equal with God. However, the Gospel tellingly presents Jesus in opposition to “the Jews” who tried to kill Jesus for making such claims (John 5.18; 10.30–33). Whatever the nuances in the original context of the dispute between the writers of John’s Gospel and their Jewish opponents, these stories were easily adapted into negative statements about Jews collectively and their alleged violent opposition to Christianity. This represented a step toward identifying Christian understandings of God as distinctly different from Jewish ones, as well as laying the foundation for later anti-Judaism and antisemitism.

Within three centuries, Christianity was sufficiently embedded in the Roman Empire to become its official religion. The longer-term developments in empire building, roads, transportation, and communication that had taken place in the ancient world over centuries were conducive to the spread of ideas of an overarching God covering—and justifying rule over—a range of peoples from different social and ethnic backgrounds. The Christian version of this understanding was, in a less dramatic way, the expected realisation of the millennial and imperial dreams of Jesus and now intensified by Paul:

‘at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father’ (Philippians 2.10–11).

It was not difficult for the Roman Empire to co-opt such ideas for its imperial ideology.

Marxism, Jesus, and Christian Origins

A trajectory can be traced from the theocratic millenarianism of the Jesus movement in rural Galilee to the religion of the Roman Empire, and then onto Christianity as the ideological justification for feudal relations in Europe followed by bourgeois power. But the movement associated with the historical Jesus had obvious differences from what followed. It was the product of shifting patterns of exploitation and land displacement in Galilee, acting in the interests of the peasantry and damning the rich who did not give up their wealth.

What Marx famously said of religion in the introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right applies here: this was “the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering.” These ideas did not disappear from Christianity. As it became the official religion of the Roman Empire and then feudal Christendom, so it also provided the main language of resistance, with some of this later absorbed into socialist thinking.

Historical materialist accounts relating to Christianity are prominent enough in scholarship. But the further back we go, and the closer to the historical Jesus we get, Marxist understandings become less prominent. What is now needed is a new generation of critical Marxist historians to develop a thoroughgoing account of the emergence, development, and influence of the Jesus movement and earliest Christianity, and locate their place in a historical materialist account of the past and lingering influences in the present, whether reactionary or progressive.

To paraphrase Marx, this must be a ruthless criticism of Christian origins, unafraid of both the results it reaches and the conflict it provokes. It will involve dismantling some of the romantic, anachronistic but ongoing myths about Jesus the hippy, Jesus the liberal, Jesus the entrepreneur, Jesus the conservative—but also Jesus the socialist and feminist somehow ahead of his time, if only to understand what kinds of class relations exist in different times and places.

This historical endeavour will understand the emergence of a movement in Jesus’ name as one which takes seriously ancient modes of production, material conditions and changes of his time, and the accompanying class struggles, no matter how alien they may seem today.