'Prayers to the environment': Jane Burn on nature, her writing, her life - and her new book

Fran Lock interviews Jane Burn, author of Yan, Tan, Tether (Indigo Dreams Press, 2020)

Fran: Thank you so much for agreeing to answer these few questions about your latest collection of poems and illustrations, Yan, Tan, Tether. I’m really excited to do this interview with you, firstly because both the poetry and their companion images speak to my own interest in mediaeval beast poems, but more importantly because a better understanding of how we relate to the animal others in our midst has never been more pressing or more necessary.

I don’t know if you’d agree, but I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable about the way art has traditionally made use of the animal world. I was reading an old Guardian interview with Kathleen Jamie the other day, where she talks about nature writing having been ‘colonised’ by ‘middle-class white men’, who produce this decidedly anthropocentric poetry where the animal is only meaningful in respect to the sensations, emotions or ideas it produces in a privileged human observer. One of the most admirable – and I want to say radical – aspects of Yan, Tan, Tether, is the kind of mutuality you evoke between your human and animal speakers. Your animal subjects aren’t ciphers for human experience, and your human observers are attentive and respectful to the otherness of the animal. I want to ask first how conscious you were when putting this collection together of writing back to or against that middle-class white male model of contemporary nature writing, and what parallel traditions you might have been drawing from?

Jane: Have you ever sat, quiet and frozen absolutely still and held your breath in order to see how close a bird will come to you? You hardly dare move as this amazing, fragile being (that you could crush with one hand) weighs you up. You become aware of every twitch, every hop and flicker of the bird. You see so much expression written on those tiny beads of eye. You notice each little feather in such unexpected detail. You try with all your might to project to the bird how safe you are, how you would never dream of hurting it. It watches you, head cocked, every mite of it poised to fly away at a split second’s notice. You have absolutely no idea what that bird is thinking, or whether it considers you at all beyond a brief curiosity. It measures you quickly – friend or foe? The quieter you stand, the less ‘human’ you are, the nearer it will come.

A couple of weeks ago, I stood just like this in my front garden, statue-still, watching the birds on the bird table from a safe distance. The sparrows came and went individually – blue tits landed on the peanuts in twos and threes. A wood pigeon made an ungainly crash-landing on the fence. A robin flurried among them and drove them away. I thought about how they have their own society, their own complex rules, their own desires and needs, their own individual songs.

In a moment that was over before I had the chance to really register it, a sparrow suddenly landed on my shoulder. After a brief second, the noise of its wings as it flew away sounded in my stunned ear. In this moment, it was like a meeting of two universes. It was a rare connection between our different worlds. It wasn’t a Disney Snow White moment – the birds weren’t there to accentuate my sweetness, to add their backing vocals to my virginal voice. They weren’t there to light upon my delicate, unblemished hand and thrall at my young, doe-eyed beauty (doe-eyed – don’t get me started on that one). They certainly weren’t there to help with the housework. In fact, you could probably go on a lot longer about Disney and his ‘birds’, like when Sleeping Beauty, with her thick tumble of blonde curls, her 18” waist and miniscule feet wanders through a wood spangled with fawning blue and canary yellow songbirds bemoaning her lack of a man.

I am interested in a different kind of ‘magic’. Sometimes I think women have only been allowed nature if it is a foil to keep us in our place. I remember us watching and re-watching our VHS copy of Legend, way back in the 80’s. I loved the film so much but today I am irked by the scenes that emphasize that those beautiful unicorns can only be touched by pure maidens – white clad virgins who reach with awe towards that horn. I think too about how it was a woman’s fault that the wonderful world there was plunged into darkness – ’twas Beauty led the Beast to bay.

By way of a follow up question, I’m aware that there’s this easy and rather patronising assumption of affinity between the feminine and the wild or rural, which I think has been used to marginalise or dismiss women’s contribution to the poetry of the natural world, particularly working-class women, who, in any case, never receive the same critical attention as their male counterparts. Something I really admire about this book is that is shows us the wonder in the ordinary, in the ‘scary’ or the ‘slimy’ too. There’s both reverence for humble things and pity for the damaged, yet not in a sentimental way that softens their rough edges. This feels like such a powerful middle-finger to both the Disnification of nature, and to the arbitrary and shallow distinctions people make about what (and who) is or isn’t worthy of care. One of my favourite illustrations in the whole collection is the slug in ‘Mollusc Song’ wrapped with a speech scroll reading ‘still I find a way to dance’. I wonder to what extend you see Yan, Tan, Tether as a feminist collection? And do you think being a working-class woman has coloured the reception of your work generally?

Animals are not meant as a metaphor for ‘ideal femininity’, are not there to accentuate our innocence, beauty, delicacy and sweetness. Most of them would avoid us absolutely I am sure, if they could. They dig, bite, kill, screech, chase and catch. They shit and fuck in the open, having been spared our human notions of shame. Think of the fear men had in the past of strong women and their affinity with animals. Got a cat? You’re a witch. Even the thought that a woman might somehow transform into a hare was enough to burn them at the stake.

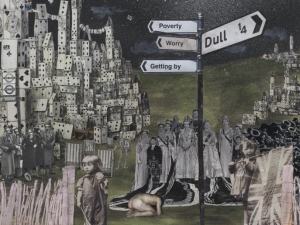

Part of my working-class make up is that I live in terror of my own ideas of intelligence. The overwhelming attitude that nobody is going to be interested in you. It’s alright telling me that it’s all in my head, or my ideas of class are my own, or I’m just paranoid, or I am just silly, or it doesn’t exist. My schooling was crappy and I had no idea of the opportunities out there. My parents had no idea of the opportunities out there, not really. I was too shy to say boo for too many years. I am a victim of bullying and abuse. I have been a physical and metaphorical punchbag for so long that my voice was knocked out of me. I have no confidence with anything that requires me to sound like I know what the hell I’m talking about, so please excuse the way I tiptoe around these questions and probably fail to answer any of them at all properly.

Of course I read books about the characters’ varied jobs and lives but they were the lives of other people, not some irrelevant lump, stuck in a nowhere village, grasping books from jumble sales and thanking the stars for the local library. Look at the way they have closed libraries down. What are the children like me going to do now? How are they meant to cobble their own education together now? I have given up feeling sorry for myself but have remained angry. I don’t fit into anyone’s box. My writing doesn’t fit into anyone’s box. I feel I have so much more to prove. I feel as if I am always fighting and that gets very tiring, sometimes. This feeling has been with me so long now, it’s not something I can shake. Call me chippy, go on. I’ve been called it before. I often wonder if I can feel that ceiling above me – that no matter what I write, I have got as far as I am ever going to go.

I want to move away from my heavy-handed political reading of your work now, because I feel like I’m in danger of sucking the joy from what is absolutely a rich, strange, and vivacious book. Instead, I’d love to ask you about the texture and tactile pleasure of your language. There’s a particularity and exactness of phrase in this work that feels intuitive, lived and local. It reminds me of John Clare, who is perhaps my own favourite nature poet. Could you tell me to what extent do the poems in this collection grew out of your own relationship to the landscape and animals around you?

I am terrified of grammar and punctuation. Perhaps that is why I love to free myself within other voices, voices that free me from the idea of restraint. I love words – I am a complete and utter collector of words. Because I don’t belong anywhere, I can belong everywhere (if that makes sense). I can hop and jump through districts and dialects. I make up words of my own and this comes to me easily because maybe I never learned the rules in the first place. To grow up an outsider even in your own community (because you are weird) was not lonely for me. I didn’t want their company. My mother had a hatred of seeing me sitting in some corner reading, or scribbling and sketching onto envelopes, cereal packet backs, etc and would physically turf me out.

I would wander miles on my own – this was something I was used to, right from reception class where I was expected to walk home from school on my own. It was always horses that I sought. I was a master of waiting – it was always worth the wait when they came to the fence and they always tolerated me. Let me touch them. My comfort was being reflected in their eyes. To many, the main thing with horses is riding upon their backs. What about getting to know them first? A big animal that could kick you into next week can hold you with such gentleness in its heart.

At my saddest, I would dream of changing into something else. I galloped round the garden, leapt imaginary fences. I squatted in the garden watching the travelling of snails, pretended to be tiny as a ladybird in the grass. I think this is where the theme of transformation comes from. I have never managed to be at peace with myself as an adult either. I hate the way I look, that I can never be in control of what I am eating, or saying. I am taciturn, loud, inappropriate. I am lonely one moment and hate the idea of company the next. I make my world into a protective shell and feel comfortable within it. To imagine transforming into the purity of an animal’s soul is something that has always inspired me. If I held a mirror up to my own beloved horse’s face, he would do nothing more than shade it with his exhaled breath. A kitten sees its reflection and plays. I look in the mirror and recoil. Imagine the freedom of the sky! I feel it so strongly I get giddy. I root the soil with my fingers and it seems like I sense every molecule in it. I feel connected, unjudged.

I don’t ‘mean’ to write. I tried to describe it during an assessment last year – that it was a sort of rain that falls down all around me and in some places the words begin to string themselves together like beautiful beads. When the words are good, there is no better feeling. When the words are bad, I try my best to ride the waves. Either way, after one of these experiences, I have to race to the nearest writing equipment and put it onto paper. Maybe it’s like speaking in tongues – it’s not something you can control or help. Being possessed like this can be so uplifting yet so draining. There is no escape from it – yes, it has upsides and downsides but it is me and I couldn’t live without it, even if I knew how.

As a related question, I’m also curious about the mythic or folkloric qualities of the poems, qualities that are underscored by the beautiful companion illustrations. One of the things I love most about the book is that it brings into collision these two medieval forms: the book of hours, and the beast poem, so that there seem to be both Christian and pagan influences at work, both ancient and modern sources of inspiration. Could you talk a bit about the different influences and traditions that went into making the book? What was the impetus for the collection as a whole?

I believe that a lot of folklore and myth has sprung from similar places. When I was very young, I loved Greek and Roman stories. As I grew older, I read more and more. This is a place where nothing needs to be what it seems, where there is magic, where there is pleasure and pain, where people and animals intertwine. I was fascinated by creatures like the minotaur, and centaurs and harpies. The idea of two creatures living in one skin was always something that somehow comforted me and gave me hope. I felt much less alone and it felt natural to me to connect in this way.

I was raised a Methodist and yes, I have such fondness for those pared down, plainly painted chapels. My mother was a Catholic however and I had such a fascination and craving for rosary beads, statues of the Madonna, pictures of the Sacred Heart. This led to learning about iconography (especially Russian icons) and manuscript illumination. Every wire of my brain strums at the sight of them. To me, they are the epitome of faith, skill, patience and joy. They are unashamed celebrations. If you wanted to express your greatest love on paper, that would be the way. They are glorious and the book of hours takes everything to the next level. They are such staggeringly precious expressions of devotion. They are exquisite – raw and real with colour, fearless in their purpose.

I have often wondered, over the years what my faith is to me. I came to the conclusion that it has never been just one thing. It is the cobbling together of a lifetime of love – the greatest love of all being the natural world. If I had to choose one thing as my church, nature would be it. To make a sort of book of hours of my own, one that could also be enjoyed by others as part of their own ‘worship’, seemed a natural progression. I don’t think the poems would function so well without the illuminations. Both lend so much extra depth to the other and adding text to the pictures helps to connect them even more.

I’ll try to make these last questions a bit more practical and succinct: firstly, could you tell us a bit about the relationship between your painting and your poetry? Calling the images ‘illustrations’ almost seems wrong – let’s call them ‘illuminations’ instead in every sense – as they feel just as integral to the collection as a whole as the poems. Could you perhaps talk a little bit about the particular work each art form is doing? Does one form always precede the other?

I had these images in my head as I was writing the poems although I didn’t commit them to paper until after the poems were written. I wanted to wait until I was ready to give myself over to the production of them as a whole as it can be very distracting to have to keep packing up artwork or jump from one project to another. I knew I had a good number of them to produce – 23 in total (including the cover). The earliest poem in this collection was Froghopper, which was written in 2014, and the illuminations were produced through the winter of 2018. Just like an ancient monk, I set my table up with equipment and worked tirelessly on them and it was a pleasure to be able to give myself over to such an involving project. It was great to finally be able to set the images free from the confines of my head. The book was beautifully and sympathetically published by the wonderful Indigo Dreams in December 2019, so I guess it shows sometimes how long it can take a book to come to fruition.

The borders for the images were just as important as the images themselves, just as they are in original religious works. For me they also allowed me to include and acknowledge some of the other artworks I love – canal art, rosemaling, the decoration on vardos, folk art. These are the works that I love. You might not see much of it in galleries but they are beautiful to me. I felt I had to include references to these styles if I was going to remain true to my own heart.

Last of all, I’d love for you to tell us something about the animal friends and collaborators in your life, as it feels really appropriate that we give these important figures the final word.

These are the friends that I share my life with currently – my horse Orca and dogs Iggy and Patsy. Orca came to me from the Traveller community when I was 37 (I’m 48 now). He lived with a huge herd of mares and foals that roamed free on a massive acreage of grazing. I was told, simply, to go ahead and walk to find them and choose one. Many of the foals were friendly, some even bold, but it was the tiny red and white, peeping warily from behind his solid mother that instantly stole my heart. Each foal was completely unhandled and had been born in the field at the mercy of nature, as they would have been in the wild.

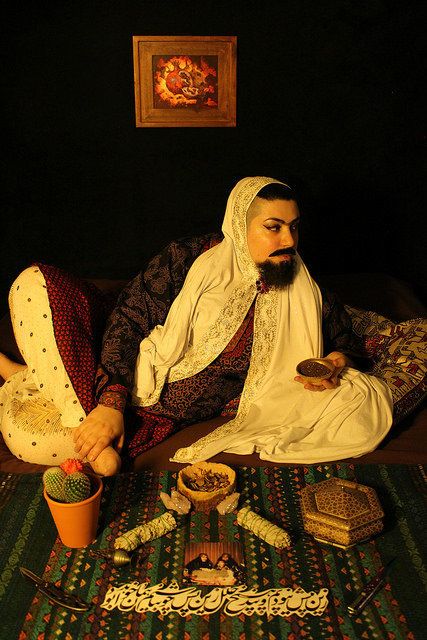

Orca would come nowhere near me. I visited the field three times a week for six weeks and as you can see from one of the pictures, I spent the time pretending to be a horse as much as possible. I stayed low so I wouldn’t tower over him. I kept my hands to myself – what would have been the point of trying to forcibly catch a wild creature in a 50 acre field? For four weeks, he came closer and closer. Curiosity brought him to me but he kept a safe distance between us. Weeks five and six brought with them touch and trust. He is twelve this summer and I truly believe our souls have become inseparable.

Iggy and Patsy are Jack Russells, and couldn’t be more true to type if they tried. One of my friends that knows them well says they ought to have their own TV series! Iggy came from someone who bred them as ‘foxing dogs’ for the hunt. It is a victory that he lives a completely different life with us. They are 9 and 8 years old and show no signs of slowing down. I could say that they are wilful, stubborn, vociferous, destructive, escapologist tearaways but that would be me projecting my own humanity on them. They are just 100% themselves, always filthy from digging and smelly from rolling. They love and protect us with a passion and we love them right back, though they are quick (especially little Patsy) so watch your fingers!

I guess when it comes to the wonderful creatures we share our world with, I have found that while you can learn some secrets from them, they teach me so much more about myself. They give me a voice that I use with confidence. They free me from constraints of language. They never look at one another as a kingdom to be conquered. They just are.

Thank you so much for talking with me. I really hope that wasn’t awful!

I hope that I have managed to provide some of the answers to these questions at least. I hoped that people will read the book and be inspired to get out there and use each page to inspire their own ‘prayers’ to the environment. The more you learn to love it at its most fundamental, the more I hope we become conscious of how much we need to do in order to protect it. The small changes are as important as the big ones. If you know the value of insects, you might be more aware of where you place your feet, or might not get the bug spray out so readily. The more you love the birds, the more you might let your hedges alone so they can nest, the more you might offer them food when times are tough. The more you get out into the open, the more you might fall in with the natural order of the seasons. I hope this book manages to do that, even a little bit.

Jane's poems have appeared in many magazines including The Rialto, Strix, Butcher’s Dog and Under the Radar, and anthologies from publishers such as Seren and The Emma Press. Since 2014 her poems have had success in 43 poetry competitions. Her pamphlets include Fat Around the Middle (Talking Pen, 2015) and Tongues of Fire (BLERoom, 2016).Her collections are noting more to it than bubbles (Indigo Dreams, 2016), This Game of Strangers (Wyrd Harvest Press, 2017, co-written with Bob Beagrie), One of These Dead Places (Culture Matters, 2017), Fleet, (Wyrd Harvest Press, 2018), Remnants (Knives Forks and Spoons Press, 2019, again written with Bob Beagrie), and the astonishing Yan, Tan, Tether (Indigo Dreams Press, 2020). Her poems have been nominated for the Forward and Pushcart prize. She is co-editor of Witches, Warriors and Workers (Culture Matters, 2020) and is an Associate Editor at Culture Matters.

Yan, Tan, Tether is published by Indigo Dreams Publishing, and is available to purchase here.