Your Solidarity be Praised: Review of 'The Orgreave Stations' by William Hershaw

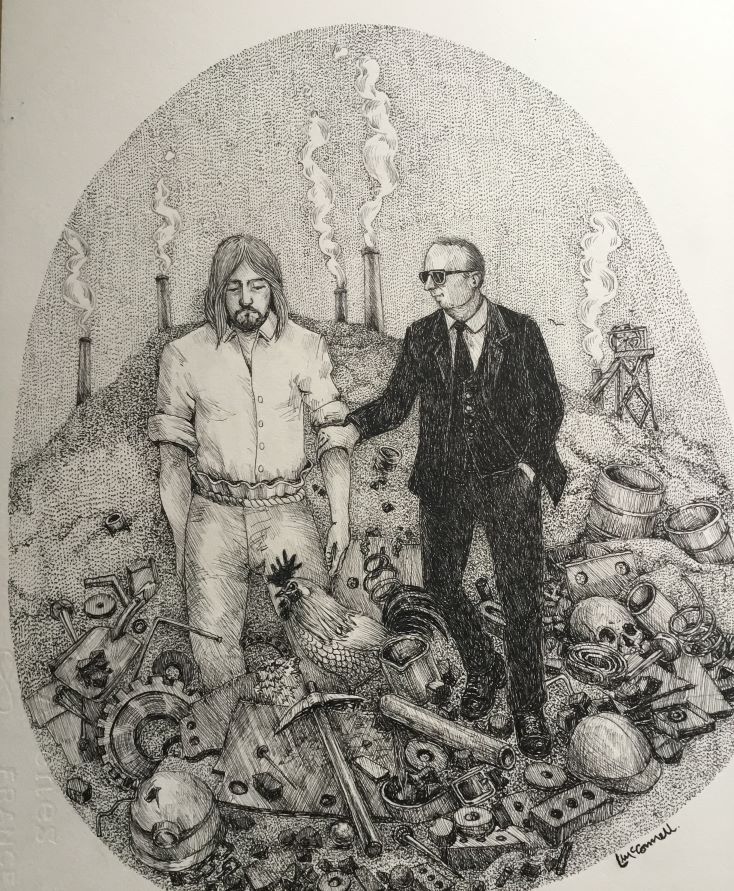

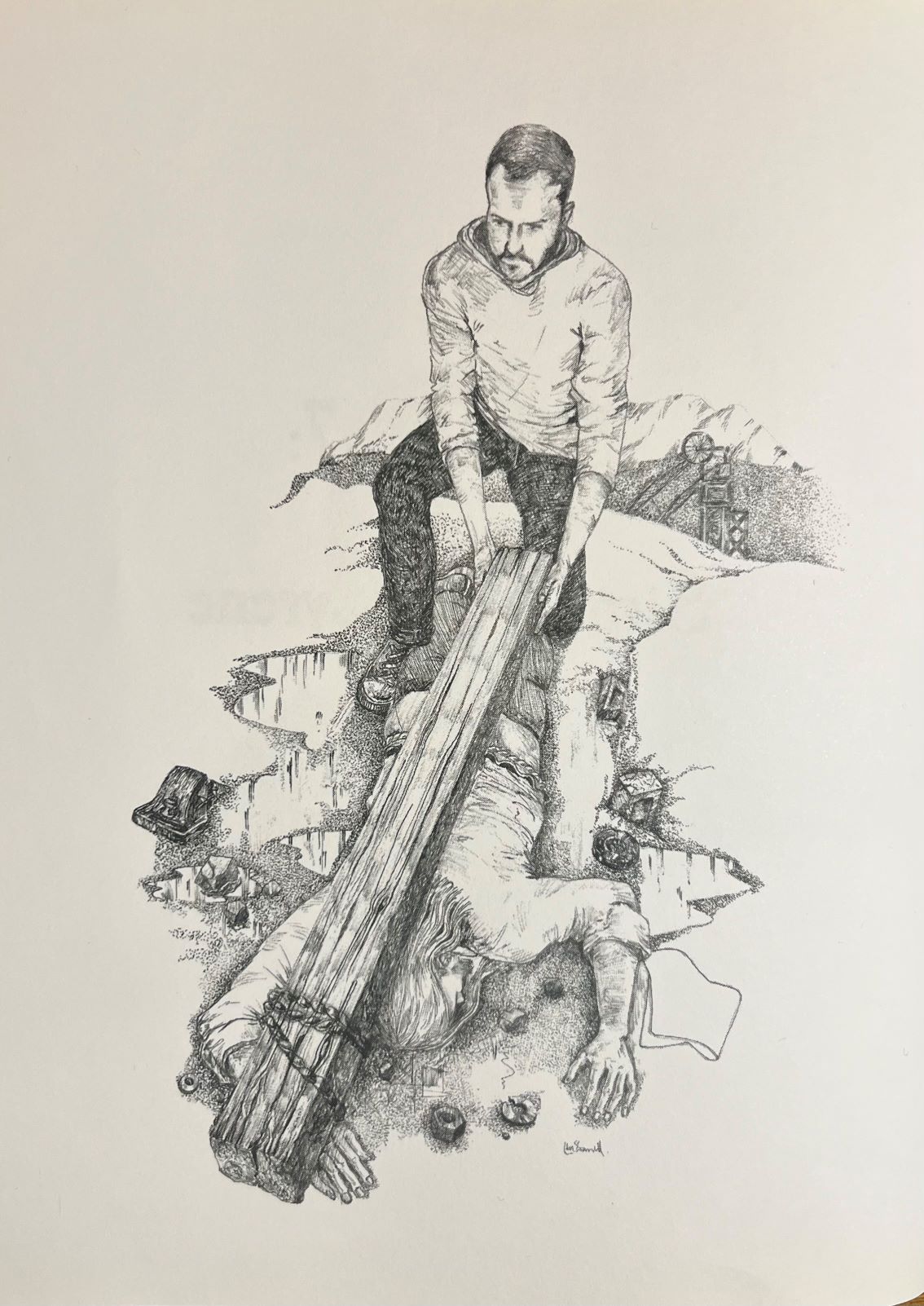

Jim Aitken reviews The Orgreave Stations by William Hershaw, illustrated by Les McConnell, some of whose images in the book accompany this review

‘The Orgreave Stations’ , published by Culture Matters, is the companion set of poems to his earlier work ‘The Sair Road’ (2018).

These earlier poems remain the finest poems written in Scots this century. These two books of poems complement each other in that they both use the Stations of the Cross as an organising structure, and in both books Jesus is a miner at the heart of the struggles in the Fife and South Yorkshire coalfields.

In both books Hershaw’s Jesus has been stripped of any hint of organised religion and there is no attempt at any point to proselytise for any religious faith. However, the Jesus we witness in Orgreave offers a religiosity that is remarkably similar to our understanding of what socialism should be. This Jesus would certainly be recognised by the Levellers, the Tolpuddle Martyrs and Keir Hardie. For Jesus of Orgreave ‘a Christian has to be a socialist.’

Yet the Stations remain purely structural and the appearance of Jesus as a miner serves to add a moral dimension to the story of Jesus handed down from the New Testament. Each Station uses an opening quote from the Gospels to add further context to the moral imperatives that Jesus of Orgreave proclaims.

Hershaw tells us in his Introduction that the use of the Stations and the role of Jesus as miner in the action is for the purpose of ‘symbolic religious imagery’ so that the poem can bring out ‘the full moral implications’ of what the destruction of a once proud industry meant.

The NUM – the 'enemy within'

Orgreave is 40 years old this year and for those miners who were there it must seem as if it was yesterday. It was a deeply traumatic event for the striking miners, to be met on one side by mounted police and on the other by police handling dogs to form the welcoming party. Orgreave, as Hershaw tells us, was ‘a pre-planned ambush.’ All the resources open to the British state were used to smash an irritant trade union that Thatcher at the time labelled ‘the enemy within.’

As well as the 14 Stations, Hershaw gives us a poem called Early Doors: At the Cross which precedes the Stations, and After Hours: Fear No More which comes after the Stations. Much of the poem is written in iambic pentameters, and Hershaw also uses a version of the sestina rhyme scheme (ABABCC) for his final poem. These poetic devices bring seriousness and gravitas to the sequence of poems, since the subject matter clearly demanded nothing less.

Station 1: The Road to Gethsemane Allotments

In the first Station Jesus calls his fellow miners ‘comrades’ and tells them to forgive those who seek their demise – ‘love the lousy lot.’ He also uses a couple of mining metaphors to labour this point. In one he says they should think on their own ‘slag heap of faults’ before they condemn others. And in another he asks them to make sure ‘their lives are pit-propped with love.’

While love remains the essence of the Christian message, it is also the basis of socialism. People, after all, become socialists because they care about others. A genuine socialist society would be one without hatred or division and the Jesus of Orgreave gets himself into deep trouble for preaching such a gospel of love.

Station 4: Big Pete

Jesus is duly arrested – ‘You’re lifted, Trotsky – in the fucking van’ and he is sent to jail. Jesus’ comrade, Big Pete, is shown to have his doubts as he seems to fall victim to what the right-wing press are saying, ‘The papers say that Thatcher will not turn.’ And he worries about the fact ‘There’s even some in Labour who agree.’ The then Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, now an unelected Lord, argued at the time for a ballot just as the Tory press told him to do. It has ever been thus with Labour, just as it is today with Starmer praising Thatcher and saying he will stick to Tory spending plans if elected, so that nothing will really change. The poor, marginalised and oppressed will remain unloved.

Station 5: Judged by Pilate

In Station 5 Jesus is judged by a smarmy Pilate who tells him, ‘Instead of helping losers, help yourself.’ Pilate recognises the strengths that Jesus has and asks him to come on board – ‘there’s room for those like you.’ Jesus can even become ‘a stakeholder in days to come.’ Jesus of Orgreave stands firm but these lines make us think about all the former Labour MPs and trade union leaders who have taken ermine, becoming so-called stakeholders in a system that continually exploits others at home and abroad.

After the brutal battle at Orgreave where the police ‘Brought batons down upon unfended heads, and sent dogs on the miners and called them ‘commie scum’, the action changes to an earlier time. Jesus was once the Safety Rep., approaching the pit manager to tell him about poor ventilation down the pit. He gets nowhere and is told by the boss, ‘I’ve seen your sort/ Out to create bother, always complain.’ In these short but prescient comments we can think of other miscarriages of justice – Ballymurphy and Bloody Sunday, Hillsborough and Grenfell, Windrush, the Post Office, the blood transfusion scandal, and many more besides. Bosses are especially chosen because they can be relied upon to put Caesar first.

The case of Paula Vennells, the former CEO at the Post Office, is an excellent example in recent times. It makes the comment of Hershaw that a Christian has to be a socialist somewhat ironic in her case – at the time she was CEO at the Post Office she also served as an Anglican priest. The Christian message is to love one another, and she obviously loved the Caesar she served more than the sub-postmasters beneath her.

The solidarity of the miners

Also, in another time Jesus recalls when he was saved by Simon of Cyrene after he slipped. Together they managed to lift a pit prop and the message here was,’ When they both worked as one, their load was light.’ These ‘other’ sections enable Hershaw to follow the original Stations but also allow him to show us the importance of solidarity. The miners were a workforce defined by their solidarity due to the nature of the job underneath the earth.

Station 8: Simon of Cyrene

That solidarity was dangerous when it was expressed above ground, when miners demanded better wages and conditions and were prepared to strike to save their jobs and their communities. As Shelley said in those famous lines ‘Ye are many – they are few’: working together workers can change the world, they can inherit it. The Pilates, however, seek only to divide worker from worker and in this they are aided by a class-compliant press and media.

Station 9: The Women

Similarly, in following the original Stations, Hershaw can make important mention of the work done by the wives and partners of miners during their year-long struggle. For him the Government was, ’Furious at your will to make ends meet.’ Their contribution must never be forgotten. Just like the faithfulness and loyalty of women like Mary Magdalene in the Gospels, it was the selflessness of the women against pit closures that shamed the ‘shallow lives’ of the Government and of all who supported them.

The crucifixion of Jesus is brought about through a pit accident; this recalls the thousands of fatal pit accidents that happened to miners down the years. Many of these accidents, of course, could have been prevented had bosses acted on advice given by Safety Reps and others. The miners of yesteryear are in fact no different to the football fans at Hillsborough, the sub-postmasters or the residents of Grenfell – all are sacrificed on the altar of Caesar.

Orgreave was our bloody Calvary

In Station 12 Jesus is on the cross, and he speaks to his mother. This speech is essentially what has happened after Orgreave and the Miners’ Strike of 1984-5. The victory of deep reaction has brought ‘Cultural and material poverty.’ It has brought the rejection that Society exists and all ‘To serve a selfish ideology.’ And this has been achieved through the violence of the state as their ‘dogs of war’ were used to attack ‘its own helpless folk… unleashed on communities.’ Universal Credit, homelessness (a lifestyle choice, according to Suella Braverman), zero hours contracts, student fees, drink and drug addiction, denial of the right to strike or protest and so much more besides – all these things flow from what happened after the Battle of Orgreave and the defeat of the strike.

Station 10: The Crucifixion

And yet, in the immediate post-war world there was hope for the working class. Jesus, we are told, ‘was born in a post-war dream/Jesus was born in a housing scheme.’ At that time, he had been born ‘with the highest of hopes.’ The defeat for the miners at Orgreave has given rise to a lived nightmare now for many. For this reason, Hershaw says, ‘Orgreave was our bloody Calvary.’

In Station 14 Jesus has died and there is an inquest into his tragic death; a death like so many miners before him. Hershaw mentions the names of Joe Green and Davie Jones, two miners who died during the strike while picketing to save their jobs, their communities and their class. Hershaw gives a telling line when he says, ‘Profit’s never mentioned at an inquest.’ How sickeningly accurate this line is.

The question now, of course, is will there be a resurrection for the working class? Hershaw offers two differing outcomes. In the pre-Station poem Early Doors: At the Cross he muses that ‘a new Happyland will come.’ But at the end of the Stations in After Hours: Fear no more he looks back on the great struggle of the miners to say, ‘May all your struggles now be past/ All souls like coal must turn to ash.’ While the earlier quote of a new Happyland sounds promising, the latter one suggests the opposite. Hershaw is being deliberately ambiguous because we do not know what will happen in the future. He is not saying we will be saved by believing in him though he does say, ‘Your solidarity be praised.’ Until that solidarity grows and people begin to realise that the state in which they live is geared only to the few and not the many, then a Happyland will come – but if this is not realised, then it will all turn to ash.

The Orgreave Stations is a profound reminder of how great the stakes are. The heroic struggle of the miners has to be remembered and celebrated precisely because it tells us about the need for solidarity. At the same time Hershaw’s Orgreave Stations makes us realise how he has lifted the poetic bar to a higher level by invoking the figure of Jesus the miner. This Jesus preaches socialism and his creed is dangerous to the ruling classes. The message of the New Testament is remarkably similar in that both creeds place love at the heart of their message.

Marxism is about political love

In a recent article in The London Review of Books (25th April) by Terry Eagleton (republished by Culture Matters here) called ‘Where does culture come from?’ he discusses the issue of ‘clashing self-fulfilments’ which he resolves by reference to Marx. Marx, he tells us, gives the name ‘communism’ to what Eagleton calls ‘reciprocal self-realisation.’ He then goes further and quotes from The Communist Manifesto – ‘the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.’

This is the high moral ground upon which any socialist or communist society should be based. No-one is excluded or victimised in such a society. There is recognition that we are all one body. Eagleton comments further:

When the fulfilment of one individual is the ground or condition of the fulfilment of another, and vice versa, we call this love. Marxism is about political love.

This is precisely what Hershaw is saying in The Orgreave Stations. Jesus of Orgreave embodies this kind of political love through his solidarity with the miners. This solidarity, of course, extends to everyone who wishes a better, fairer society, even to those who do not wish it. Such generosity is unthinkable in a class-based society where a ruling class decides on who the winners and losers will be.

In Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme, we see something similar when he says, ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.’ Comments like this had been around in the early days of the socialist movement and Marx simply refined it. However, a remarkably similar comment can be found in Acts of the Apostles where the lifestyle of the community of believers in Jerusalem is described as ‘communal.’ This meant that no-one retained any individual possession of goods – ‘distribution was made unto every man according as he had need.’

The Jesus of the New Testament and the Jesus of Orgreave recognise this communality. This is what makes them dangerous, precisely because their views challenge the vested interests of the few. Socialism is the higher creed in terms of morality since it represents sharing, fairness, kindness and care. These are lethal values for those who represent greed, selfishness, expropriation and exploitation.

Jesus of Orgreave, Grenfell, Windrush and Hillsborough

The Orgreave Stations expresses a high moral level, a socialism that stands as the antidote to all the profanities in our late capitalist world. It should also be remembered that when we consider the Stations of Jesus of Orgreave, we are also talking about his Passion, the short final period before his death. The Passion comes from the Latin patior meaning to suffer, bear, endure. That is what the miners did at Orgreave and throughout their strike. That is also what the working class continues to do. Jesus of Orgreave is also Jesus of Grenfell, Jesus of Windrush, Jesus of Hillsborough, of Ballymurphy and the Bogside and of the sub-postmasters.

Hershaw’s text makes us think about the renewal, or the resurrection, of socialist ideas and practices. Such is the power and the implications of these poems. They make us return to source, to the Christian values that set out to change the world. This poem makes us think of the words of Nikolai Ostrovsky:

Man’s dearest possession is life. It is given to him but once, and he must live it so as to feel no torturing regrets for wasted years, never know the burning shame of a mean and petty past; so live that, dying, he might say: all my life, all my strength were given to the finest cause in all the world – the fight for the liberation of mankind.

Jesus of Orgreave has no burning shame or torturing regrets. He sought the liberation of mankind and he did so without the baggage of any denominational dogmatics. His story lives as the story of the class he came from lives on. It has to, after all, since it remains the only hope for humanity and for our world.

Hershaw’s poem has been blessed by wonderful illustrations, by Les McConnell, some of which illustrate this review. They not only enhance the pages of the text but give it an updated twist, by illustrating ordinary people who are recognisable and relevant to the period of the strike. The artistic solidarity of the poet and his illustrator could be said to be a match made in heaven.

The Orgreave Stations is available here. There will be a launch of the book at a memorial event on Saturday 15th June, at 2pm at the Willie Clarke Centre, Lochore, Fife.