'The future of art hangs on the future of civilisation': The Artists' International and the Spanish Civil War

Christine Lindey looks at the role of the Artists International Association in supporting the cause of the Spanish Republic.

The early 20th century’s momentous upheavals politicised many people and artists were no exception. The mechanised carnage of the First World War, the 1920s Hunger Marches, the increased immiseration caused by the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the concurrent rise of fascism galvanised the left’s calls for peace and social justice.

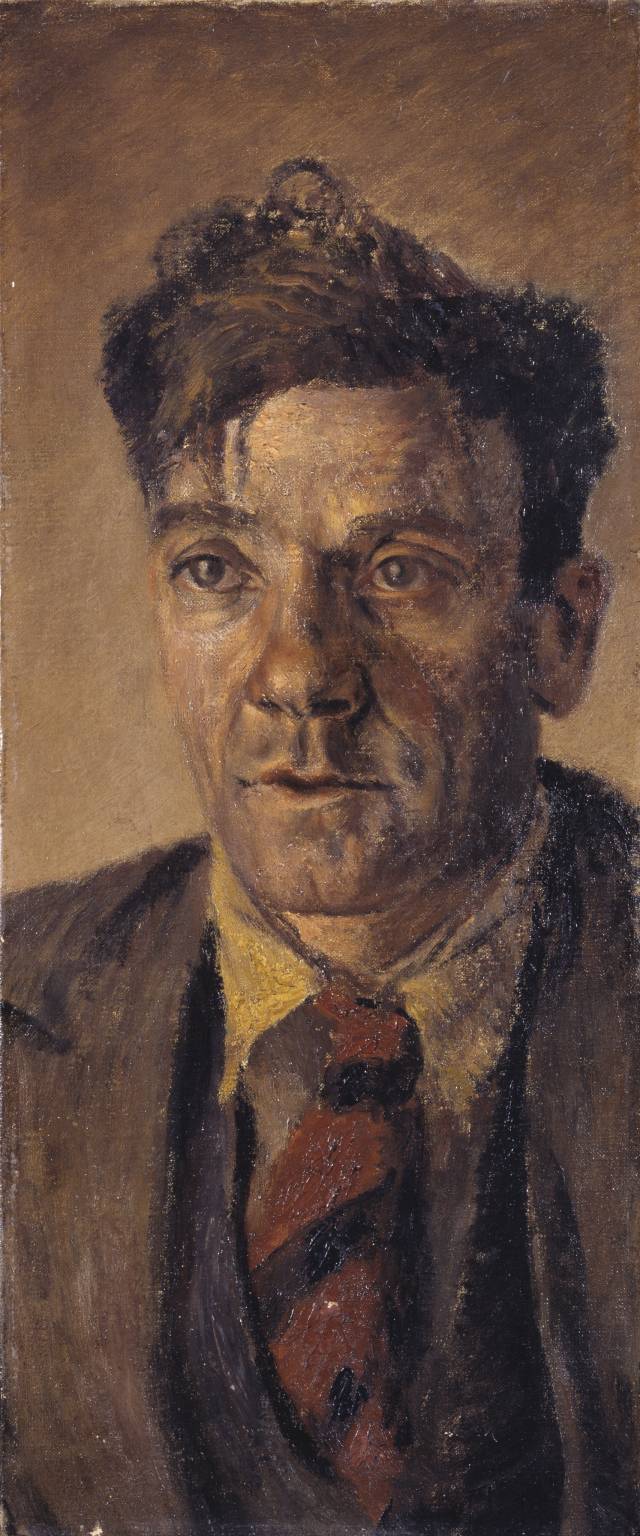

The Bolshevik Revolution and its fledgling worker-state offered hope and inspired many to discover Marxism. Clive Branson, Betty Rea and James Boswell were among several artists who joined the newly formed Communist Party of Great Britain. Rea and others travelled to Russia to see for themselves, and Pearl Binder and Cliff Rowe were among those who stayed on as working artists. Unlike in Britain where the Depression dried up sales and commissions, work for artists in the Soviet Union was plentiful.

Cartoon by James Boswell in Left Review of September 1936

Meanwhile working-class artists such as James Fitton and Percy Horton were already politicised by the British socialist and labour movements.

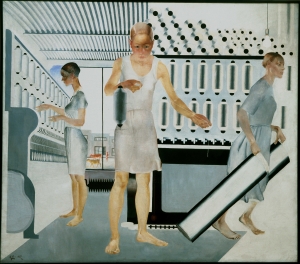

For socially committed artists the question was: how best to put their work at the service of political change? One way was to organise and in 1933 a handful of artists founded the Artists International (AI). Rowe initiated it on returning from the USSR, having being impressed by the professionalism and internationalism of Soviet artists’ organisations and the country’s egalitarian cultural policies and social integration of artists. The AI was also influenced by socialist and communist artists’ groups in Mexico, France and the US.

In 1934 as membership grew to 32, the AI defined itself as: ‘…The International Unity of Artists Against Imperialist War on the Soviet Union, Fascism and Colonial Oppression…’ It outlined its intention to spread Marxist beliefs through exhibitions, the press, lectures and meetings and by collaborating on posters, illustrations, banners and stage designs and maintaining international contacts with similar groups.

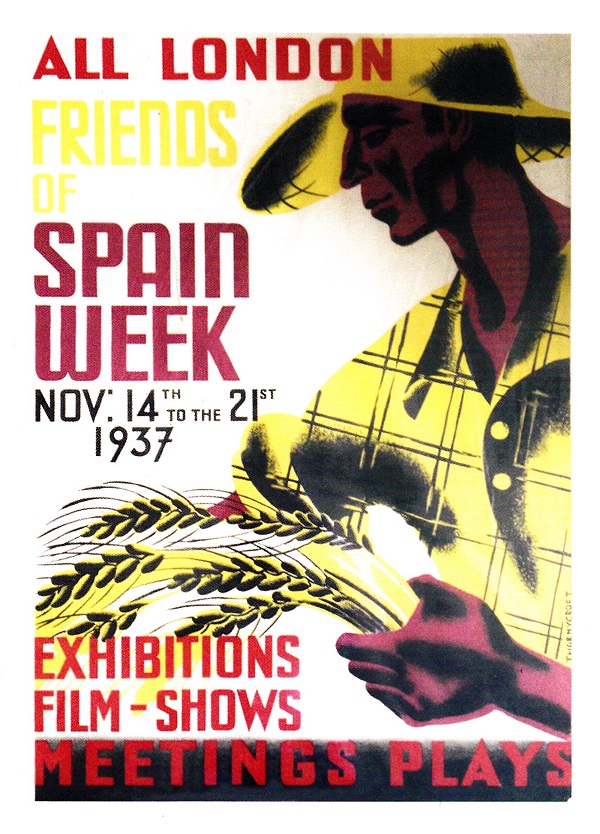

Poster by Priscilla Thornycroft

Just as the AI opposed establishment politics, so it challenged the dominant Art for Art’s sake aesthetic. Preached by Roger Fry and Clive Bell, this held that art should address purely formal problems and not be tainted by politics; whereas politically committed artists depicted the realities of working-class life and opposed individualism with collectivism. Influenced by William Morris’s socialist aesthetic, they challenged the hierarchy which placed ‘pure’ Fine Art above the Applied Arts. Indeed some artists rejected easel painting for being unique, exchangeable commodities, and turned to socially useful public arts such as banners and prints which democratised art. Boswell gave up painting in 1932, and he, Binder, Fitton and James Holland contributed biting condemnations of poverty and fascism in illustrations for Left Review (1934-38).

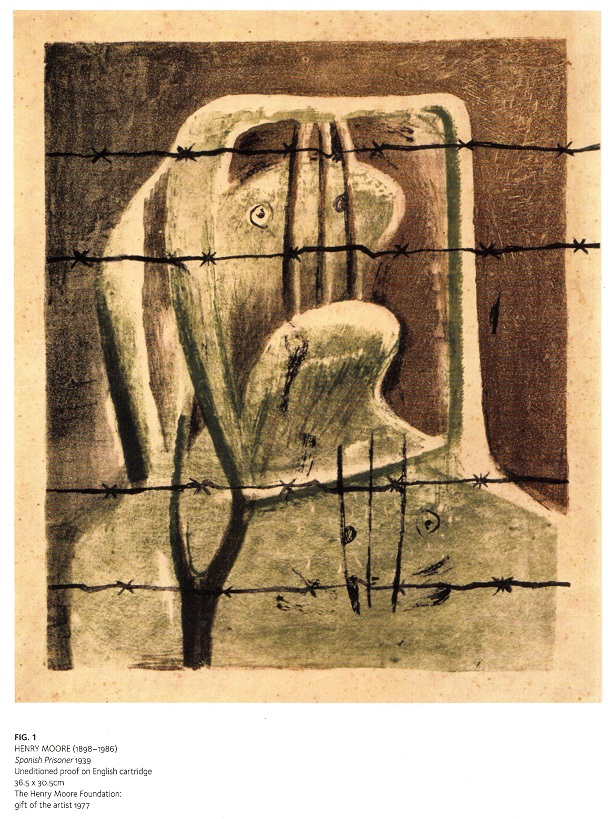

Henry Moore, Spanish Prisoner, 1939

In 1935 Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia and Hitler’s increasingly threatening belligerence caused the AI to temper its Marxist stance in the inclusive spirit of the Popular Front. Renamed the Artists International Association (AIA), it widened membership, including attracting established artists such as Laura Knight and Henry Moore, so gaining public gravitas and funds.

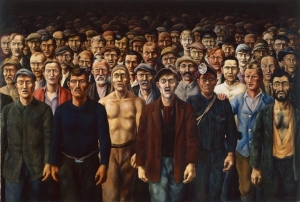

But it was the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War which truly united and galvanised artists into action. Appalled by the French and British governments’ unjust refusal to aid the Spanish Republic, numerous artists rallied to its defence in the belief that a second world war could only be averted by defeating Franco, Hitler and Mussolini in Spain. AIA membership surged to 700 in 1937 and had increased to 1,000 by the Second World War.

Felicia Browne, 1936, Tate Archive Letter, Portsmouth Evening News

For politicised artists the question was not whether to, but how to defend the Spanish Republic. Some, including Julian Bell and the communists Clive Branson and Felicia Browne, argued that in times of such political urgency direct political action superseded artistic commitment. They joined the British volunteers of the International Brigade, in which Browne became the only British woman combatant. She was killed in action, as was Bell.

The British Battalion's silk banner being held by Communist Party leader Harry Pollitt at Mas de las Matas, Aragón, Christmas 1937. The banner and carved pole were the collective work of Phyllis Ladyman, Jim Lucas and Betty Rea.

Other artists argued that they could be most useful by raising public consciousness and funds. The AIA arranged numerous events including exhibitions such as Artists Help Spain. Organised in 1936 by women in just two weeks, it raised the enormous sum of £500 for the Artists’ Ambulance and its medical supplies. Artists produced numerous leaflets, posters, floats, illustrations and fundraising events such public lectures, a cabaret and ‘Portraits to Help Spanish Medical Aid’. The British Battalion’s silk banner was made collectively, as Phyllis Ladyman embroidered Jim Lucas’s design and Rea carved a clenched fist for its carrying pole. Some works, such as Peter Perí’s emotive relief sculpture Aid Spain, conveyed anti-war content through traditional means.

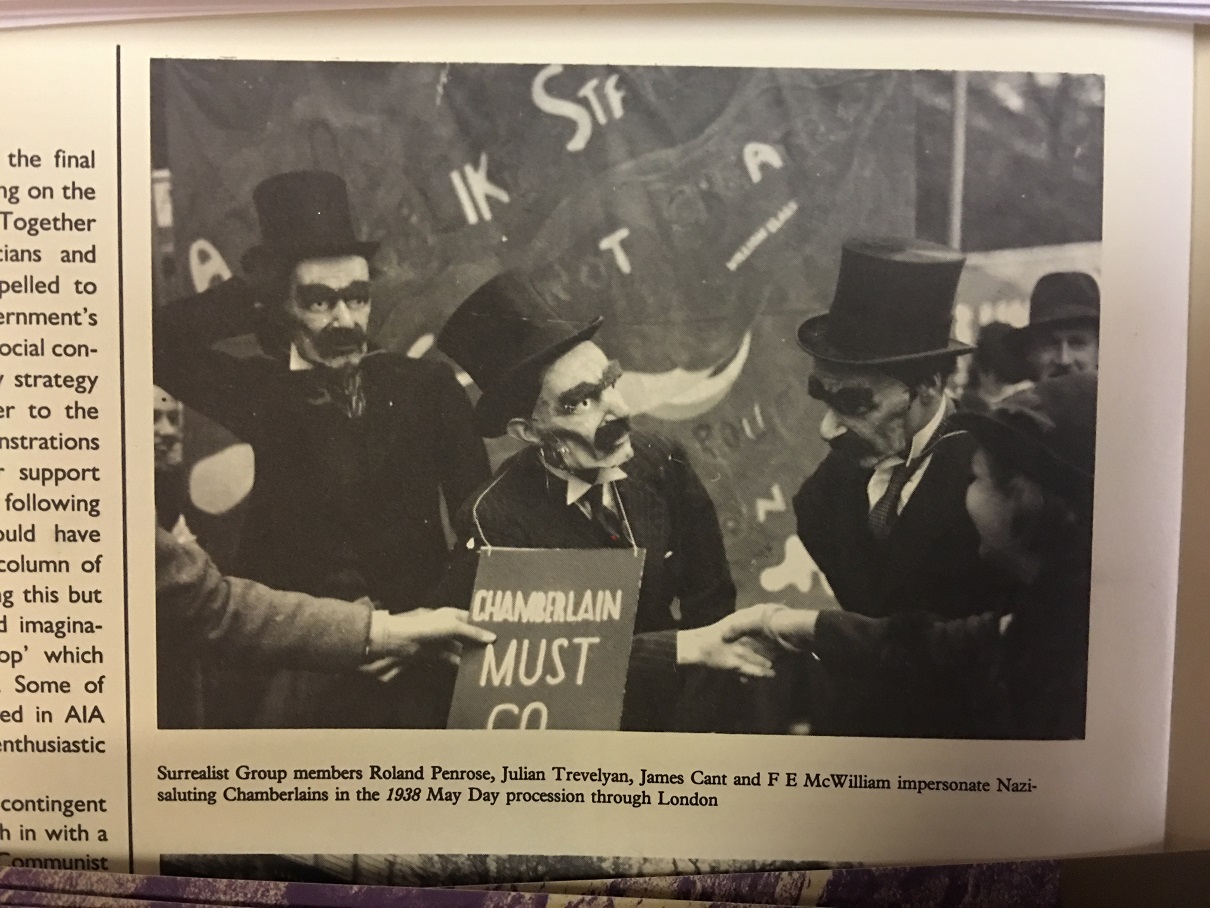

Surrealist artists impersonating Chamberlain, 1938. Image from ‘The Story of the AIA’ by Lynda Morris and Robert Radford (1983)

Two hundred artists marched as a contingent in the 1938 May Day parade, including the street action by four Surrealists, who dressed and masked as the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and danced minuets with his trademark furled umbrella. In 1939 Priscilla Thornycroft collaborated with Fran Youngman to paint ‘Spain Fights On, Send Food Now’, from tall ladders on a gigantic public hoarding, knowing that this action by two young women would publicise the cause by attracting the press. Even artists such as Henry Moore and Julian Trevelyan, whose works normally avoided overt political content, contributed posters or banners.

AIA artists were not alone in producing art for Spain. But the AIA was the largest and most organised group to do so. And its clear political focus acted as a forum for the exchange of ideas, particularly during collaborative projects such as banner-making and staging exhibitions.

While most artists still remained in their ivory towers, this minority took the radical view that artists could not escape the issues of their time. Rea explained: ‘The future of art hangs on the future of civilisation. It is time the artists began to think what sort of future they want and what they can do to get it.’

Christine Lindey's book ‘Art for All, British Socially Committed Art from the 1930s to the Cold War’ is published by Artery Publications and is available here. This article first appeared in ¡No Pasarán!, the magazine of the International Brigade Memorial Trust, see here.