Alain Badiou writes about the links between poetry and communism, with particular reference to the poetry of the Spanish Civil War.

In the last century, some truly great poets, in almost all languages on earth, have been communists. In an explicit or formal way, for example, the following poets were committed to communism: in Turkey, Nâzim Hikmet; in Chile, Pablo Neruda; in Spain, Rafael Alberti; in Italy, Eduardo Sanguinetti; in Greece, Yannis Ritsos; in China, Ai Qing; in Palestine, Mahmoud Darwish; in Peru, César Vallejo; and in Germany, the shining example is above all Bertolt Brecht. But we could cite a very large number of other names in other languages, throughout the world.

Can we understand this link between poetic commitment and communist commitment as a simple illusion? An error, or an errancy? An ignorance of the ferocity of states ruled by communist parties? I do not believe so. I wish to argue, on the contrary, that there exists an essential link between poetry and communism, if we understand ‘communism’ closely in its primary sense: the concern for what is common to all. A tense, paradoxical, violent love of life in common; the desire that what ought to be common and accessible to all should not be appropriated by the servants of Capital. The poetic desire that the things of life would be like the sky and the earth, like the water of the oceans and the brush fires on a summer night – that is to say, would belong by right to the whole world.

Poets are communist for a primary reason, which is absolutely essential: their domain is language, most often their native tongue. Now, language is what is given to all from birth as an absolutely common good. Poets are those who try to make a language say what it seems incapable of saying. Poets are those who seek to create in language new names to name that which, before the poem, has no name. And it is essential for poetry that these inventions, these creations, which are internal to language, have the same destiny as the mother tongue itself: for them to be given to all without exception. The poem is a gift of the poet to language. But this gift, like language itself, is destined to the common – that is, to this anonymous point where what matters is not one person in particular but all, in the singular.

Thus, the great poets of the twentieth century recognized in the grandiose revolutionary project of communism something that was familiar to them – namely that, as the poem gives its inventions to language and as language is given to all, the material world and the world of thought must be given integrally to all, becoming no longer the property of a few but the common good of humanity as a whole.

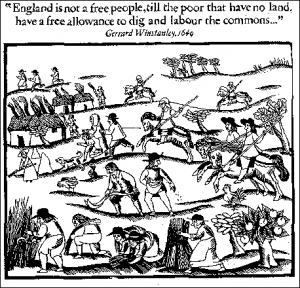

This is why the poets have seen in communism above all a new figure of the destiny of the people. And ‘people’, here, means first and foremost the poor people, the workers, the abandoned women, the landless peasants. Why? Because it is first and foremost to those who have nothing that everything must be given. It is to the mute, to the stutterer, to the stranger, that the poem must be offered, and not to the chatterbox, to the grammarian, or to the nationalist. It is to the proletarian – whom Marx defined as those who have nothing except their own body capable of work – that we must give the entire earth, as well as all the books, and all the music, and all the paintings, and all the sciences. What is more, it is to them, to the proletarians in all their forms, that the poem of communism must be offered.

What is striking is that this should lead all those poets to rediscover a very old poetic form: the epic. The communists’ poem is first the epic of the heroism of the proletarians. The Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet thus distinguishes lyric poems, dedicated to love, from epic poems, dedicated to the action of the popular masses. But even a poet as wise and as hermetic as César Vallejo does not hesitate to write a poem with the title, ‘Hymn to the Volunteers of the Republic’. Such a title evidently belongs to the order of the commemoration of war, to epic commitment.

These communist poets rediscover what in France Victor Hugo had already discovered: the duty of the poet is to look in language for the new resources of an epic that would no longer be that of the aristocracy of knights but the epic of the people in the process of creating another world. The fundamental link organized into song by the poet is the one that the new politics is capable of founding between, on the one hand, the misery and extreme hardship of life, the horror of oppression, everything that calls for our pity, and, on the other hand, the levying, the combat, the collective thought, the new world – and, thus, everything that calls for our admiration.

It is of this dialectic of compassion and admiration, of this violently poetic opposition between debasement and levying, of this reversal of resignation into heroism, that the communist poets seek the living metaphor, the nonrealist representation, the symbolic power. They search for the words to express the moment in which the eternal patience of the oppressed of all times changes into a collective force which is indivisibly that of raised bodies and shared thoughts.

The Spanish Civil War and Poetry

That is why one moment – a singular historic moment – has been sung by all the communist poets who wrote between the 1920s and 1940s: the moment of the civil war in Spain, which as you know ran from 1936 to 1939.

Let us observe that the Spanish civil war is certainly the historic event that has most intensely mobilized all the artists and intellectuals of the world. On one hand, the personal commitment of writers from all ideological tendencies on the side of the republicans, including therefore the communists, is remarkable: whether we are dealing with organized communists, social democrats, mere liberals, or even fervent Catholics, such as the French writer Georges Bernanos, the list is extraordinary if we gather all those who publicly spoke out, who went to Spain in the midst of the war, or even entered into combat on the side of the republican forces. On the other hand, the number of masterpieces produced on this occasion is no less astonishing. I have already noted as much for poetry. But let us also think of the splendid painting by Pablo Picasso that is titled Guernica; let us think of two of the greatest novels in their genre: Man’s Hope by André Malraux and For Whom the Bell Tolls by the American Ernest Hemingway. The frightening and bloody civil war in Spain has illuminated the art of the world for several years.

I see at least four reasons for this massive and international commitment of intellectuals on the occasion of the war in Spain.

First, in the 1930s the world found itself in a vast ideological and political crisis. Public opinion sensed more and more that this crisis could not have a peaceful ending, no legal or consensual solution. The horizon was a fearsome one of internal and external warfare. Among intellectuals, the tendency was to choose between two absolutely contrary orientations: the fascist and the communist orientations. During the war in Spain, this conflict took the form of civil war pure and simple. Spain had become the violent emblem of the central ideological conflict of the time. This is what we might call the symbolic and therefore universal value of this war.

Second, during the Spanish war, the occasion arose for artists and intellectuals all over the world not only to show their support for the popular camp, but also to participate directly in combat. Thus what had been an opinion changed into action; what had been a form of solidarity became a form of fraternity.

Third, the war in Spain took on a fierceness that hit people over the head. Misery and destruction were present everywhere. The systematic massacre of prisoners, the indiscriminate bombing of villages, the relentlessness of both camps: all this gave people an idea of what could be and what in fact was to be the worldwide conflict to which the war in Spain was the prologue.

Fourth, the Spanish war was the strongest moment, perhaps unique in the history of the world, of the realization of the great Marxist project: that of a truly internationalist revolutionary politics. We should remember what the intervention of the International Brigades meant: they showed that the vast international mobilization of minds was also, and before anything, an international mobilization of peoples. I am thinking of the example of France: thousands of workers, often communists, had come as volunteers to do battle in Spain. But there were also Americans, Germans, Italians, Russians, people from all countries. This exemplary international dedication, this vital internationalist subjectivity, is perhaps the most striking accomplishment of what Marx had thought, which can be summarized in two phrases: negatively, the proletarians have no fatherland, their political homeland is the whole world of living men and women; positively, international organization is what allows for the confrontation and in the end the real victory over the enemy of all, the capitalist camp, including in its extreme form, which is fascism.

Thus, the communist poets had found major subjective reasons in the Spanish war for renewing epic poetry in the direction of a popular epic – one that was both that of the suffering of peoples and that of their internationalist heroism, organized and combative.

Already the titles of the poems or collections of poems are significant. They indicate almost always a kind of sensible reaction of the poet, a kind of shared suffering with the horrible fate and hardship reserved for the Spanish people. Thus, Pablo Neruda’s collection bears the title Spain in Our Hearts. This goes to show that the first commitment of the poet is an affective, subjective, immediate solidarity with the Spanish people at war. Similarly, the very beautiful title of César Vallejo’s collection is Spain, Take This Cup from Me. This title indicates that, for the poet, the sense of shared suffering becomes its own poetic ordeal, which is almost impossible to bear.

However, both poets will develop this first personal and affective impulse almost in the opposite direction – that of a creative use of suffering itself, that of an unknown liberty. This unknown liberty is precisely that of the reversal of misery into heroism, the reversal of a particular anxiety-ridden situation into a universal promise of emancipation. Here is how César Vallejo puts it, with his mysterious metaphors, in Hymn to the Volunteers of the Republic:

Proletarian who dies of the universe, in what frantic harmony

your grandeur will end, your extreme poverty, your impelling whirlpool,

your methodical violence, your theoretical & practical chaos, your Dantesque

wish, so very Spanish, to love, even treacherously, your enemy!

Liberator wrapped in shackles,

without whose labour extension would still be without handles ,

the nails would wander headless,

the day, ancient, slow, reddish,

our beloved helmets, unburied!

peasant fallen with your green foliage for man,

with the social inflection of your little finger,

with your ox that stays, with your physics,

also with your word tied to a stick

& your rented sky

& with the clay inserted in your tiredness

& with that in your fingernail, walking!

Agricultural

builders, civilian & military,

of the active, ant-swarming eternity: it was written

that you will create the light, half-closing

your eyes in death;

that, at the cruel fall of your mouths,

abundance will come on seven platters, everything

in the world will be of sudden gold

& the gold,

fabulous beggars for your own secretion of blood,

& the gold itself will then be made of gold!

You see how death itself – the death in combat of the volunteers of the Spanish people – becomes a construction; better yet, a kind of nonreligious eternity, an earthly eternity. The communist poet can say this: ‘Agricultural builders, civilian & military, of the active, ant-swarming eternity’. This eternity is that of the real truth, the real life, wrested away from the cruel powers that be. It changes everything into the gold of true life. Even the accursed gold of the rich and the oppressors will simply become once more what it is: ‘the gold itself will then be made of gold’.

We might say that, in the ordeal of the Spanish war, communist poetry sings of the world that has returned to what it really is – the world-truth, which can be born forever, when hardship and death change into paradoxical heroism. This is what César Vallejo will say later on by invoking the ‘victim in a column of victors’, and when he exclaims that ‘in Spain, in Madrid, the command is to kill, volunteers who fight for life!’

Pablo Neruda, as I have mentioned, likewise starts out from pain, misery and compassion. Thus, in the great epic poem titled ‘Arrival in Madrid of the International Brigade’, he begins by saying that ‘Spanish death, more acrid and sharper than other deaths, filled fields up to then honoured by wheat.’ But the poet is most sensitive to the internationalism of the arrival in Spain from all over the world of those whom he directly calls ‘comrades’. Let us listen to the poem of this arrival:

Comrades,

then

I saw you,

and my eyes are even now filled with pride

because through the misty morning I saw you reach

the pure brow of Castile

silent and firm

like bells before dawn,

filled with solemnity and blue-eyed, come from far,

far away,

come from your corners, from your lost fatherlands,

from your dreams,

covered with burning gentleness and guns

to defend the Spanish city in which besieged liberty

could fall and die bitten by the beasts.

Brothers,

from now on

let your pureness and your strength, your solemn story

be known by children and by men, by women and by old men,

let it reach all men without hope, let it go down to the mines

corroded by sulphuric air

let it mount the inhuman stairways of the slave,

let all the stars, let all the flowers of Castile

and of the world

write your name and your bitter struggle

and your victory strong and earthen as a red oak.

Because you have revived with your sacrifice

lost faith, absent heart, trust in the earth,

and through your abundance, through your nobility, through

your dead,

as if through a valley of harsh bloody rocks,

flows an immense river with doves of steel and of hope.

What we see this time is first the evidence of fraternity. The word ‘comrades’ is followed later on by the word ‘brothers’. This fraternity puts forward not so much the changing of the real world as the changing of subjectivity. Certainly, at first, all these international communist militants have come ‘from far’, ‘from your corners’, ‘from your lost fatherlands’. But above all they have come from their ‘dreams covered with burning gentleness and guns’. You will note the typical proximity of gentleness and violence. This will be repeated with the image of a ‘dove of steel’: combat is the building not of naked violence, not of power, but of a subjectivity capable of confronting the long run because it has confidence in itself.

The workers and intellectuals of the international brigades, mixed together, have given new birth to ‘lost faith, absent heart, trust in the earth’. Because we are at war, the dove of peace must be a dove of steel, but it is also and above all, says the poem, a dove of hope. In the end, the epic of war that Neruda celebrates, what he calls ‘your victory strong and earthen as a red oak’, is above all the creation of a new confidence or trust. The point is to escape from nihilistic resignation. And this constructive value of communist confidence, I believe, is also needed today.

The French poet Paul Eluard picks up on two of the motifs that we have seen so far, and mixes them together. On one hand, as César Vallejo says, the international volunteers of the Spanish war represent a new humanity, simply because they are true human beings, and not the false humanity of the capitalist world, competitive and obsessed with money and commodities. On the other hand, as Pablo Neruda says, these volunteers transform the surrounding nihilism into a new confidence. A stanza of the poem ‘The Victory of Guernica’ says this with precision:

True men for whom despair

Feeds the devouring fire of hope

Let us open together the last bud of the future.

However, in the Spanish war Eluard is sensitive to another factor with universal value. For him, as for Rousseau, humanity is fundamentally good natured, with a good nature that is being destroyed by oppression through competition, forced labour, money. This fundamental goodness of the world resides in the people, in their obstinate life, in the courage to live that is theirs. The poem begins as follows:

Fair world of hovel

Of the mine and fields.

Eluard thinks that women and children especially incarnate this universal good nature, this subjective treasure that finally is what men are trying to defend in the war in Spain:

VIII

Women and children have the same riches

Of green leaves of spring and pure milk

And endurance

In their pure eyes.

IX

Women and children have the same riches

In their eyes

Men defend them as they can.

X

Women and children have the same red roses

In their eyes

They show each their blood.

XI

The fear and the courage to live and to die

Death so difficult and so easy.

The Spanish war, for Eluard, reveals what simple riches are at the disposal of human life. This is why extreme oppression and war are also the revelation of the fact that men must guard the riches of life. And to do so you must keep the trust, even when the enemy is crushing you, imposing on you the easiness of death. We clearly sense that this trust is communism itself. This is why the poem is titled ‘The Victory of Guernica’. The destruction of this town by German bombers, the 2,000 dead of this first savage experience that announces the world war: all this will also be a victory, if people continue to be confident that the riches of simple life are indestructible. This is why the poem concludes as follows:

Outcasts the death the ground the hideous sight

Of our enemies have the dull

Colour of our night

Despite them we shall overcome.

Poetic communism

This is what we can call poetic communism: to sing the certainty that humanity is right to create a world in which the treasure of simple life will be preserved peacefully, and that, because it has reason on its side, humanity will impose this reason, and its reason will overcome its enemies. This link between popular life, political reason and confidence in victory: that is what Eluard seeks to confer, in language, upon the suffering and heroism of the Spanish war.

Nâzim Hikmet, in the truly beautiful poem titled ‘It Is Snowing in the Night’, will in turn traverse all these themes of communist poetics, starting out from a subjective identification. He imagines a sentry from the popular camp at the gates of Madrid. This sentinel, this lonely man – just as the poet is always alone in the work of language – carries inside him, fragile and threatened, everything the poet desires, everything that according to him gives meaning to existence. Thus, a lonely man at the gates of Madrid is in charge of the dreams of all of humanity:

It is snowing in the night,

You are at the door of Madrid.

In front of you an army

Killing the most beautiful things we own,

Hope, yearning, freedom and children,

The City …

You see how all the Spanish themes of communist poetics return: the volunteer of the Spanish war is the guardian of universal revolutionary hope. He finds himself at night, in the snow, trying to prohibit the killing of hope.

Nâzim Hikmet’s singular achievement no doubt consists in finding the profound universality of nostalgic yearning in this war. Communist poetics cannot be reduced to a vigorous and solid certainty of victory. It is also what we might call the nostalgia of the future. The hymn to the sentry of Madrid is related to this truly peculiar sentiment: the nostalgia for a grandeur and a beauty that nevertheless have not yet been created. Communism here works in the future anterior: we experience a kind of poetic regret for what we imagine the world will have been when communism has come. Therein lies the force of the conclusion of Hikmet’s poem:

I know,

everything great and beautiful there is,

everything great and beautiful man has still to create

that is, everything my nostalgic soul hopes for

smiles in the eyes

of the sentry at the door of Madrid.

And tomorrow, like yesterday, like tonight

I can do nothing else but love him.

You can hear that strange mixture of the present, of the past and future that the poem crystallizes in the imagined character of the solitary sentry, confronted with the fascist army, in the night and snow of Madrid. There is already nostalgia for what true humanity, the combatant people of Madrid, is capable of creating in terms of beauty and grandeur. If the people are capable of creating this, then humanity will certainly create it. And, then, we can have the nostalgia for that which the world would be if this possible creation had already taken place. Thus, communist poetry is not only epic poetry of combat, historic poetry of the future, affirmative poetry of confidence. It is also lyric poetry of what communism, as the figure of humanity reconciled with its own grandeur, will have been after victory, which for the poet is already regret and melancholy as well as ‘nostalgic hope’ of his soul, past as well as future, nostalgia as well as hope.

With regard to the Spanish civil war properly speaking, Bertolt Brecht also committed himself by writing a didactic play, Señora Carrar’s Rifles, which is devoted to the interior debate over the need to participate in the right battle, whatever the excellent reasons may be to stay at a safe remove.

But perhaps the most important aspect is the following: as the independent communist that he has always been, Brecht is the contemporary of very serious and bloody defeats of the communist cause. He has been directly present and active in the moment of the defeat of German communism in the face of the Nazis. And of course he has also been the contemporary of the terrible defeat of Spanish communism in the face of Franco’s military fascism. But one of the tasks that Brecht has always assigned to himself as a poet is to give poetic support to confidence, to political confidence, even in the worst of all conditions, when the defeat is at its most terrifying. Here we rediscover the motif of confidence, as that which the poem must stir up based on the reversal of compassion into admiration, and of resignation into heroism.

To this subjective task Brecht devoted some of his most beautiful poems, in which the almost abstract focus of the topic aims to produce an enthusiasm of sorts. I am thinking of the end of the poem ‘InPraise of Dialectics’, in which we again find the temporal metamorphoses that I have already talked about – the future that becomes the past, the present that is reduced to the power of the future – all of which makes a poem out of the way in which political subjectivity supports a highly complex connection to historical becoming. Brecht, for his part, in Lob der Dialektik, poeticizes the refusal of powerlessness in the name of the future’s presence in the present itself:

Who dares say: never?

On who does it depend if oppression remains? On us.

On who does it depend if its thrall is broken? Also on us.

Whoever has been beaten down must rise up!

Whoever is lost must fight back!

Whoever has recognized his condition – how can anyone stop him?

Because the vanquished of today are tomorrow’s victors

And never will become: already today!

Must we, too, not desire that ‘never’ become ‘already today’? They pretend to chain us to the financial necessities of Capital. They pretend that we ought to obey today so that tomorrow may exist. They pretend that the communist Idea is dead forever, after the disaster of Stalinism. But must we not in turn ‘recognize [our] condition’? Why do we accept a world in which one percent of the global population possesses 47 per cent of the world’s wealth, and in which 10 per cent possesses 86 per cent of the world’s wealth? Must we accept that the world is organized by such terrible inequalities? Must we think that nothing will ever change this? Must we think that the world will forever be organized by private property and the ferocity of monetary competition?

Poetry always says what is essential. Communist poetry from the 1930s and 1940s recalls for us that the essential aspect of communism, or of the communist Idea, is not and never has been the ferocity of a state, the bureaucracy of a party, or the stupidity of blind obedience. These poems tell us that the communist Idea is the compassion for the simple life of the people afflicted by inequality and injustice – that it is the broad vision of a raising up, both in thought and in practice, which is opposed to resignation and changes it into a patient heroism. It tells us that this patient heroism is aimed at the collective construction of a new world, with the means of a new thinking about what politics might be. And it recalls for us, with the riches of its images and metaphors, with the rhythm and musicality of its words, that communism in its essence is the political projection of the riches of the life of all.

Brecht saw all this very clearly, too. He is opposed to the tragic and monumental vision of communism. Yes, there is an epic poetry of communism, but it is the patient epic, which is heroic for its very patience, of all those who gather and organize themselves to heal the world of its deadly diseases that are injustice and inequality; and to do so requires going to the root of things: limit private property, end the violent separation of the power of the state, overcome the division of labour. This, Brecht tells us, is not an apocalyptic vision. On the contrary, it is what is normal and sensible, reflecting the average desire of all. This is why the communist poem recalls for us that sickness and violence are on the side of the capitalist and imperialist world as we know it, and not on the side of the calm, normal and average grandeur of the communist Idea. This is what Brecht is going to tell us in a poem that carries the absolutely surprising title, ‘Communism is the Middle Term’:

To call for the overthrow of the existing order

May seem a terrible thing

But what exists is no order.

To seek refuge in violence

May seem evil.

But what is constantly at work is violence

And there is nothing special about it.

Communism is not the extreme outlier

That only in a small part can be realized,

and until it is not completely realized,

The situation is unbearable

Even for someone who is insensitive.

Communism is really the most minimal demand

What is nearest, reasonable, the middle term.

Whoever is opposed to it is not someone who thinks otherwise

It is someone who does not think or who thinks only about himself

It is an enemy of the human species who,

Terrible

Evil

Insensitive

And, in particular,

Wanting the most extreme, realized even in the tiniest part,

Plunges all humankind into destruction.

Thus, communist poetry presents us with a peculiar epic: the epic of the minimal demand, the epic of what is never extreme nor monstrous. Communist poetry, with its resource of gentleness combined with that of enthusiasm, tells us: rise up with the will to think and act so that the world may be offered to all as the world that belongs to all, just as the poem in language offers to all the common world that is always contained therein, even if in secret. There have been and continue to be all kinds of discussions about the communist hypothesis: in philosophy, sociology, economics, history, political science. But I have wanted to tell you that there exists a proof of communism by way of the poem.

Translated by Bruno Bosteels. This essay is from The Age of the Poets and Other Writings on Twentieth-Century Poetry and Prose, by Alain Badiou, edited and translated by Bruno Bosteels with an introduction by Emily Apter and Bruno Bosteels (London-New York: Verso, 2014). Thanks to Alain Badiou and Verso Books for permission to republish this essay.