Dylan Goes Electric

50 years after Dylan went electric, controversy still rages about Bob Dylan's politics. Steve Johnson reviews the debates.

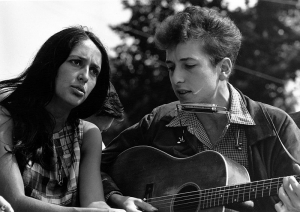

On 25th July 1965 Bob Dylan went on stage at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island. It was not his first time at the festival. In 1963 he was greeted as a voice of the young generation performing “Blowing in the Wind” in a glorious finale with fellow musicians which united Dylan’s contemporaries like Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary with an older generation of folk singers like Pete Seeger and Ronnie Gilbert from The Weavers. Followed by “We Shall Overcome” it seemed a perfect link between the new wave of folk singers and the burgeoning civil rights movement as well as paying homage to the earlier generation of folk musicians who had campaigned for peace and equality and against McCarthyism.

The response in 1965 however was different. Backed by multi- instrumentalist Al Kooper and the Paul Butterfields Blues Band Dylan went electric on a performance of “Maggie’s Farm”, and controversy still rages as to what happened next and what the significance was. It was not the first time Dylan had experimented with electric having brought out the album “Bringing it All Back Home” earlier in the year. Nor was he the only act at the festival to have played electric. Yet it is this set that is cited as a definitive moment when a break occurred between the old left folk tradition represented by Seeger, and the new younger followers of Dylan.

A number of myths have grown up around this particular narrative. The most enduring one is that Pete Seeger tried to cut through the cable wires with an axe. Anybody who has ever been to a music festival will know that an axe is not high on the list of items to pack but the narrative suits those who want to portray Seeger as representative of a dogmatic old left that wanted to dictate what form music should take.

There were however legitimate concerns from left musicians about commercialisation, and how capitalism could easily absorb protest music and thereby render it harmless. Opinions also still differ as to why some members of the audience jeered while others cheered. Singer Maria Muldaur has said it wasn’t so much Dylan going electric that caused some people to boo but the fact that the arrangements weren’t quite right. It didn’t actually sound very good!

Another myth that has grown up in the aftermath is that on Dylan’s British tour ten months later, members of the Communist Party tried to disrupt his performances culminating in the shout of “Judas” at Manchester Free Trade Hall. Various right-wing or liberal commentators have claimed that this was instigated by the Communist Party of Great Britain, led by its folk overlord Ewan MacColl. This conveniently ignores the fact that MacColl had long left the party by 1965 but bourgeois journalists rarely check their facts when they need to state a particular narrative.

Whilst there may have been some Communist Party members who were strong folk fans and who did perhaps take a purist line on what folk music should be, there were also Communist Party members who liked rock and roll, some who liked jazz and some who liked classical or a combination of genres. There was never a party line on what members should like nor was Dylan going electric ever the subject of a congress resolution. It may be some party members did heckle the electric Dylan because they thought he sounded crap, but the thought of Communists having emotions like other people and reacting accordingly is lost on commentators with a particular agenda.

It’s not however Dylan going electric in itself that should concern us, but how that moment was used by other people and how it coincided with Dylan’s own disengagement from political protest. Dylan had claimed inspiration from Woody Guthrie and some of his early songs like “Masters of War” and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carrol” were masterpieces of angry political commentary against the ruling establishment.

Like other young folk singers in the 1960s such as Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton and Judy Collins Dylan became identified as a protest singer, performing at Martin Luther King’s march on Washington in 1963. “Blowing in the Wind” having become a hit for Peter, Paul and Mary, Dylan became identified with both the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam war movement. It was quite clear however that by 1965 Dylan was becoming weary of being identified as a protest singer and did not appear at any more public protests. In an interview with folk magazine “Sing Out” in 1968 when asked about the Vietnam War he replied “how do you know, I’m not as you say for the war?” It seems unlikely he was for the war but he was making a clear statement that he was now only interested in playing music.

Although he was persuaded by his old friend Phil Ochs to appear at a Concert for Allende following the coup in Chile in 1973 his drunken performance and the fact some members of the audience were there just to see Dylan upset the organisers, especially Ochs, who had befriended murdered Chilean singer Victor Jara. Sadly Ochs was to take his own life not long after, having never achieved the fame Dylan had, due to his more overt political stand.

Dylan did venture back into political song writing in 1975 with his song “Hurricane” about the unjust imprisonment of black boxer Ruben “Hurricane” Carter. But not all his political concerns were progressive ones. In the 1970s he had developed contact with Rabbi Meir Kahane of the ultra-right-wing Jewish Defence League promising to finance the group’s activities although Kahane was to complain the money never materialised. This caused his fellow artist Mimi Farina (sister of Joan Baez) to write an open letter to him in the San Francisco Chronicle, seeking a reassurance that money from his concerts would not be helping to finance the Israeli military. Dylan still performs in Israel. But does he ever think of the Palestinians when he sings “How many years must a people exist before they’re allowed to be free?

Personally I quite like some of Dylan’s later electric output and don’t feel it necessary to take a political position on the authenticity or otherwise of anything other than acoustic. However the attitudes of some of those who welcomed that moment at Newport can be summed up by the critic Paul Nelson in “Sing Out” shortly afterwards.

Comparing Dylan and Seeger, he criticised the latter as someone who “subjugated his art through his continued insistence on a world that never was and never can be… I choose Dylan. I choose art.” In other words art is solely for art’s sake. Music should never be about the struggle for a better life and campaigning is a waste of time. It certainly suits the capitalist class to encourage young people to have that approach to the music they listen to. For that reason alone, this particular cataclysmic moment at Newport in 1965 should be viewed by the left as a retrograde step in both political and musical terms.

This article was first published in the Morning Star.