How to Protest: UK Politics, Press and Propaganda

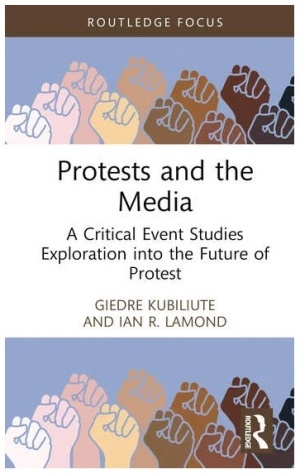

Brett Gregory interviews Giedre Kubiliute, principal author of Protests and the Media: A Critical Event Studies Exploration into the Future of Protest (Routledge, 2024)

BG: Hi, my name is Brett Gregory and I'm an associate editor with the UK arts, culture and politics website, Culture Matters. What follows is a wide-ranging interview with the principal author of ‘Protests and the Media: A Critical Event Studies Exploration into the Future of Protest’, an excellent book published in February 2024 which interrogates the interrelationship between protest, politics and propaganda in the UK.

Hi. What is your name, and what are the academic origins behind your publication?

GK: My name is Giedre Kubiliute. My path into research began through my Master's research project while studying at Leeds Beckett University, and that's where I met Dr Ian Lamond, the co-author of the book who was my research supervisor at the time. Ian's areas of research interests include conceptual foundations of event research, creativity and events of dissent, death, fandom, critical geography, whereas myself, having no previous academic background, my interest in protest and dissent is rooted in my own past growing up in Lithuania in the turbulent 1980s and 1990s, and the significance of dissent throughout my country's history.

BG: And what was the experiential key which helped you to unlock your motivation and determination with regards to completing this project?

GK: The book started as my Master's research project which I was due to start working on during the Covid-19 pandemic. All the events happening at the time, particularly the wave of the Black Lives Matter protests across the world, and Sarah Everard’s murder and the vigil. They were so emotionally charged and emotive, and the unprecedented context of the lockdown and the unknown that they were happening in, it added a whole new level of intensity. So, I personally found myself feeling really moved on some visceral level by all the protests taking place, and I wanted to interrogate that feeling further.

BG: You mentioned your Lithuanian background earlier. In what ways has this characterised your political outlook?

GK: It took me back to my childhood and the events of dissent I was a witness to from The Baltic Way of 1989 – which was a demonstration of close to 2 million people creating a human chain (see above) which connected Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia – to the hundreds of people defending the Lithuanian Parliament and the television tower in Vilnius, and standing up to the Russian tanks on the 13th January 1991 where 14 people lost their lives, to many other events I have seen or have been told about. So, to me protest events of defiance against oppression first and foremost, and they can bring hope, unite people and change the course of history, and they are tools to achieve societal change and innovation.

BG: And what wider sources have helped to define your own personal understanding of political dissent and protest?

GK: As Matthew Mars has said for innovation and the betterment of the existing situation to happen, there must be a form of so-called ‘creative disruption’. Or, as Henri Lefebvre said, a group of people who designate themselves as innovators must firstly intervene by imprinting a rhythm on an era, and their acts must inscribe themselves on reality.

So, seeing protest from my standpoint, it was very uncomfortable to observe how the media twisted and framed those events. Not only influencing how the public saw those specific events in question, but how the purpose and the driving force for that dissent was at times twisted to meet certain narratives that were perpetuated by certain media outlets or the state; and there was often a certain lack of will from the wider public to interrogate those narratives as well. And once you see it happen over and over again you can't unsee it: it happens everywhere all the time.

BG: Please tell us a little bit more about ‘Critical Event Studies’ as an academic subject, and how it can relate to our everyday lives.

GK: ‘Critical Event Studies’ interrogates the concept of an event. It frames the event as a rupture that can reveal the structures of power that underlie what's holding the daily life routines in place. Different theorists will use different terms which, while the meanings differ, they basically show that it is power or oppression that binds the routines of daily life into the practices of daily life. However, as well as exposing those power relationships, we also open up possibilities for different ways the relationships can be formed, and it's the event's ability to open up the multiplicity of alternative formations that enables resistance to existing power relationships.

When we stop seeing an event as something anchored to corporate or commercial constructions of events and project management, that enables us to draw on multiple fields and disciplines whilst seeking to explore their disruptive connections.

BG: Could you give a few specific examples?

GK: I mean there are so many of them, from a mainstream event studies perspective. We could look at the reactions to recent sporting mega events such as the Qatar World Cup or the recent iteration of the Olympic Games. We'll look at the debates of how to manage the most recent Eurovision song contest. Outside that narrow frame of reference, in the UK general elections, recent and emerging legislation around the forms protest can take; the huge upsurge in hate crime, particularly associated with sexual orientation and gender identity. None of them are critical events but they are ‘evental landscapes’ that warrant critical interrogation.

BG: Let's now look a little deeper into the mechanics and organics of political dissent and protest. What is the overall purpose, for example?

GK: Public dissent is really about publicly demonstrating counter-narratives. When we increase the level of knowledge and awareness of a topic the general trajectory of public discourse can be slightly nudged. It won't be an overnight solution, it's not a magic bullet kind of thinking. It's just a slight push but it can influence the change: it can draw people into coalitions as well, maybe those who were floating before. Of course, it can push people away too.

Extinction Rebellion protest

One of the people we interviewed for our book Pete, a scientist for Extinction Rebellion and other movements, made a very interesting and important point. There is often a misunderstanding that a movement behind a protest always seeks some sort of approval from the public which is then followed by an argument that more disruptive protest action will turn the public against the movement. And Pete argued that the purpose of a protest is never to make the wider public like the movement: it's to draw the public's attention to the problem, and that can often be lost in how the events are framed by the media.

BG: And what possible consequences can such actions and events have for wider society?

GK: Roland Bleiker, a Professor of International Relations, suggested that if we push the understanding of democracy beyond an institutionalised framework of processes and procedures, then dissenting protest could be viewed as a new kind of democratic participation that actually makes a meaningful contribution to the theory and practice of global democracy. But, instead, we witness governments refusing to deal with the causes that push people to protest and often those governments won't even attempt to eliminate those reasons but will instead put forward legislation to increase police powers and punishment in an attempt to squash the dissent which will only set the system up for further failure.

BG: So, how do governments, corporations and their media associates manage to keep the public at large in check?

GK: Public relations will often use propaganda and persuasion techniques that make use of emotional triggers instead of rational arguments, and often those are used without any regard for potential underlying ethical issues. Popular media sources and even some academics tend to frame protest by using traditional ‘angry mob’ or ‘mob mentality’ concepts which originate in historic crowd psychology. This cliché has been perpetuated to the extent where just one mention of a protest will evoke an image of an angry crowd in some people's minds.

BG: Can you give us a specific example of this?

GK: In April 2023 Extinction Rebellion organised an event called ‘The Big One’, and this event attracted approximately 100,000 participants and it was run in cooperation with the police. However, I'm pretty sure that hardly anyone has heard about it because we know that there are various reasons why the media will not cover peaceful gatherings.

If you speak to some journalists that have turned to activism I'm sure they'll tell you that disruptive events are partially driven and encouraged by the media itself, so the reporters are not exactly free to report the topics they feel are important as the power structures within their corporations decide what narratives and stories are acceptable. So, sometimes publishing a coverage of events may be the only way to touch on the issues at the heart of the dissent. However, for a journalist to be able to cover the event it has to be of significant scope and cause enough disruption to attract the media attention, so in that way media in itself can act as a catalyst for disruptive action.

BG: And the work of Noam Chomsky has been important in terms of your understanding of, for instance, ‘soft power’ shaping public opinion.

GK: In our book we talk a lot about how Herman and Chomsky’s ‘Propaganda Model’ is still very much alive today and it can be adapted for the new information technologies, and the way the information society operates. This model looks at how the so-called ‘raw information’ or ‘raw news’ gets filtered and manipulated by the factors of who owns the media firms, where their political interests lie, advertising as the primary income source; the reliance of the media on information provided by the government and so-called experts who are funded and approved by those sources and agents of power.

BG: What do you mean by the term ‘priority distortion’ with regards to mainstream mediated communication?

GK: Mainstream media, and particularly those sources specialising in ‘soft news’, they will use what we call ‘priority distortion’ by firstly reporting on some celebrity drama which will be followed by a story about political or social welfare issues, and that creates an absurd contrast in the reader’s mind and it devalues any interest in political engagement. When we spoke to a member of Extinction Rebellion they told us that the right-wing media will sometimes publish articles stating that the scientists are concerned about the climate emergency, but will not explain any details. So that makes such a topic and news too complex for some of the readers to understand or engage with; and, worryingly, as coverage of important social issues can be distorted and controlled by misinformation and omission, the public and some mid-level policy makers will still be basing their decisions on such filtered information.

BG: And ‘perspectivism’?

GK: ‘Perspectivism’ is a concept that looks at how we interpret the world around us based on our views and perceptions, and that is a result of the impact, the ideology and material conditions have on news reporting, which in itself is a process of choosing what information to report on and then using that information to carve it into further narratives. Most frequently we can witness the narratives that create a binary between us and them where ‘they’ will be positioned as problematic disruptive outsiders whose actions and nature are always so transparent to us, while they cannot fully appreciate the complexity of the virtuous ‘us’.

BG: Them and Us. Us and Them.

GK: So, there’s binaries are everywhere you can find them in the news reporting, ranging from the local reports about disruptive protesters in the UK, the asylum seekers in Europe, the narratives about gender identity, religion, to ultimately the West against Russia narrative which has been perpetuated by the Russian government over the last couple of years. We also witnessed it again when the right-wing media reacted to Extinction Rebellion's blockade of Murdoch's print works and used character assassinations of individual members of the movement in order to discredit the whole movement.

BG: Misinformation, disinformation, character assassinations … How do they keep getting away with it?

GK: Often the ruling elite will also use the concept of national security and intelligence to control any information leaks that could pose a danger to the ruling classes and corporations; and those who question the corporate political and military powers will be labelled as traitors. In the same way mainstream media can be used to drive the general public away from political debates by conditioning people to support the policies of political elites by claiming that those policies are essential for state security and public safety, although they are really aimed at silencing the voices that could be dangerous to those who are in power.

BG: And what else has your research uncovered?

GK: In our research it was interesting to observe how the media's portrayal of police actions at protests shifted depending on the event. All three events we spoke about in the book took place within about a year of each other during the lockdowns and under the same guidelines. However, the media was expecting the police to behave very differently in each of them; and not only that, the media can use a protest event as a basis to reinforce certain narratives that lie at the heart of the movement. In our book we explore how both right-leaning and left-leaning media displayed overall similar attitudes and coverage of the events around Sarah Everard’s vigil, but behind that coverage they had very different attitudes and discussions regarding the matter of women’s safety. And there are so many more examples of how public opinions are formed to avoid any interrogation.

BG: For example?

GK: One that really boils my blood is the conversations we are having about gender-neutral toilets. What we have now is an argument that women's safety is put in danger as essentially men posing at trans-women or otherwise can get access to women's spaces. So, the narrative has been turned to position two marginalised groups, women and trans-people, against each other and to put trans-people in a role of the threat when the real and, in my opinion, very obvious situation is that women are worried about their safety because men in disguise or not pose a threat to women's safety, and not only women's: any other marginalised groups really. It's a historical, cultural and societal problem that we are avoiding and we're not talking about.

So, what we do as a society now, we position two marginalised groups against each other as enemies and allow the real perpetrator to walk away unchallenged and unscathed. Those who pose the real danger just so happen to also hold the power in terms of capital, legislation, justice, policing, yet they don't get challenged. Why don't we as a society start having those uncomfortable conversations? Why aren't we challenging our male friends, family members? Why don't we educate our sons and employees and teach them the values they never had to be bothered to learn? Because it's an uncomfortable conversation, and people would rather find an enemy in a marginalised group that holds no power than challenge the real problem. Again, you see this everywhere and I think as a society, and particularly in this country, we will do everything in order to avoid any uncomfortable conversation. So, we will happily reinforce power structures even though they are contributing to the collapse of society, and put people and the planet in danger, just so, God forbid, we don't have to question anyone.

BG: Indeed. Utterly shameful. We are talking about at least 2,000 years of white patriarchy however – fully resourced by seemingly unlimited wealth and power – and which is, sadly, as embedded into our society and collective psyche as the foundations of Hadrian's Wall are embedded into the earth.

I believe it is going to take at least another 200 years of round-the-clock vigilance, education, activism and sacrifice for a truly permanent attitudinal change to be accepted on a national scale.However, isn't this one of the reasons why we choose to be here right now in 2024: to continue to help bring about progressive and positive change in others in some small but significant way? And with this in mind, I suppose we should continue and explore how propaganda and persuasion techniques are currently being employed online.

GK: The dominant social media platforms have concentrated ownership and form a very concentrated market. So, while on television and in the printed press the advertisers can target specific audiences, on social media multiple audiences can be targeted at once and this can be done artificially through bots which not only create automated posts, shares, likes and such but can be used as a tool to target and harass journalists and activists to flood them with hate and threads from artificially created accounts.

BG: And, of course, the reaction of the billionaire owners of these platforms is to simply hide away in their high-security ivory towers and count their money. As a consequence, where does that leave the rest of us?

GK: Facebook and Google algorithms are kept as a corporate secret so the owners control them and determine new sources for the general public. So the algorithms selected, exposure and audience fragmentation, they all create a hotbed for radicalisation, deep fake videos, voice cloning, generative text and other AI-generated content are becoming more and more convincing, and they have been widely used to spread disinformation during the US presidential elections, the Kremlin's attempts to discredit European governments, bots and fake accounts have been widely reported to be used by Russia to create counter-narratives around the war in Ukraine. It's also suspected that the Chinese government used fake news stories in a barrage jamming technique to overwhelm certain hashtags and make the readers see images of cotton fields as opposed to the tweet about the forced labour camps.

One of the people we interviewed for the book shared her horrific experiences, when following her public actions trolls created a fake ‘Only Fans’ account where they had her face superimposed and which was shared to her family, and those trolls used and altered photographs of her mother who had passed away to harass this person even further.

BG: It's like a war, an ideological, hyperreal war. Such a daily and nightly barrage of abuse must take its toll on activists and protesters on a personal level?

GK: We gathered from the people we interviewed for the book that a lot of people come to social activism not really knowing what to expect or rather not understanding how hard-hitting and life-changing this choice can be. First of all it's a huge and steep learning curve. An individual may think they might know enough and that they stand firmly on the ground, however joining a movement seems to open a floodgate of information or truth that one was not prepared for. Ultimately, it can create a sense of burden and loss and foster a sense of duty to create a change, and it will likely impact personal life choices going further as well which can have a negative impact on existing relationships, family ties, even professional life. Ultimately, it is likely to have a very significant impact on a person's mental health.

BG: Of course, naturally.

Green and Black Cross Group

GK: Then again there are other significant aspects. The question of finding one's identity and purpose within a movement; finally seeing that a change can be achieved and advocated for through collective action; network-building, finding like-minded people. So, there is a lot to consider, there is a lot of potential for life-changing happenings. Social movements also need to support activists more. Whether that support will be on a movement by movement basis, or it adopts the lines of something like the Green and Black Cross Group where an independent body of volunteer counsellors are established to support movements.

This is something both Ian and I want to interrogate further. The mediated manipulation of activism and activists has raised profound mental health and well-being issues for social movements, and to neglect working on those can cause high risk to individuals and to the work of the movements for social justice.

BG: Due to the absolute derelict state the UK is in at the moment I'm certain there are many, many conscientious readers and listeners out there who have seriously considered political activism of some sort but then again, on a personal level, is it worth the risk?

GK: There is always a risk but there are a couple of important things to bear in mind. Engaged democratic mobilisation for change that operates through a perspective of care and conviviality is much stronger on the left than it is on the right politically. It is opposed to the neoliberalist stance that promotes the destruction of the social through increased focus on the individual. We mentioned well-being and personal transformations that individuals undergo when they get involved in activism, and that's not to scare or put anyone off, it's to highlight how all-encompassing such transformations can be. And I think it's important for the movements to remember that they are creating lasting networks where peer support and education must be and it must remain one of the priorities and, hopefully, external players being aware of what activism entails. The various aspects and sometimes risks, they can also contribute to the societal change by offering their support and promoting and facilitating the culture of collaboration between different networks and groups.

The political right is far less about conviviality and much more about the spectacle and Donald Trump is an example of this above all others. Late capitalist democracy is very skilled at appropriating the tools of activism and converting them into commodified commercial opportunities, but activism isn't static either. What this means is that as activists we must always be adapting, growing and evolving. By assuming the approach we are now adopting that will affect change we will essentially be walking those techniques into the hands of those we are opposing, so only by being agile and creative we can keep ahead.

BG: Many thanks for your time, insights and patience, Giedre.