Why Christianity matters to socialism

James Crossley argues for the importance of the radical Christian tradition as an important resource for the revolutionary transformation of the world.

On becoming leader of the Labour Party in September 2015, Jeremy Corbyn envisaged living a society “where we don’t pass by on the other side of those people rejected by an unfair welfare system. Instead we reach out to end the scourge of homelessness and desperation that so many people face in our society.”

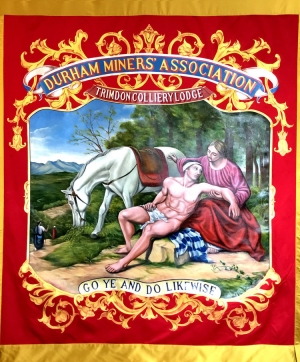

Every since that historic victory, Corbyn has repeatedly used the language of “not passing by on the other side.” It is an allusion to the Parable of the Good Samaritan from Luke’s Gospel and one popular among politicians. While David Cameron, Hilary Benn and others have used the parable to promote military intervention in North Africa and the Middle East (think the Good Samaritan violently beating the robbers), Corbyn, unusually for a contemporary politician, has used the parable to attack the scandal of increased homelessness, rough sleeping and the housing crisis.

These contradictory interpretations of a parable attributed to a figure like Jesus are not unusual: revolutionary and reactionary tendencies have always been part of Christianity, perhaps even present in the message of Jesus. The earliest traditions about Jesus have him predicting an imminent theocracy, not all of which would necessarily look progressive to us. It was likely to have been understood as a violent intervention in history, with new hierarchies established and subservient nations put in their place.

Christianity itself would later become integral to the Roman Empire. Some of this was due to changing religious affiliations in the Empire and Christianity adapting itself to Roman power. But it was not entirely alien to a theocratic message present from the beginning.

However, Jesus and his earliest followers’ hope for a new divine empire was tied in with stark attacks on the inequality and wealth, some of which were brought into sharper focus by the major building projects and land displacements in Galilee as Jesus was growing up. The first-century Jewish historian Josephus gives us some indication as to what this would have looked like in the case of one such building project, the town of Tiberias:

The new settlers were a promiscuous rabble, no small contingent being Galilean, with such as were drafted from territory subject to him [Herod Antipas] and brought forcibly to the new foundation. Some of these were magistrates. Herod accepted as participants even poor men who were brought in to join the others from any and all places of origin. It was in question whether some were even free beyond cavil. These latter he often and in large bodies liberated and benefited imposing the condition that they should not quit the city, by equipping houses at his own expense and adding new gifts of land. For he knew that this settlement was contrary to the law and tradition of the Jews because Tiberias was built on the site of tombs that had been obliterated, of which there were many there. And our law declares that such settlers are unclean for seven days. - Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.36-38

Jesus seems to have formed an alternative community to one where traditional households had been uprooted by aristocratic demand for greater surplus with a message revealing some awareness of the structural nature of poverty and wealth. The Acts of the Apostles suggests that these revolutionary impulses were kept alive in a community of shared goods that would later inspire Tony Benn in his defence of public ownership against the attacks from New Labour.

We should understand Jesus’ teachings in terms of Marx’s famous understanding of religion as “an expression of and protest against real wretchedness.” In a world where wealth was concentrated among a small aristocratic elite, Jesus was remembered as saying the rich would burn or be excluded from the coming kingdom while the poor would be blessed.

Parables like the Rich Man and Lazarus (where the rich man burns for being rich and the poor man Lazarus is rewarded because he was poor) and sayings such as “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” are in line with other expectations that the wealthy will eventually be overthrown and punished, at least if they did not give up their extreme wealth to those in need.

Pieter Cornelisz van Rijck, Kitchen Interior with the Parable of the Rich Man and the Poor Lazarus, 1610

This was to be, as the Acts of the Apostles note in a different context, turning the world upside down. But warning signs of this future were enacted in the present. People overcharging for sacrificial animals were the focus of Jesus’ ire as he was remembered for overturning the tables of the moneychangers and dove-sellers which would lead to his execution as a seditious threat.

The tension between reaction and revolution has continued throughout the history of Christianity. Clashes between elite power and the desire for radical democratic transformation or wealth redistribution simmered and occasionally boiled over in the history of English Christianity, leaving us with a long radical history, from the Peasants’ Revolt through the seventeenth-century radicals to the growth of the Labour movement and Keir Hardie’s desire to “stir up a divine discontent with wrong,” a saying referenced by Corbyn at the Labour Party conference in 2015. The language of this tradition was employed in the founding of the NHS and the successful Labour manifesto of 1945.

Thanks to countless dedicated socialists from the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp to revolutionaries travelling to Rojava, this was a tradition whose language would remain alive on the English left. The story of Jesus and the moneychangers was a prominent one in challenging “the one percent” at Occupy London Stock Exchange where St Paul’s Cathedral itself epitomised the tension: church leaders were uncomfortable with protesters while the grounds were simultaneously a readily available space for a sustained protest.

We now find ourselves in the position unusual for the Left: close to power. There have been encouraging discussions among Momentum and union activists about growing a working-class socialist culture “from below,” where social events, sports clubs, foodbanks, etc. become part of building a mass movement, see http://colouringinculture.org/cultural-democracy-home.

Historically, this socialism from below has had strong overlaps with Christian traditions. The impulses of Christianity which tackle poverty continue today, as in work of the Trussell Trust, whose role in foodbanks has made sure that Iain Duncan Smith does not forget Jesus’ words about poverty.

Yet, as I have discussed in a forthcoming book (Cults, Martyrs, and Good Samaritans: Religion in Contemporary English Political Discourse [Pluto, 2018]) there is evidence that much of the public does not like politicians explicitly invoking religion, Christianity and the Bible, particularly for grandiose claims about Christianity being the source of parliamentary democracy or free markets, as David Cameron claimed.

However, there does not appear to be widespread hatred of Christianity per se, not even beyond the pockets where church attendance remains relatively high. There is some indication that there is support for the Bible as a general moral code for helping others. This is something that should not be ignored by socialists. And Corbyn’s allusion to the Good Samaritan is precisely what is palatable for much of the British public: pithy, vague, but full of basic human decency.

But there is also evidence that Christianity can be associated with national identity. One recent study found that nearly a quarter of people viewed being Christian in ethnic terms, i.e. a signifier of being English or British despite the sharp decrease in church attendance in recent decades and the accompanying rise in those identifying with non-belief.

This can, of course, be dangerous for the left and fertile ground for the right. Theresa May and Nigel Farage have both tried to capitalise on this ethnonationalist understanding of Christianity. For example, when asked in Parliament about the respecting between Christmas of “mainstream Britain” and “minority traditions” of Diwali, Vaisakhi and Eid, May responded, “We want minority communities to be able to recognise and stand up for their traditions, but we also want to be able to stand up for our traditions generally, and that includes Christmas.”

May, like Farage, was attempting to appeal partly to a certain kind of working-class voter in the light of the EU Referendum. Uncomfortable though it may be, these issues should not be ignored by the English left where the struggle over national identity has been a difficult one. Here we can turn to the radical English tradition which has informed the contemporary left, including Corbyn and his mentor Tony Benn.

In fact, Labour have recognised this potential in the fight against UKIP and the Tories. Sam Tarry, co-director of Corbyn’s re-election campaign, talked about the importance of an English Labour movement promoting “the Peasants’ Revolt, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the Chartists, and the suffragettes and others” as a “socialist vision” which is also a “patriotic one, because nothing is more patriotic than building a society for the many; not the few.”

There is, of course, no doubt that religion can be a divisive issue on the left because of its well-known reactionary traditions. But Christianity (or any other religion) does not always have to be reactionary and socialist Christians won’t cease to be socialists because some of their co-travellers are not.

Left-wing Christianity has been central to English and British socialism and its legacy remains important to this day, whether in fighting poverty, keeping radicalism alive, providing ready-made community networks, or influencing the general language we use. None of this means, of course, that we all convert to Christianity or attend church on a Sunday morning. But if we want to transform this world, this radical tradition will prove to be an important resource.