Kimberley Reynolds describes how radical and transgressive circuses in twentieth-century children’s literature make the case for social and personal transformation. Above image: Family of Saltimbanques by Pablo Picasso, 1905

The circus has been a consistently popular setting, theme, metaphor and space in publishing for children from at least the nineteenth century, and writers, illustrators and readers are attracted to it for a variety of reasons. Foremost among these is the fact that the circus world is exotic, international, polyglot, excessive and carnivalesque. They combine animals from distant lands (in line with concerns about animal welfare, few circuses now have animal acts), astonishing illusions, gravity-defying aerialists and acrobats, the antic behaviour of adults in the roles of clowns, and sideshows featuring what were traditionally known as ‘freaks’. These features are all related to the identification of the circus by the first wave of modernist and avant-garde artists and authors as a quintessentially radical aesthetic space: a space where themes and ideas are explored with a view to challenging and changing how the everyday world is perceived and organised.

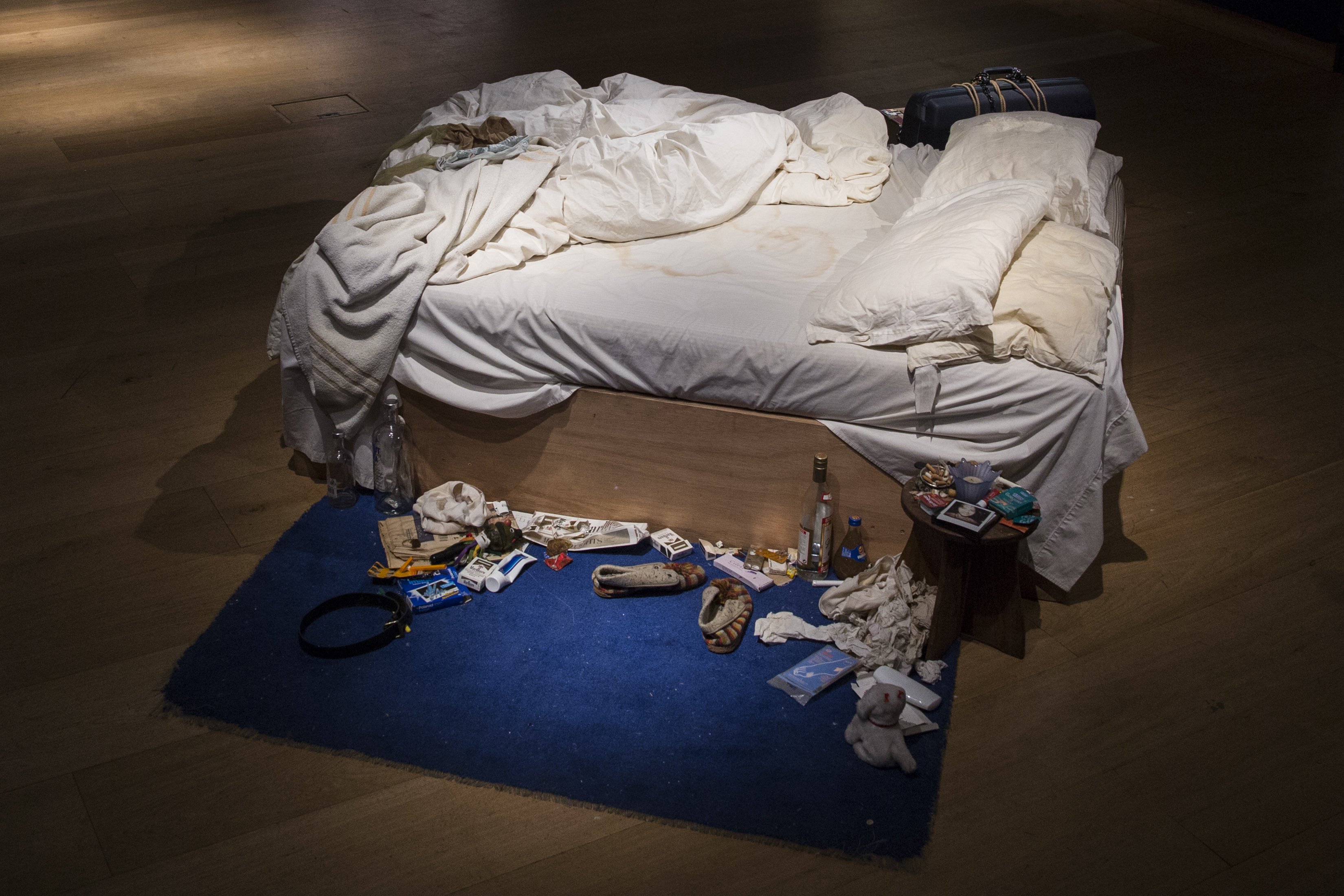

A sense of the radical appeal of the circus can be established with a few examples. For instance, during his Rose or ‘circus’ period, Pablo Picasso used images of circus performers as metaphors for the socially and economically precarious position of artists. Like circus performers, he suggests, innovative, challenging artists in early twentieth-century Europe and America were regarded as unimportant outliers by those in positions of power. Henri Matisse had a life-long interest in circuses and what they said about movement, freedom and creativity. This interest is documented in his book Jazz (1947), which was originally titled The Circus. More than half of the images it contains are of circus performances. Fernand Léger and Marc Chagall were fascinated by the way circuses liberated bodies and minds from convention. Their paintings often focus on the way circus acts create a sense of mental and physical liberation from the constraints of everyday life.

The Acrobat and His Partner by Fernand Léger

Circuses also offered artists new perspectives (from above and below) and celebrated speed, flight and simultaneity, as when multiple acts are taking place on the ground and in the air at the same moment. Circus rings and the contorted body shapes made by acrobats and aerialists lent themselves well to abstraction, while the transitions from acts featuring spangled, gravity-defying artists to lumbering elephants, ferocious big cats, bizarre clowns and the exceptional bodies found in circus sideshows gave a surreal, dreamlike quality to the circus experience. Perhaps most importantly, the inter-artistic nature of circus acts spoke to avant-garde interests in ‘Total Art’, meaning the combining of words, music, lighting, movement, and the plastic arts to provoke new sensations and perceptions.

Mikhail Bakhtin has shown how, by inducing new outlooks on the world, carnival, of which circus is one form, feeds cultural change. This understanding points to the subversive potential of circuses. In Ant-Nazi Modernism, Mia Spiro points to the way that the decades which witnessed the rise of fascism and Nazism saw the deliberate use of circuses to challenge the world view they promulgated. This deployment works well since circus life and circus acts stood for everything such regimes sought to suppress. They were ethnically, socially, and sexually diverse; they mixed levels of discourse; they displayed fluidity, eroticism, exoticism, and hybridity. The peripatetic nature of circuses means they were also free from geographical and nationalistic boundaries. This was as true on the page as under the Big Top or on the canvas. For instance, in Djuna Barnes’s novel Nightwood (1936), the circus is the only place where lesbian, transgender and other characters who struggle to fit into life in 1930s Paris and America can be at ease. Barnes makes the circus a space where, ‘no one is “alien” because everyone realizes that social positions, race, [and] sexuality are performances’ (Spiro 73).

Understanding the performative nature of all aspects of social life – not least in political displays – undermines the kind of mass spectacles by which totalitarianism asserts its power. So, for instance, performance theories relating to audience response compare the different effects on spectators of circuses and the huge, highly choreographed rallies favoured by Nazi propagandists. These mass spectacles were a deliberately hypnotic, homogenising and coercive kind of event. Their effect was to make most participants and observers unquestioning and conformist. Circuses, by contrast, are energising and individualistic; performances are not designed to lull audiences, but to provoke them. Their astonishing and often dangerous acts make audiences ask, ‘how do they do that?’ In this way, spectators are encouraged to recognise that they are watching tricks and illusions and to think about and deconstruct them – exactly the opposite effect of the Nazi rallies.

Circuses offered abundant metaphoric potential for celebrating freedom of thought, movement and interaction at a time when all of these were under threat. This made them valuable subjects for those artists and writers who were opposed to the divisive, hierarchical, nationalistic, and militaristic politics of the far right. In their hands, the circus was simultaneously offered as a site of intellectual and cultural provocation and a place of delight that appealed not just to a cultural elite but to large and mixed audiences. Children have always been part of the circus audience, and in circus stories, children are present as both performers and spectators. This does not mean that circuses are good places for the young. The experiences of real child circus performers have often been brutally abusive, and many of the first circus stories for children concentrated on this aspect of circus life. Stories about the sufferings of young circus performers make up a complete subgenre, but here my focus is on the way the circus setting was used by children’s writers and illustrators to introduce to their readers some of the artistic experiments and political critiques found in arts and letters from the first half of the last century.

Transformation and transgression in juvenile circus stories

Soviet writer Yuri Olesha’s The Three Fat Men (1928) overtly uses the circus to criticise oppressive rule and to celebrate imagination, creativity and intellectual freedom. This is a story about revolution: in it the oppressed people in an unnamed town rise up against the ‘Three Fat Men’ who rule their land and literally consume all its resources. Though it is not geographically or chronologically anchored in a particular time or place, because its author was living in the new Soviet republic and the story was completed just one year after the series of revolutions that saw the old imperial Russian rule replaced by the world’s first communist society, it is difficult not to link the book to those events. The revolution is led by members of a circus. One of these is Tibbulus the Tightrope walker and the other Suok, the girl acrobat, but even before they begin to take control of the events, a circus act has been encouraging the people to disrespect their three fat leaders. For instance, the three are represented on a stage by a trio of fat, hairy apes while a clown sings:

Like three great sacks of wheat,

The Three Fat Men abed!

For all they do is eat

And watch their bellies spread!

Hey you Fat Men, beware:

Your final days are here! (17)

The clown is right. The surreal plot, which includes separated twins, kangaroo trials and arbitrary sentences, a living doll, a talking parrot with a beard and a great many extravagant banquets, culminates in the overthrow of the Three Fat Men. The people are inspired to liberate themselves by those with courage, creativity, education and morals. All of the provocateurs are connected to the circus.

The Three Fat Men is aimed at able readers, and Olesha’s use of the circus is deliberately political. But books for younger readers also celebrate the internationalism, category mixing, simultaneity and Total Art found in modernist painting and writing. One of these is Samuil Marshak and Vladimir Lebedev’s The Circus (1925). This belongs to the outpouring of much-admired books produced in the first decades of Soviet rule, often by avant-garde writers and artists who hoped that they were helping to build society anew. For its original readers the book’s internationalism mirrored the drive to unite the many countries and peoples, with their different languages, eye shapes, skin tones, hair colours and fashions, that made up the new Soviet Union. It also supports the work of transforming an illiterate peasant culture into one which was both literate and ready to welcome, rather than fear or resent, modern technology.

Cover of The Circus and Other Stories, by Lebedev

The Circus begins with a poster based not on the highly decorated traditional fairground graphics usually favoured by circuses but on modern advertisements, as seen it its use of clean lines, sharp typography and white spaces. Huge, repeated exclamation points convey that very modernist quality of energy, while the text promises eclecticism in the form of ‘A rider from Rio,/An aerial trio/…. Jacko, the famous clown… all the way from Paris.’ Inside, a black tightrope walker is used to familiarise the workings of a telephone message, showing modern technology as thrilling but unthreatening, while a green musician is introduced as the wife of a Soviet clown. In line with the modernist appreciation of speed and dynamism, many images show figures in motion, zooming this way, galloping that, balancing precariously and defying gravity.

In the British-produced The Circus Book (1935), by Wyndham Payne with illustrations by Eileen Mayo, Japanese acrobats practise on one page while a man in evening dress is shown working alongside clowns and performing horses ridden by a bear and a lion on another. All are very familiar circus images, but when considering the significance of representing the way categories were mingled under the Big Top in these books, it is important not to forget the extent to which in interwar Europe, racial and national origins, sexuality, and physical development could determine a person’s fate. From policies in Nazi Germany to fascist demonstrations in London, Jews, Romani (a group closely associated with circuses) and others deemed inferior by those in authority were vilified and often attacked. The Circus Book makes much of the internationalism and inclusiveness of circuses. It asks children to admire the ability of circus performers to speak many languages so they can work together: ‘… circuses engage artists of every nationality so you can imagine the babel of tongues behind the scenes. Some of the directors can give orders in half a dozen different languages, nearly all the artists can speak at least two or three besides their own, and a well-known clown was able to do his act in twelve languages’ (8). This short information book is not overtly provocative or revolutionary; nevertheless, readers of the book are invited to admire what elsewhere in society was being presented as suspect.

Undoubtedly the most famous circus story for children is Dumbo, as told through the 1941 Walt Disney animated feature film. The artwork in this circus story (which began life as a children’s book and generated many spin-off picturebooks) has a modernist edge that subtly comments on, for instance, the alienation of workers and the loss of identity in modernity as in the impressionistic depiction of the roustabouts who set up the Big Top in a storm, and crowds fleeing as the huge tent collapses when Dumbo knocks over the ‘Pyramid of Pachyderms’. Expressionistically-coloured scenery conveys mood, while Freudian-inflected experimental sequences such as ‘Pink Elephants on Parade’ bring in other avant-garde interests around subjectivity, interiority and the psyche. The most pointed aspect of its radicalism focuses on racist policies in the United States at the time. This occurs in the section where Dumbo and Timothy meet Jim Crow and his gang. The name ‘Jim Crow’ refers to the laws that enforced segregation the in the US up to the 1960s. The crows dress and have the mannerisms of scat/jazz musicians: jazz clubs were places where whites and blacks often mixed. Dumbo and Timothy also mix with the crows in defiance of the segregationist agenda, and it is the crows who enable Dumbo to fly and become a hero. Their knowledge of psychology leads to the ‘magic’ feather that persuades Dumbo he can fly.

The Circus of Adventure, by Enid Blyton

There is nothing obviously radical about Enid Blyton’s The Circus of Adventure (1952); nevertheless, when the four adventurers, Philip, Dinah, Lucy-Ann and Jack, and the young central European prince who is in their charge seek refuge in a circus as they flee from a palace coup, behaviours that would have been suspect in other settings are valued. For instance, the young prince, Gustavus Aloysius, known as Gussy, gives a bravura performance as a girl, when soldiers ransack the circus, looking for the fugitives. The four British children have also been disguised with grease paint, circus costumes and an invented language. Because this is a circus and so outside what the soldiers consider to be the real world, they see insignificant itinerant performers rather than their prince and his middle-class British minders, and soon depart. The success of the children’s performances owes everything to the help of their circus friends. Their class background, age and nationality become unimportant, and the children are valued for their skills with animals and their willingness to join in the work of keeping the circus on the road.

As in the mythology that has grown up around circuses, all the members of the circus are portrayed as a big family, though they come from many countries and speak dozens of languages (‘Ma’ is Spanish, her husband is English, and their son seems to speak every language there is). Outside hierarchies are also of little consequence to the members of the circus. When the young prince objects to his treatment by, ‘Ma’, the woman who plays his grandmother, she responds, “Pah! ...You’re just a boy. I’ve no time for princes.” The narrator reinforces her statement by observing approvingly, ‘And she hadn’t’ (148). Such a celebration of classless internationalism is highly unusual for the broadly conservative Blyton.

The transformative effects of the circus on Gussy prove permanent. His time with the performers (and, of course, the four British children) has made him a stronger, better young man with a new, more respectful, attitude to his people and those who lack his social position. Gussy, it is implied, is on his way to becoming a modern ruler and a better ally for Britain. This is arguably a convenient than a radical conclusion from a British perspective, yet for much of the book even an author known for finding foreigners suspicious turns a circus full of ‘others’ into loyal, creative, heroic friends who use their circus skills to thwart a coup. The circus setting, then, shapes the book’s message and refashions the author’s ideological assumptions.

This brief sample gives a sense of how circus stories produced during the first half of the last century shared interests, agendas and modes with the experimental arts and letters produced by some of the best known modernist artists and writers. My growing collection of circus stories shows that for many writers and illustrators, the circus continues to provide an aesthetically and politically radical space, theme and metaphor that helps them make the case for social and personal transformation.