Women's rights and class relations: George Bernard Shaw's 'Pygmalion'

George Bernard Shaw (26th July 1856 to 2nd November 1950) was the second Irish winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, awarded to him two years after William Butler Yeats, in 1925. At the award ceremony his work was described as “marked by both idealism and humanity, its stimulating satire often being infused with a singular poetic beauty”.

Shaw was about as enthusiastic about the award as Beckett was over forty years later. “I can forgive Alfred Nobel for having invented dynamite, but only a fiend in human form could have invented the Nobel Prize”. He did not attend the award ceremony or other celebrations, nor did he accept the money.

When Shaw received the award, he was almost seventy years old. It was his play about Joan of Arc, Saint Joan (1923), written in the year of her canonisation, that had swayed the Nobel committee, as they managed to look past Shaw as the author of Pygmalion, Man and the Superman and Major Barbara.

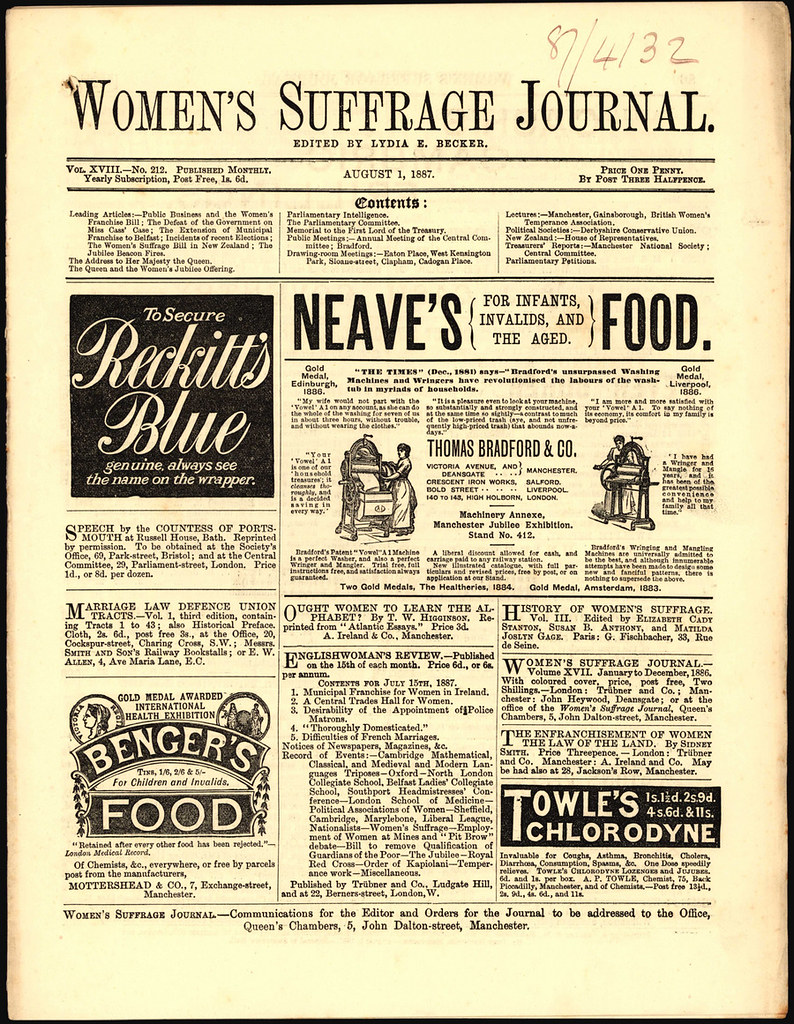

Shaw had declared at the founding of the Shelley Society on 10 March 1886, “I am, like Shelley, a Socialist, an Atheist, and a Vegetarian”. In 1882 he read Das Kapital in French translation, as no English version was yet available, and this was a turning point in his life. In 1884 he joined the socialist-oriented Fabians, a political society founded by intellectuals, which had its heyday in the period from 1887 to 1918. Shaw soon played a leading role here, writing some radical liberal pamphlets for them with demands for land reform, abolition of indirect taxes and women’s suffrage.

Pygmalion

Shaw’s perhaps most famous comedy is Pygmalion (1912). The immediate social background is the swelling British women’s suffrage movement, which was increasing in strength at this time, culminating, among other things, in the proclamation of International Women’s Day. The main themes of the play are women and class.

Pymalion was a mythological Greek artist who had become a misogynist. However, when he created a female figure from ivory in accordance with his own fantasy, he fell in love with her and implored Aphrodite to bring her to life. Then he married her. In the play, Professor Henry Higgins, international luminary in the field of phonetics, meets the flower-seller Liza Doolittle and boasts to his colleague Pickering that he can pass the working-class woman off as a duchess within a short time. They wager money on it. So like Pygmalion the misogynist, Higgins plans to create a character demonstrating his skill.

Shaw’s Pygmalion is about practical, intelligent women from different social classes. In addition to Liza Dolittle, two other women are significant: Mrs. Pearce, Henry Higgins’ Scottish housekeeper, and his mother, Mrs Higgins. Mrs Pearce, whose name could equally be of Irish origin, asks practical questions after Liza arrives and protects Liza: “Will you please keep to the point, Mr. Higgins. I want to know on what terms the girl is to be here. Is she to have any wages? And what is to become of her when you’ve finished your teaching? You must look ahead a little.”

Quite unimpressed by her employer, this woman speaks in very practical terms about economic and social aspects concerning the young woman’s position in the household, as well as her income, and she realistically foresees difficulties after the wager is won or lost. Undaunted, Mrs Pearce also watches over Liza’s dignity. She corrects Higgins’ behaviour and his crude expression (the man who plans to teach Liza ‘refined’ manners and speech), demanding some control over these in Liza’s presence. In this respect, Mrs. Pearce, who comes from the same class as Liza, assumes the role of her defender almost from the beginning.

As the audience hears from Liza later, she completely sees through Higgins’ class prejudice and his related contempt for humanity: “Mrs. Pearce warned me. Time and again she has wanted to leave you (…). And you don’t care a bit for her. And you don’t care a bit for me”. Liza has also brought about a change in Mrs Pearce, as Henry Higgins tells his mother: “before Eliza came, she used to have to find things and remind me of my appointments. But she’s got some silly bee in her bonnet about Eliza. She keeps saying ‘You don’t think, sir’: doesn’t she, Pick?” and Pickering confirms, “Yes: that‘s the formula. ‘You don’t think, sir.’ Thats the end of every conversation about Eliza.”

Interestingly, Mrs Higgins expresses a similar insight. Like Mrs Pearce, she raises “the problem of what is to be done with her afterwards.”. So too within the bourgeoisie there is a practical woman who sees the situation and the dangers clearly, with readers being alerted to her unconventional past in a stage direction. Like Mrs. Pearce, she recognises that switching Liza to the bourgeoisie’s way of life would result in her no longer being able to support herself: “The manners and habits that disqualify a fine lady from earning her own living without giving her a fine lady’s income! Is that what you mean?”. Ultimately, however, despite everything, there is a clear class difference between the two older women. Mrs Higgins clearly articulates a reservation about the young working-class woman when she says at the end, in the face of Liza's rebellion against her son, “I’m afraid you’ve spoiled that girl, Henry”.

Liza herself confidently insists on her human equality from the beginning: “I’m a respectable girl”and “I got my feelings same as anyone else”. At the start she insists on her right not to be watched by any police and wants to pay for Higgins’ language lessons because he holds out the prospect of better employment in a florist’s shop if she can ‘improve’ – that is, change – her pronunciation to copy that of the bourgeoisie.

She also prefers Pickering to the cynical Higgins because he calls her ‘Miss Doolittle’ and treats her kindly and courteously. She is clear that Higgins does not do this. Despite Higgins’ sarcasm and his indifference towards her further career, Liza asserts her dignity and ultimately emerges as the strongest person in the play. Especially after Higgins has actually been able to pass her off as a duchess in society, the latter now smugly celebrating his victory with Pickering and conceding no part in it to Liza, she rebels.

There is no bourgeois male figure of comparable stature. The gentlemen are not aware of this, of course. Shaw does not make it easy for his mainly middle-class audience to grasp his intention either. We are presented with highly educated men, erudite linguists, as well as a representative of the working class, Liza’s father Alfred Doolittle, who is in no way inferior to the academics in intellect.

Higgins is deeply contemptuous of Liza, whom he thinks, as he repeatedly points out, he has taken “out of the gutter”, to which she can return when he has won his bet: “when I’ve done with her, we can throw her back into the gutter”. He calls her a “baggage” and “dirty”. Higgins is misanthropic and views women as mindless beings who expect from life chocolate, clothes, taxis as well as a ‘good’ marriage, as he expresses several times: “Think of chocolates, and taxis, and gold, and diamonds. (…) And you shall marry an officer in the Guards, with a beautiful moustache” . A woman’s self-realisation through her own work does not occur to him. In this context, it is all the more understandable that his greatest crisis arises when Liza tells him that from now on she will make her living by teaching. That this will involve phonetics is his greatest threat, for Liza has a more musical ear than he and can go far.

Pickering has a somewhat gentler nature than Higgins. He treats Liza with more respect. But despite better manners, like Higgins he thinks the wager is won when Liza performs the great miracle and is able to pass herself off as a duchess. Together with Higgins, he enjoys the moment of this triumph without admitting that it is actually Liza’s achievement. Nor does he ever ask the question that was uppermost in the minds of the women – what is to become of Liza now?

Women's rights and class relations

The play is as much about class relations as it is about women’s rights. For Shaw, the two are inseparable. Liza Doolittle has a strong sense of her own worth from the very beginning. Several times she she insists on her equality with others. In the first scene she insists on her rights: “He's no right to take away my character. My character is the same to me as any lady’s”, and “I’ve a right to be here if I like, same as you.” She doesn’t expect any alms either, but wants to sell flowers or pay for her lessons: “Well, here I am ready to pay him — not asking any favour — and he treats me as if I was dirt.”

Liza’s father Alfred Doolittle comes across to a bourgeois audience as uneducated and unsophisticated, almost comical, yet he has enormous self-confidence and belongs unmistakably to the working class. Like Liza, he demonstrates class consciousness and the potential of this class:

“I’m one of the undeserving poor: thats what I am. Think of what that means to a man. It means that hes up agen middle class morality all the time. (…) I don’t need less than a deserving man: I need more. I don’t eat less hearty than him; and I drink a lot more. I want a bit of amusement, cause I’m a thinking man. I want cheerfulness and a song and a band when I feel low. Well, they charge me just the same for everything as they charge the deserving. What is middle class morality? Just an excuse for never giving me anything. (…) I’m undeserving; and I mean to go on being undeserving.”

This tremendous statement of humanity, is reminiscent of Shylock's speech in The Merchant of Venice, when he holds up a mirror to the complacent Christians, denouncing their hypocrisy and forcefully and simply demonstrating his equal humanity:

“I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us do we not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die?” (Act 3, Scene 1)

Again and again Doolittle emphasises that he does not want to be ‘improved’. That is why he does not take the 10 pounds offered to him, but only five. He wants to enjoy himself for one night.

Shaw’s insistence on the human superiority of the working class is also reflected on a linguistic level. For months, Higgins drills Liza in bourgeois ‘small talk’. She learns completely meaningless phrases by heart, which she is to offer up at Mrs. Higgins’ tea party, thus deceiving the other visitors about her true social class. In a splendidly comic scene, Liza sticks to the topic of weather and illness, but her need for meaningful conversation overwhelms her and she falls back into her own speech. While this delights Freddy, it somewhat disturbs his mother and proves, for the time being, that Liza has failed this test. Liza, who is used to saying things of substance, is quickly ordered to leave by Higgins as everything threatens to get out of hand.

The evening after Liza has actually persuaded society she is a duchess, Higgins treats her like his servant. This enrages her as the consequences hit her: “What’s to become of me?”. Now she realises with full force what had been troubling the older women from the beginning: “What am I fit for? What have you left me fit for? Where am I to go? What am I to do? What‘s to become of me?” When Higgins suggests she could marry, she responds with great insight:

“We were above that at the corner of Tottenham Court Road. (…) I didn’t sell myself. Now you’ve made a lady of me I’m not fit to sell anything else. I wish you’d left me where you found me.”

For Higgins, Liza is property. She now realises: “Aha! Now I know how to deal with you”, she says and regrets not having realised before how she could defend herself (by teaching phonetics).

Liza displays in this play a profound humanity, which arises from her working-class background and her experience as a woman. Towards the end of the comedy, when Higgins asks her about her suitor Freddy, who writes to Liza several times a day: “Can he make anything of you?”, Liza counters this insult with an answer that Higgins couldn’t even conceive of: “Perhaps I could make something of him. But I never thought of us making anything of one another; and you never think of anything else.” Liza has a far greater degree of humanity and insight than any middle-class character in the play, and added to this is her sense of equality.

Another example of Liza’s generosity towards others: Her father discovers that Liza is in Higgins’ house: because she “took a boy in the taxi to give him a jaunt. Son of her landlady, he is.” Mrs Pearce also displays dignity, a sense of responsibility and humanity. She too acts class-consciously and keeps Higgins in check, to a certain extent.

For all these reasons, we must agree with Shaw when the false happy ending of conventional comedy, a marriage between Higgins and Liza, is out of the question for him. It is precisely his understanding of class and the class conflict that do not permit such an ending. Shaw thus breaks with the convention of comedy. That which the audience is conditioned to expect does not occur. Shaw subverts this expectation and holds up a mirror to the mainly bourgeois English audience to raise their doubts and shake their complacent sense of superiority. The play ends with Liza’s departure and Higgins’ unreformability. It is abundantly clear in this context why any suggestion of a happy ending in the later Pygmalion-based musical My Fair Lady is such a betrayal of Shaw, while Willy Russell’s drama Educating Rita is more in his spirit.

What does the play have to do with Ireland? When I asked my students this question, they answered that the Irishman Shaw clearly comments on the situation of the Irish in two respects. Their pronunciation marks them as colonised and second-class citizens – with an Irish pronunciation one could not get anywhere in the England of his time, perhaps not even today. Although himself a member of the ruling Protestant ascendancy in Ireland, Shaw clearly identifies with the class to which his heroines here belong and makes clear the strength of that class. He does so as a socialist, yet as an outsider. He can only grasp working-class representatives, their dignity and strength from the outside.

At the same time, his fellow Irishman, the painter and decorator Robert Noone (Tressell), also born in Dublin, wrote The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, the first working-class novel in English-language literature.