This most bloody and divisive prime minister: Margaret Thatcher, exploitation and class struggle

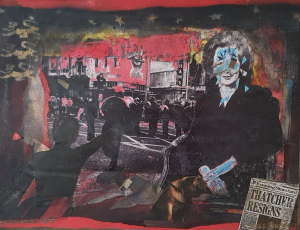

Fran Lock writes about Thatcher and her legacy. Image above: Steev Burgess

Not quite a decade after her death, and already cultural depictions of former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher are everywhere in evidence, most recently in the hit Netflix TV series The Crown, where she is played by Gillian Anderson. Anderson's portrayal is by no means flattering; it has, in fact, received a great deal of vitriolic backlash from the right-wing press. Good. Except the problem of representing this most bloody and divisive of prime ministers goes far beyond the degree of sympathy with which she is characterised. It has to do with what happens when we translate political figures from the muck and mess of immediate history into slickly produced packages of self-contained narrative. It has to do with what happens when the pain of living memory becomes popular entertainment.

Where Thatcher is concerned, there is so much pain, persistent pain. One significant discomfort I have with The Crown and with similar docudramas is that it relegates the events of Thatcher's tenure to a finite and clearly delineated past, when the horrors she inaugurated and presided over are not, in any meaningful measure, 'finished'. As an example, we might consider Orgreave and Hillsborough, and the long and difficult struggles for justice endured by those affected.

The violence that took place at Orgreave was not merely the worst example of police brutality ever witnessed in a modern industrial dispute; it was the culmination of a concerted campaign on behalf of Thatcher's government to diminish the strength of the trade unions. In the years before Orgreave the Conservatives had planned to face and to defeat a strike by the NUM, or by another of the mass-membership unions; to that end they had inextricably allied themselves with the police, awarding pay rises for officers, while workers in nationalised industries were forced to live at the sharp-end of redundancy and privatisation. In the wake of the violence, where mounted police charged protesters, attacking them without justifiable provocation, Thatcher's private secretary wrote to a Home Office official that 'The prime minister […] agrees that the chief constable of South Yorkshire should be given every support in his efforts to uphold the law.' A note by her policy advisor, David Pascall, expresses a similarly swift and absolute judgement, describing the miners as a 'mob' and as 'Scargill's shock-troops'.

Police brutality

The legitimation and bolstering of police brutality as policy could be said to lead inexorably to events at Hillsborough. In not holding the South Yorkshire police force to account for Orgreave, in frustrating inquiries into police violence, and in refusing to implement reforms, Thatcher's government saw Peter Wright, the chief constable who had overseen the operation at Orgreave, still in charge some four years later. Wright was responsible for appointing David Duckenfield to police the match at Hillsborough, and for heading the campaign to deny responsibility for the disaster, blaming and slandering the victims. The treatment of football supporters at Hillsborough was given official sanction by the brutal policing of the miners’ strike. It is all connected, and the search for justice and accountability is ongoing. The repercussions ripple out for years, across generations. The complexity, specificity, and interrelatedness of this pain is not easily accommodated within the docudrama format, which relies heavily on resolution within neatly determined narrative arcs.

An even greater level of unease exists for me around the issue of focus. The Crown and similar shows are top-down dramas: we see the subjective effect of the decisions Thatcher made upon herself and her immediate circle. We do not see the wider consequences of those decisions for the thousands of people who suffered them, or we see those consequences only in the broadest possible brush strokes, and not with the nuance and granular particularity of real experience. This creates a vague nostalgic haze around events such as the miners' strike or the invasion of the Falkland Islands. These are cultural milestones, they feel known, but they are little understood; they have become the depoliticised stuff of zeitgeist, emptied of content and of true human cost.

The screen transmits personality, it cannot credibly render the difficult and shadowy reasoning of ideology, which is where Thatcher's murderous toxicity truly lived. How can an actor hope to convey this through gesture and tone, within the limits of an accessible light-entertainment script?

They can't, and so viewers are either hoodwinked into a sympathetic identification with the Thatcher 'character', or they may come to relish Anderson's performance as a kind of cartoon Ice Queen, an exaggerated parody of awfulness. At a cultural moment where the line between politics and entertainment is already dangerously blurred, and where political careers rise and fall on the strength of 'personality', this should give us pause. Yes, politicians are people too, but it isn't who they are as human beings that is relevant to us, it is what they do. Learning to read politicians as characters, and political careers as stories of individual exceptionalism, of private triumph or failure, is a disturbing trend with grave implications for our future as voters and citizens.

The Ballymurphy Massacre

This has been much on my mind of late. The recent conclusion of the long-awaited inquest into the Ballymurphy Massacre has had me thinking about hidden continuities of state violence. Mrs Justice Keegan delivered a savage indictment of both the British army's actions and the subsequent state-sanctioned efforts to depict the deceased as IRA members. The attack in 1971, is one in a long line of historical injustices that are only now, after decades, beginning to be addressed, including those that took place during Thatcher's tenure.

In particular, I have been thinking about the atrocities carried out by the notorious Glenanne gang, to which is attributed some 120 murders. The Glenanne gang were an informal alliance of ultra-loyalist groups, run with the collusion of the British government. It comprised roughly 40 men, including members of the British police (the RUC), British soldiers, and paramilitary groups such as the UDR and the UVF. When the inquest into the Ballymurphy Massacre reported, the papers made their usual noises about how the findings could pave the way for prosecutions of armed forces veterans for historical abuses in the North of Ireland. Government and armed forces spokespersons were quick to shout down any such suggestions, highlighting once again the statute of limitations that covers both members of the occupying British forces and paramilitary groups. The argument being presented is that such a statute of limitations is fair to 'all sides'. It is not. There is an enormous difference between those actions carried out by local paramilitaries, and by those of an occupying nation state. And with regards to collusion with loyalist groups, the British government clearly has much to lose should the extent of that collusion become known.

What these reflections reveal, I think, is that history is still being made; that it is in a continuous process of painful negotiation and discovery. For that reason there would seem to be a greater duty of care attendant upon the treatment of recent history in art and culture. This kind of careful and pressured attention is something lacking in the mainstream media's recent depictions of Thatcher. Depictions in which her flawed humanity becomes the only necessary apology for the violent racism, classism, and homophobia of her politics, or in which she becomes a sort of grotesque scapegoat: the embodiment of the worst excesses of neoconservative ideology. Thatcher didn't happen out of air; the ideas she instituted did not disappear in a puff of smoke as soon as she was out of office. Look at Tony Blair and Keir Starmer. Her legacy is a living one, as viscerally present as it is vile. Look at the North of Ireland, and the blatant disregard for Irish life that Tory Brexit has exposed. Look at the victims of police brutality and their families, still waiting for justice after all these years.

The poems I want to present address themes around Thatcher, exploitation and class struggle. Unpacking a language for talking about the trauma of Thatcher and Thatcherism will take time and effort, but these poems, with their meticulous attention to sound and to the texture of particular, lived experience are a vivid and important beginning, a necessary counter-narrative.

The day she died

By Kevin Patrick McCann

There were fireworks,

Dancing in the street,

Ding-dong the witch is

Dead blasting out of stereos

But I stayed in our house,

Curtains closed

Remembering

That day they went back,

All brass bands and banners,

Lives in flinders,

Faces clenched like fists

Remembering

How she closed down the mines

And him sat in that chair

For weeks at a stretch

His thousand yard stare

At the end.

So no, I didn’t join in.

Just sat here alone.

Remembering.

they want all of our teeth to be theirs

By Martin Hayes

they want from us total commitment

they want from us our blood and our hunger

they want our flesh

inked with the company’s logo on our chest

they want our knuckles to our brains

and all the nerve-ends in between

switched off

they want our sinews and our muscles

sewn together with steal thread

so that we can only move

when they pull their levers

they want all of our teeth to be theirs

so that we can only chew when they chew

ache when they ache

they want us to show them where we keep our guts

so that they can sneak in under the radar

and pull them apart

angry thread by angry thread

until nothing is held

or stitched together anymore

they want us like robots

sat at our workstations every day

not wanting or able to think

of anything other than what their virus

has burrowed into us

and malfunctioned us to think

and what do we want?

we want to be able to walk through the park on a Saturday afternoon

without feeling anxious

we want to be able to lay out on the grass

drinking ice cold beer

while looking up into the sky

without worrying about office politics

we want to swim in the ocean once a year

and know how we are going to pay for it

we want a mouth full of teeth

that we know we can afford to get fixed

or capped

if ever they should go rotten

we want to be able to enjoy the laughter and song

that comes from having food in the fridge the electricity bill nearly paid

a car taxed and full of diesel

a medicine cabinet full of floss sticks and Sudocrem

paracetamol and hand cream

Bonjela hair bands

Diazepam and Ansol

we want to be able to live in our block

without the threat of being redistributed

hanging like thick drool dripping from a councilor’s panting mouth

because an entrepreneur took him for a £500 dinner

and promised him a place for his kid in the prep school

that will take our council flat’s place

alongside the £65-a-month gym business units

and 1.5 million-pound lofts

we want to feel

be able to say to ourselves

that we are human

and not have to give everything of that away

just so we are allowed to work

just so we are allowed

to exist

Milk Snatcher

By Julia Bell

Father thinks she’s great. He tells us so at tea.

He enjoys the nightly news where rabbles

of dirty miners have it handed to them.

These Marxists with their utopias, need to get real.

She is bringing back stability, certainty,

to a hairy country, old and badly clothed,

with naïve teeth and a childish sense of

pageantry. She is telling us

who we are again. And even those

most disinclined to listen to a woman,

love her matronly, no nonsense ways,

and the righteousness of her hair.

I do not like her, and I do not understand

why she is so popular round here.

Jesus said we should love the poor,

not tut at them on the news.

I will live long enough to know that

I am witnessing the slow death of South Wales.

The sick, sliding slag heaps becoming

deep valleys of generational despair.

I have started blushing every time I get upset

and at the tea table I wear a NUM badge sent to me

by the miners, my cheeks on fire. I wrote to them after the news.

Father thinks it’s the funniest thing he’s ever seen.

Kevin Patrick McCann has published eight collections of poems for adults, and one for children, Diary of a Shapeshifter (Beul Aithris), a book of ghost stories, It’s Gone Dark, (The Otherside Books), and Teach Yourself Self-Publishing (Hodder) co-written with the playwright Tom Green. He is also the author of Ov (Beul Aithris), a fantasy novel for children.

Martin Hayes has worked in the courier industry for 30 years. His latest collections are Ox, published by Knives Forks and Spoons Press, and Where We Get Magic From, published by Culture Matters

Julia Bell is a writer and Reader in Creative Writing at Birkbeck where she is the Course Director of the MA Creative Writing. Her work includes poetry, essays and short stories published in the Paris Review, Times Literary Supplement, The White Review, Mal Journal, Comma Press, and recorded for the BBC. Her most recent book-length essay Radical Attention was published by Peninsula Press.

This article will also appear in the next issue of Communist Review.