How corporate media downplays climate destruction: Part One

Dennis Broe, in the first of to articles, describes how corporate media in all its forms downplays climate destruction. Above: New York skyline, with soot

Fredric Jameson’s famous dictum that “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism” has been taken up wholeheartedly by the makers of corporate television. In numerous series stretching across different genres and now accounting for its own genre – “post-Apocalyptic TV,” – broadcast, cable and streaming TV (and of course numerous films) have concocted a plethora of “endings” to the world as we know it which have the effect of failing to challenge the climate apocalypse, which would mean immediate action in the present to keep the worst from happening.

In so doing, the makers of corporate TV, largely American but then picked up across the globe using the American prototypes, have found a new way forward in the persistent refusal to challenge the fossil fuel industry that is a more sophisticated approach to the now mostly discredited “climate denial” narrative initiated by that industry. For if the catastrophe is unavoidable, we may as well begin planning for the post-Apocalyptic future. In the industry these are referred to as Dystopian Series but that is similar to calling climate destruction climate change, it’s a carbon-neutral way of labelling the problem without discussing it.

David Harvey reading Marx’s Grundrisse

This paper highlights the shift from apocalyptic series, which focus on the moment of the end times of the earth, and might be politically more useful, to “Post-Apocalyptic” Series, where the endpoint of destruction has already come and gone and the series is about coping with the aftermath in the best way possible. That is, the genre, for the most part, as David Harvey utilizes these terms borrowed from Marx’s Grundrisse, “presupposes” the end as at this stage inevitable and is about “positing” how to survive after the end, once the presupposition of end times is established.

The material reasons for the preoccupation with apocalypse at this conjuncture are the destruction of the earth, the escalating danger of nuclear war and the decline of the West, all of which is accompanied by a resolute repression in the corporate media which either refuses to engage or downplays the implications of any of these conditions.

However, this also allows for an opening. Whereas, in series based in the present, political content is mostly abandoned or repressed, these series, once the idea that the end time is not nigh but here, may allow a freedom for both pursuing a deep critique of the contemporary order and a positing of alternative orders.

In Season 11 of The Walking Dead, the originator and dean of this genre, the problems of the present resurface, as the neoliberal “perfect world” of The Commonwealth conceals a vicious and violent inner core, a repressive deep state needed to maintain the surface air of gentility.

The Last of Us presupposes at its outset a fascist government, the endpoint of today’s neoliberal experiments as the French, no longer believing in Macron as a bulwark against fascism, since he has used undemocratic techniques himself, now turn to Le Pen. However, in the course of the cross-country travels of the two lead characters, the series posits the creation of a communal compound which is the opposite of this order and which opposes it.

Finally, the class antagonism in Snowpiercer indicates that the post-Apocalyptic world cannot escape the problems of the present, perhaps negating or qualifying the effectiveness of this flight into fantasy, while also suggesting, in the most radical positing of the genre, that a world shorn of capitalists can negotiate its own resurrection.

Oil I Want Is You

“The best thing about the Earth is, if you poke holes in it, oil and gas comes out.” — Republican U.S. Congressman Steve Stockman, 2013

Climate activists denounce COP28, the oil-friendly climate conference

We are all witnessing the increasing failure to confront climate catastrophe and to rein in the fossil fuel industry, with the next global conference on climate, COP28, being held in the oil rich city of Dubai, chaired by the head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company which is investing billions in pumping more oil next year. It is no wonder there are calls to boycott the conference. With this capitulation depictions of the end times have increased.

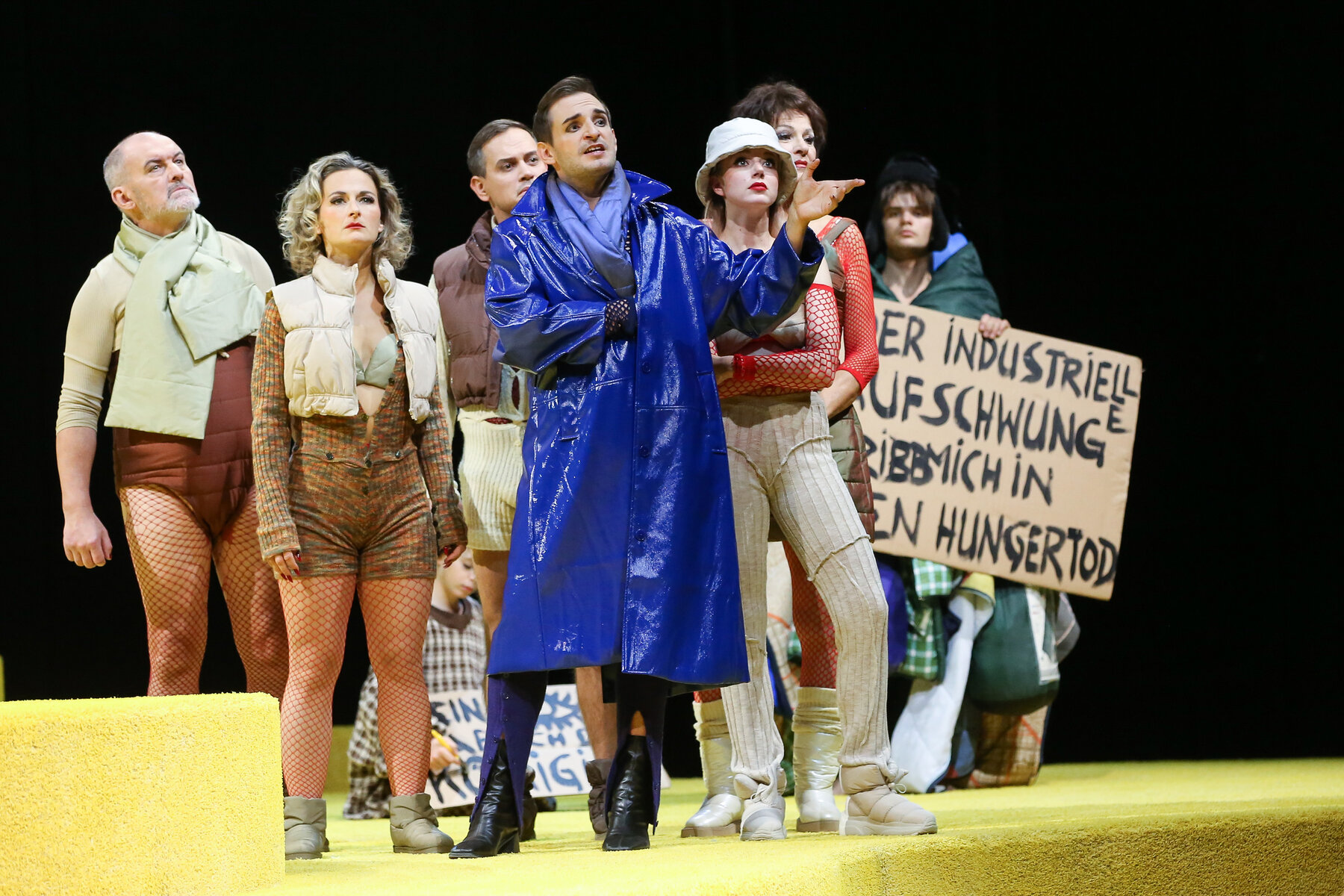

At this year’s Series Mania, the largest television festival in the world held at Lille in France, apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic series had, along with Me Too female liberation series, become the dominant genre, accounting for 13 percent of the total of 55 series. These included the apocalyptic tone of the endpoint of Western science in Lars Von Trier’s return to The Kingdom; South Korean high-school teens training for an alien threat that hovers over their heads in Duty After School; the Spanish series Apagon where a solar tempest strikes the earth; The Fortress, where Norway, in Trump-style, walls itself off from the world and then must confront a deadly virus; and finally The Swarm, a global series financed by several European public television networks in which the ocean sets out to wreak its revenge on a humanity bent on destroying it.

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has set the Doomsday Clock at 90 seconds to midnight, as planetary destruction looms. This grim future reality though is belied by a most abundant present for oil and gas companies whose profits have never been greater.

Largely as a result of the energy crisis because of the war in the Ukraine, the profits of the five largest producers of oil and gas, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Shell, BP and Total, were $195 billion in 2022, almost 120 percent more than the previous year and the highest level in the industry’s history with the U.S. President Biden accusing these companies of “war profiteering.” Only five percent of these profits went to developing clean energy, with the majority going as Chevron claimed to “shareholders, investing, and paying down debt.”

The war has also occasioned a return to the most dangerous and most polluting methods of extraction, including in the West deepwater drilling and the return of coal, and across the world new nuclear power plants have been announced in Malaysia, Indonesia and The Philippines. Meanwhile France threatens to bring 6 to 14 new plants on line, regardless of the nuclear waste these plants will generate.

In the U.S., now the largest supplier of natural gas, this has meant a return and reopening of the previously unprofitable industry of fracking in a new narrative where this process, which destroys drinking water and leaks methane in a way comparable to coal mining, “saved American democracy.” The day the war began the Bloomberg News Agency ran a story headlined “Fracking: A Powerful Weapon Against Russia,” trumpeting the return of an industry that had almost gone bankrupt.

The carbon imprint of the replacement of Russian oil and natural gas with American fracked gas, with its increased transport distance is twice as great as before. Add to that the imprint of American hydraulic fracking and the carbon imprint is almost three times greater.

In addition, the war has also seen the blowing up of the Nord Stream 1 and 2 Russian pipelines, with the culprit still an object of surmise but with much of the evidence, as marshalled by the U.S. Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, leaning toward the U.S. and Norway, oil producers who have been the major benefactors of the sabotage. The methane emitted from the cloud that passed across Europe was described as described as “the highest release of methane gas ever on the planet.”

The failure to confront the fossil fuel industry

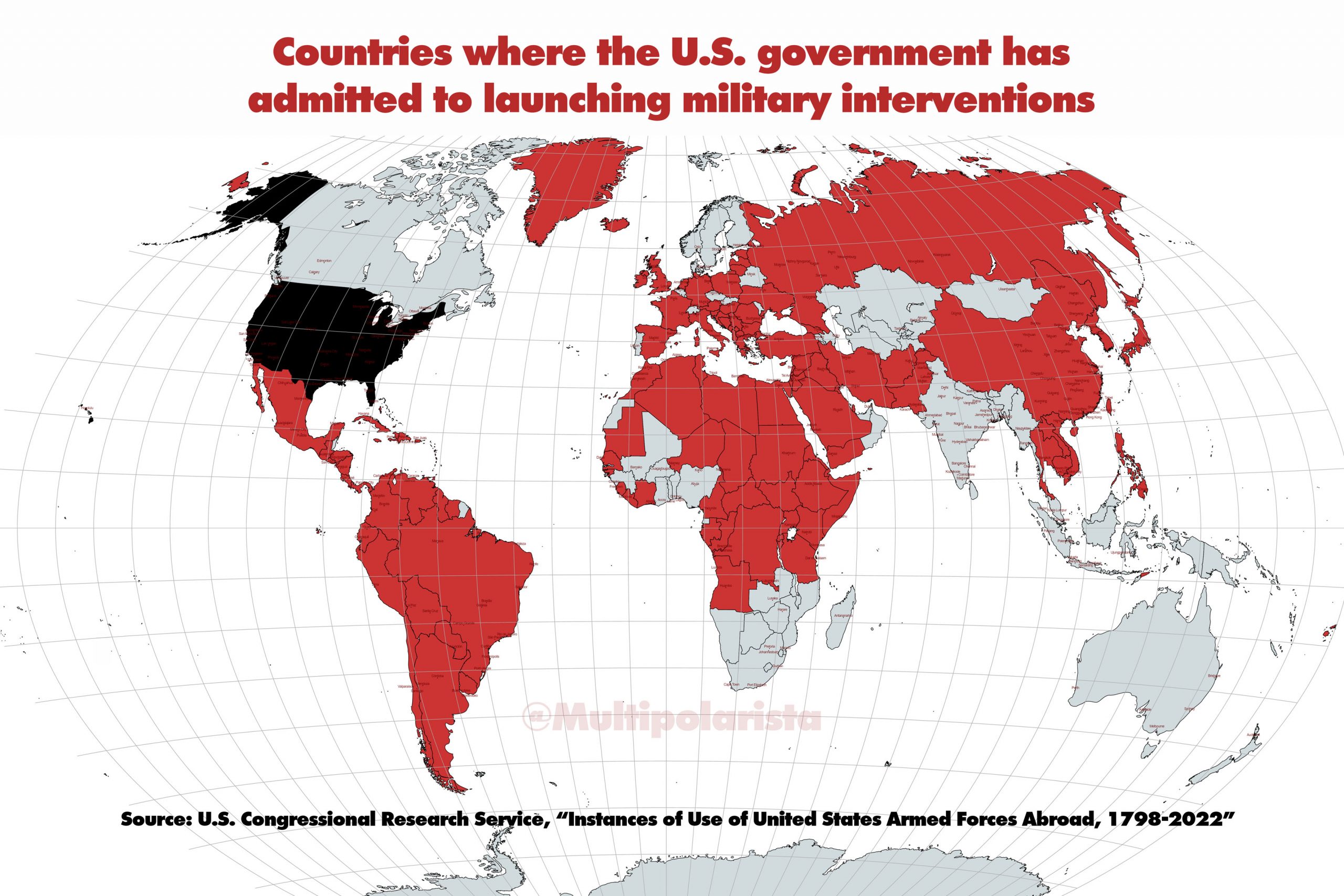

Since the onset of the war, Western governments have caved into the demands of an ever more dominant and omnipotent fossil fuel industry with the U.S. president Biden having implemented all the policy requests of a secretive fossil fuel lobby group, just as Bush in a secret meeting never made public signed on to Cheney’s Haliburton agenda, and as Trump more brazenly named the head of Exxon as his secretary of state. Equally, European leaders have met more than 100 times with the industry since the war began, while industry lobbyists at 2002’s U.N. climate conference far outnumbered “climate-vulnerable African countries and Indigenous communities.”

The effects of this onslaught have already appeared in the U.S. in rising coastal sea levels in the East amid worse hurricanes and storms, Midwestern mega rains and droughts destroying crops and homes, and worsening and more destructive forest fires in the West. The apocalyptic effect by the end of this century if this destruction is not halted will be the drowning of island nations, the inundating of coastal areas from Ecuador to Brazil to the Netherlands as well as huge swathes of South and Southeast Asia and the potential extinction of major cities, such as New York, Los Angeles, Vancouver, London, Mumbai and Shanghai.

All of this is linked to the failure to confront the fossil fuel industry. As Naomi Klein says:

“We have not done the things that are necessary to lower emissions because those things fundamentally conflict with deregulated capitalism. The actions that would give us the best chance of averting catastrophe…[threaten] an elite minority that has a stranglehold over our economy, our political process, and most of our major media outlets.”

All of this in terms of the apocalyptic imagination leads to “the acute and painful realization” that our “leaders are not looking after us . . . we are not cared for at the level of our very survival.”

Nuclear war and imperial malaise

There are two other forms of destruction on the horizon and which also are essentially going largely undiscussed and unheeded. These are are the (renewed) threat of nuclear war in the face of the ever-escalating war in Ukraine and what I will call, after Paul Gilroy, ‘imperial malaise’, the decline of the West, which is being hastened by the division of the West and the rise and resistance of the rest of the world prompted also by the war.

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament poster

With Russia having announced the stationing of nuclear weapons in nearby Belarus and with the NATO countries continuing the path of escalation (the British supplying depleted uranium weapons which will leave radiation traces on both the Ukrainian users and the Russian targets while destroying swathes of the environment, the Germans sending Leopard tanks east in an ominous suggestion of World War II and with Poland now demanding to be armed with U.S. nuclear weapons) and as the U.S. secretary of state declares that the U.S. will support no peace talks and will not end the war, the threat of a full-scale nuclear war increases daily. This threat, mostly unacknowledged in the corporate press, also feeds the feeling of hopelessness and a sense the world may be coming to an end.

From Apocalypse LA

The failure of the West, led by the U.S., to enlist the rest of the world in its campaign against Russia, with fully 83 percent of the world refusing to go along with U.S. sanctions, has hastened an already accelerating decline, as the centre of economic activity shifts eastward to Asia. The results have been a cumulative apocalypse which has seen income disparity worsen to the point where the creators of these television series, the Hollywood writers, claim as a primary reason for their strike that they can no longer support themselves on their salaries while profits within the streaming industry soar.

In France inflation from price gouging and the war, the raising of the retirement age and the cancelling of job security is expressed in graffiti on the Left Bank that simply states “greve ou creve,” strike or die.

Finally, there is the crisis of the drug epidemic, as a way of coping with this destruction, that has passed from heroin to Purdue Pharma distributed oxycontin to fentanyl, seven times more potent and addictive than heroin – all three discovered and originally manufactured in Big Pharma laboratories – making the streets of Los Angeles unsafe. It’s no wonder that one of the contemporary Hollywood apocalyptic series From has everyone locked in their homes at night, with living dead, flesh-eating zombies ready to devour anyone who lets their guard down and goes outside.

The full weight of these various apocalypses is never registered in the continuing onslaught of corporate media where we are told that despite it all, the system is coping, doing its best and is still the hope for humanity. The cognitive dissonance and distance between what is said and what the collective unconscious knows to be true but which must remain unsaid is also responsible for the dominance of the terrifying images of post-apocalyptic television.

How can it be, for example, that a country which holds itself up as a shining beacon to the world, sometimes called “the indispensable nation,” supplies B-16 bombers to Ukraine at $550 million per plane but forces its homeless in Los Angeles, epicentre of a national housing crisis, to sleep at night on public buses?

Part 2 will describe various apocalyptic TV series as both promoting and contesting climate destruction.