Robert Ballagh's 'The Thirtieth of January' and Bloody Sunday, 1972

Jenny Farrell gives the background to Robert Ballagh's new painting, marking the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday

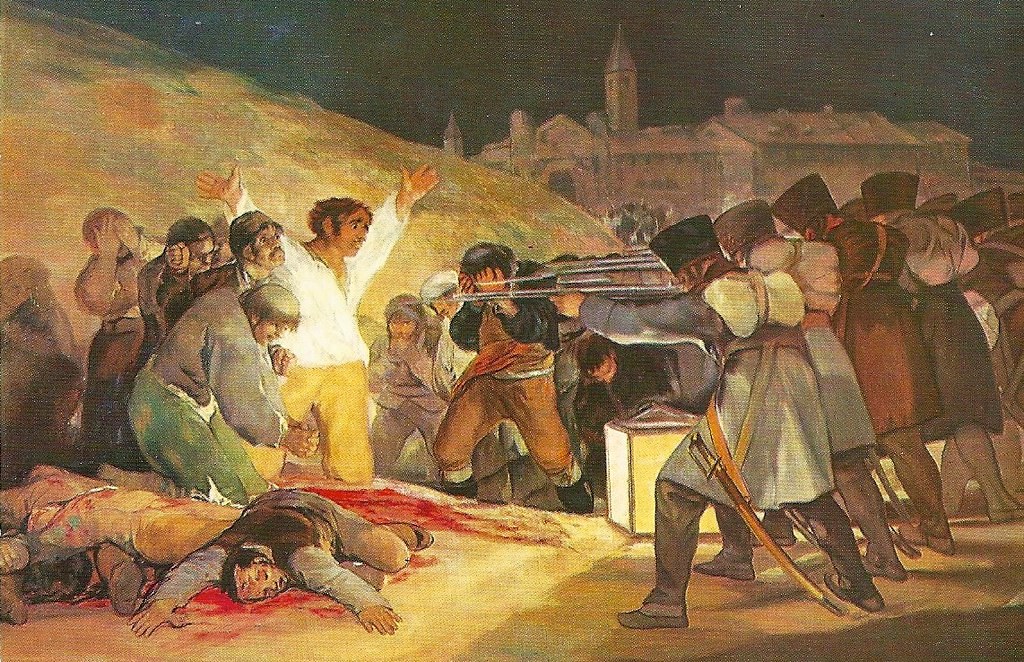

When Robert Ballagh, the outstanding contemporary Irish painter, found a growing need to mark the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, he felt more and more drawn to paintings that had impacted on him in the past. The most compelling one in relation to the Derry massacre was Goya’s The Third of May (below), a painting depicting the execution of Spanish people on Spanish soil by the invading French army.

Ballagh’s painting is entitled The Thirtieth of January. The parallels in the situation are clear: On Bloody Sunday, Irish people were executed on Irish soil, by British soldiers.

Bloody Sunday, 30th January 1972

Bloody Sunday was a turning point in the North of Ireland conflict. It broke the civil rights movement, which in the late 1960s had highlighted internationally the sectarian, repressive Unionist regime by peaceful demonstrations, demanding equal rights for Catholics.

On 13 August 1969, the British Labour government had brought British troops onto the streets, initially to stop sectarian gangs, but then, aided and abetted by the police, attacking nationalist communities in Nazi-like pogroms.

In June 1970 the Tories came to power with Edward Heath as Prime Minister, and the British state took on a menacing role. The Tories (the Conservative and Unionist Party) were allies of the N. I. Unionist Party, that had controlled the sectarian state since its establishment in 1921. This led to a surge in repression of the Catholic community, culminating in internment without trial in August 1971.

During the introduction of internment, the First Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (1Para) shot dead ten residents, including a mother and a priest, in the Ballymurphy Massacre. A plan drawn up in London by the highest government circles was aimed at crushing resistance through acts of “collective punishment” of the Catholic community in the North of Ireland.

A civil rights demonstration was called for in Derry on 30th January 1972, which demanded an end to internment. The agreement between the chief constable in Derry and the Northern Ireland Civil Rights organisation (NICRA) had been that the peaceful march would stay within a Catholic area. The IRA had also made clear there would be no armed presence on the day.

Increasingly, the British Tories and their Unionist allies had been incensed by the existence of “Free Derry”, a Catholic residential area of the city that had become a no-go area for the British security forces since the pogroms of August 1969. It was here the civil rights demonstration was set to take place. It was later claimed that an attack on such a demonstration was expected to lead to a direct confrontation between the shock troops of 1Para and the IRA, and result in “Free Derry” being subjugated. If this plan failed to materialise then the demonstrators, who were deemed by the British high command to be part of the enemy, could be taught a lesson. And so the massacre in Derry was planned by Heath and high-ranking military. A 16-soldier-strong company of 1Para was responsible for all the shootings on the day. It included the same soldiers who had been blooded and commended for the Ballymurphy Massacre.

A number of inquiries into Bloody Sunday followed, none of which led to a conviction of those responsible. Although the evidence against the military was overwhelming, only one paratrooper, “Soldier F” was initially charged 49 years later with murder of two of the fourteen dead on Bloody Sunday, and then the charges were dropped. The same “Soldier F” had received a commendation for his role in the Ballymurphy massacre. Currently the British government is pushing through an amnesty for all those guilty of murder in the North of Ireland in an attempt to stop once and for all the possible prosecution of their military and associated killer squads.

This inability of the British judiciary to deliver justice in such blatant cases has acted as a weeping wound in Ireland. Several of Ireland’s best artists have taken a stand in their work, including Thomas Kinsella, Brian Friel, and Robert Ballagh.

The title of Robert Ballagh’s painting, The Thirtieth of January, makes in itself clear the connection to Goya’s The Third of May. But of course the visual language is compelling. While in Goya’s picture, the outline of Madrid sets the location of the executions in 1808, in Ballagh’s it is the Derry skyline, its walls, St Columb’s cathedral, the Presbyterian church and indeed with Walker’s Monument still in place, which was blown up in 1973. Where there is a hillside behind the Spanish victims on the left of Goya’s picture, in Ballagh’s painting the eye moves upwards from the Bogside to working-class terraces.

In both paintings the focus is on the victims, the people against whom and on whose territory the atrocity is being committed. They are the figures whose faces we see – the soldiers are faceless. While Goya chooses the moment of execution of the central rebel (others already lie dead beside him), Ballagh depicts a scene directly after the shooting has started. He shows us two victims, one dying, the other dead. Looking at the picture, we are faced with a group of distressed people running towards us, a press image that went around the world. Father Daly is holding up a white bloodstained handkerchief, trying to shield this group carrying the first victim of the massacre, the mortally wounded Jackie Duddy, out of range.

These people are clearly recognisable. They also hold white bloody handkerchiefs, underlining a peaceful protest crushed in blood. In Goya’s painting, too, a monk is by the side of the rebel, offering support, along with others. In addition to this, another priest, Father Hugh Mullan, had been shot dead in the Ballymurphy Massacre. So there are many layers of associations in this figure.

Centred in the foreground is another victim, covered in a white bloodstained cloth, echoing the handkerchiefs. The stark white, associated with peace, innocence and martyrdom, reminds viewers of the brilliant white shirt of the man about to be executed in Goya’s painting. He is flanked on the right by a group of faceless soldiers, their weapons by the hip indicating indiscriminate shooting without aim. Another solder on the left in a kneeling position closer to the body suggests “Soldier F” who knelt to shoot dead Barney McGuigan, as he waved a white handkerchief high above his head, trying to go to the aid of the dying Patrick Doherty. “Soldier F” was responsible for a number of the cold-blooded killings, and the sole soldier to be accused of murder, only to be cleared later.

Ballagh makes clear that the marchers were unarmed. We see two placards on the ground reading “Civil Rights Now” and “End Internment”. A Civil Rights banner occupies the upper centre of the picture, like a title.

The painting not only references Goya, but also Picasso’s Guernica, itself a picture about foreign invaders murdering a native population and inspired by Goya. Like Picasso, Ballagh decided on a monochrome painting. The covered dead man’s hand in the centre foreground still holds the broken end of the “End Internment” placard in his right hand, in much the same way as the slain man in Picasso’s painting grasps the broken sword. The left hand also echoes Picasso’s in its reach towards the left corner of the painting, as well as in its gesture. Picasso and Ballagh’s black-and-white execution evokes newspaper images; in Ballagh’s case most of the press photographs and footage from the event were in black and white. The only colour are the blood red splashes on white. The smoke behind the silhouetted demonstrators in the background suggests the use of tear gas seen in so many photographs of police attacks on demonstrators.

In the left corner, under the foot of the kneeling soldier, we see a sheet of paper with the Royal Coat of Arms and writing on it. They are the words of Major General Robert Ford. The title is the massacre’s military code name, Operation Forecast, and is dated January 30, 1972. The text reads:

I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders amongst the Derry Young Hooligans.

Ballagh leaves no doubt but that the killings were ordered at the highest level. In this respect, too, the painting goes further than any Inquiry has ever done. Michael Jackson, a senior officer in command, was later promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the British Land Forces.

Art history and political history are connected. Art doesn’t exist outside of time, and there is a tradition in art that does not shrink away from a commitment to justice, to taking sides. Neither does this diminish the artist – think of Mikis Theodorakis and Pablo Neruda, and of course Goya, all of whom have produced work that has echoed through time. Goya’s painting inspired Picasso’s 1937 Guernica and the 1951 Massacre in Korea; it has also been an enduring influence on Robert Ballagh’s work.

The power of this work, through Ballagh’s interpretation, was picked up by a community art group in Derry who recently asked his permission to reproduce his The Third of May on a wall in Glenfada Park, one of the murder sites on Bloody Sunday. They did this because they could see the direct connection between the terror and the anger of their own experience and that depicted in The Third of May. In both pictures, the viewer is a direct witness to the events and, standing alongside the artist in the midst of this slaughter, feels involved.

Beside it, up until recently, the group had displayed their copy of Picasso’s Guernica. When artists take the side of the people against oppression, they resonate and are understood worldwide because the condition of the victims of wars for profit, power, and control is global. Bloody Sunday is a part of the world history of colonialism, occupation and people’s resistance, and Robert Ballagh’s painting expresses this insight, demonstrating the necessity of art.

Robert Ballagh's speech at the unveiling of the artwork

Well, it's a long, long time since I was standing here, inside the Guildhall. Believe it or not, in the early 1960s I was in a showband and we used to play at dancers here in the Guildhall. Can I say, it's great to be back! To my mind the 13th of August, 1969 is a truly significant date in recent Irish history.

Let me explain. On that date sectarian gangs, aided and abetted by the police, made violent incursions into nationalist communities, burning houses and driving people from their homes. The response was immediate; widespread rioting broke out and the British government took the precarious decision to deploy troops onto the streets of the north. At the time the British home secretary James Callaghan ruefully observed: "It was easy to send them in but it will be much more difficult to get them out!”

On the other hand the Irish government was caught completely unawares; successive governments having ignored the north for decades. Initially the Dublin government set up field hospitals and a few refugee camps to help those fleeing the conflict. A relief fund was established to alleviate the distress and a covert plan was agreed to import arms to be made available to northern nationalists in the event of a repeat of the sectarian attacks of the 13th august.

When the plan was rumbled, leading members of the government (including the Taoiseach, Jack Lynch) denied all knowledge and scapegoated Ministers C.J. Haughey and Neil Blaney who were summarily dismissed from their posts. Two arms trials followed which resulted in all defendants being found not guilty. The official reaction in the south to the unfolding violence in the north left many nationalists feeling that, in the future, they would be on their own.

In the visual arts response to the violence was triggered by a surprising intervention by the artist Michael Farrell. In 1969 the most important annual display of contemporary painting, the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, was due to open in Cork and then travel to Belfast. At the opening in Cork, on receiving his prize for the best painting in the exhibition, Michael declared that he was giving his prize money to the northern refugee fund and that he was withdrawing his picture from the exhibition in Belfast. Obviously Michael’s pronouncement provoked serious reflection by the rest of the artists in the exhibition. I was one of those artists and had been awarded second prize for a painting entitled ‘Marchers’. It was from a series inspired by the civil rights marches in America and the civil rights campaign in the north.

Eventually 10 artists including myself decided to follow Michael’s example and withdraw from the exhibition in Belfast. Some time later Michael informed me that he was planning to stage an exhibition of the withdrawn works in Dublin and that he had secured a venue in Kildare St., opposite Leinster House that was the HQ for an organisation called the Citizens Committee. I later learned that it received funding and support from the government's northern relief fund.

I agreed to help hang the exhibition but when I arrived at 43 Kildare Street I discovered that there was a scarcity of equipment. Someone suggested that I try the basement. Unfortunately there were no tools there only several large wooden crates. This discovery instantly provoked a panic attack because, at the time, the air was thick with rumours of guns being smuggled north. Subsequently I learnt that the crates contained not guns but radio equipment which eventually helped set up Radio Free Belfast and Radio Free Derry.

The opening of the exhibition was performed by Paddy Devlin who later went on to become one of the founders of the SDLP.

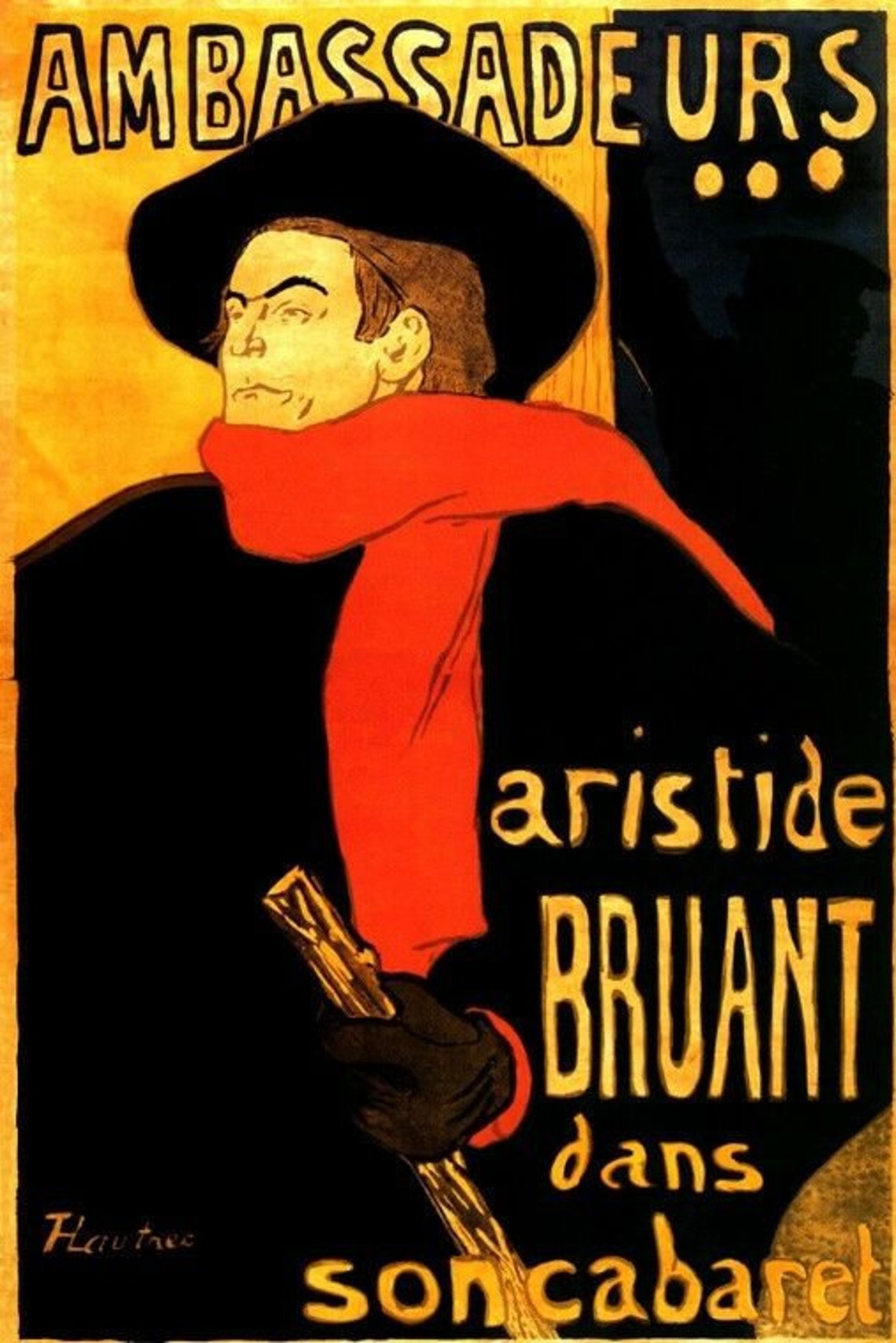

Michael asked me to design an exhibition poster featuring one of his paintings. Soon afterwards, however, I found myself faced with an awkward dilemma. I was invited to take part in an exhibition organised by the Arts Councils of Scotland, Wales, Ireland and Northern Ireland and since the last venue for the exhibition was Belfast I had to decide whether I should continue my boycott or perhaps try to make some relevant imagery. I opted for the latter. That was the easy part – the difficult part was what to do. I resorted to art history and scrutinised those artists who had responded to similar circumstances in their own time.

The first picture that stood out by a mile was The Third of May by Francisco Goya. In this painting Goya depicts an actual event in Madrid when occupying French soldiers executed Spanish patriots. Since I was acutely aware that I couldn't possibly improve on Goya’s masterpiece I decided to refrain from interfering with his superb composition and instead to simply paint it in a contemporary style which would hopefully bring it to the attention of a wider audience.

I did the same with Rape of the Sabine Women by Jacques Louis David which was his response to the internecine violence which occurred in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Eugene Delacroix also addressed the phenomenon and that was the French Revolution with his painting Liberty Leading the People.

I have to say I was disappointed by most reviews of my work in the exhibition as it toured Edinburgh, Cardiff and Dublin. Most critics dismissed my efforts as a hollow mockery of great art and certainly none we are prepared to acknowledge my desire to link art to the unfolding conflict in the north.

When the exhibition arrived in Belfast I hoped that, at last, someone might recognise the political content of the work. In those days the Arts Council of Northern Ireland had a gallery on Bedford Street in Belfast with the equivalent of a shop window. The exhibition officer Brian Ferran decided to hang Liberty Leading the People in the window. After the exhibition closed I called Brian to ask if there had been any public reaction. He told me that they received just one complaint. It was from a DUP counsellor. He was unhappy with the naked breasts on display. I have to admit that I was frustrated by the failure of many people to take on board what I was trying to say. So, some time later, I decided to paint a picture that would make my intention clear. I called it My Studio, 1969.

The year 1971 saw the introduction of internment without trial by the Stormont government. This proved to be a disastrous intervention as its implementation was largely one-sided and consequently lead to widespread civil unrest with demonstrations, rallies and protest marches.

One such march was organised for the 30th of January, 1972 in Derry. The decision by the British authorities to deploy the parachute regiment on the day, proved calamitous. As we know, 13 innocent civilians were shot dead. When news of the mass murder spread I recall the mood of the people becoming convulsed with rage at what had happened.

When a march to the British Embassy in Dublin was announced, my wife Betty, together with our daughter Rachel, who was only three at the time, and myself decided to make common cause with the protesters. I clearly remember the anger of the crowd as it moved through the city. Anything that could be identified as English was not safe. I remember hearing the shattering of plate glass windows as we passed the offices of British Airways at the bottom of Grafton Street. When the march reached Merrion Square it joined a large crowd that had already assembled in front of the embassy. It seemed to me that the mood of the crowd had shifted from anger to a hunger for vengeance. Initially stones and other objects began to fly in the direction of the embassy; next it was glass bottles but before long these had morphed into petrol bombs. At that stage I suggested to my wife that we quit the scene, since being responsible for a three-year-old in a possible riot situation was not ideal. Later we learned that we had missed the final conflagration but also, thankfully the violent chaos of a police baton charge that left many wounded in its wake.

Later that year the IECA took place in the Project Arts Centre in Dublin and several artists exhibited work that was provoked by Bloody Sunday. In it I chalk marked on the gallery floor the outlines of 13 bodies and then poured blood which I had obtained from a friend who worked in the Dublin abattoir over each victim. Later, as part of the same exhibition the artist and writer Brian O'Doherty, who was based in New York, staged a performance where he changed his name, as an artist, to Patrick Ireland in protest over the events of Bloody Sunday.

After the whitewash by Lord Widgery the poet Thomas Kinsella composed a truly powerful poem Butchers Dozen and Brian Friel responded to Bloody Sunday with his play Freedom of the City, which was set in the Guildhall.

Not long ago some young people from the Pilots Row Community Centre approached me to request permission to create a mural based on my painting The 3rd of May after Goya to mark the anniversary of Bloody Sunday. Naturally I told them to go ahead.

Finally, on completion, when they asked me to unveil the mural in Glenfada Park I did so on a cold wet January afternoon. I was unaware at the time that this experience had planted a small seed in my subconscious which only germinated as the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday approached. As I began to feel a compulsion to create a new picture the approach of the young people from Pilots Row determined my response.

Once again Goya's example became crucial. In his painting the central cluster of victims demands your full attention; consequently I decided to replace them with the iconic image of Father Edward Daly with those carrying the body of Jackie Duddy.

The soldiers in Goya’s firing squad are French soldiers on Spanish soil shooting Spanish people whereas, in my picture, the soldiers are obviously British soldiers on Irish soil shooting Irish people.

Another artist who influenced my approach is Picasso. His painting Guernica, created in response to the Nazi bombing of the Basque town of the same name, has always fascinated me and it was the monochrome nature of his composition that I adopted for my picture, except that I allowed myself one extra colour – red, to represent the blood spilled on Bloody Sunday.

In order to remind people that the march on the 30th of January was an anti-internment march I decided to include a broken placard inscribed ‘end internment’.

In my painting I wanted to point out that even though the Saville Inquiry accepted that all of the victims were unarmed and above suspicion so far no one has been proven guilty of any crime. Hence the inclusion of the statement by Major General Robert Ford.

A long time ago I received an invitation to speak at a rally in Guildhall Square after the Bloody Sunday 21st anniversary march. At the time I was both humbled and terrified as I had rarely spoken in public before. Consequently I took the invitation seriously and invested considerable effort in preparing what to say. On the day, a cold rainy one, I managed to get through the speech and, as a result, was relatively pleased with myself. That night I stayed with a local family and, the following morning, as I tucked into an Ulster fry, we were joined by two young family members. One asked, “What did you think of yesterday?” The other replied, “Brilliant, except for that fellow from Dublin – he just went on and on!”

So bearing in mind that particular admonition I will tax your patience no further. Thanks!