'So now yir tellt!': the life and work of Alex Hamilton

David Betteridge discusses the life and work of Alex Hamilton, 1949-2018. It is a companion piece to Jim Aitken's essay-obituary of Tom Leonard.

I

This is not a proper obituary, although it started out as such. It is more a “thinking-through-writing” kind of thing, trying to wrestle a meaning out of some confusion. My subject is my friend of forty years, recently deceased, the prolific and talented and largely unpublished author, Alex Hamilton, aka Sandy Hamilton (to those who knew him from childhood), aka S&eh? (to those with whom he exchanged emails, who shared his love of puzzles), aka Alex. Hamilton (with a precise or pedantic dot after the first name, as he sometimes signed himself), aka Alexander P. Hamilton (as inscribed on the brass plate screwed to his coffin, which, following his own instructions, was lowered into the ground without a word being spoken), aka Django Ross or Cordelia d’Amfreville (pen-names that he adopted, the first mainly for works where he explored the punning possibilities of several languages, the second mainly for erotica).

As an author, Alex is remembered, if at all, for being one of the contributors to a handsome paperback collection of prose and verse published in 1976 by Molendinar Press, Three Glasgow Writers. The other two contributors were Tom Leonard and James Kelman, whose careers as authors, and later as professors of literature, rose and rose, while Alex’s flat-lined, then declined. I have been trying to understand why the two succeeded, by all measures, while the other, my friend, failed.

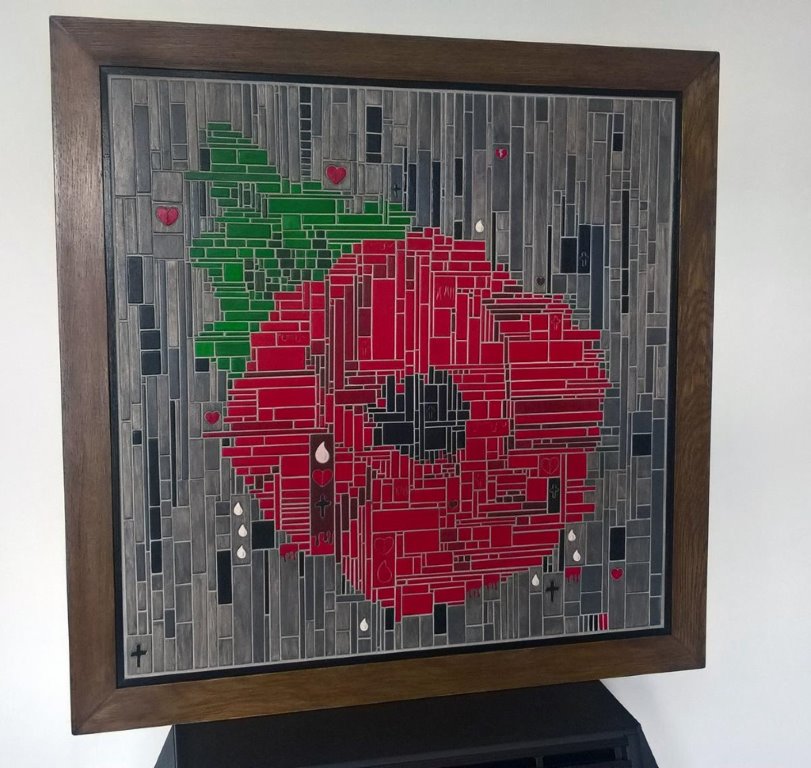

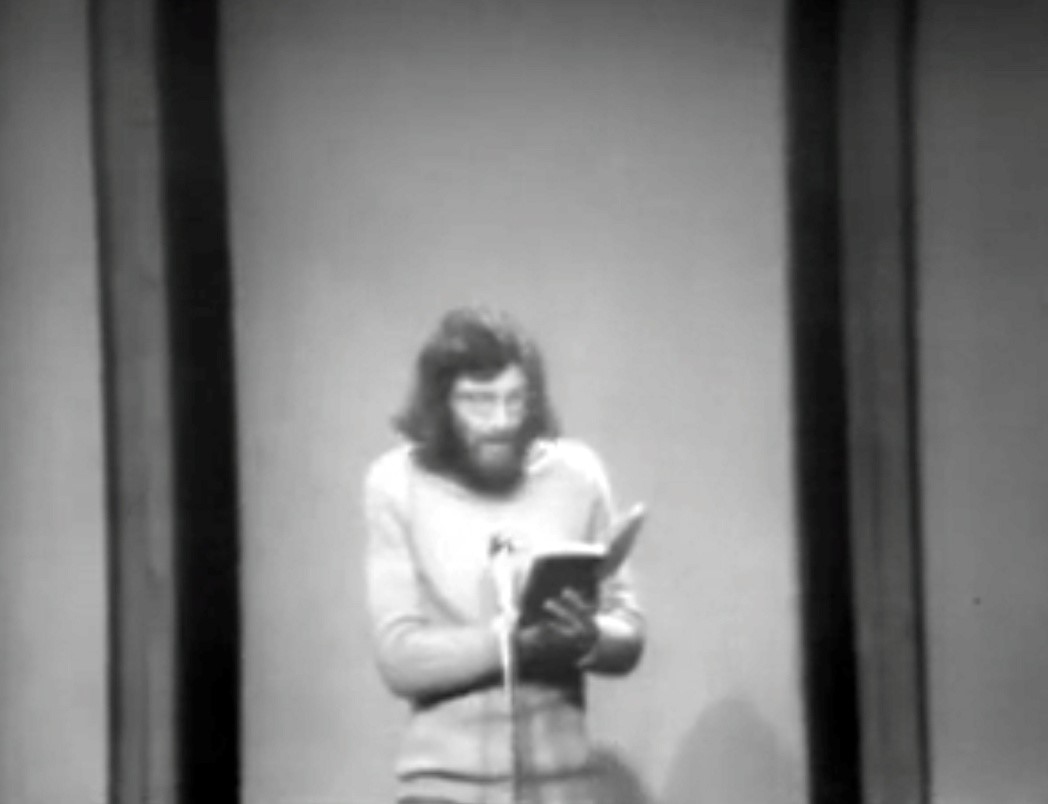

Alex reading at the Third Eye Centre, Glasgow, in 1976, at the launching - jointly with Tom Leonard and James Kelman - of Three Glasgow Writers, published by Molendinar Press. This still is taken from a video recording of the occasion, reproduced here by permission of the Contemporary Centre for Arts, Glasgow. (Ref. TE3/1976/117)

You can read Tom Leonard’s works and you can read works about him quite readily, whether in book form or online, as in Jim Aitken’s superb essay in Culture Matters, written a few weeks after Tom’s death, which came a few weeks after Alex’s. Even more readily, you can read James Kelman’s works and works about him, and you can go on reading them, as he is still alive, happily, and still producing noteworthy literature - witness his recent novel, Dirt Road. Alex’s works, by contrast, are hard to find, either because they were never published, or because they are tucked away in magazines e.g. Gutter, or are long out of print. It was not always so, however.

In 1981, three of us, Ian Murray, Adam Currie and myself, all friends of Alex’s, persuaded him to let us publish a selection of his short fiction, under our Ferret Press banner. With support from the Scottish Arts Council, this collection came out the following year, with the title Gallus, Did You Say? and Other Stories. In putting this selection together, we were able to draw on a pretty wide range of previously printed and/or broadcast outings. Ian Murray’s Introduction to Gallus lists some of these sources:

Alex. Hamilton was born in Glasgow in 1949 and still lives there, as he has done for most of his life. He is known best for the stories in this collection, which have been published and broadcast both in Britain and the United States. His work has appeared in many journals and magazines, including the Times Educational Supplement, Akros, and Transatlantic Review, and in the book Three Glasgow Writers (Molendinar Press, 1976). Some of his stories have been broadcast on BBC television and radio and Radio Clyde. The author’s reputation as a reader of his own work makes him a frequent visitor to schools and colleges, where he was invited to give over 20 readings last year, and he has read from his more adult fiction at the Kelso and Frayed Edge Festivals, the Third Eye Centre, and the University of Glasgow.

Alex. Hamilton was awarded Scottish Arts Council writer’s bursaries in 1974 and 1979.

II

What went wrong - if indeed it is fair to call failing to get published necessarily wrong - after the initial interest in his work? Part of the answer, it may be argued, was Alex’s retreat, after Gallus, from writing in a fluent and readable and refreshing mixture of vernaculars, with some Scottish Standard English spliced in whenever he judged that a character’s speech-style demanded it. Alex himself did not regard it as a retreat, but rather as an advance, a striking-out into new literary territories, with new language uses to suit. If readers did not see fit to advance with him, he reckoned that that was their loss. In an email sent to me in 2016, he wrote this, referring to himself, oddly, in the third person:

He's long since given up writing for the (etymologically & demotically) ignorant. He - I - write(s) for a player-audience of two. If you exit before I do, there'll be a player-audience of one. If I exit before you: "CURTAIN!".

First of all, post-Gallus, Alex began to experiment with very short texts in a most elegant style of English, almost Augustan. One such piece, I recall, was called “Abdul, the Tobacco Curer”. He duplicated and spiral-bound a few copies for giving to friends, and for submitting (unsuccessfully) to publishers. Its content was slight, I have to say. Then he went on to elaborate that style in other texts, playing with words at every twist and turn, and wangling in allusions, drawn from various sources, print and otherwise. Thereafter, other languages besides English were plundered and bent to the same purposes, including French, Greek, Latin, Russian, and especially Scots. An interest in typographical high jinks followed, and photo-montage. Joyce’s portmanteau coinages and Mallarme’s calligrams were among his inspirations. As the form that he used became increasingly witty, and increasingly condensed, to the point of extreme brevity, his content became decreasingly significant, I thought. Often, the whole point of a text was a single pun, or a paradox.

When we discussed his writing over too much beer, or, in later years, over coffee or wine, and I questioned the form-over-content imbalance, Alex replied that he had no interest in putting across messages of any kind. He would leave such sententious and tendentious stuff to those authors with axes to grind. He held especial scorn, for example, for Susan Sontag and such engaged essays of hers as Regarding the Pain of Others.

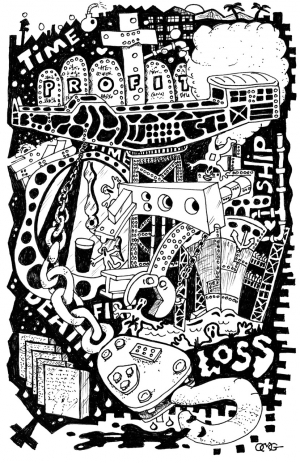

Once, he went so far as to say that he no longer held any belief in any grand narratives or big themes, his early commitment to Socialism and membership of the Labour Party having lapsed, as also his optimism regarding the possibility of any substantial social or political progress. Too many years working as a project manager on various EEC- and EU-sponsored public-private enterprises on brown-field sites - a job he entered after leaving the teaching profession - had tired him, and jaundiced him. He grew to distrust the political and business elites whom he was hired to serve, as also the popular and populist movements that gained support in the Nineties and Noughties across much of Europe.

Technological progress was a different matter: he embraced it happily, notably in connection with computing, hi-fi, and medicine; and for a while he engaged full-heartedly and doggedly in certain discrete issues that impinged on his life, as he listed in an email to me dated 2010:

Yup, sir: the enlightenment continueth. Wickedness encroacheth, or attempts to.

I've played my little part agin: the poll tax; the identity card scheme; the proposed closure of the FM network; & the environment on various fronts (& backs).

Persistence.

III

So that you can see and judge for yourselves, what I mean about Alex’s “retreat” - or his “advance” as he regarded it - let me juxtapose an early bit of text (published) against several later ones (unpublished):

From Our Merry (1976):

See, she had this wee kitten in her hands, and it was that toty you’d have thought it shouldn’t have been away from its mother....

“Heh, that sa a wee stoatir,” says Andy, and bends down to get a stroke at it.

“Lee it alane, you!” goes Merry, just as sudden as that, screaming and cuddling it real tight the way she does with her dolls. “Yir no tae touch it, awright? Awright? ... Kiz it’s mines!”

“Heh, wait a minnit, Merry,” I goes. “Whitdji mean, it’s yours? It’s probbli jiss ta stray ur that an that mean zit’s naebdi’s... relse if it sno a stray, it’s sumdi else’s.”

Compare the above with the following typical mini-text emailed to me in 2010. Note his copyrighting:

I think that I mentioned that I'm re-reading - and re-enjoying - Ellman's Joyce.

The attached occurred yestreen.

PRODDY GÆL SUN

Anglophile Ἴκαρος was a dead loss to his patter.

© DJANGO ROSS

Or this (2017):

As you know, I've been immersed in færie tales for the past couple of years, including Joseph's (translated) versions of a wheen of Celtic wans. Like you and Berger and the tellers of yore, my attitude is that a story's only a story, for if the hearers' interest wanes, you don't get your dram...

Currently reading thro - one per eve, of course - the latest (Penguin) translation of 1,001 Nights, which attempts to give all the stories, y compris the centuries' accretions. They haven't succeeded, but - kiz they hivnae nklewdit mines.

Which allows me to tell you of which, videlicet:

Sharazad's One Thousand and Second Tale

Woman, saith the Caliph. These three years, these thousand and one nights, thou hast succeeded in pleasing thy Lord. Thus, woman, I'm raisin thee to the status of my currant Sultana.

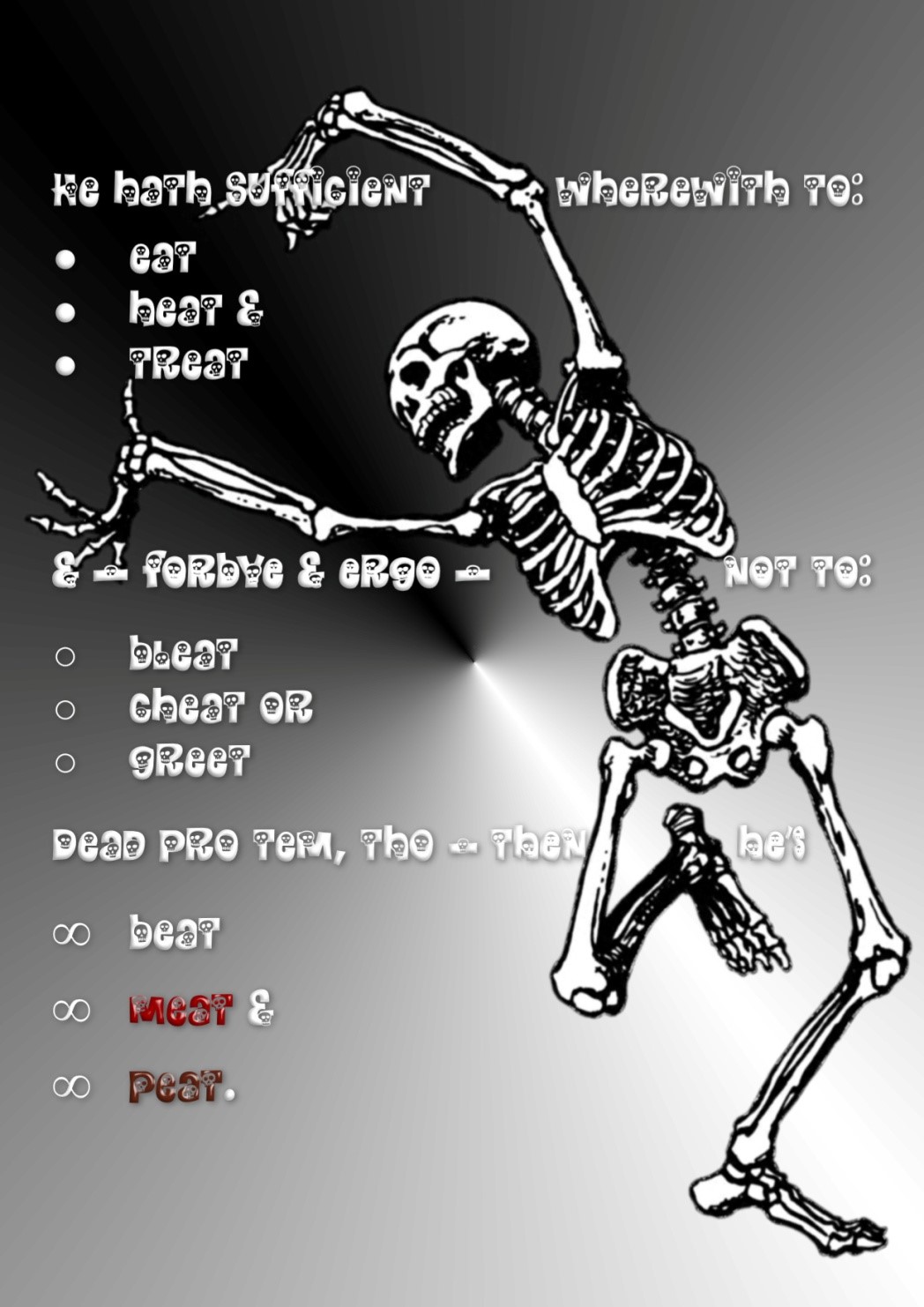

Or this, with graphics and a touch of colour, called The Retiree (2015):

IV

The last time I saw Alex was at a screening of The Sense of an Ending at the Glasgow Film Theatre. Afterwards, he praised the film, and said even better things about Julian Barnes’s novel, of the same title, on which the film is based. I was surprised to hear Alex speak well of these two contemporary works, as he usually saved his plaudits for the past, notably for works from the eighteenth century. He especially liked Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which he read and re-read several times over, in its complete six-volume edition; and, from the first half of the twentieth century, he especially liked James Joyce’s exuberant and encyclopedic two novels, Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, complemented or contradicted by Samuel Beckett’s increasingly condensed late plays and novellas. Julian Barnes and the film-makers did well, I thought, to break into this company of merit.

Looking back, from after Alex’s death, I begin to see the deep relevance that The Sense of an Ending had for my friend, especially when considered in light of the essay in literary criticism, by Frank Kermode, that lay behind the novel and the film, that Alex knew from his student days.

I have a hunch that Alex consciously shaped the way he lived and worked during the last decades of his life, with especial urgency in the last few years, by when I suspect he was beginning to have intimations of mortality. He shaped it so that the resulting narrative would made sense to him, even though the wider world’s narrative did not. In so doing, he was exercising the same set of skills that Kermode reckoned a novelist exercised in writing fiction, and we exercise in reading it.

Alex’s narrative prompted him systematically to edit loose ends from his life, cutting them out abruptly if that proved the neatest thing to do. Friends and family alike got this treatment. What is more, he increasingly ordered his life along almost monastic lines, governed by a sort of home-made liturgy of the hours. He set aside time each day for reading, and for writing; for listening to BBC Radio 3; for walking to the library to consult the only journal he had any regard for, The Economist; and for calling in at a shop where he could buy past-their-date foodstuffs cheaply, including not-quite-stale bread. Twice a week, he walked to a branch of Tesco about a mile from his house, sometimes on the way to a free concert or lecture in the University or Art Galleries; there he bought items that were discounted. Once, I recall, when I met him there by chance, he pounced on a tin of sardines, at 39p. “This is enough,” he told me, “for three meals, with a bit of bread.”

When at last his doctor told him how little time remained to him, without fuss Alex engaged the services of a lawyer, and gave his final instructions. (I know about this from a phone conversation I had with Alex’s former wife, after the event; she in turn had learned the details from the lawyer.)

Alex wanted to be interred with no ceremony in a plot in the same graveyard as his parents. He wanted the money that he had saved from his frugal living to be spent on two things: the printing of a collection of his writings, the details of which I have not yet been able to discover, and the performance of a cello concerto, in memory of his father, who had been a skilled worker in the shipyards, as well as a skilled amateur cellist. (This concerto he had already commissioned, from Edward McGuire.)

Eddie was one of the last people to see Alex. He visited him a couple of times at his flat. This is how he describes their meetings:

I had not been in touch with him for a few months and thought it was time to update him on progress in my composing the cello concerto that he had commissioned the year before. So, on October 4th 2018, I brought him a bound copy of the draft version of the piece, and pointed out where music had to be completed in each of the 3 movements. I was able to say the soloist - Robert Irvine - was hoping to premiere it in the Spring of 2019. It was not until about 2 hours into our conversation that he told me about his terminal cancer diagnosis. So I said I'd keep in regular touch. My next and final visit was nearly 3 weeks later on October 24th, again at his flat. He was much weaker then but was optimistic about attending the concerto premiere in the Spring. So I was surprised to learn that he had died a week or two after that - I had planned a third visit in November. I hadn't heard about him going into the hospice.

There was one matter that took Alex and Eddie a while to agree on: how to phrase the concerto’s dedication. Alex did not want his own name to appear on the score, only his father’s and the composer’s. After some discussion, they agreed to add the words “Commissioned anonymously”. My own suggestion to Eddie was that, when he publishes the work, he changes the dedication to, “Commissioned anonymously by his son”. Why edit oneself out, and become a ghost? That is one of the questions about Alex that I am puzzling over.

V

Alex’s burial did not go the way his sense of an ending had prescribed. To start with, there were more people at the graveside than he wanted, ten in all, if you count the undertakers and the gravediggers, plus a Golden Labrador called Hector, who seemed to enjoy the outing, to judge from a photograph taken by an old school-friend, who decided to invite himself along. The dog is straining at his lead, eager to be off sniffing. The photograph also shows another eager soul, quite unmourning because of her young age, namely Alex’s infant grand-daughter, whom he never knew he had. There were also more words spoken in that country churchyard than Alex had bargained for, not at the moment of interment, but immediately afterwards, when half an hour of animated conversation burst out. Some of it sprang from the mourners’ pent-up anger or sadness or bewilderment at the way Alex had lived his life, and treated them; some of it sprang from shared memories, or from shared curiosity about the others.

While there was no ceremony or service or religious observation, there was one little gesture of traditional leave-taking from one of the ten. The old school-friend took a handful of soil from the box offered by the undertakers. He went to the grave’s edge, and threw it on top of the coffin with its bright new brass name-plate. He didn’t want to not do anything after all the years he had known Alex - or Sandy, as he called him - and enjoyed his company.

Email attachment received from Alex in 2015

I have a sense of an ending of my own, different from Alex’s, and better than the one that actually happened. I have only belatedly arrived at it, some months after Alex’s grave was filled in, and the mourners went home, and the JCB mini-diggers that did the digging were taken to other jobs.

First, I would have been there at the graveside, along with many, many others - we should have invited ourselves. His old pals, James Kelman and Tom Leonard, would have been there, Tom Leonard restored to health, without any need of his walking-stick and a tube up his nose. Second, a cellist would have played the Sarabande from Bach’s Cello Suite Number 3, just as a colleague of my sister’s had done at her funeral some years earlier. Alex was there, and expressed great pleasure at hearing that noble music. Third, a jazz guitarist would have played another piece of music that Alex liked, Django Reinhardt's Nuages. When he was young, Alex played the guitar quite well, and till the end kept his instrument out of its case in his living room; but latterly he was unable even to hold it properly, let alone play it, as a disabling disease turned first one hand, then the other, into crab-like claws. Django famously lacked the use of two fingers, after being burned in a fire; Alex lacked the use of any. Fourth, every one of us there would have thrown our handful of earth into the grave, and either recited something or sung something, con brio. Fifth, we would all have gone to a pub somewhere afterwards, and held a riotous wake. Sixth, every one of us would have received a fat package through the post a few weeks later, from Alex’s lawyer. In it would have been a volume of Alex’s best writing, handsomely printed, and a CD of Eddie McGuire’s Cello Concerto. Seventh, we would have learned that we had been misinformed, and that Alex’s life never had taken a wrong turning.

This is me writing fiction, of a consoling kind.

VI

Looking back, summing up, it is clear that Alex was for a while a significant figure in an informal movement combining authors and publishers and broadcasters and readers and teachers, especially secondary school teachers such as Alex himself was at that time. Collectively, they shifted the centre of gravity of Scottish Literature further towards the vernacular, or vernaculars (plural) rather. Others continued that movement, with increasing success, while Alex chose to follow his other path, pursuing other projects. Tom Leonard and James Kelman, his former book-mates in the Molendinar Press volume, went on to become international faces and voices of the movement, each in his own distinctive way, and many others joined them, one of my favourites being Anne Donovan. Her story Hieroglyphics (2001) says a lot about vernacular and standard forms of a language, and says it in a vernacular so precise that it is an idiolect. Reading it sheds light on Alex’s early work.

The story describes a child’s struggles to decipher print, coming to Standard English texts from a Glasgow vernacular starting place. One word that gives her especial difficulty is her own forename: MARY. “That's ma name. Merry. But that wus spelt different fae merry christmas that you wrote in the cards you made oot a folded up bits a cardboard an yon glittery stuff that comes in thae wee tubes...” Here we find a lovely echo of lines written by Alex a generation earlier.

He similarly transliterated that girl’s forename as “Merry”, in his own story “Our Merry”, from Three Glasgow Writers. I remember querying Alex’s use of “Our” in his title, at the time we were getting Gallus ready for the press. I asked him if “Oor” was not the form he needed. Quickly and correctly, he pounced on my levelling, flattening, ignorant tin-ear. “It might be ‘Oor Wullie’,” he said, referring to D.C. Thompson’s cartoon character, “but in the North part of Glasgow, where my character comes from, and where I come from, it’s just as I wrote it: ‘Our Merry’.” There we see the same precision that made him place a dot after his own forename. “Alex. is an abbreviation,” he insisted. “It’s an abbreviation of Alexander, cutting the word short; hence the dot. So now yir tellt!”

VII

It would be a mistake for me to try to draw too large a conclusion about literary careers from considering Alex’s particular example. There is no compelling reason why writers should confine themselves to using vernaculars, there being plenty of good poems, short stories, novels, plays, etc. written in varieties of Standard English. There is no compelling reason, either, why they should desist from word-play and allusion and experimentation with layouts and fonts. If overly “realist” and “anti-formalist” assumptions were allowed to govern which works are deemed good, and therefore published, and which are deemed not good, and therefore not published, literature would be impoverished. Had such criteria been applied in the past, we would have lost access to a great deal of Hugh MacDiarmid’s polymath and polyglot output, to take one mighty example.

Other writers, too, would have remained in a limbo of unpublishability. Scotland’s first modern Makar, Edwin Morgan, would have suffered; or, at least, his concrete poetry inventions would have failed to make it into print. Similarly, some of Alastair Gray’s most typographically adventurous pages. And where would Hope Mirrlees’ s Paris be?

My comradely disagreement with Alex about the later direction of his writing did not relate to its form, considered on its own, nor to the demands it makes on us as readers to raise our game, but to its diminution of content. That is to say, my disagreement related to his conscious avoidance of engagement with the world, and the peoples in it, and their unavoidable concerns with big issues. In fact, I enjoyed Alex’s textual extravaganzas, as did a friend in London, the composer and poet David Johnson, to whom I showed some of Alex’s later work. “It is the sort of experimentation that excites by sound and rhythm more than sense,” he wrote, “as if he was writing in a language invented on the spot, or from a sort of speaking in tongues. Is it visionary? Mad? These questions alone spark an interest in me...” No, I just wanted Alex’s adventures in form to serve something bigger; and so, I suppose, did all those publishers who so often sent him rejection slips, or plain ignored his submissions.

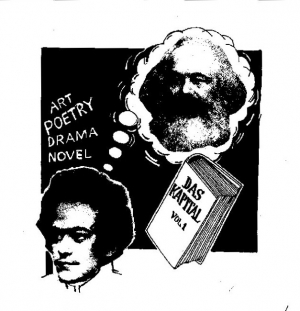

Ernst Fischer considered this diminution of content phenomenon, across all the arts in his far-ranging study, The Necessity of Art: A Marxist Approach. He saw it as a problem intrinsic to late capitalism, affecting creative individuals who were, or who became, detached from the realities of society, or indeed from their own true natures; in other words, as in Marx’s classic definition, individuals who were alienated. Fischer wrote:

The de-socialisation of art and literature produces the recurring motif of flight: the motif of deserting a society which is felt to be catastrophic.....

Alex’s flight became the dominating feature of his life and his work alike. How I wish he had chosen - had been willing and able to choose - to stay in touch with more things, more people, more issues, while still playing as he wished with form and language. How I wish he could have made Joan Miro’s manifesto-motto his own. In a 1948 interview, Miro, speaking of his own work, said, “Plant your feet firmly on the ground if you want to be able to jump up in the air.”

Suddenly, having pursued my argument thus far, I am aware of a certain rather large anomaly, namely a work-in-progress of Alex’s called The Reinhardt Variations, which I have only just remembered. It recounts the tale of a young technocrat’s journeys across several nations of Eastern Europe. Here, Alex avoided the form-over-content imbalance. He rendered chunks of real life, experienced at first hand, taken from a time and from places undergoing epochal change. Sure, the language may have been difficult in places, compressed, over-written perhaps, full of parodies of different kinds of writing, from newspaper journalism, to company report, to political polemic, to letter, to diary entry; but it was about something significant. Unfortunately, he never finished the novel, or even, latterly, spoke of it. It sank. I am left wondering if anything of it survives, maybe on a memory-stick or disk. I hope so, as it would show that Alex’s “retreat” (or “advance”) in his writing was not in a straight line, not 100 percent consistent.

VIII

There was a conference on brownfield site development in Moscow some years before Alex retired, that he attended. He was called to speak about his own work on such projects, being at the time employed by the European Commission in a variety of countries. He prefaced his remarks by quoting, in Russian, the opening sentence of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The same holds true, he told his fellow-attendees, even more so, of countries. As his life wore on, and the world’s politics got ever more dysfunctional, as it seemed to him, and as his own affairs went the same way, he became an expert in unhappiness; but it was his genius to carry on nonetheless, to hold fast, with a wry smile on his haggard face, and a bon mot forming in his mind, to be saved in his computer file.

Although, as I have shown, he favoured playfulness over seriousness in his writing, and in his public persona, I sensed a deep seriousness inside him, that darkened and hardened and shrank as the years went by, ending up as a nihilism similar to - and maybe even modelled on - Samuel Beckett’s, but without the Irishman’s great concern for the “still, sad music of humanity”, achieved through plain speech beautifully handled. A passage in Beckett’s Molloy expresses this nihilism perfectly. Alex read the novel both in its original French and in its later English translation, and sometimes quoted from it:

All I know is what the words know, and the dead things, and that makes a handsome little sum, with a beginning, a middle and an end as in the well-built phrase and the long sonata of the dead. And truly it little matters what I say, this or that or any other thing...

Clearly it did matter, however, at least some of the time. Alex’s dying instruction to his lawyer to arrange for a selection of his writings to be published was proof of that.

IX

There is much more that I could say about Alex’s life, and the way he chose to live it and to end it, yoking on as he did of a sort of Stoicism, if that is not too grand a term for his self-directedness, and his matter-of-fact acceptance of all the losses he suffered, and in some cases brought on himself; or should he be termed a Cynic, rather; or just a plain old misanthropic bastard? Maybe I have already said too much, divulging private matters about my friend. My intention is not to speak ill of him, but to recognise and try to understand his pursuance of his chosen craft, and to mourn the things that went wrong.

I am left with the questions I started with. The biggest one is this: how could a man who knew so much about other people’s lives choose so narrow and austere a narrative for himself? Here was a man who was deeply read in such deep studies of life as King Lear - to the extent that he sometimes adopted the mad king’s estranged and then reconciled daughter’s name, Cordelia, as a pen-name - and yet, looking back with selective fondness to his long-dead father, he chose to elevate his role as a son over all his other dealings with people, including his own daughters? And how could he lavish so much care on his complex weaving of witticisms and word-play - much ado about little - while neglecting so much else? It was as if, to reverse the idea contained in a line spoken by Cordelia in Shakespeare’s tragedy, Alex wanted his epitaph to be: “My tongue's more richer than my love.”

Ernst Fischer’s analysis of the de-socialisation of literature puts Alex in his historical context, but I am still left wondering why. Why, in this particular case, yet not in others, do we see a recurrence of Fischer’s motif of flight? To take two obvious counter-examples, Tom Leonard and James Kelman, both of whom came from similar class origins to Alex’s, and pursued similar destinations: they signally stayed grounded, never ballooning away into the least hint of alienation. Why the difference? Clearly, there is no simple iron law or hidden societal hand requiring de-socialising and flight. There must be other factors at work also.

Reading a life is the hardest thing.

X

While struggling to put this piece together, I found that a verse-elegy began to form in my mind. It went through about a dozen drafts, before the following text emerged. Alex would have thoroughly disapproved both of its form and of its content.

Dead Letters

by David Betteridge

Friend, I let you down;

and you let me go.

In doing so, you let me down;

and we let the silence that ensued

between us grow and grow.

We both were wrong,

needing as we did -

and still do - the other there,

in touch, if not in step or tune,

aware.

Disuse, the destroyer,

eroded friendship’s base;

and then, not telling anyone,

you went to a private place,

and straightway died;

you died with unanswered letters

left, and no good-byes.

I am not the only one estranged.

Year on year, you cut adrift

alike your family and your friends,

you hurting man.

Young, you kept your ear

close to the People’s complex voice;

you wrote their lives;

and your voice was heard.

Then, by cold degrees,

you privileged your own small take

and slant on things,

and your own sharp wit.

These led you to your solitude,

and turned the key on it.

Too soon you settled

into garret-ways, ensconced

in the clean order of your top-floor flat,

with the storm-doors shut.

Sitting there,

you pleasured in thesauruses,

and in the alphabet.

You had software that provided

every font of every type.

You wove them closely

into ever-dwindling texts,

with an ever-dwindling sense of right.

Your favourite letter

of the twenty-six was “O”.

You wrote the “O” that gives expression

to surprise; the “O” of salutation, too;

and the “O” of moans and groans,

extending once, in a tale of yours,

to twenty pages, then in colours

fifty more, some garish red, some blue.

You wrote the Venn diagram’s encircling “O”,

that separates one thing from the rest,

including (and excluding) self;

also the “O” that signifies an open wound,

or eye, or grave; and, finally, the “O”

that is the empty “O” of nothing, of which

no thing will come, as Lear observed;

and so it proved,

as your life’s course attests.

You found delight in Joyce,

striving to out-fun in print

that magic-making Irishman.

Now and then, in miniscule,

you ran him close,

but quite forgot to keep

your soul and heart engaged,

as he did his, and your feet

earth-pressed, like Antaeus.

Words, old friend, lost friend:

they were your true companions.

You kept faith with them,

cherishing them till death,

punning cleverly all the way

to the grave full-stop of your last breath.

Why did you not keep faith

with more?

Why did you turn

from the prime substantial world?

Why did you favour emptied signs

and metaphors?

Too late now to redraft

your life’s plot,

to redirect the great talent

that you had,

that it might serve a better end!

What’s done is done.

We must let it be.

Oh, that you’d kept in touch

with wider themes,

and with wiser friends than me!

Further reading: Caroline McAfee’s contribution, called “Glasgow”, which is part of Varieties of English Around the World, published by John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 1983, available online. It contains extracts from Alex’s short stories, and from an early novel, Stretch Marks.