Poverty at the Movies

Being able to afford something, or for a child not being able to have something, is where the narrative of poverty begins. However, it has been obscured by the liberal idea of progress – the idea that some people are more advanced than others because that's how nature has played out. This discourse continues to how we assess poverty and judge the poor.For many, poor equals brown or black people from Oxfam adverts; many people over the world live on less than two dollars a day:

So what do we mean when we talk about poor people with no money in richer Western countries? For many 'poor' in the West means that they have ended up there for a few reasons. It could be that they have not worked hard enough, aren't talented, or in the less reactionary of opinions, it comes down to bad luck. Falling on hard times as they say. A truly personalised and unique case often for everyone. It's framed as a moral failure of the person or those around them rather than a societal issue.

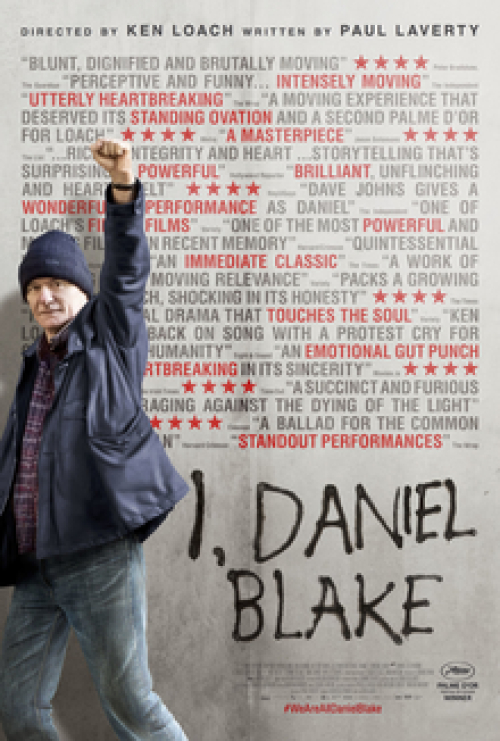

I, Daniel Blake is a social realist film by Ken Loach that shows the realities of the situation for benefits claimants in the UK but often leaves people questioning if it has been laid on too thick. Does that mean the problems don't exist though? As you watch a close-to-retirement Daniel jump through the faceless hoops of the state you gain a sense of sadness for the person stuck in the system, a sense of indignation. It's not his fault he has an illness which means he gets lost, coming up against faceless apparatchiks to get his 90 quid to last him two weeks.

Yet for every social realist film that attempts to combat this matter we have serial blockbusters like Star Wars. In episode seven, The Force Awakens, we see Rey scavenging for food on a sandy Jakku. She is on a dead-end planet and is poor in many ways. For Rey to end up here it was a moral decision made by her parents to abandon her. She had been placed there for reasons out of her control. We see her making her way off the planet because she has a bigger mission beyond her own story, but what if there was no bigger story? What if Rey just got bored of being a scavenger? I mean we see her stuck inside a system, selling what she finds to get inflatable bread and green biscuits. She even tried to stay out of obligation.

Star Wars is representative of a widely held liberal view that poverty – and living in that state – has a moral kernel as opposed to a systematic one. As if we are all like Rey, free to choose when to leave but first we have to find our bigger calling, work hard and try harder. A more obvious version is The Wolf of Wall Street where we see Leonard de Caprio's character force his way to the top of the American food chain with wit, balls and talent. Success is yours, if you want it.

Maid on Netflix is an interesting synthesis of the two. A woman decides to leave her home with her child because of domestic abuse. This is not a clear-cut decision for everyone but does highlight issues around various forms of abuse in relationships. She goes from being poor to being poorer, and is thrown into a world of food stamps and government aid programs. She has to get a job as a maid to claim any help.

The way we see Margaret Qualley portray the effects of poverty on her mental health is refreshing, as a lack of money can make you so stressed and have the same brain capacity as somebody who is intoxicated with alcohol. Furthermore, the portrayal of the distance that is created between you and your close ones when you suffer from depression is also noteworthy. But the series also highlights practical issues around documentation, rights, money and precarious work, all of which the poor person has to negotiate on top of the stress of having no money and to provide for a child in a hostile and cold environment – this is on a material and spiritual level.

I'm not sure how superior a member of the royal family would feel in these circumstances. The series shows the world is not made for the poor. The poor have to navigate around the world. This isn’t easy when you have an unstable home life, no money and no self-esteem to match. I found myself rewatching this series again, 3 years after it was initially released. Thinking about how I felt the first time and comparing it to now, I feel that the world is even more hostile to anyone who is not ‘making it’ or ‘hustling’ to make ends meet. The entrepreneurship culture has darkened the internet and in turn our workplaces and classrooms.

The series works well highlighting various issues related to abusive relationships, in-work poverty, mental health both as a person and carer, and alcoholism. One of the major contradictions is that it was written by someone who has made it on her own talent. This isn't a bad thing, and this is something to be praised as the writing is phenomenal, but it also could be used to support the idea that if you work for it you can achieve it. Sadly, not everybody will write a Netflix series.

Relative poverty or in-work poverty is not because of a lack of will or a moral failing. If anything, it is a moral failing on a society level as we continue to use a broken (for the poor) capitalist economic system that forces people to stay in abusive relationships and gives them little help to alleviate the stresses of living in poverty. Pull yourself up by the bootstraps they say, but what if you need to buy new laces?

Alan McGuire

Alan McGuire is a former mental health nurse from Swindon. He currently lives in Madrid teaching English.