The barriers to working-class writers: Review of The 32: An Anthology of Irish Working-Class Voices

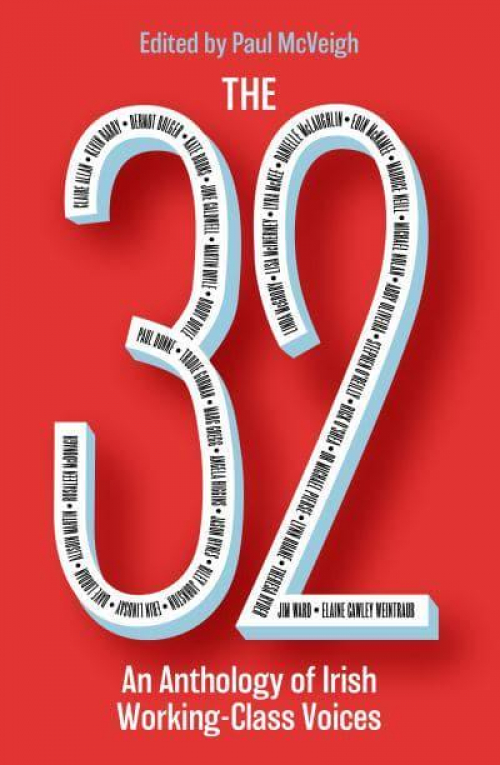

Jenny Farrell reviews The 32: An Anthology of Irish Working-Class Voices, edited by Paul McVeigh

Working-class writing is coming to the fore in Ireland. “The 32” follows the publications of two anthologies of working people’s writing, “The Children of the Nation” and “From the Plough to the Stars” (Culture Matters, 2019, 2020).

All three anthologies stand out in the literary landscape for being just that: anthologies. Much as the publications of individual working-class writers must be admired for breaking through the class barriers in the publishing industry, these anthologies together give a strong sense of the voice of a class speaking; the strength that arises from standing together, a fact to which The Irish Times and the Independent, in their reviews, are oblivious.

One of the statements this book makes, and some of its contributors attempt to answer, is how to define the working class. The texts printed within its covers agree on some of the basic aspects: above all, it means to be poor. It certainly means to be scorned by those who represent the establishment and dominate education, culture, politics, the media. They reinforce their preconceived, ill-informed notions of the working class by all means at their disposal. Erin Lindsay observes: “Whether it’s in film, music, or conversations overheard on the street, the idea of being working-class is contorted and presented back to us without our presence in its creation.” This motivates taking charge of one’s own narrative, a theme that recurs throughout the collection.

This is an issue of key relevance to publications such as The 32 and the Culture Matters anthologies. These anthologies undertake the epic task of removing class barriers and creating a more democratic and grassroots publishing culture, indeed focusing on the class that is generally excluded.

Censorship by RTE

By way of example, Alan O’Brien, working-class writer and contributor to the Culture Matters anthologies, submitted his radio play “Snow Falls and So Do We” to RTE, based on the true event of a woman dying of hypothermia in a Ballymun flat. O’Brien won the P.J. O’Connor Award for Best New Radio Drama but encountered significant opposition from RTE when they were to broadcast his play. O’Brien was told his lines were crude and that the portrayal of the Gardaí was unacceptable. A significant and inappropriate change in the narrative was suggested whereby Joanne, rather than disliking the Garda known as "miniature hero", actually fancies him, and wants him to take her out of this hellhole.

This smacked more of make-believe Hollywood that the reality of Ballymun. O’Brien’s statement that the people of Ballymun have a very different experience of the Irish Constabulary was sneered at. He rejected the changes to his script, explaining his reasons. But RTE made them anyway and many more, without further consultation. Most significantly, they changed the ending of a working-class woman dying as a result of social depravation, metaphorically (and actually) freezing to death. Working-class tragedies are not allowed. The establishment will only accept its own interpretation, and rewrite history accordingly.

So, not only are working-class people excluded from mainstream cultural consumption, they are also prevented by the media – including the publishing industry – from expressing artistically their experience of the world. By recognising this class barrier and attempting to tackle it, these anthologies of working-class writing are blazing a new trail. However, unless other cultural workers, institutions, trade unions and universities acknowledge this deficit with a view to redressing it, they will remain a drop in the ocean.

Kevin Barry writing in “The Gaatch” points to where establishment prejudice invariably leads:

On Thursday mornings I attended the sittings of Limerick District Court. I did the courts for a couple of years, and I can’t remember ever hearing a working-class defendant’s word taken over the word of a guard. You could predict with high accuracy the forthcoming judgements from the look of the defendant taking to the witness stand. If he or she had a working-class kind of gaatch to them – as we’d say in Limerick, meaning that they carried themselves in a certain way, dressed in a certain way, spoke in a certain way – they would very likely be found guilty.

Being presumed guilty because of belonging to the dispossessed, is reiterated in Rosaleen McDonagh’s experience as one of the Travelling community:

Five o’ clock in the morning the sound of police sirens. Bursting into the caravan, looking for stolen goods, tax and insurance, drugs, firearms. They pull my brothers and my father out of bed. Trousers and boots, no shirt. Made to stand in the middle of the site alongside thirty or forty other men and boys of various ages. … Nothing was found; all tax and insurance related to our vehicles were in date.

And so, the importance of speech, dress, address, and school, appear time and again in these texts. The greatest part of these are memoirs, or ‘faction’. Poverty looms large, and a sense of deliberate exclusion from mainstream lifestyle pervades. Class barriers are seen and cited all the way, and education is viewed as a way out. Many of the authors describe the difficulty of pursuing a writing career.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that an overall impression forms that in order to live a better life, you need to get out of the working-class trap. The disadvantages seem to outweigh any positives. And yet, Erin Lindsay states in complete contradiction to the received mainstream view:

Growing up, my house was full of conversations and debates about history, philosophy, politics, life, ethics, love – they taught me everything I know.

And Dermot Bolger says – with Gorky – that working life is a university:

It was a last valuable lesson I learned in the only university I ever attended before commencing my journey as a writer.

Class consciousness, pride and solidarity

Working-class writing is as old as the working class itself, arising with the Industrial Revolution, landless peasants before that, much of this in the oral tradition. Within class society, the working class is to a large extent indeed cheated out of fair pay, cheated out of education and opportunities. The introduction to “From the Plough to the Stars” presents a Marxist definition:

Our understanding of ‘working class’ are those people who sell their labour power and share only marginally in the fruits of their labour. They create the basis of national wealth, yet their living conditions are frequently precarious. This includes the urban and rural proletariat, small farmers as a peripheral group, as well as the rising number of people in precarious employment, the homeless and the unemployed.

In some of the texts in “The 32”, you find a sense of solidarity and pride in class, the sense that surely poverty and lack of education is not the ultimate and eternal definition of working class – that there is a potential that will allow this class to challenge the society that keeps it on the poverty line. This strength, this process of liberation, is a hallmark of Maxim Gorky’s working-class writing. It envisages a society where there is little difference in income and living standard between the skilled industrial workers, farmers and professionals. In this (socialist) society being working-class does not spell poverty, poor education and neglect by society. It is entirely possible to be a working-class intellectual, and it was in the USSR and other socialist countries that working-class history and art first became the subject of academic research. It is thus ignorant and damaging to be told that having achieved a university education, or working in the arts, means one is no longer working-class.

The texts in this book focus on the here and now in Ireland, the lived experience of the authors, ranging from the 1950s through to 2020. Paul McVeigh, has achieved a good balance of contributions from the Republic of Ireland as well as the North. Here, the sectarian prejudice against the Catholic population adds significantly to social inequality, as several contributors attest. And when we refer to bigotry and discrimination it is to welcomed that a member of the travelling community, Rosaleen McDonagh, as well as a representative of the queer community, Marc Gregg, are given the opportunity to add their voices.

Regrettably, no Irish language texts are included. This would have paid necessary tribute to the long tradition of working-class writing as Gaeilge in Ireland. The exclusion of this tradition by the publishing industry is shameful and needs to be challenged by those who have taken up the pen to put an end to social injustice. This can only be achieved by the whole of the working class standing together.

Along with “The Children of the Nation” and “From the Plough to the Stars”, “The 32” presents a differentiated image of what it means to be working-class in Ireland today. These three anthologies will be followed by a fourth publication, “Land of the Ever Young”, a beautifully illustrated book of working people’s writing for children, in November of this year.

Jenny Farrell

Jenny Farrell is a lecturer, writer and an Associate Editor of Culture Matters.

Latest from Jenny Farrell

- Poetry for the Many, an anthology by Jeremy Corbyn and Len McCluskey

- A hopeful vision of human renewal: the theatre of Seán O'Casey

- Art that's rooted in the upheavals of his time: Caspar David Friedrich, 1774-1840

- A Drive to Change the World: James Baldwin, Black Author, Socialist and Activist

- A woman's perspective on the invisible front: A review of 'The Shadow in the Shadow'