The strength, courage and creativity of women: the paintings of Artemisia Gentileschi

Jenny Farrell writes about Artemisia Gentileschi (8 July 1593-1656)

One of the great weaknesses of bourgeois establishment art analysis is that the artist and their work are usually seen in isolation, like an accident that occurred for no apparent reason. As though Shakespeare or Beethoven could have created the same works in the third century BCE, for example. An understanding that a particular artist lived in a specific time in history, that needed just this voice, is absent in most cases. Such lack of historical understanding suggests that people live outside history, that they were always the same, and robs art of its revolutionary potential as well as its power to help us understand history as change.

It is for this reason that in presenting the outstanding 17th century realist artist Artemisia Gentileschi on her 430th birthday, it is useful to provide some background to the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation and the Baroque period.

The bourgeoisie and religious emancipation

The emergence of the bourgeoisie between the 13th and 16th centuries from traders, merchants, and artisans, marked the beginning of the modern, capitalist era, starting in Italy. This new social class, seeking political power to underpin and expand its growing economic might, found expression in the Renaissance, which showcased its confidence and philosophic, artistic as well as scientific achievements.

With the advances in science and navigation, sails were set, new countries and continents discovered, their people colonised and enslaved. Gripped by a fever for gold and silver, and finding highly profitable luxury items such as tea, sugar, cocoa and tobacco, indigenous resources and populations were exploited and markets expanded. All these stolen goods helped create the wealth of the European bourgeoisie.

The rising bourgeoisie’s need to legitimise their political aspirations at all levels was reflected in the attack on the supremely hierarchical feudal Church, and its replacement with a more egalitarian Protestant structure that aimed to eliminate intermediaries. This new ideology aspired, in theory, to political power for all.

The Reformation, originating in Germany in 1517, represented religious emancipation from strict feudal hierarchies. The German peasantry took the Reformation to its ultimate secular conclusion and bravely undertook the great peasant war that Engels termed an early attempt at bourgeois revolution, ultimately defeated by the aristocracy in liaison with the Church and the emerging new monied class. The Diggers inherited this legacy when the time came for their participation in the English Revolution.

The Reformation weakened Catholicism across Europe. With the exception of Britain, there were no successful bourgeois revolutions that abolished feudalism and consolidated the growing economic influence of the middle class at that time. Instead, feudal absolutism emerged, with the nobility retaining their position as the ruling class, albeit with increasing capitalist influences shaping the economy.

During the period from 1555 to 1648, the Counter-Reformation took place, characterised by Catholicism’s political and military actions to thwart the effects of the Reformation not only in central Europe. The Counter-Reformation resulted in the resurgence of Catholicism, significant shifts in political power in Europe, and the restoration of Austria, Bohemia, and Poland to Catholicism. Catholic powers such as Spain and Portugal played a dominant role in establishing colonies in the Americas, imposing Catholicism on the indigenous populations. The Jesuits played a prominent role in this movement. If the Renaissance was a turbulent time, the Counter-Reformation was even more tempestuous.

Visual art and social class

In Europe, the Baroque style of art developed in tandem with the Counter-Reformation. The arts of the Baroque era reflected the spirit of this period, aiming to glorify the absolute power and outward splendour of the ruling class. The elite deluded themselves into believing they possessed total power, although this had diminished. However, this era also witnessed an unprecedented differentiation of art across social classes: alongside the cultural expressions of the nobility, bourgeois-democratic and upper middle class art forms emerged.

Among the most famous patrons of the arts at the time were the Spanish Borgias of aristocratic stock and the Italian Medici whose wealth came from banking originally and who later merged with the aristocracy. The Baroque style represented the interests of the upper middle class aligned with the nobility, while realist artworks reflected democratic tendencies. Caravaggio was a giant among these and had a great influence not only on Italian art, but soon on art across Europe. To follow the Caravaggesque, realist style was deemed subversive and touched the nerve of the time.

Among these followers was Artemesia’s father Orazio Gentileschi (1563-1639), a highly regarded painter in his own right. He was acquainted with significant intellectual figures and scientists of his time, a time when scientific and artistic spheres were not mutually exclusive. He moved in circles which founded the Accademia den Lincei (founded 1603) with Galileo at its centre. This must be seen in the context of an ongoing witch-hunt against scientist such as Giordano Bruno, whose ideas contradicted the prevailing religious doctrines of the Catholic Church. These included Bruno’s understanding that the Earth orbited the sun, an observation shared by Galileo.

The Roman Inquisition found Bruno guilty of heresy, emphasizing its determination to suppress dissenting ideas and enforce its authority. Bruno refused to recant his beliefs and was burnt alive at the stake. The execution of Giordano Bruno by the Roman Inquisition in 1600 intensified the climate of caution and fear among scholars and scientists and had a significant impact on Galileo.

Despite this, Galileo continued his scientific observations and research, and developed his own evidence in support of the heliocentric model. He published his findings in 1610, challenging the prevailing geocentric model supported by the Catholic Church. In 1616, he was summoned by the Inquisition and ordered not to teach or defend heliocentrism. The publication of Galileo’s most famous work, “Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,” in 1632, presenting his arguments for heliocentrism, led to Galileo’s trial by the Inquisition in 1633. Found guilty of heresy, he was forced to recant his views and sentenced to house arrest until his death in 1642.

In art, the towering figure of Caravaggio had blazed the trail of realism. He painted from live models even for religious and history themed works, challenging authority on every level. His realism, transporting a scientific and democratic element into the art of the time, greatly influenced Gentileschi and other painters. As one of the proponents of the Caravaggesque style, Orazio was sought after in Genoa, Paris, and eventually London. Genoa (a republic since 1528) attracted many artists; it was a leading European banking and commercial centre.

Orazio left for Paris to work for Marie de’ Medici and his Caravaggesque realism was sought after by painters there. Two years later, he moved to London probably due to the marriage of Marie de’ Medici’s daughter to Charles I. During his twelve years in London (1626-39) in the wider circle of Charles I’s court, Orazio lost this realism and his paintings began to suit ideals of courtly beauty. His figures now had porcelain skins, wore rich draperies, and lacked psychological depth.

Artemisia Gentileschi

Of Orazio’s four children, the eldest was his only daughter, Artemisia (8 July 1593-1653). Their mother Prudenzia died in childbirth when Artemisia was twelve. Orazio trained all four children in his workshop, but Artemisia was the one about whom he wrote, she had “in three years become so skilled that I can venture to say that today she has no peer; indeed she has produced works which demonstrate a level of understanding that perhaps even the principal masters of the profession have not attained.”

Aged seventeen, Artemisia was raped by Tassi, a painter colleague of her father’s. At the trial, instigated by her father, some months later, Artemisia (a painter!) was tortured by means of a sibille (torture instrument made of metal and rope, that tightened round the base of her fingers) in order to establish whether she was telling the truth. The records of this trial document her experience in her own words. At that time, Artemisia ascertained that she could not write and barely read. Her experience is reflected in her work in many ways – in her strong and realistic female characters and the specifically feminine viewpoint that she brings to familiar topics on her canvases. And of course, she also knew the female nude anatomy better than her male colleagues. Artemisia too stood firmly in the realistic tradition of Caravaggio.

Immediately after the trial, Artemisia was married to the brother of the man who had provided legal aid to her father during the trial, and moved from Rome to Florence. Here, Artemisia spent eight years. She learned to read and write, and she was friendly with Galileo. She also became the first woman member of the official art establishment, the Accademia del Disegno. However, Florence was not open to Caravaggesque realism. Artemisia returned to Rome for six years, before moving on from there to Venice (1627) for at least two years and finally, following another sojourn in Rome, settling in Naples (1630), the second largest metropolis in Europe at the time.

Artemesia’s first masterpiece was Susanna and the Elders (1610, Schloss Weißenstein, Pommersfelden, Germany), was painted in Rome when she was only seventeen, and which preceded her rape.

The story of Susanna, from the Book of Daniel, tells the story of the young wife Susanna in Babylon. While bathing in her garden, two prominent elders of the community secretly watched Susanna and conspired to blackmail her, threatening to accuse her of adultery unless she yielded to them. When Susanna refused, they claimed to have witnessed Susanna committing adultery, swearing this under oath. However, Daniel, known for his wisdom, exposed their conflicting testimonies. The people turned against the elders, who were then sentenced to death by stoning.

Artemisia’s Susanna and the Elders is a powerful, dramatic depiction of the biblical story. The painting presents the viewer with a close-up composition, focusing on the figure of Susanna. She is seated on a stone bench, vulnerable, all but nude. Her whiteness, her innocence, is emphasised and contrasts sharply with the fully clothed, leering men, who have crept up behind her. Susanna’s upper body is twisted away from them in shock, her fearful face turned as far away from them as possible. Her distress is accentuated by the desperate yearning of her hands to push the men away, as their hands perilously encroach upon her.

While Susanna is alone, the men form a treacherous unit, one man’s arm around the other, whispering, the second man holding his index finger vertically to his lips to seal the pact of silence. Artemisia uses chiaroscuro to deepen the dramatic effect of her narrative. Natural light shines on Susanna’s torso and the sheet, which are the men’s central interest. This colouring, along with the massive weight pushing down from the sinister predators, intensifies the emotional atmosphere and highlights Susanna’s isolation and vulnerability.

Another popular Biblical subject Artemisia turned to was that of Judith slaying Holofernes, a theme also tackled by Caravaggio and Orazio, two painters in Artemisia’s immediate circle.

The story of Judith slaying Holofernes is found in the Book of Judith and is set during the siege of Bethulia by the Assyrians, under the command of the general Holofernes. The wise widow Judith devises a plan to save her city. Dressed in her finest garments and accompanied by her maid, she goes to the camp of Holofernes under a false guise. Holofernes invites her to a banquet in his tent. When Holofernes becomes drunk and falls into a deep sleep, Judith decapitates Holofernes with his own sword. Judith and her maid flee from the camp, taking the severed head of Holofernes with them. When they return to Bethulia, the inhabitants are filled with renewed hope. The Assyrians retreat, and the Israelites are delivered from their enemies.

Artemisia painted Judith and her maidservant several time in her career, twice Judith Slaying Holofernes (1612/13 and ca. 1620, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Itlay). We will look at the second painting here, painted in Florence, as it has gained in realism compared to the first. However, the basic composition remains the same. While Caravaggio in his painting of the scene had already brought the maid into the room with Judith and made her complicit in the beheading (in the Bible, she waits outside the bedroom), Artemisia assigns both women an active role: the maid holds down the powerful man while Judith performs the actual killing. Both women are needed to accomplish this, one cannot do without the other.

Unlike Caravaggio’s depiction of a very elderly maid observing the action, Artemisia presents a young woman, whose full bodily weight and strength is required to pin down Holofernes. Again, compared to Caravaggio, Judith herself is also a more convincing executor, an incredible force emanates from her. The power, energy and sheer strength of these two women in action is almost peerless in the history of art. They have come to do a job, we witness them doing it, at the height of the action. Their fully extended arms push down on the general with great force.

Compared even to her own earlier painting of the same scene, Artemisia’s detail has become more realistic. True to the Bible, Judith is dressed in her finest clothes (she needed to impress Holofernes), down to the bracelet, which according so some experts depicts Artemis, the goddess of the hunt and chastity. A close look at the bracelet reveals a figure dressed in a hunting costume, with a bow and quiver of arrows.

The women are splattered with blood (a realism absent in Caravaggio’s interpretation and Artemisia’s first version of the scene), Holofernes’ blood spurts from his neck onto the bed and the women. Their faces capture the intensity of the moment. The composition, with the sword at its centre, creates a sense of immediacy and emphasizes Judith’s determination. The figures are dramatically illuminated, heightening the tension and drama of the scene and deepening its emotional impact.

The final picture I would like to look at is Artemisia’s self-portrait as The Allegory of Painting (La Pittura, 1638-1639, Royal Collection, England), painted in London while she stayed with her father for a few years, when she was in her mid-forties.

The Allegory of Painting was a common subject particularly in Renaissance and Baroque art, with Painting personified as a woman. In her depiction, Artemisia follows the description by her contemporary Cesare Ripa in his book on art iconography. However, unlike her male colleagues, she could depict herself as the Allegory. And so this picture The Allegory of Painting (La Pittura) is both allegory and self-portrait. Unusually for a self-portrait, this artist does not look at the viewer. She is completely focused on her creative activity.

The artist is also shown from a most unusual perspective – one that required two angled mirrors to allow observation of this posture. The painter is positioned to the side of the canvas, with a diagonal running top left to bottom right of the picture along her painting right arm and her chest. This off-centred positioning creates a singularly dynamic and unconventional composition. The sleeve on the right arm is rolled up, she is wearing a brown apron over her dress – she is working. In her right hand she holds the brush that is about to touch the canvas.

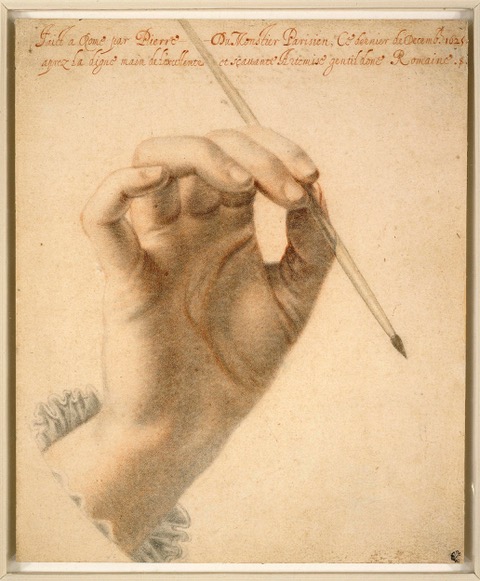

Over a decade before, on New Year’s Eve of 1625, the French artist Pierre Dumonstier had drawn The Right Hand of Artemisia Gentileschi Holding a Brush (British Museum, London, England) in Rome. It is interesting to compare them.

In her left hand, the artist subject holds the rectangular palette, resting on a simple support. In keeping with the intense concentration on her work, the painting is bare of any detail. Artemisia is both the subject and the object of the picture. In so deliberately sparse a picture, every little detail counts. Here, gravity causes a pendant to hang away from the angled body, thereby attracting attention. The pendant represents a mask, as required in Ripa’s description of the Allegory. It signifies that what we are shown in art is only the image of something, not the actual thing. We see the image of Artemisia, not Artemisia. Rene Magritte in 1964 would say about his picture of an apple: This is Not an Apple. Ripa had stipulated in his description that it should read on the mask: “imitation”. Artemisia sees no need to say this; she believes in the viewers’ intelligence to work this one out for themselves.

The entire focus is on the person of Artemisia. In the background there is a vertical line, separating two brown tones. The lighter shade probably signifies the grounding of the canvas before the imminent application of other paints by the artist. As we witness the artist touching the canvas, we behold the moment of creation. Both canvas and wall are bare, suggesting that the painting is not finished, but in the process of creation. This is the allegory of painting at work. It is an amazing work of art.

As one of the great disciples of Caravaggio, although well-known, Artemisia received no public commissions while resident in Rome, Florence or Venice, as her realism must have been seen in conflict the Baroque ideals. Naples was more open to it, and it was here that she spent the last twenty years of her life and died, possibly during the plague of 1656. All but forgotten for centuries, her realist art was rediscovered and celebrated in the twentieth century.

As one of the great disciples of Caravaggio, although well-known, Artemisia received no public commissions while resident in Rome, Florence or Venice, as her realism was seen to conflict with Baroque ideals. Naples was more open to it, and it was here that she spent the last twenty years of her life and died, possibly during the plague of 1656. All but forgotten for centuries, her realist art was rediscovered and celebrated in the twentieth century. She transports the women of her time into ours like no other artist, and her convincing depiction of their strength, courage and creativity in the early days of the capitalist era, confirms her viewers' conviction that change can be wrought.

Jenny Farrell

Jenny Farrell is a lecturer, writer and an Associate Editor of Culture Matters.

Latest from Jenny Farrell

- Poetry for the Many, an anthology by Jeremy Corbyn and Len McCluskey

- A hopeful vision of human renewal: the theatre of Seán O'Casey

- Art that's rooted in the upheavals of his time: Caspar David Friedrich, 1774-1840

- A Drive to Change the World: James Baldwin, Black Author, Socialist and Activist

- A woman's perspective on the invisible front: A review of 'The Shadow in the Shadow'