A Driven Man: Review of ‘Kubrick and Control: Authority, Order and Independence in the Films and Working Life of Stanley Kubrick’ by Jeremy Carr

Like many eager teenagers who found themselves sleepless and cinephilic during the Gilded Age of VHS in the 1980s, you genuinely felt the presence of the director of The Shining at your shoulder as you sat alone in the living room and watched his vision of the unfamiliar, the unnerving and the uncanny ominously unfold.

The absolute exactness of everything on screen, in concert with the hypnotic electronic orchestration by Wendy Carlos, drenched with such doom and dread, overwhelmed and compelled you to return to its psychopathy again and again until, without knowing it, you had soon learned the dialogue verbatim as if it was a lyric from some obscure prog-rock album entitled ‘Grand Guignol’.

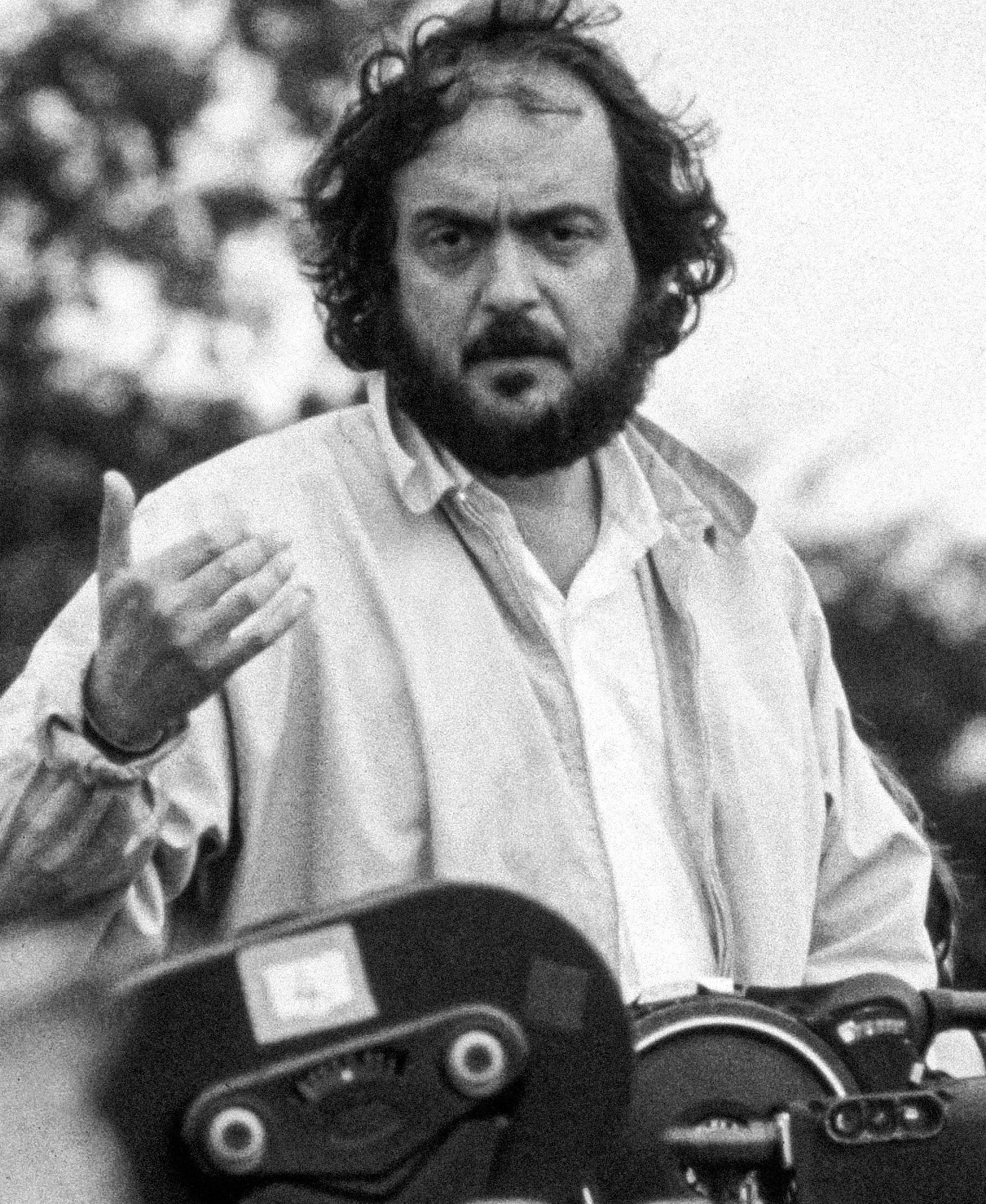

Jeremy Carr’s comprehensive hagiography of Stanley Kubrick’s career of creative compulsions and authorial control conjures up many, many youthful memories such as this and, as a consequence, it is a must-read for anyone who pines for the serious aesthetics of mainstream cinema to return.

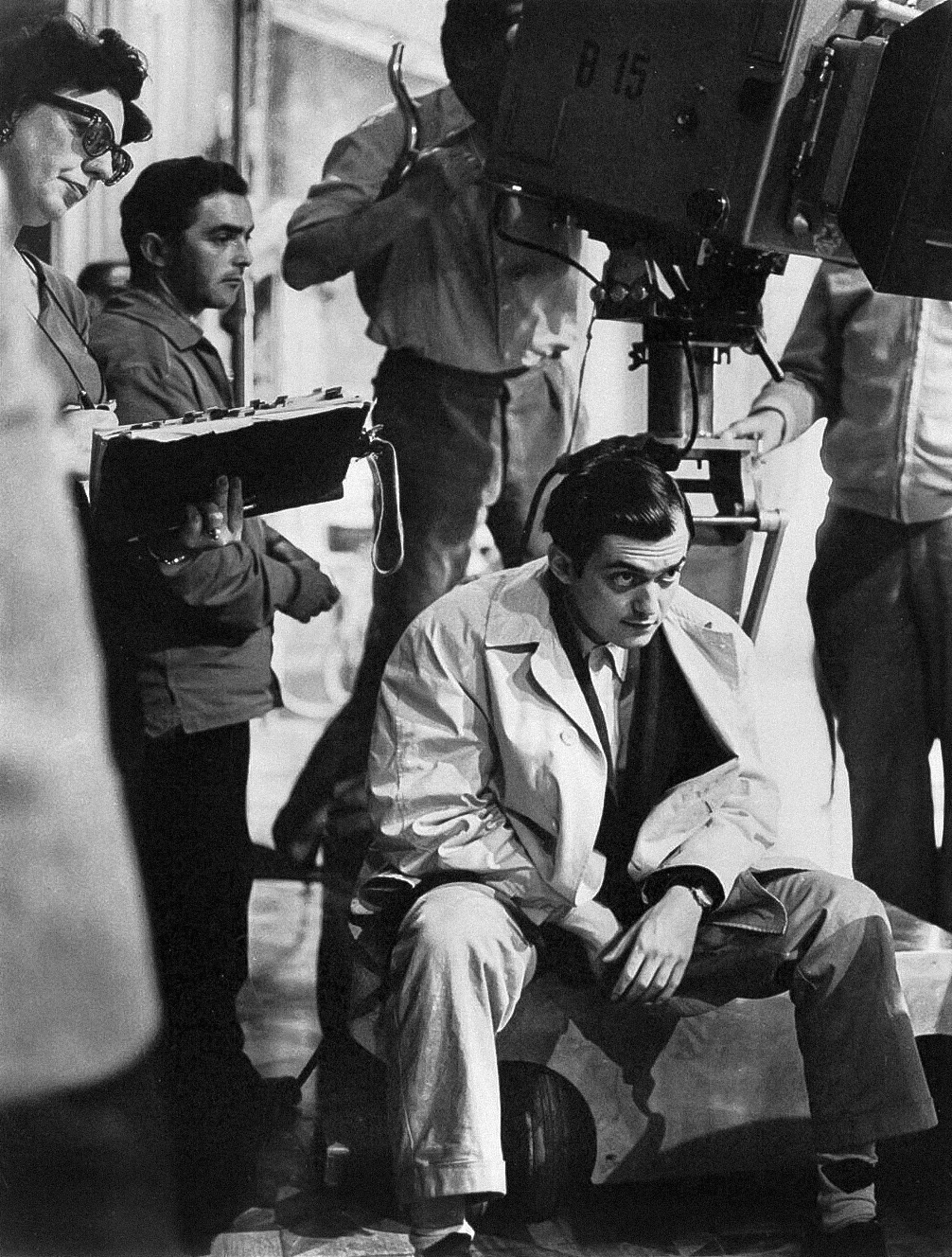

Kubrick first began to learn to ‘direct his subjects, to control light and shade, to understand lenses, composition, exposure, and balance within the frame’ as a precocious 17-year-old staff photographer working for Look magazine in New York between 1946 and 1950. According to Dr James Fenwick:

[he] seems to have wanted to push the limits of the creative freedom he was offered at the magazine … [attempting] to broaden his autonomy … [and] invest his own personality into his work.

Onwards and this competitive attitude and approach to producing cinema with distinct authority was helped and honed throughout the 1950s by way of the chess matches he played against the regulars in Washington Square in the shade or under street lamps; a meticulous métier which he would introduce to the cast and crew on the movie sets he was later to govern. As the director himself explains in John Baxter’s Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (1998), if chess had any relationship to filmmaking ‘it would be in the way it helps you develop patience and discipline in choosing between alternatives at a time when an impulsive decision seems very attractive.’

Day of the Fight became Kubrick’s first motion picture at the age of 23, a 16 minute black-and-white documentary which follows Irish-American middleweight boxer, Walter Cartier, as he prepares to fight Bobby James on April 17, 1950. Here, in between the staging and the spit, the uppercuts and the close-ups, Carr identifies the shadow of a leitmotif which would eventually loom over the director’s entire oeuvre: the driven man.

In The Killing in 1956, for instance, his first proper studio picture for United Artists, veteran ex-con, Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden), strides across the screen as he confidently describes to his fiancée the herd of hoodlums he is about to corral with the sole purpose of pulling off a daring $2 million robbery at the racetrack.

In turn, in 1957 Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) can be seen in Paths of Glory to be a character cut from the same thick cloth, single-minded in his lofty and loquacious attempts to hold the French military command to account as he defends three soldiers who have been arbitrarily accused of cowardice during World War I.

Crucially, this incipient interpretation of the masculine desire to confront, combat and conquer – against the odds, against authority, against nature, against destiny – famously evolved into Kirk Douglas’ portrayal of the titular militant messiah in Universal Pictures’ Spartacus in 1960. This sword and sandal saga about a humble gladiator rising up to lead the largest ever slave revolt against the imperious Roman Republic was the most expensive and prestigious film production Kubrick had helmed. Furthermore, its subsequent commercial and cultural success helped to solidify his own personal and professional ambitions to be recognised as a leading figure within the industry, a true American auteur.

As Carr explains:

He was at the mercy of an egotistical group of actors (heavyweights Laurence Olivier and Charles Laughton bickering with each other and questioning the authority of this young filmmaker), an equally obsessive producer/lead performer (Kirk Douglas), and the constraints dictated by a film of this size and scope.

This said, as Peter Kramer continues:

[Spartacus] established him as an important player in Hollywood … [enabling] him to negotiate with financiers and distributors from a position of strength so that from then on he could produce medium- to big-budget films … yet made without much interference from them.

The male drive to succeed however is not enough in itself. Such a raw and potentially ruinous emotion needs discipline, direction and order if it is to achieve its aims effectively, reach its destination intact and claim its prize. As a consequence, iconographic tropes such as maps, plans and/or schematics, either handmade or technological, often feature prominently in Kubrick’s mise-en-scène as a visual connotation of the characters’ need for organisation, method and control.

In his first production shot in colour, for example, the 30 minute promotional documentary The Seafarers from 1953, he explores how the Seafarers International Union in Maryland recruits and regulates its mariners, fishermen and boatmen before they work the oceans. To illustrate the scope and influence of this huge endeavour Kubrick pans across a large world map as the narrator asserts: ‘Antwerp, Cape Town, London, Marseilles, Singapore … You name it: picking his destination is the right of every Seafarer.’

More memorably of course is the mesmeric overhead push-in on the scale model of the hedge maze in The Shining in 1980. Restless in the reception hall of the Overlook Hotel, Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) leans over and into it like a disturbed divisional general surveying his battle plans for the next day as his wife and son appear superimposed like mere insects, happily oblivious that they are wandering through a metaphor for their patriarch’s decaying mind.

Indeed, Carr reiterates this recurring Kubrickian conceit in his epilogue when he cites the screenplay for Napoleon, the unrealised biographical epic which many critics agree would have proved to have been the director’s raison d'être, the totality of his cinematic aesthetic:

Scene 31: INT—NAPOLEON’S PARIS HQ—DAY

Pencil between his teeth, dividers in one hand, [Napoleon] creeps around on hands and knees on top of a very large map of Italy, laid out from wall to wall. Other large maps cover the table, the couch and any other available space.

In line with his increased production budgets, abilities and aspirations Kubrick advanced his ruminations on order, control and power considerably with Dr. Strangelove in 1964, 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968 and A Clockwork Orange in 1971. On the one hand these three films can be seen to mirror the theoretical work carried out by one of his 1960s contemporaries, Marshall McLuhan, in terms of technology serving as an extension of man: his physicality, his consciousness, his ethics and his will. And, on the other, it could be argued that they also echo Karl Marx’s position in the 19th century with regards to technological determinism and the hegemonic role this plays in the socio-economic relations and cultural practices of wider society.

For example, the cockpit of the B-52 in Dr. Strangelove is heaving with ‘a smorgasbord of lights, switches, maps, gauges, radars, and guides’ as it transports a hydrogen bomb to its intended Soviet target. The message from the military to the body politic is very loud and clear: everything is under control. We have the technology. God bless America.

With the incomparable 2001: A Space Odyssey the audience, and cinema itself, are invited to take a giant leap forwards as Kubrick propels us from the prehistoric broken bones of homicidal hominids and into the nervous system of the spacecraft Discovery: its intricate network of hibernation pods and plasma pipes, scanners and closed-circuit cameras all interconnected and centralised within the mainframe brain of HAL, the supercomputer whose sole duty is to transport the crew to Jupiter to investigate an alien radio signal. We can only assume that, hypothetically, if this fully-funded, interplanetary mission is successful then it would surely herald the expansion of American political, economic and cultural imperialism out of this world and throughout the cosmos.

Returning to earth with A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick explicitly intertwines technology and hegemony by way of the Ludovico Technique, a state-sponsored behavioural aversion procedure which is tested on one desperate experimental subject: the untamed, ultra-violent rapist droog, Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell). Here scientific research, knowledge and needles are employed by the British Ministry of the Interior to physically inculcate self-control and conclusively cure him of his own destructive free will. The treatment leaves working-class Alex meek and defenceless and, against our better judgement, we are encouraged to feel sympathy for him. Prof. Philip Kuberski argues however that the film’s narrative should not be regarded as a defence of free will at all but instead as a reminder to the audience that we are also ‘conditioned in some way or another’ and the day-to-day freedoms we think we enjoy are just an ‘illusion’.

With this in mind we can thus posit that Kubrick’s driven men, whether they know it or not, are also suffering from a similar existential crisis. That is, their desire to confront, combat and conquer is just that, a desire, and not a logical decision which they are able to make. As a result, their attempts to control and direct their impulses with plans, maps or technology are ultimately unsustainable due to the impermanence and vicissitudes of the wider world, the people within it and the forces in between. Thus, their turbulent and tragic character arcs can only lead their sense of purpose, and their sense of self, to overexposure, disorder and defeat.

In Lolita in 1962, for instance, the upstanding university lecturer Humbert Humbert (James Mason) is ultimately undone by his illicit infatuation with the 14 year old Dolores Haze, deliriously dissolving into ‘a mere shell of himself, totally out of control and forcibly subdued by … hospital staff’.

Redmond Barry (Ryan O’Neal), the self-serving 18th century Irish scoundrel and gambler in Barry Lyndon in 1975, swears that he will never ‘fall from the rank of a gentleman’ but, inevitably, he comes tumbling down the social ladder following a messy duel against his stepson where he loses his leg and is banished from England forever.

Then there is Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey) who, in Full Metal Jacket in 1986, humiliates and belittles his squad of new recruits, stripping them, one by one, of their egos and their dignity in order to transform them into marines, into killing machines who are ‘ready to eat their own guts and ask for seconds’. It is ironic that this brutal training regime proves to be more successful than anyone could of imagined when, during one sleepy evening, the maligned and malfunctioning Private Pyle (Vincent D'Onofrio) executes Hartman, his nemesis, with a bullet to the chest.

As can be seen nearly all of the male protagonists mentioned are leaders and/or patriarchs who, while memorably constructed and beautifully performed, are also narcissistic, naïve, deluded and alone. Consequently, one critical lesson we can learn from Stanley Kubrick’s exceptional oeuvre, as well as from Jeremy Carr’s fine book, it is that as audience members and as mindful citizens we should always be extremely careful about the kind of men we choose to bestow authority, control and power upon in political, corporate and cultural life.

This review was first broadcast on Arts Express by WBAI 99.5FM in New York, see here.‘Kubrick and Control: Authority, Order and Independence in the Films and Working Life of Stanley Kubrick’ by Jeremy Carris available here.