Mike Quille reviews an involving, stimulating exhibition which encourages the growing appetite for cultural democracy.

The recent appointment of Elisabeth Murdoch to Arts Council England was yet more evidence of the increasing domination of public funding for the arts by corporate and right-wing interests.

There is growing resistance, however, among activists and artists. There are also signs that labour movement leaders are becoming more aware of the importance of cultural activities in the lives of their members – see for example Len McCluskey’s Introduction to the Bread and Roses 2017 Poetry Anthology.

The 2017 Labour manifesto also contained some progressive promises around devolving decision-making, increasing funding and boosting arts education in schools. It was a great improvement on previous manifestos, which had become more and more oriented towards art and culture as merely functional for economic regeneration.

It was flawed, though – see here for a cogent critique by Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt. Debates and discussions on the left are growing, and reports, articles and manifestos are being proposed, based on a much more radical approach to arts and culture. For example, see here for the result of discussions at the Momentum-organised The World Transformed festival in Brighton last September. Events are being planned around the country to present and consult on this manifesto, by the Movement for Cultural Democracy.

One of the features of this movement is a belief that the cultural struggle and the political struggle go hand in hand – that culture, as well as being entertaining and enjoyable, is essentially liberating in a political sense. Cultural activities are fundamentally social and equalising, asserting our common humanity against divisions of class, gender, race and other social divisions engendered by capitalism, especially its neoliberal variant. In this view, culture can inspire, support, and accompany radical change in the real world.

There is no better current example of this belief in the power of art to transform the world than the current ‘Revolt and Revolutions’ exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, near Wakefield. A variety of works, linked in various ways, showcase some of the strands of counter-cultural and anti-establishment movements of recent times, and invite us to join in.

At the entrance to the exhibition, The Internationale, as sung by the artist Susan Philipsz, is broadcast in the open air. It calls us in, resonating across the former coalfields and industrial heartlands of South Yorkshire. The faltering, saddened voice conveys both the sufferings endured by the northern working classes in the last fifty years, and their resilience and continuing determination to redress injustice through political action.

As we go inside the gallery, more music welcomes us. Ruth Ewan’s A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World is a selection of classics of political music and song, updated to include songs for the Trump era, which visitors can choose and listen to.

Ruth Ewan, A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World, courtesy the artist and YSP. Photo © Jonty Wilde

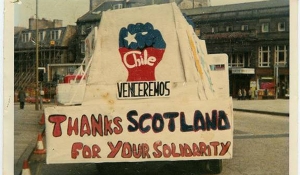

Political music is also celebrated by two arpilleras, a kind of Chilean patchwork quilt, illustrating the key ideals of the New Chilean Song Movement. This was a powerful, persuasive cultural movement which accompanied and assisted the rise to power of Salvador Allende’s socialist government in 1970. One of its main supporters was the singer, guitarist and communist Victor Jara, later tortured and killed by the Pinochet regime. Pinochet’s admirers and allies included Margaret Thatcher, responsible for the privatisation of the local Yorkshire steel industry and the British state’s war against the miners and their socialist leaders, in 1984-5.

Arpillera, New Chilean Song, 1980–83, unknown political prisoner, Chile, and an installation view including Helmet Head 1, Henry Moore, cast 1960. Courtesy YSP, photos © Jonty Wilde

Henry Moore was a socialist and the son of a miner, brought up in a household where meetings of the first miners’ union were held. His works have graced the Park for many years, and in this exhibition his bronze sculpture Helmet Head evokes the exterior toughness and interior vulnerability of hardworking, hard-up men and women.

Revolt & Revolutions, installation view, 2017. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist. Courtesy YSP. Photo © Jonty Wilde

There are many more artworks and a particularly vivid display of photographs expressing the punkish, counter-cultural spirit of the seventies. But the outstanding artwork is a 15 minute video of local resident Alison Catherall, still living in Castleford, birthplace of Henry Moore. It tells the story of the region over her lifetime, from the optimism and pride of the fifties and sixties to the Tories’ assault on the working class communities in the seventies, eighties and beyond, and her determination to crusade for a better life, a transformed world for young people through education, culture and heritage.

She tells her lifestory, from the optimism and pride when she was young in the fifties and sixties, to the Tories’ assault on local steelworking and mining communities in the seventies, eighties and beyond. Her voice rises and becomes impassioned as she talks about her continuing militant determination to crusade for a transformed world – a better life for young people through education, culture and heritage.

Larry Achiampong and David Blandy, FF Gaiden-Legacy, 2017 (film still). Courtesy YSP and Castleford Heritage Trust

This moving oral history of suffering and struggle is illustrated by film of a female avatar, taken from the video game Grand Auto Theft 5, striding through deserted pit galleries, up and down the hilly landscape, by day and by night and through all weathers. The local and particular story of suffering, endurance and resilience becomes universal, an artistic tribute to both local and global working class communities – particularly the experience and struggles of women to keep those communities alive.

This focus on art which comes from the experiences of the many, and is addressed to the many, is carried through not only in the curating of the exhibition – there are several exhibits inviting public participation – but in the events organised around it. For example, on February 20th, the evening of the UN Day for Social Justice, YSP are running a talk on ‘Do You Want to Change the World’ on the relevance of art and culture to the political transformation of society.

Helen Pheby is the senior curator at YSP responsible for the grounded, varied and interlinked themes running through this excellent exhibition. I asked her for some insights into her approach, to share with readers of Culture Matters. This is what she said:

'The inspiration for Revolt and Revolutions came from working with Henry Moore's family and foundation on a previous major exhibition and learning how radical he had been, not just as an artist, but also through his commitment to social justice.

I was conscious that we don't seem to be hearing much good news at the moment and wanted to share works by artists who are trying to make a difference, or who are giving a voice to people in our communities committed to positive change.

My hope was that this small show might be a catalyst, raise spirits and hopes a little, and suggest ways we can all have power. The public response has been very positive, with record visitor numbers in the gallery and people making pledges to make a difference. Our associated events, such as inviting people to change the world, are proving popular, suggesting a real appetite for people to get involved.

Helen’s hopes have surely been realised. By showing and promoting the power of art to change the world, through the exhibition itself and the activities, talks and discussions that run alongside it, Yorkshire Sculpture Park are encouraging the appetite for cultural democracy which is emerging from the labour movement.

Finally, Matt Abbott, the poet, has written this poem to accompany the exhibition. It's best listened to on the link, but here's the text as well:

Revolt and Revolutions

by Matt Abbott

Placard, pin badge, denim, leather.

Fist clenched tight at the end of your tether.

Minds in the margins all come together

the Revolution will not start itself.

When the turn of a phrase is the twist of a knife

and a movement swims at the tide of the strife,

a slingshot points at the status quo

the choir sings a resounding “NO!”:

change, is a product of protest.

Give a soapbox to a voice

that can’t be heard amongst the crowd.

There’s a rebel with a cause,

there’s a dream that’s not allowed.

There’s a sub-group that’s been silenced,

a door that’s slamming shut.

An establishment that works to keep you structured

in a rut.

Where optimism sits with solidarity and strength.

For justice and equality, we’ll go to any length.

Apathy is acceptance. Acceptance never improves.

So stand up, and be counted: we’ve got goalposts to move.

Grab a megaphone, and articulate your grievances.

Strum guitars, paint banners, leave writing on the wall…

In the shadows, is where you’ll find allegiances.

We might be tiny individuals, but together, we’re tall.

Give power to the vulnerable; a voice to the unheard.

Don’t allow the privileged to take the final word.

March longer, sing louder, fight for what is right.

Acclimatise to darkness, and you’ll never seek light.

Revolt, reject, and rejoice in your dreams.

Protest is always more potent than it seems.

Be it beret wearing ‘Ban the Bomb’ or mohawk wearing punk;

others pinched nostrils but we shouted when it stunk.

Revolt and Revolution: come and join the number.

because nothing serves injustice like society in slumber.

Music and colour. Peace signs and love.

There are far more below than there are sat above.

It takes an awful lot of raindrops to form a monsoon.

And this station has a glitch: it’s time to retune.

Do not succumb to victimhood, or silence, or stealth,

because the Revolution will not start itself.

Yorkshire Sculpture Park, near Wakefield, is open 10am till 5pm and the exhibition, which is on till 15 April, is free. You can also visit this exhibition at the same time.