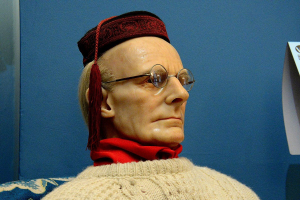

Love, mutual trust and solidarity: Chingiz Aitmatov, the Kyrgyzstan national writer

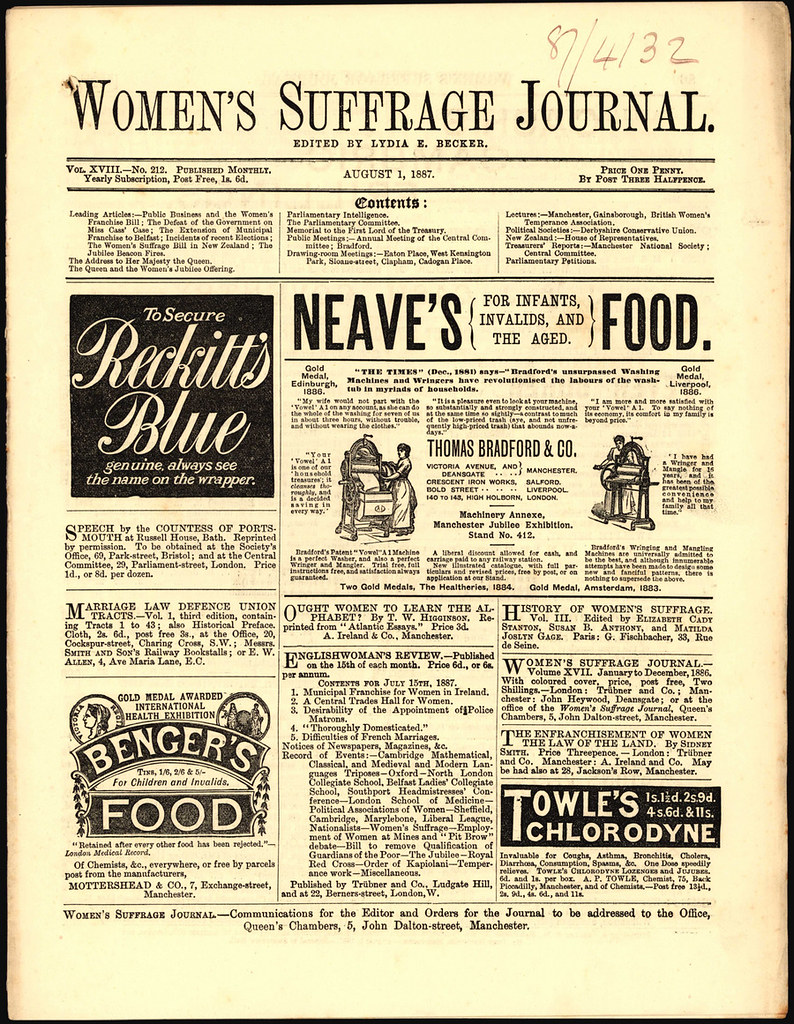

One of the lasting effects of the continuing cultural Cold War against all socialist thought and culture is the West’s denial of the art of socialist countries. This affects all genres in all the socialist countries. The work of these artists is rarely easily available to the general public, and it’s sidelined in university courses, dismissed highhandedly as “Soviet Era” and therefore by definition deplorable.

This article is about the amazing Kyrgyz writer Chingiz Aitmatov, who died fifteen years ago, on 10 June 2008. Aitmatov was very well-known throughout the socialist world and was the principal reason for my recent visit to his homeland, Kyrgyzstan. The Lonely Planet guidebook I had brought with me unsurprisingly made no mention of the country’s national writer.

Over eighty per cent of Aitmatov’s Central Asian homeland lies in the high Tian Shan mountains (Chinese for “Celestial Mountains.”). Kyrgystan’s landscape consists for the most part of mountain steppes, valleys at an altitude of 1500 to 2000 metres, populated into the 20th century by mountain nomads with an extraordinarily vital oral tradition. Until the establishment of Soviet power, the language had no alphabet and illiteracy prevailed. Consequently, the oral tradition epics of this people survived into recent times and remain significant for the historical consciousness of the nation. The written language was only introduced in the early 1920s, a few short years before Chingiz Aitmatov’s birth. The first great flowering of Kyrgyz literature began with this author. His work made his homeland, its people and its nature known and loved far beyond its borders.

Born in 1928 in the village of Sheker in Kyrgyzstan, Chingiz Aitmatov came into contact with the nomads of his homeland at an early age through his grandmother and so became acquainted with their myths and legends. In 1935, the family moved to Moscow, where his father was one of the first Kyrgyz communists to study as a party functionary at the CPSU’s social science cadre university, the Institute of Red Professors. Chingiz thus grew up bilingual. Both parents awakened in him an interest in and enjoyment of Russian and Kyrgyz literature and art. However, in 1937, his father became a victim of Stalin’s terror. He was arrested, executed by a firing squad in 1938 along with 137 other Kyrgyz intellectuals and buried in a mass grave in Chong-Tash village, 25 kilometres south of the capital Bishkek. Aitmatov, who named this graveyard Ata Beyit (Grave of Our Fathers), chose to be buried in this same location.

Following her husband’s arrest, Chingiz’s mother, a Tatar, returned with the children to their native village, where despite being the family of an alleged “traitor”, she was supported by the village community. After the war began, young Chingiz was given a position in the district administration in 1942 and, like other young people, had to leave school at the age of fourteen. He went back to school after the war, studied at the veterinary college and began to write. His veterinary training was followed by five years of study at the agricultural college and work as an animal breeder.

In 1956, he went to the Maxim Gorky Institute of Literature in Moscow and attended a two-year course for young authors. His first stories appeared and in 1958 he wrote his world-famous novella Jamila for his graduation submission. Many more stories and novellas followed, written both in Kyrgyz and Russian.

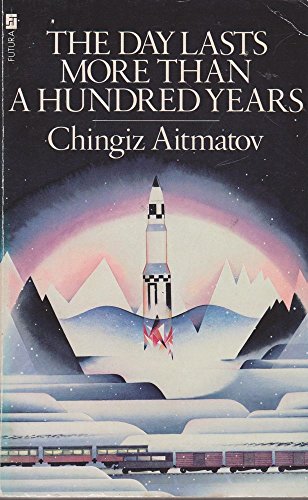

Kyrgyz epics and legends repeatedly play a major role in his work. In 1980, Aitmatov’s great novel The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years was published. Due to its at times controversial subject-matter and also the inclusion of tragic elements, Aitmatov’s work often came under criticism. However, his outstanding literary achievement was also honoured with several high awards.

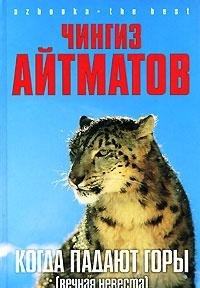

Aside from writing fiction, Aitmatov was actively involved in politics and worked as editor-in-chief of the newspaper Literaturnaja Kirgizija (Literary Kyrgyzstan) and for Pravda as correspondent for Kazakhstan and Central Asia. At the end of 1989, he became one of Gorbachev’s advisors, in 1990 the USSR’s ambassador to Luxembourg and from 1995 the Kyrgyz Republic’s ambassador to the European Union. Further stories were published, as well as his memoirs “Childhood in Kyrgyzstan”, in 1998. In his last novel, When Mountains Fall (2006, not translated into English), Aitmatov again combines an old Kyrgyz legend with the reality of the post-socialist 21st century.

When Aitmatov was awarded the Aleksandr Men Prize in 1998, he declared:

Humanity has no more comprehensive and no more complicated task than that of bringing forth a culture of love for peace as a contrast to the cult of violence and war. There is no area of human existence - from politics to ethics, from primary school to high science, from art to religion - where the human spirit is not confronted with the universal idea of the renunciation of violence.

Chingiz Aitmatov died in Nuremberg on 10 June 2008 at the age of 79.

The solidarity of ordinary people

Aitmatov’s novel The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years is set in the Kazakh steppe at an inhospitable eight dwelling railway junction not far from the Cosmodrome. The junction’s name, Boranly-Burannyi (snowstorm), refers to the rough life and weather that the small village community face, and confront together. However remote, it is spared neither national nor international upheavals. The inhabitants come to this wasteland for different reasons, and not everyone is cut out for the hardships of life there. The death of one of the two people who have spent their adult lives here, Kazangap, prompts his closest friend, Burannyi Yedigei (Snowstorm Yedigei), to honour ancient tradition and bury him in the ancestral graveyard. To do so, he saddles and decorates his legendary camel and sets off with Kazangap’s closest relatives and the digger Belarus.

The novel describes Yedigei’s memories and experiences on his way to the cemetery. It is the day that transcends Kazangap's life and reflects on the times. Thinking as a specifically human ability is reflected upon at all plot levels: “Yes, the Sarozek [the steppe] was vast, but the living thoughts of a person could contain even this.”

Aitmatov condenses the action by linking two storylines – one set in the immediate present as well as one set in the early 1950s – with various references to the life stories of the novel’s main characters. To this are added Kazakh myths as well as a USSR-US space cooperation programme that has a utopian dimension, but also takes place in the present of the novel. A fabric emerges in which the past and the future intertwine, in which the best and the most horrendous things that human beings are capable of emerges, as well as the possibility of intergalactic cooperation with a civilisation that is more advanced and peaceful than Earth’s inhabitants.

The theme of peaceful community, human strength and the solidarity of ordinary people runs through all plot levels, as does the potential to destroy other humans. The legends are about power and abuse of power, violence and resistance. The legend of the Mankurt is centred on the erasure of memory and the subduing of those who survive cruel torture. But it is also about a mother’s fight for her son. Parallels are drawn with Stalinism, which is depicted here in the fate of the family of Abutalip and Zaripa Kuttybayev, and in which Aitmatov undoubtedly creates a monument to his own father.

Nevertheless, manifestations of goodness are also found again and again. Aitmatov’s positive characters are characterised above all by their love for other people, for children, for animals and for nature. Violations of this elementary love are, as it were, offences against humanity. At the same time and closely connected to this is their sense of responsibility for the important work that defines their lives. People of different origins and fates have ended up at this remote railway junction in the middle of the steppe, people for whom work and life here offered a new beginning despite all the hardships. Here, they harness all their strength to ensure that the trains can travel from West to East and back. They celebrate the New Year together in this scene:

Yedigei honestly believed that he was surrounded by inseparably close friends. Why should he have believed otherwise?

For a moment, in the middle of a song, he felt he had to close his eyes. He saw in his mind’s eye the vast, snow-covered Sarozek and the people in his house, all come together like one family. But most of all he was glad for Abutalip and Zaripa. (...) “Zaripa sang and played on the mandolin, quickly taking up the tunes of the songs, one after the other. Her voice was ringing and pure. Abutalip led with a deep-chested, muffled, drawn out voice. They sang together with spirit, especially the Tartar songs. These they sang in the almak-calmak style, one singer answering the other. As they sang, the other people joined in. They had already sung many old and new songs (...) Sitting opposite Zaripa and Abutalip, Yedigei looked at them the whole time and was moved. They would always have been like this, were it not for that bitter fate which gave them no peace of mind.

And further blows of fate await them, which Aitmatov deepens by weaving in three legends, each with special relevance to the main characters: the power of love and its tragic failure. This failure is repeatedly rooted in the power of inhuman opponents, the absence of solidarity and weakness of fellow human beings. Therein lies the tragedy.

The space travellers represent the two great powers, here cooperating in a unique joint project to explore a newly discovered planet with inestimable mineral deposits for the purpose of energy production. With the great self-sacrifice of Aitmatov’s heroes, they try to persuade their governments to be open to the new civilisation:

At present they still have several million years yet to live on their parent planet, and we found it remarkable that they have already been thinking about a time so far ahead in the future and are filled with the same fire and energy about it as if the problem affected the present generation. Surely the thought has arisen in many minds, ‘Will the grass not grow when we are gone?’ (...) But the remarkable thing is that they do not know of states as such; they know nothing of weapons; they do not even know what war is. We do not know; perhaps in the distant past they had wars and separate states and money and all the social factors of a similar character; but at the present time they have no conception of such institutions of force as the state and such forms of struggle as war. If we have to explain the fact of our continuous wars on earth, will it not seem inconceivable to them? Will it not also seem a barbaric way of solving problems?

Their life is organized on quite a different basis, not completely comprehensible to us, and quite unachieved by us in our stereotyped earth-bound way of thinking.They have achieved a level of collective planetary consciousness that categorically excludes war as a means of struggle, and in all probability theirs is the most advanced form of civilization among rational beings in the universe.

Understanding our common humanity

The perversion of mutual support and the dissolution of social cohesion in the interest of money thematically determine Aitmatov’s last novel When Mountains Fall. Cash nexus now rules where trust, mutual respect and help used to be. The snow leopard, a protected species, a symbol of the high mountain regions of Central Asia and revered there since time immemorial, is sacrificed to Mammon, even if this means the destruction of the region’s soul in the immediate future. The old values of a symbiosis between humankind and nature are sacrificed.

Some previous collective farmers are now calculating businessmen, a former gifted soprano has become a pop star, the erstwhile veterinary surgeon has switched to dog breeding, exporting the wolf dogs that are in demand in Europe, mainly to Germany. The majority of the population is struggling to survive: a past teacher is now a horse herder, a librarian is a flying trader, the protagonist, the journalist Arsen, is self-employed and is threatened right at the beginning of the novel. Driven into a corner and, unlike the leopard, informed about a society now hostile to him, he seeks revenge. But when he is actually able to take revenge, his humanity wins out, even if it costs him his life.

Once again, Aitmatov interweaves an old legend – that of the Eternal Bride – with contemporary events. On the significance of this myth, Aitmatov said the following in an interview about his novel:

This is a great, tragic material. The forces of evil have destroyed the great love that was between two young people. Shortly before the wedding, guileful villagers kidnapped the bride to thwart their happiness. They told the groom that the girl had run away with a rival. In despair, he disappeared into the mountains. Afterwards, the people realised their mistake and regretted it. Too late. The fact that this myth is still alive today, that our people still believe that the Eternal Bride wanders around looking for her groom, that people light fires for her on certain nights, even prepare horses for her, shows how great this remorse and grief are.

In this novel, too, three plot levels are linked. Alongside the present-day level of human experience at a turning point in time, there is secondly the myth, and thirdly, the author writes from the perspective of the snow leopard itself. All three levels enrich each other. As Aitmatov frequently does in his writing, he describes this animal species sensitively and from its own point of view.

Aitmatov’s view of humanity is marked by tragic features. Nevertheless, it is not dystopian. With his work, he sharpens readers’ awareness of the strengths of humanity: love, mutual trust and solidarity. And he describes how these are mercilessly destroyed by inhuman enemies. By putting us in the shoes of the ordinary people of Central Asia, we understand even more deeply our common humanity, which we must defend and protect in common cause. It will not be easy.