Shelley was born shortly after the French Revolution, heir to a substantial estate and also to a seat in Parliament, on 4 August 1792 in Sussex, England. As a son of the upper classes, he attended Eton College and was subsequently enrolled at Oxford University. Britain was in political turmoil in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with food riots, Luddite rebellion, unrest in Ireland, the threat of Napoleon’s armies and a growing bourgeois reform movement.

The ruling class feared the example set by the French might infect their own working class and reacted with repression. The young Shelley took part in campaigns for the release of imprisoned democrats and worked to create an association of radical democratic people. At Eton he began to write and also to express atheist views. Atheism was deemed infinitely more dangerous in repressive Britain than the suspect Dissenters and Catholics. In 1811 Shelley was expelled from Oxford University and disowned by his family for publishing The Necessity of Atheism.

The Necessity of Atheism is one of the earliest treatises in England on atheism and argues that since faith is not governed by reason, there is no evidence for the existence of a God. The universe could always have existed and if there had been an initial impetus, it need not have been a God.

This text led to his exclusion from the circles of power to which he was entitled by birth. In the same year, Shelley also eloped at the age of 19 with Harriet Westbrook, three years his junior, and married her in Scotland. This led to further estrangement from his family, as well as from the Westbrook family.

Shelley and women's issues

Shelley was a follower of the radical publicist William Godwin, author of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), who argued among other things, for gender equality and against the marital morality of the time. Both Godwin and Shelley respected the views of the women around them, which included unmarried couples, as well as independent women who worked and raised their ‘illegitimate’ children. Shelley rejected marriage as deeply misogynistic and was one of the early advocates of women’s emancipation.

In February 1812, Shelley and Harriet sailed to Dublin. Here they campaigned vigorously for the emancipation of Catholics and the abolition of the Union. As early as 1811 Shelley had written a “poetical essay” in support of the imprisoned Irish journalist Peter Finnerty, a former editor of the United Irishmen’s journal, The Press. In preparation for his campaign in Ireland, Shelley had penned An Address to the Irish People. His second pamphlet, Proposals for an Association, even appealed to the remaining United Irishmen to give Irish politics a more radical direction by peaceful means. Shelley was a great admirer of Robert Emmet and the United Irishmen and wanted to form an association that openly worked towards an egalitarian republic, supported legal equality and freedom of the press.

He also had a Declaration of Rights printed in Dublin in the tradition of the American Revolution, distributed it and appeared at various events. Together with John Lawless, an associate of Daniel O’Connell, he planned to found a radical newspaper and publish a new history of Ireland. Shelley advocated peaceful means throughout his life, despite Godwin’s disapproval that he was planning “bloody scenes”. Nevertheless, he realised that he had to go beyond Godwin and Paine.

The Shelleys moved to Wales to agitate for better conditions among the agricultural workers. This even led to an assassination attempt on Shelley in early 1813, probably instigated by the landowner Robert Leeson, son of one of the wealthiest Ascendancy families in Ireland, whereupon Shelley fled from Wales back to Ireland.

There, in the seclusion of Ross Island in Killarney, he completed his first major verse narrative, Queen Mab, and returned to London shortly afterwards. Here he met with Godwin, whose An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice alongside Rights of Man, by Godwin’s friend Thomas Paine, had become one of the best-known political pamphlets in England. Godwin’s wife Mary Wollstonecraft, who died in childbirth, had written A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a foundational document of the early women’s movement, following Paine’s Rights of Man.

Shelley’s relationship with Harriet had become difficult. In 1814 he fell in love with Godwin’s daughter Mary and fled with her to war-torn France and Switzerland at the end of July; they returned in mid-September. In November 1814 Harriet gave birth to a son, and in February 1815 Mary Godwin delivered a premature daughter who died days later; the following January Mary had a son. Byron left England at the end of April 1816. Shelley and Mary followed him to Switzerland in May.

In December 1816, Harriet Shelley committed suicide by drowning, pregnant again by another brief relationship. Shelley, who had continued to care for Harriet, then married Mary Godwin. He lost custody of his two children when Harriet’s family cited Queen Mab as evidence of his atheism and rejection of marriage. The children were placed in the care of a clergyman. The deaths of two more children left deep scars and as late as June 1822, a few weeks before Shelley’s death, Mary miscarried and nearly died herself.

In March 1818, the Shelleys emigrated to Italy. In the remaining four years of his life in exile, Shelley wrote his major works. Two hundred years ago, on 8 July 1822, Shelley drowned in a sailing accident. Condemned by conservative critics as an immoral outsider, he did not live to see the bourgeois-democratic and burgeoning proletarian movements take possession of his work.

Shelley's socialism

Eleanor Marx continued Marx and Engels’ Shelley enthusiasm. In her Shelley lecture, she answered the question of Shelley’s socialism as follows:

Shelley was on the side of the bourgeoisie when struggling for freedom, but ranged against them when in their turn they became the oppressors of the working-class. He saw more clearly than Byron, who seems scarcely to have seen it at all, that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes.

Moreover, Eleanor Marx underlines the influence on him of Mary Shelley and her mother, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft:

All through his work this oneness with his wife shines out (...) The woman is to the man as the producing class is to the possessing. Her “inferiority,” in its actuality and in its assumed existence, is the outcome of the holding of economic power by man to her exclusion. And this Shelley understood not only in its application to the most unfortunate of women, but in its application to every woman.

Love was a central category in Shelley’s thinking. In open rebellion to the norms of bourgeois aristocratic society and the Church of his time, love is the capacity for true humanity and the purpose of human life. With this core category, his poetry expresses a concrete utopia: what is conceivable becomes a possibility and inspires action to bring about this vision. Love requires solidarity and action against the enemies of humanity. In this sense, Shelley’s utopia was perceived as anti-religious and subversive.

Completed in 1813, Queen Mab, a blank verse narrative, has the character of a poetic credo and a political poem. In a cosmic dream journey, the fairy queen reveals to young Ianthe the misery of humanity in history and the present. Shelley emphatically rejects religious arguments of something intrinsically ‘sinful’ in humankind and cites the real culprits:

Man’s evil nature, that apology

Which kings who rule, and cowards who crouch, set up

For their unnumbered crimes, sheds not the blood

Which desolates the discord-wasted land.

From kings, and priests, and statesmen, war arose,

Whose safety is man’s deep unbettered woe,

Whose grandeur his debasement. Let the axe

Strike at the root, the poison-tree will fall;

And where its venomed exhalations spread

Ruin, and death, and woe, where millions lay

Quenching the serpent’s famine, and their bones

Bleaching unburied in the putrid blast,

A garden shall arise, in loveliness

Surpassing fabled Eden.

Shelley becomes even more specific, naming “the poor man” as his own liberator: “And unrestrained but by the arm of power,/ That knows and dreads his enmity.” Only people committed to reason and to love are able to realise a humane future, which includes the free association of women and men. In his notes on Queen Mab, he further underlines the insights quoted here:

Kings, and ministers of state, the real authors of the calamity, sit unmolested in their cabinet, while those against whom the fury of the storm is directed are, for the most part, persons who have been trepanned into the service, or who are dragged unwillingly from their peaceful homes into the field of battle. A soldier is a man whose business it is to kill those who never offended him (…)

The poor are set to labour, – for what? Not the food for which they famish: not the blankets for want of which their babes are frozen by the cold of their miserable hovels (...) “no; for the (…) false pleasures of the hundredth part of society.

This poem was so enthusiastically circulated among radicals and the rising working class that it became known as the “Bible of the Chartists”.

After the war with Napoleon ended, Britain was hit by a new wave of mass unemployment, food riots and new state reprisals. The Holy Alliance’s struggle against all emancipation efforts on the continent led to a desperate search among radicals for new means of resistance. When Mary and Shelley met Byron in Switzerland in the summer of 1816, a new phase in Shelley’s work began.

In Hymn to Intellectual Beauty, beauty has left this “dim vast vale of tears, vacant and desolate” and “No voice from some sublimer world hath ever/ To sage or poet these responses given”. Only when “musing deeply on the lot/ Of life (...)/ Sudden, thy shadow fell on me”. No religion can bind beauty as a vision of a humane society to the ‘vale of tears’; only one’s own thinking can evoke it. Beauty is as anti-religious and deeply connected to a humane society for Shelley as it was for his contemporary and friend John Keats, also one of the revolutionary Romantics.

Revolution and counter-revolution

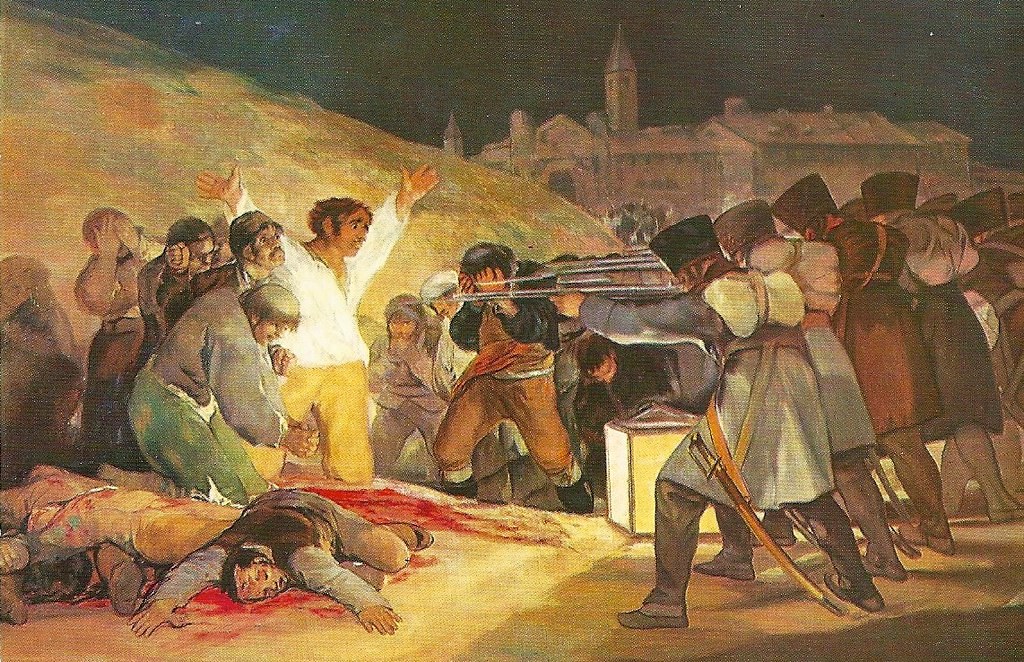

The theme of Shelley’s longest verse narrative, Laon and Cyntha (The Revolt of Islam), is the French Revolution. Building on visions from Queen Mab, it develops its great historical subject through the plot. Two lovers inspire a revolution against the Turkish Sultan. The course of the French Revolution is symbolically represented in the action of the lovers: Laon and Cythna are revolutionaries. Laon inspires resistance against the soldiers who capture Cythna. Sailors rescue her and she persuades the sailors to release their cargo of female slaves, which becomes an act of self-liberation. Cythna is celebrated as a folk heroine.

Together with Laon, she plays a leading role in the revolution that overthrows Othman. The revolutionaries spare Othman, who then instigates a counter-revolution and massacres the people; famine and epidemics follow. The Christian priest, in league with Othman, persuades the people to sacrifice Laon and Cythna. Laon asks for Cythna to be spared, Othman breaks his word and Cythna is burnt at the stake along with Laon. Although Laon tells the story, Cythna makes the most impassioned speeches, arguing that the revolution will one day succeed.

Shelley portrays the revolution as little bloody, but the counter-revolution as brutal. In the preface, Shelley refers to the emancipatory aim of poetry. In his effort to combat the disappointment following the hopes of the French Revolution, and through his explanation of the historical as well as social causes of its bloody character, he reaffirms its ideals.

Thus he also justifies the bloodshed of the insurgents as forced by their oppressors. Despite intensified repression, Shelley not only defends the French Revolution, but also addresses issues regarding the role of the artist in struggle. He highlights the sensual, concrete equality of women and men by emphasising their common struggle, which is part of their love. In his preface, Shelley writes: “There is no quarter given to revenge, or envy, or prejudice. Love is celebrated everywhere as the sole law which should govern the moral world.”

In the poetry and prose written in Italy from 1819 onwards, Shelley reached the peak of his achievement. He produced his best-known poem, Ode to the West Wind, the lyric drama Prometheus Unbound, Song to the Men of England, and The Mask of Anarchy, one of the greatest political protest poems in the English language.

The Peterloo Massacre (August 1819) aroused in Shelley the hope of resistance and he wrote with renewed vigour. With the Prometheus drama he hoped to kindle revolutionary fire and continued to insist on his revolutionary core, the need for a humane society. In this drama, he shapes a complex reality, a condensation of everything written so far, and it takes familiarity with Shelley’s world and language to fully unlock the meaning of this work.

Shelley expanded the immediate classical-mythological reference from Greek mythology and its later interpretations through to Milton, as well as elements of his own. Added to this is the Christian world of ideas, whereby Shelley, through his radical humanisation, undertakes an inversion of the biblical story. Thus there is a consistent reference to the present. Prometheus, representative and protector of humanity, is directly connected to nature as a child of Mother Earth; he is her consciousness taken shape. As the epitome of humanity, he has foresight.

Prometheus is bound, powerless and suffering because he is separated from Asia, who represents Love; he needs her as she needs him. His revolutionary revolt against violent oppression is doomed to fail without love. Jupiter, through Mercury, tool of the rulers, can expose Prometheus to the Furies. Prometheus knows when Jupiter’s hour has come; he can endure his sufferings until then. But Prometheus must become active himself, which only becomes possible after the union with Asia, which in turn releases a force immanent in nature and society in the figure of Demogorgon. This triggers Jupiter’s fall from hell and, in a reversal of the Christian legends, Prometheus, bound to the rock, is redeemed by Herculean power. Paradisiacal beauty can now blossom on earth. Prometheus and Asia wed and unite.

Nevertheless, the force of nature, Demorgogon, warns at the end of humanity’s capacity for despotism: “Man, who wert once a despot and a slave,/ A dupe and a deceiver!” He then names love as the healing force:

This is the day which down the void abysm

At the Earth-born’s spell yawns for Heaven’s despotism,

And Conquest is dragged captive through the deep;

Love, from its awful throne of patient power

In the wise heart, from the last giddy hour

Of dread endurance, from the slippery, steep,

And narrow verge of crag-like agony, springs

And folds over the world its healing wings.

In A Defence of Poetry, Shelley writes about the power of poetry, its social role and the responsibility of poets. This power of poetry is expressed in the great Ode to the West Wind, Shelley’s metaphor for the advance of historical movement:

... Be thou, Spirit fierce,

My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like wither’d leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguish’d hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawaken’d earth

The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

Poems such as The Mask of Anarchy and Song to the Men of England speak directly to the struggling workers and became an integral part of the culture of the labour movement. Although Shelley did not advocate armed struggle, he also knew that at times it was unavoidable:

V

The seed ye sow, another reaps;

The wealth ye find, another keeps;

The robes ye weave, another wears;

The arms ye forge, another bears.

VI

Sow seed—but let no tyrant reap:

Find wealth—let no imposter heap:

Weave robes—let not the idle wear:

Forge arms—in your defence to bear.

Next to Burns, Shelley had the greatest influence on 19th century working-class literature in England. His vision applies undiminished today.