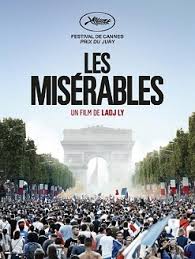

Artwashing at Cannes film festival: 'The best lack all conviction while the worst are full of passionate intensity'

Dennis Broe is unimpressed by the artwashing at this year's film festival at Cannes. Image above: Lou Reed et. al. in Todd Haynes' The Velvet Underground

It may be a bit cruel starting with Yeats’ criticism of his era in his epic poem The Second Coming but unfortunately it is an accurate summary of both the organization and the films in the 2021 edition of the world’s leading film festival.

This post-COVID confinement version of the festival featured maximum healthcare restrictions for the Cannes elite and minimum restrictions for everyone else. Thus to enter the Palais where the competition screenings are held amid the splendour of the red carpet, you are required to have either a QR bar code proving two-shot vaccination in France or a 48-hour COVID test. It is mandatory in France to wear a mask inside but for the opening ceremony, attended by the rich and powerful from the French Riviera and the global 1 percent, both Variety and Screen reported that as soon as the lights went out many of the elite removed their masks and were not reminded by ushers to put them back on.

Meanwhile, for the majority of screenings stocked with lower level press and students, many of which have now been moved out of Cannes and are a 45 minute bus ride away, there were no health restrictions.

This year the entire festival bureaucracy has moved online which caused much initial chaos. Although the streaming services and their digital monopolies are being kept at a distance and not allowed entry into the main competition, the virtual rules the festival. All tickets are online in a system that often crashes, contains no summary of the 135 films in the festival now that the festival book is eliminated, and shortcircuits the human contact of waiting with other dedicated filmgoers.

The online system has, like French organization as a whole, the appearance of elegance while being both inefficient and overly rule bound. What makes it work is that the French people staffing the festival are able to help as they can, humanizing this mechanization just as they have always done with earlier versions of French bureaucracy. But once the system is automated, those lacking technical expertise are practically useless.

What used to be the press room still exists but this year there are no computers, since the usual sponsor Hewlett Packard dropped out. The room is nothing but a series of electrical outlets and remains most often empty. It’s a perfect symbol of the fate of the press over the last decade as hedge funds buy up newsrooms, deplete the staff and sell off part of the real estate, gutting major papers.

In a rapidly deteriorating world, plagued by multiple pandemics involving climate change, COVID, drugs, inequality and racism, the usual blather about the sanctity of the auteur sounds simply like French industry speak, since the films they make seldom confront these problems. Instead, French film makers are using this year’s edition to relaunch their films now backlogged from COVID, with over 450 films vying for attention as they are poured onto the market after the lockdown and facing the American streaming services who used the lockdown to launch their films online.

Because of the restrictions there is also very little product or presence here from the BRICS countries of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, which together account for 40 percent of the world’s population. These countries have been effectively shunted aside what is supposed to be a global festival.

The best are well-intentioned but empty

The best do not lack all conviction but much conviction is shunted aside or squandered in NGO gobbledygook such as that used by Chadian director Hahamet-Saleh Haroun. He makes very good films like The Screaming Man about poverty in neo-colonial Africa, but told the Western press that he was not Chadian but rather he spoke ‘the global language of cinema’.

A special section called Cinema for The Climate is well-intentioned but somewhat empty. At this point if that cinema is not exposing the fossil fuel companies or industrialized fishing magnates which are destroying the land and the oceans it is really engaging in cultural greenwashing, which instead of combatting these companies usually proposes individual solutions to the global problem. An example is the film Bigger Than Us about a teenager from Bali whose Bye Bye Plastic campaign got the island to ban plastic bags, straws and Styrofoam cups. It’s helpful but hardly controversial, and we are beyond the point where planting trees and recycling will solve the problem.

The Gravedigger’s Wife

The best film entry was a fourth level competition film The Gravedigger’s Wife, about a Somali villager who has only a shovel to earn his daily bread, by pursuing hearses and offering to bury the dead. His wife has kidney failure and will die if he does not come up with 5000 American dollars, a sum no one he knows possesses. The film is touching about his and her desperation and in the end, just as all seems lost because a doctor will not perform the operation to save her without the money, a contemporary miracle occurs.

The film, which seems to be about individual heroic acts and acts of kindness, actually calls attention to the need for a global system of healthcare, rather than relying on the kindness of strangers, though it stops at merely validating the miraculous individual act. The film originates in the West, and the Finnish-Somali actor Omar Abdi, whose tattered face fits in with the actual villagers, is excellent. His wife is played by a Canadian Somali model, and her bearing and looks are sometimes a jarring reminder of the presence of the Western gaze, even in a quasi-neorealist film.

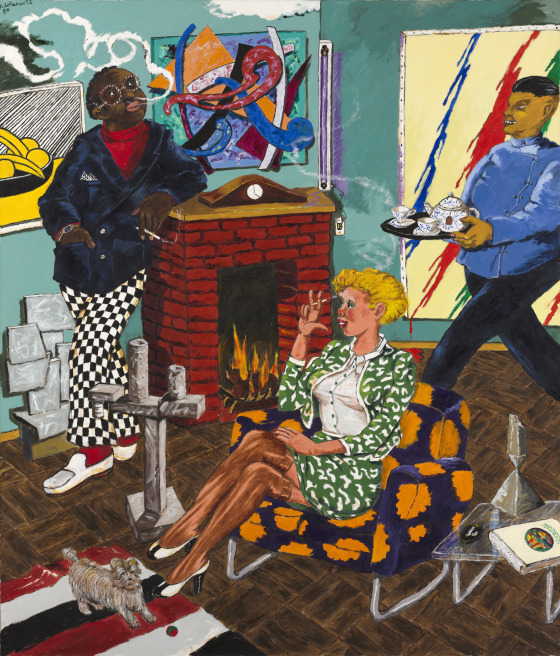

Todd Haynes’ documentary The Velvet Underground is about a band who had few convictions to begin with. Haynes tells the story of this proto-punk group of misfits, outsiders who railed against the musical establishment, which at that time was the industry’s embrace of the hippie era and the Velvet’s West Coast avant-garde rivals Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention.

Their story is told largely in their own words with the avant-garde composer John Cale, whose atonal drone was an essential part of the music, as a major source for the film. The band was supported by Andy Warhol and sometimes described as his marionettes, but the real genius was a drug-addled, bisexual Lou Reed. He channelled all his obsessions into a music that, in its cynical embrace of his truth, linked to the French poets Baudelaire, Verlaine and especially the tortured youth Rimbaud while anticipating the impending return-to-basics musical revolution that was to come, here symbolized by punk-folkie Jonathan Richman, who saw the band in Boston 75 times.

A fascinating recounting of a group of visionary artists, too many of whom, including Reed and the German vocal enchantress Nico who blazed the path for Debbie Harry and Blondie, died young, victims of a society which did not tolerate their alternative lifestyle.

The worst are full of sound and fury

‘The worst are filled with passionate intensity’ might have been Yeats’ review of the festival opener Annette, which Le Monde, doing its part to restore French cinema, gave its highest rating, four stars. Leos Carax is a talented director who makes arthouse films that are, depending on your taste, highly provocative (The Lovers on the Bridge) or fairly pretentious (Holy Motors).

A devilish Adam Driver and a bedevilled Marion Cotillard in Annette

His latest film stars Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard as a disparate couple who combine American low art and entertainment – he is a stand-up insult comic whose stage routine is not funny – with Continental high art as she is an opera singer. The form of the film is operatic, mostly sung, with a soundtrack from the group Sparks. Carax updates the form – in one scene having Driver and Cotillard singing while he pleasures her, and begins both the film and the festival with the ditty “And so may we start,” the lyrics of which, like most of the songs, are simply a repeat ad nauseam of that line long after it has lost its referential meaning.

The film makes use of Driver’s talents and rehearses his past roles, as a robed boxer about to go onstage shot from behind and looking like his Vader character from Star Wars, as out of control lover from Girls in the sung sex scene, and as employing his gorgeously melodious voice which was the revelation of A Marriage Story. Onto a Hollywood tragedy – the boating death of Natalie Wood often attributed to her husband Robert Wagner – Carax grafts a criticism of the vacuousness of American entertainment in the form of the Driver character’s brutality in his treatment of the underused Cotillard.

However, the film exaggerates the brutality, defining it too often as coarseness rather than as violence, while at the same time not showing enough of it, as Scorsese does in the much better New York, New York. It offers Carax’s knowing genre play and thematic overloading as the answer instead of an actual critique of the way French and continental high art and Hollywood are now moving toward becoming a more seamless whole in which neither allows the real problems of the world an airing. Annette is full of sound and fury but signifies little.

Falling into the same category was The Hill Where Lionesses Roar, which features three teenagers discontented with their lives in a Kosovo, which has been almost entirely cleansed of all its meaning as brutal site of destruction – the only signifier of its history is a mosque in the background. Instead the film is mostly about the three teens frolicking – on a hill, in the water, in a hotel. And that’s about the beginning, the middle and the end of it.

Menacing Croatian patriarchy in Murina

On a similar young girl coming-of-age theme was the more interesting Croatian film Murina which features a 17 year old caught in a death grip between a domineering father and his seductive former boss, a successful businessman. The father is trying to induce the businessman to invest in a hotel on the prosperous Dalmatian coast, now a dazzling global resort. The daughter is ultimately able to transcend both the physical violence of the father and the seductiveness of the boss, which since it is empty is a kind of emotional brutality. However, neither is linked to the history of the brutality of a country with a fascist and ethnic cleansing past. This past is being erased as it enters the global economy as tourist paradise.

Similarly interesting and similarly limited was the Argentinian film The Employer and The Employee, invoking Hegel’s master and slave dialectic as it plays out in the parallel relationship of the son of a wealthy landowner and the Indian boy he and his father treat as a servant. In the end the Indian gets his revenge expressed in a bitter smile, but the revenge also dooms him in a way that incorrectly suggests that the only way out of this relationship is mutual self-destruction.

The antidote was provided in a passage from a documentary essay Mariner of the Mountains about a Brazilian journalist Karim Ainouz who journeys to Algeria in search of his father’s village. He quotes Franz Fanon’s passage from his essay on violence that says that when the colonized realizes he or she is equal to the colonizer, it is the beginning of the end of that relationship. We then see Algerian youth chanting “Murderous regime” as they come to their own realization about a government that is selling them out. Here the passionate intensity is directed and purposeful and the conviction of the youth of this generation is sincere.