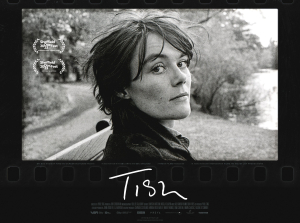

Grim, glorious visions of broken Britain: a review of the film 'Tish', and the photography of Tish Murtha

Brett Gregory reviews 'Tish', directed by Paul Sng, 2023, and presents some of Tish Murtha's photographs

'My use of photography and the approach to it is based on the conviction that the fundamental value of the medium is its capacity to provide direct, accurate and vital records of the conditions, events and experiences that shape our lives.'

This is a quote from one of Patricia ‘Tish’ Murtha’s essays as narrated by Maxine Peake in Paul Sng’s observational and performative documentary, ‘Tish’, from 2023. In turn, it can be understood to be at the core of her socialist agenda as a working-class photographer and social realist documentarian.

As a 52-year-old working-class filmmaker myself, it’s depressing to see that the desolate council estate where she was raised in Elswick, Newcastle, was very similar in style and content to the miserable maze of treacherous terraced houses where I grew up in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire. Places where poverty, illiteracy, alcoholism, drugs, child abuse, domestic violence, vandalism and boredom were the main attractions.

Ex-Miner, New Found Out Pub, Newport, 1977 © Ella Murtha. In 1976 Tish Murtha, with support from her tutors Dennis Birkwood and Mick Henry, secured a funded place on a photography course at Newport College of Art and Design run by David Hurn. The New Found Out Pub on Cambrian Road in Newport was notorious for serving lumpy cider.

While the working-class residents of Elswick were ravaged by the descent and dismantling of the steel and shipbuilding industries during the latter part of the 20th century, Mansfield, a mining community, was decimated and deformed by the Thatcher-led pit closures in the early to mid-1980s. This mining community had been composed almost entirely of regional migrants, particularly from Scotland, Wales and, coincidentally, Tyneside. Indeed, the older lads I sometimes hung around with outside the local shops during my mid-teens – Carl, JJ, Biddy, Kev and Mozz – were all Geordies.

In the summer of 1985, I remember that JJ saved up enough money to get a tattoo of his beloved Newcastle United on his arm, but when he peeled the scab off after a few days it read ‘Newcastle Uniten’ instead. It seemed that even the tattoo artist in town was illiterate.

Anyway, we all laughed and poked fun at him, and he told us to ‘Ga'an away or a'll boot the shite oot ya!’ before storming off home. A week later and he then triumphantly reappeared outside of the shops, pulled up his sleeve and revealed to us that ‘Uniten’ was no more, had never even happened, for it had now been replaced by a new tattoo of a big red rose. I asked him what the ‘Newcastle Rose’ stood for, but he said, ‘It divvn't matter, like. It looks canny. The lasses will gan mad for it.’

Around this time the accent, dialect and earthy humour of the North East had also begun to pervade wider popular culture in the UK. There was the highly successful television series, ‘Auf Wiedersehen, Pet’, the widely read ‘Viz’ comic, the volcanic rise of the footballer, Paul Gascoigne, and, of course, the ubiquitous and inimitable Newcastle Brown Ale. The lads told me, stony-faced, that there was actually a wing in Newcastle General Hospital where men who were addicted to ‘Newkie Brown’ received treatment, and I believed them.

They never told me about Tish Murtha from Elswick though. If she wasn’t on the telly with Terry Wogan, or in a band on Top of the Pops, or running the 1500 metres at the Olympics, how would they have known about her? How would they have known that she was a photographer, or that her work mattered, or that she was even alive? How would they have known that, in blazing black and white, she was documenting and dignifying dead-end lives like ours on a council estate which was just as dark and derelict as this one?

Glenn and Paul on the Washing Line, Youth Unemployment (1981) © Ella Murtha

'[O]ne has only to look at football grounds to see how the evils of extreme right-wing groups are being preached to youngsters who seek some diversion from the misery of unemployment.' – Mr Robert Brown, Labour MP for Newcastle upon Tyne West, House of Commons Debate, ‘Redundancy Fund Bill’ (Feb 1981)

Flats with their windows all boarded up; the bus stop smashed to smithereens; the burnt out car at the back of Spar; the drunk uncle who staggered home from the social club on a Sunday afternoon; the stepdad who combed margarine into his hair because he couldn’t afford Brylcreem; the kids on the bottom estate who set fires in the park and danced in the ashes; the majorettes who twirled their maces and tossed them up higher than houses; the girls who pushed prams down the road as if they were ploughing a field; the mum of three who answered the door wearing sunglasses because she had two black eyes.

Sng’s documentary highlights that the main reason why people knew nothing about Tish Murtha and her photography was because she never received any financial support from the dead-eyed decision-makers who work for opaque, undemocratic organisations like Arts Council England.

Why would she? This country’s establishment doesn’t understand, doesn’t respect and doesn’t care about working-class culture, its narratives, artefacts, experiences or its history. It never has and it never will. Working-class creatives are regarded as unsophisticated, untrustworthy, unruly and, much more importantly, unconnected. Butchers, bakers and candlestick makers gripping onto cheap, borrowed or stolen pens, paints and plectrums.

Kids on Spare Ground, Youth Unemployment (1981) © Ella Murtha

‘On the whole, reports Tish [Murtha], the only generation who understand these youngsters are pensioners, perhaps because they remember the Depression years.’ - Blakelaw School’s ‘Roundabout Journal’ (1981)

Tish got used to this kind of letter:

‘Many thanks for your recent application for funding. We regret to inform you that your project proposal has been unsuccessful on this occasion. If you would like more specific feedback …’

And so you either fund yourself or you just give up.

Twenty years ago I was able to choose the former because I’d secured a job as a lecturer in film and cultural studies at a college in Manchester. Out of my salary I self-funded, self-distributed and self-promoted numerous campaign and charity promos, music videos for struggling acts, an international short documentary and two documentary features. All of which received absolutely no financial assistance, exhibition or promotional support from publicly-funded entities like the British Film Institute, Film Hub North or HOME cinema.

In turn, my debut working-class feature film, ‘Nobody Loves You and You Don’t Deserve to Exist’, was part-funded by my redundancy money between 2016 and 2022, and the rest was paid for by loans, credit cards and an overdraft which I couldn’t afford.

Each year students used to ask me:

‘How do you find the time to make all these films when you’re teaching us as well?’ And I’d reply, ‘It’s easy: never get married, never have kids, never get a mortgage, never own a car and never go on holiday. See? There’s plenty of time.’

‘That’s well sad, Brett. Why won’t the government fund you? Or the council?’

‘Because they don’t fund people like me, and I haven’t got the time to play their silly games.’

And you don’t have to take my word on this either. Following her time at the influential Side Gallery in Newcastle, Tish Murtha wrote a letter to Dennis Birkwood, her college tutor at Newcastle College of Arts and Technology, which Maxine Peake also narrates in the documentary:

‘I left the Side Gallery for a number of reasons, but mainly because of their peculiar attitude to me and my work – they wanted to manipulate it to fit their group philosophy … And the boss’ girlfriend was getting really spiteful and bitchy towards us, damaging expensive photographic work … ‘accidentally on purpose’. So, as they obviously thought it was all a big joke, and I should be grateful for any situation they offered, I told them all where to stick their job and what an offensive, incestuous little clique they were.’

In 2013 an exhausted Tish Murtha had to die from a brain aneurysm while on the dole for her photography to be finally recognised by national and international cultural commentators for what it is – the work of a major 20th century artist.

Karen on Overturned Chair, Youth Unemployment (1981) © Ella Murtha

Tish Murtha took a number of photographs of Karen Lafferty which appear in the 'Youth Unemployment' series. This particular image, which Tish would playfully refer to as 'Saturday night out on the dole', is currently a part of a collection at the National Portrait Gallery.

Her gloriously grim visions of broken buildings, broken people and broken Britain were ignored by the mainstream during her lifetime because they revealed truths about this country that simply made the authorities uneasy, but not ashamed: the inequality, the hypocrisy and the cruelty.

Of course, the self-entitled and self-serving right-wing establishment which the UK is cursed with relies upon, and revels in, keeping working-class culture in its place, down in its oubliette, year after year, decade after decade. At the very least it reminds the rest of the population of what to expect if they too decide to step out of line and speak up. What is more chilling however is that, while protected and empowered by the ideological and repressive state apparatus surrounding them, this establishment’s key historical figures have the experience, resources, personnel and desire to continue this war of attrition until the very end of time.

It is their country after all. For example, only just this week the official portrait of King Charles III was unveiled and, in turn, an £8 million scheme was announced by the Tory Cabinet Office to permit schools, police stations, hospitals and councils to request a free A3-size, oak-framed copy to hang wherever they see fit.

£8 million! Following her death, aged 57, Tish Murtha received a £100 rebate from her energy company.

She wasn’t a working-class photographer. She was a war photographer.

Kids Jumping on to Mattresses, Youth Unemployment (1981) © Ella Murtha

With Mark Murtha, one of Tish's brothers, holding on to a ventriloquist dummy (bottom left), this photograph now features in an exhibition at Tate Britain. As her daughter, Ella Murtha, tells us in the documentary: 'To actually say that Tate Britain has acquired me mam's work for a permanent collection ... The whole thought of that is just quite overwhelming really.'

***

Paul Sng’s documentary ‘Tish’ (2023), which chronicles the life and times of the late North East photographer, Patricia Murtha, is currently screening at selected cinemas across the UK, and is available internationally via the Curzon Home Cinema website.

Please also visit www.tishmurtha.co.uk, which is run by her daughter, Ella Murtha, for further information about her exceptional mother. Thanks to Ella for permission to use Tish's photographs.

Thanks also for additional research for this review, by Jack Clarke / @ClarkeJ98