Poverty, Class and Education: A report from the Alliance of Working-Class Academics' Conference, 2024

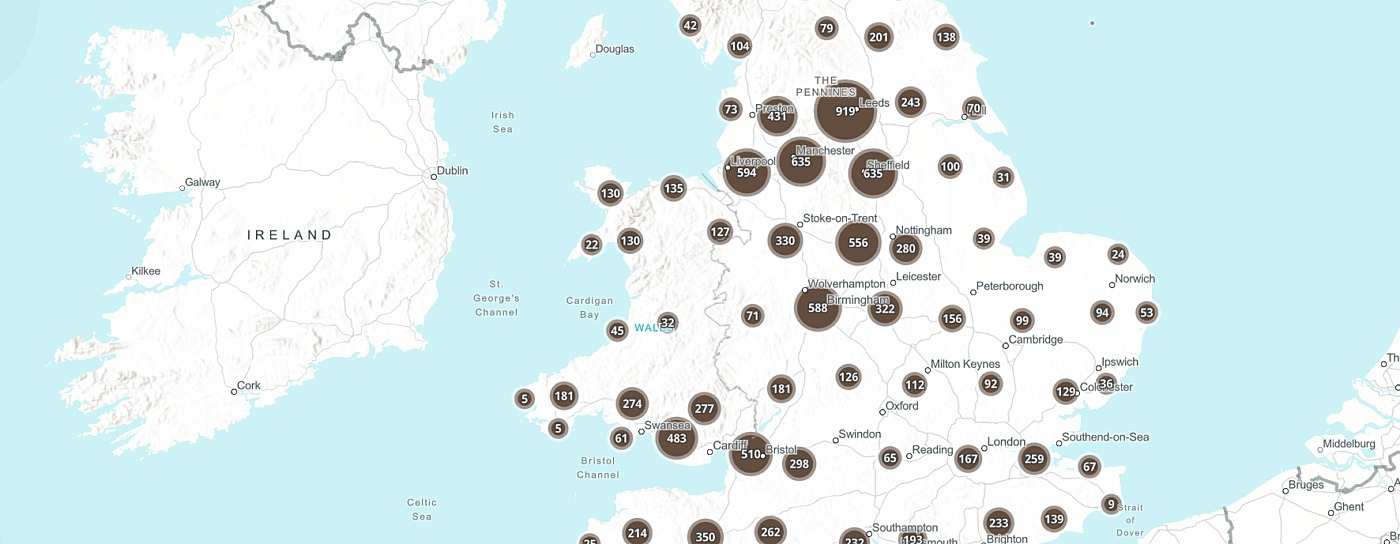

Image above: People take turns to do the difficult jobs, by Chad McCail

The 3rd annual conference of the Alliance of Working-Class Academics (AWCA), in conjunction with The Scottish Poverty and Inequality Research Unit (SPIRU), was held at Glasgow Caledonian University on June 14th 2024.

Amidst the UK’s increasingly divisive and deadening economic and political climate, the overarching aims of the AWCA are to be admired and applauded. They are:

1) Help academic colleagues overcome class-based barriers throughout their careers

2) Amass data on the economic, social, and cultural challenges facing working-class academics

3) Mentor and support working-class students

4) Develop best practices on recruiting, retaining, and meaningfully advocating on behalf of working-class faculty, staff, and students

5) Abolish global class discrimination.

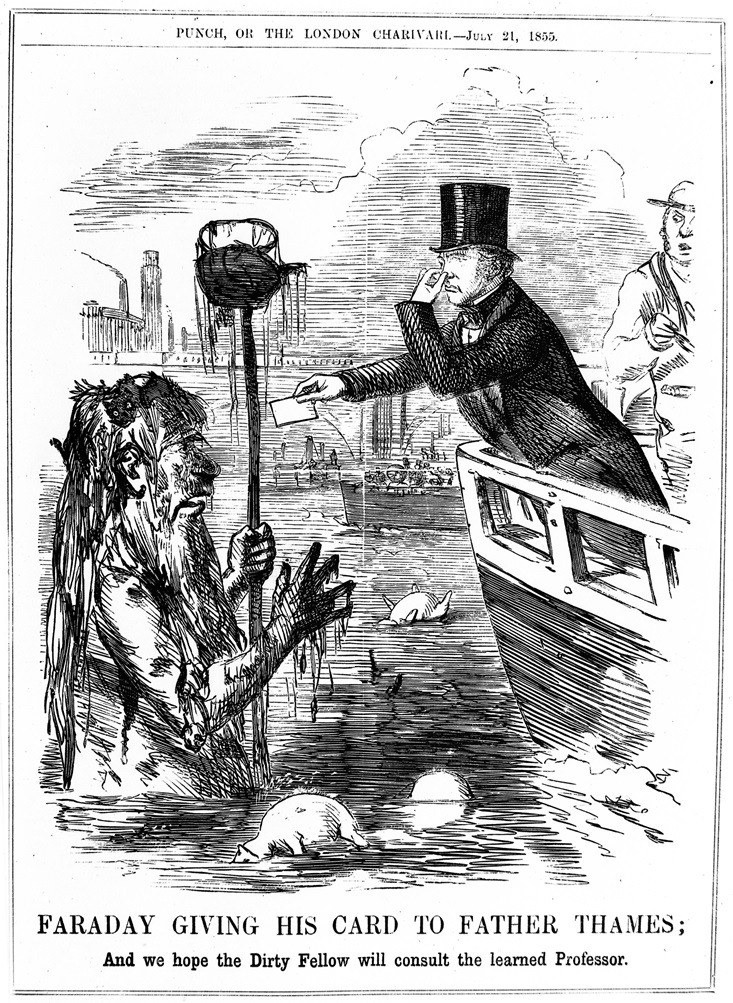

The focus this year was ‘Poverty, Class and Education – Conversations and Topics’ with specific attention being paid to working-class students in further or higher education who are suffering from low attendance, exclusion, isolation, alienation, mental health issues and high drop-out rates. Unthinkably, these are all typical features of the UK’s corporate education system in the 21st century which, it could be argued, are primarily ignited and fuelled by classism, inequality and poverty on an individual level, and by chronic underfunding and mismanagement at an institutional level.

The free-of-charge hybrid conference was attended by hundreds of lecturers, teachers, students and writers, alongside curious and concerned members of the general public. In turn, dozens of academics, researchers and practitioners from an extensive range of disciplines in education and the public sector presented an array of insightful papers. Characterised by in-depth experience, cutting-edge perspectives and imbued with a strong sense of moral duty, they examined in detail the routes, challenges and barriers which working-class students encounter before, during and after their journey through the institutional education system.

This education lark is not for me

Dr. Neil Speirs from the University of Edinburgh, for instance, put forward a paper entitled ‘Rejecting the Coldness of the Hidden Curriculum Through Loving Acts of Solidarity’, accentuating that at the core of higher education there is a clash between Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of ‘field’ (for instance, the values and practices of a working-class background) and ‘habitus’ (the values and practices of a middle-class university). This habitus is often embedded in the ‘hidden curriculum’, a method of situating, timing, resourcing and delivering lessons or lectures which prioritises and legitimises bourgeois understanding, expectations and ideals, i.e. a particular way of being.

In turn, this then facilitates a specific construction of knowledge and behaviour which can then only lead to compliance with the dominant ideologies that existed in the past, and that still exist now. That is to say, ‘Do as you’re told, stop complaining and you’ll get your degree’. This can pressurise working-class students towards a divided habitus, a form of cognitive dissonance, which can result in detrimental consequences for their learning experience, academic progress and employment opportunities. Such students often recount impressions like ‘I’m not taken seriously in lessons’, ‘The lecturer clearly doesn’t like me’, and/or ‘I don’t think this education lark is for me’.

Education is never neutral, but instead always serves certain socio-cultural interests while impeding others. As a remedy to the reproduction of working-class jobs for working-class kids, and middle-class careers for middle-class children, Speirs considered Paulo Freire’s pedagogy of ‘hope and love’. This negates and rejects the coldness of the hidden curriculum, its unfairness and inequalities, by identifying, revealing, challenging and rejecting its veiled discriminatory narratives and performances.

In response, educators should actively proffer ‘loving acts of solidarity’ and ‘compassion’ in order to begin to eradicate the dissatisfaction, frustration and alienation which working-class students frequently experience, as well as their disenchanting attendance figures and disproportionate drop-out rates.

Of course, one major practical problem in the UK is that the time, energy, and commitment which would be required to adopt and consistently implement such a humanistic approach would be completely unrecognised and unrewarded by university management teams, distracted as they are by the sanctity of their Excel spreadsheets and the nobility of their neoliberalist liturgies. However, quoting Dr Alpesh Maisuria, Speirs contends: ‘Only people working in solidarity can make history’.

A sense of shame and a code of silence

Easier said than done, as Dr. Pamela Graham from Northumbria University explored in her presentation, ‘Trying to Juggle Study and Work: University staff reflections on supporting students experiencing financial hardship’. Here Graham analysed how material issues like the cost of accommodation, food, heating and travel can force students into excessive employment hours outside of education and which can then lead to psychosocial and behavioural issues.

Stress, fatigue, poor attention span, irritability, lack of group integration etc. can thus impact their course achievements, attendance and retention. This ‘real world’ struggle for such students – who may also be unable to stay awake in lectures, afford a key text for a particular module, or even buy the latest clothing items – can be then exacerbated by a sense of shame and a code of silence due to the stigmatisation of financial hardship amongst the wider student body.

For example, I taught an Access to HE student in 2018 who also worked nearly full-time for the gambling company, Ladbrokes Coral. He would wear the same tracksuit to lessons, sit alone in the corner, yawn constantly throughout, sigh audibly whenever an academic task was set, only to then angrily disappear for two weeks to carry out extra shifts at the bookies.

As Graham reminded us, working-class students often opt out of valuable work placements and extra-curricular activities due to the costs and time involved, thus placing their cultural capital into unmanageable debt. Moreover, they also have to contend with a pernicious prerequisite which has burrowed its way into the UK’s psyche: that individuals from a working-class background who choose to formally educate themselves are somehow traitorous, and are thus meant to personally struggle and suffer in order to succeed; to escape the defeatist demands of their part-time job in the service industries, and the perpetual petty criticisms of their working-class peers at the pub, the club, and the kebab house; to try and better their own lives once and for all, as well as those of their children who are yet to be born.

Robbing a bank and founding a bank

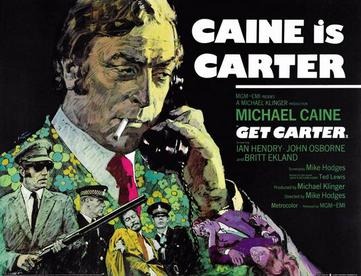

Just as memorably, Deirdre O’Neill from the University of Hertfordshire submitted an original and worthy initiative called ‘The Inside Film project: Radical Pedagogy, Prison and Class’ which focuses on short films produced by prisoners, ex-prisoners, and probationers who are almost exclusively poor and working-class. They are provided with filming equipment, and then attend workshops where they are taught the basics of camera operation, sound recording, scripting, storyboarding, and editing, alongside representations of class and race.

Understandably, most of the participants are already media-savvy from years of consuming news reports, soap operas, commercials, movies and music videos, and so are familiar with the conventions of film and media language. This critical space, however, also taps into their potential to address the profoundly political role which the mainstream media plays in constructing societal beliefs, norms and values that, more often than not, cast the poor as antagonists, background characters, or simply ‘scenery’, if they are ever cast at all. Crucially, the initiative – as a form of intellectual and creative activism – doesn’t speak on behalf of, or over, the participants, but provides them with their own voice, agency and legitimacy.

Facilitating personal and group creativity, this radical pedagogical approach provides opportunities for learners to understand and engage with the wider socio-economic and politico-legal context of their ‘crimes’. It transforms working-class experience into cultural consciousness in order to raise awareness about the class-based inequalities that are often responsible for the ‘deviancies’ of the marginalised and excluded. Interestingly, the films produced frequently focus on issues of justice and injustice, and can be seen in a way to echo Bertolt Brecht’s observation in The Threepenny Opera (1928): ‘What is the robbing of a bank compared to the founding of a bank?’

This wounded world of ours

Of course, due to the high number of sessions at this year’s very thoughtful and very human AWCA conference, it was not possible to attend and cover everything; it is hoped however that an edited collection of submitted papers will be assembled and published. Furthermore, while the focus was predominantly on Scotland and the UK, the overseas experience was rightfully considered in, for instance, ‘First Nation access to higher education in Australia’ by Dr. Emma-Jaye Gavin from Federation University.

Here, Gavin, a Garrwa Aboriginal woman from the Northern Territory, revealed the obscene statistic that, due to barriers of classism, racism and colonialism, not only did it take until 1966 to award a degree to a First Nation student, in today’s Australia First Nation people are more likely to go to prison than university. Indeed, she went on to explain that the Oceanic arm of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire continues to perpetuate scurrilous indigenous stereotypes. In response, she outlines the following solutions: more financial support from academia and the government; outreach projects in high schools; ongoing support for decolonisation projects and anti-racist pedagogy; as well as more role models to help redirect the negativity surrounding First Nation family discourse about formal education.

In conclusion, it has long been recognised that the education system is central to the cultural and economic reproduction of wider social division. Higher education is typically unwelcoming and hostile to working-class entrants, whereas the privileged who are able to navigate its middle-class habitus – its codes, culture, behaviour, and language – are often mistaken for having ability, are rewarded, and thus progress.

This year’s Alliance of Working-Class Academics' Conference reminds us that there are many, many intelligent, insightful and intrepid individuals who are working day in and day out to redress the scales of injustice, to encourage this class-divided, wounded world of ours to become a far more sensible, safe and successful place.