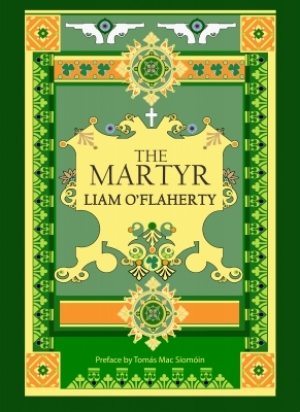

The Martyr: the last of Liam O’Flaherty’s banned novels to see the light in Ireland

Jenny Farrell introduce Liam O’Flaherty's The Martyr, Nuascéalta 2020.

Liam O’Flaherty’s banned novel The Martyr has just been republished by Nuascéalta, eighty-seven years since its first and only edition in 1933.

With this sensational republication of The Martyr, Nuascéalta publishers complete their epic task of restoring the remaining three major O’Flaherty novels on the index of the Irish state. The other two novels reprinted by them were the first book to be banned under the Censorship of Publications act, the Galway novel The House of Gold, and O’Flaherty’s insightful and scathing Hollywood satire Hollywood Cemetery. This publication makes available, for the first time since the 1930s, the entirety of Liam O’Flaherty’s novelistic work and moves towards a restoration of a panorama of this author’s work for a global audience.

Banned writings were dangerous to come by for many decades, and the long-term effect of such an establishment ban on literary works radiates to this day, as once censored novels can still be rare on library and bookshop shelves. O’Flaherty’s novels, mainly written in the 1920s and 30s, address significant events in Irish history and the newly emerging Free State. He was the first Irish artist to seriously confront the realities of the Famine and he wrote the important anti-war novel Return of the Brute. He examined the emergence of a fundamentalist Catholic State his books were banned and a whole people systematically kept in ignorance by a state betraying the ideals of independence.

Nuascéalta’s return of The Martyr to the reading public comes at a time when we commemorate – controversially – the centenary of the War of Independence and the Civil War. The Martyr gives O’Flaherty’s take on the battle to control the country’s destiny. The novel, written just ten years after the Civil War, brings to life the nationwide Free State attack on the anti-Treaty forces. One such offensive was the landing at Fenit in Kerry. Liam O’Flaherty fictionalises this incident at “Carra Point” and “Sallytown” (Tralee). Events around the Free State troop landing and its sequel are seen through the eyes of Sallytown’s defenders and its townspeople, clerical and lay. In the author’s imaginative reconstruction, professional Free State troops face Sallytown’s ill-trained, badly led and poorly equipped volunteer defenders.

O’Flaherty’s point of view, here as in his other novels, is always informed by his understanding of class and class interests. He writes from the point of view of the ordinary people – fishermen, peasants, workers. As part of this perspective, he leaves no doubt on which side in the civil war the gombeen class stood:

Every one of these peasants felt that Tracy was fighting for Ireland and that Sheehan was not. Down in their souls they felt it, by instinct; … It was all very well for posh fellows in Dublin, he felt, to mock at these ignorant poor people; but all the same the poor people’s instincts were always right in the long run.

O’Flaherty presents the reader with the complexities of each class, as erstwhile comrades find themselves on the opposing sides of this tragic conflict: Sheehan

was about the same age as Tracy and he had an equally brilliant record as a guerrilla fighter. He came from a village on the coast of Cork and he had been a fisherman before he became a revolutionary. He had been admitted into the ranks of the Republican Brotherhood for a very skilful landing of some arms right under the eyes of a British gunboat.

This central conflict of the novel, that between Tracy and Sheehan, comments memorably on how differently the civil war could have ended: Sheehan refuses to kill Tracy and defies any military order to do so.

The group of revolutionaries around Tracy as their central player is diverse. Some, like Rourke are simply farmers, others like Crosbie are devout Christians, and others again have been soldiers, guerrilla fighters and imprisoned. There is also an informer among them.

The Martyr is a rare Irish Civil War novel that presents some fighters on the anti-Treaty side as informed by the socialism of Connolly, indeed declared atheists and communists, and Tracy and Sailor King have most in common with O’Flaherty’s own thinking. However, O’Flaherty combines all these diverse people into a group around Tracy to shape a group hero, as opposed to the idealised individual hero that dominates the bourgeois novel. This band of revolutionaries includes women, although there is a certain degree of stereotyping in these female characters, including the rather startling portrayal of Constance Markievicz.

Brian Crosbie, Sallytown’s ineffectual Republican leader, is also based partly on an historical character – Terence Mac Sweeney. Crosbie, who becomes the martyr after whom the novel is named, is central to the plot. Mac Sweeney was a deeply devout Catholic, who described Ireland’s struggle for independence as a religious crusade and his goal as a new Catholic state. Laid out in his coffin, he wore underneath his IRA uniform the rough brown habit of a Franciscan monk.

Crosbie’s ineffectuality arises from his Catholic nationalism, an issue of immediate relevance to O’Flaherty at the time he wrote the book. An extensive dialogue between Crosbie and his Free State army torturer Tyson, reminiscent of Satan and Christ in the desert, paves the way for the novel’s shocking ending.

This raw novel provides a gripping contemporary account of events that defined Irish history. It contradicts revisionist presentations of those times and suggests that, at a time when History is being removed from school curricula, one should read literature. It is unlikely to find favour among the descendants of the ‘Stater’ camp, and could make for an uncomfortable reminder for the modern offspring of the anti-Treaty movement. Following the recent general election, the media, along with the politicians of Fiana Fáil and Fine Gael, trumpeted about overcoming the divisions of the past, in an effort to exclude from government the party that aspires to achieve the goals of the anti-Treaty party of the Civil War. O’Flaherty reminds us of what this was all about.

The Martyr is available as an ebook from Amazon.