‘It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.’ Brett Gregory interviews Bram Gieben, author of ‘The Darkest Timeline: Living in a World with No Future’

Below is an edited version of the interview.

Brett: Hi. What’s your name, where do you live, and when, and why, did you first become interested in writing?

Bram: Hi, Brett, how you doing? My name is Bram. I live in Glasgow in Scotland. I'm originally from Edinburgh, that's where I grew up. I've been writing since probably a very young age. I was the 2015 Scottish Slam Champion and I've kept on performing and writing poetry for the stage and for the page since then.

Brett: And what specifically inspired you to begin writing this particular book, Bram?

Bram: I've always been interested in theories around dystopias and utopias. I've always been fascinated by stories about the apocalypse and the pre- and post-apocalypse films like Mad Max. I'm also a huge fan of Mark Fisher and even just his prose style, his approach to writing and structuring essays, that was very influential on me as a journalist. He was paraphrasing both Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek when he said ‘it's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’, and that leads into an analysis of some of the aesthetics of apocalypse fiction, and why those might not be the most useful frame through which to understand our dystopian present.

Brett: Due to my own Scottish roots I’ve always been drawn to the country’s great literary tradition of producing narratives that can be seen to be antagonistic, pessimistic, and even apocalyptic. As a writer who is based in Glasgow, is this a creative heritage which you feel consciously a part of and, if so, why? Is it the weather? The landscape? The economy? The politics? The history?

Bram: That's a good question. Why is Scottish fiction and storytelling apocalyptic? Oh, that that's a really good question. I didn't grow up in Glasgow actually. I mean, I was born in England to Scottish parents. My mum's from the Orkney Islands, my dad grew up in Aberdeen, but his family's originally part Dutch, hence the strange name. Scotland’s got its own very distinct social codes, it's got its very own distinct norms and traditions, and it's got its own incredibly rich history, and it's a rich and bloody history as well. You know, there's a strong argument that you could consider Scotland a colonized people although, you know, obviously that's been the case for so long now that that's very normalised. And there is a strong tradition of class consciousness and political consciousness in Scottish writing.

I think definitely, you know, Irvine Welsh's work is directly political, commenting on, you know, inequality, poverty, prejudice against people of working-class backgrounds or people with drug problems, you know? Ian Banks was a master of crafting science fiction novels which kind of dealt with the human condition, and where humanity might be headed among the stars, and deep philosophical issues about our, you know, in-built tendencies for violence, or even for empathy. So, yeah, I think it lends itself with its tendency to be rainy and gloomy, to maybe some dystopian speculation, you know, ruminating while the storm rages outside.

Brett: In your book you contend that evidence shows that ‘we do not truly care about other people — or rather, people we have ‘othered’. This could be countered however with the observation that millions upon millions of people actually don’t care for themselves either, physically, psychologically, emotionally and/or domestically.

Bram: You know, I think that often if you find yourself in an oppressive low, if you find yourself in a cycle of addiction, if you find yourself unable to escape a cycle of abuse, a lot of that has to do with, or is exacerbated by, a sense of shame, a sense of low self-worth, and a sense of not being able to picture a better world for oneself. And I think a lot of that shame comes from that same process of ‘othering’. You think , ‘Well, I'm not like a normal person. I'm not like a good person. I can't get out of here.’ I mean, I'm just drawing on my own experiences there, my limited experiences with addiction, my kind of extensive experience of suffering from bipolar disorder, going through treatment for other mental health problems.

So, I don't know, I mean I'm somebody who has a regime of self-care, self-analysis, you know? I go to therapy, I exercise and meditate. Those are all things that I have had to learn to do out of necessity to care for myself. Otherwise I would have been, I don't know, dead in jail. All I would say is that for me my recovery has massively involved learning to love structure. I have a very structured life, I structure it for myself, I try and keep busy. I exercise, and I try and eat as healthy as possible – don't always manage it!

Brett: You quote the anthropologist, Jason Hickel: ‘[I]t seems all too clear: our economic system is incompatible with life on this planet.’ However, you also reject the speculative communist solutions put forward by the Swedish author, Andreas Malm. That is, you write: 'By the time we have regulated and campaigned our way to Malm’s functional communist society, everyone will be dead'. What should we do then?

Bram: I think the urgency of the apocalyptic messaging that we've had on climate change and other things for so many years has been quite intense. I think the problem with some of that messaging for me at least has, in fact, been its emphasis that we can do something you know from cycling schemes to, you know, carbon credits, carbon offsetting schemes like that. All of these things seem to me to be very much like distractions that capitalism has come up with to kind of, you know, convince us that something's being done when, in actual fact, the problem isn't being addressed. And I think really if you look at the big polluters those are nearly all corporations and, you know, even if all of the nations of the world reduce the output from people's homes, the output from industry, it's the output from agriculture that really contributes to climate change.

So really, on a fundamental level, there is nothing that we can do to fix climate change, I believe at least, without transforming or getting rid of capitalism in quite a radical way. We've known about the problems of particularly climate collapse, you know, and threats to ecosystems, problems with extracting fossil fuels; we've known about that since the 1960s, that was the time for concerted political action and, in an actual fact, like if humanity had taken collective action at that point we could probably have mitigated a lot of the effects of it. And that really was the ambition of my book: not to propose a different system or, like Andreas Malm does, not to propose necessarily any different solutions, but rather just to draw attention to the ways in which we're not talking about the problems in a very useful way.

Brett: Of course, we can condemn the self-centred, capitalist lifestyle choices of ordinary citizens on the ground, even when they delude themselves into thinking that they’re helping to reverse climate change by recycling regularly and buying fair trade tea bags. However, shouldn’t it be our leaders in politics, business, industry, science etc. who should be publicly and permanently held to account for their myopic, self-serving decision-making, ideally with real-world legal consequences which their peers will genuinely heed and fear?

Bram: You know, no matter how virtuous you are in one area, there's probably something else that you're doing that's harming the planet and, you know, you can you can try and live like an absolute saint but, nonetheless, you still have a carbon footprint. There's a thing called the Five Earths Argument. I mean, basically, what that says is that if everybody in the developing world was able to access, you know, the kind of consumer goods, fast food and all that stuff that we have available to us in the West, we would need the resources of five earths to feed everybody.

As to your point about should it be leaders in politics, business, industry, science who should be publicly held to account, I definitely do think that they should be. I think the likelihood of them being held to account is probably pretty low. You only have to look at things like the investigation into the Post Office Scandal to see how slippery those six figure salary senior executives can be when you put them on the spot. Things like public inquiries can become a ritual: they're meant to reassure us that something is being done, heads are going to roll. Meanwhile, in the background, the next scandal is probably brewing under the same kind of secretive management cultures. Our rights as people in this country to protest are under threat, rights to free speech and freedom of association are under threat. If you don't have power and you want to see change, you have to take power in whatever form that you can.

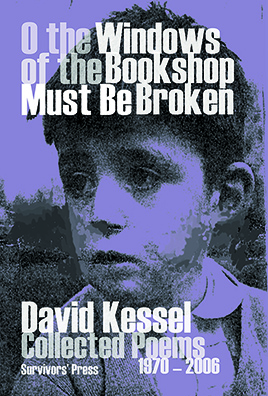

‘The Darkest Timeline: Living in a World with No Future’ is published on June 24th 2024, and is available to pre-order now on the Revol Press website.