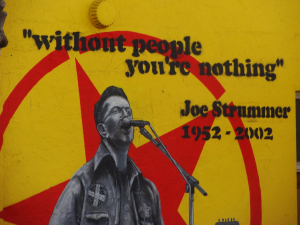

Radicalism, resistance and rebellion: The punk rock politics of Joe Strummer

Joe Strummer, leader, lead singer and lyricist for the seminal punk band, The Clash, died twenty years ago this year. But long after his death and that of The Clash in 1986, he continues to exert a considerable influence upon the education of innumerable individuals, propelling them towards adopting and maintaining radical, left-wing politics.

Alongside the musicianship of Mick Jones, Strummer was able to provide passionate live performances which elevated the influences of his lyrics into political epiphanies for many. Amongst them are many union leaders in Britain today like Matt Wrack of the Fire Brigades Union.

This is the central conclusion from my research for my new book, The punk rock politics of Joe Strummer: Radicalism, resistance and rebellion. The research for it was based upon taking testimony from over 100 individuals of different ages, genders, generations, countries and continents. What lessons can the left learn from Strummer for putting across its radical message?

The main one is that people, especially young people, are 'into' music in a way that is not true of other art forms like films, poetry or sculpture. Music can provide a stronger and sharper psychological connection with the listener, bringing about strong emotional feelings. For that reason, it is the clear candidate to be the primary form of culture that needs to be used to convey left-wing ideas. This is not instead of writings, whether books or pamphlets. Rather, it is a way of stimulating the desire to approach them, having had an enjoyable emotional experience which is in a bite-size digestible form.

Examples of Strummer doing this are most obviously found in his songs ‘Spanish Bombs’ from London Calling (1979) about the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939 and ‘Washington Bullets’ from Sandinista! (1980) about American imperialism in central and south America. In the former, he wrote:

The shooting sites in the days of '39 /…/ The freedom fighters died upon the hill / They sang the red flag / They wore the black one /…/ The hillsides ring with "Free the people" / Or can I hear the echo from the days of '39? / With trenches full of poets/The ragged army, fixin' bayonets to fight the other line.....

while in the latter:

As every cell in Chile will tell / The cries of the tortured men/Remember Allende, and the days before, / Before the army came/Please remember Victor Jara /…/ When they had a revolution in Nicaragua / There was no interference from America /…/ Well the people fought the leader / And up he flew / With no Washington bullets what else could he do?

See Youtube clip here (it's only available to watch on YT).

In a pre-internet age, such songs sent many scurrying to their local library to find out more. Nowadays, there are websites explaining his lyrics and links to further written, audio and visual materials.

So, Strummer gave us a 'masterclass' in the way to converse with an audience, whether it be over environmental destruction, what we now call neo-liberalism, of fighting racism and fascism. Though he seldom was explicit about what listeners should then do, he was always clear that some form of activism was necessary to make good on the ideas.

Of course, his charisma and self-confidence as well as having the platform of punk were all critical in his ability to widen the appeal of being such a wonderful wordsmith. The only other lyricist that comes close to Strummer in giving a radical worldview mass appeal is Paul Weller in the closing period of his first band, The Jam, and in his next band, The Style Council.

What does this practically mean for the left? Over and above being able to analyse the progressive political nature of cultural artefacts like a song and promote those groups and bands which are in their songs radical in challenging the status quo, the left needs to take a big step.

It needs to consciously create its own music. This means left organisations creating the infrastructure and opportunities for their members and supporters to produce music which has a radical intent. The costs and difficulties of producing and distributing music today are so much lower than back in Strummer’s day. Sure, the lyrics will have to be clever and well-crafted and the instrumentation and arrangements appealing. But there is then a chance for the left to use this means to speak to a much wider audience than it has been able to up to now. Songs can be an introduction not only to tomes on capitalism, imperialism and neo-liberalism but also on what to do about them. As Strummer said in ‘Working for the Clampdown’ (1979): ‘Kick over the wall 'cause governments to fall. How can you refuse it? Let fury have the hour, anger can be power. Do you know that you can use it?’