'Capitalism: A Horror Story': An interview with the author

Brett Gregory interviews Jon Greenaway, author of 'Capitalism: A Horror Story'

BG: Hi, my name’s Brett Gregory, and I’m an associate editor of the UK arts, culture, and politics website, Culture Matters. I’ve interviewed 19 authors, artists, and academics over the past year and a half, and today will be my 20th guest, the writer of a new political book called ‘Capitalism: A Horror Story’.

BG: Hi, what’s your name, where do you work, and what are your research specialisms?

JG: Hi. Thank you so much. My name is Jon Greenaway. I'm currently an independent writer and researcher, and I specialise in Gothic Studies, Horror Studies, film, and Utopian Theory.

BG: Let’s start at the beginning. With examples from film and/or literature, how would you define Gothic horror in terms of style, content, and conventions?

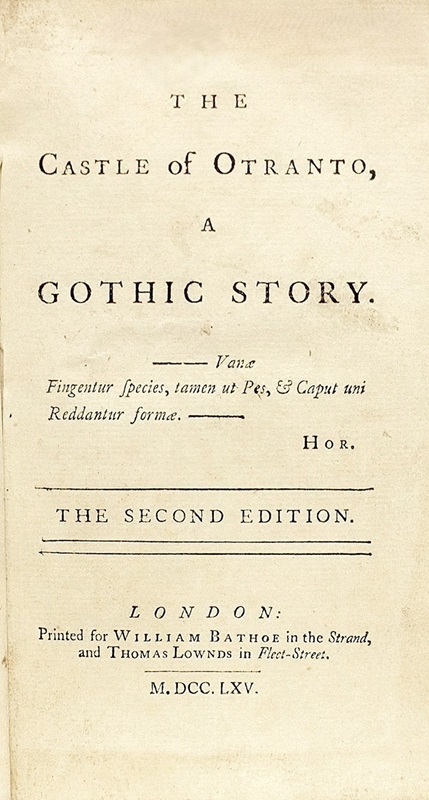

JG: To define Gothic horror in terms of its style, content and conventions is something that involves going back probably to the late 1700s. Generally, Sir Horace Walpole's ‘The Castle of Otranto’ which was published in 1764 is counted as being the sort of first true Gothic novel, and inaugurating a particular set of concerns and ideas. Most of these revolved around history, haunting, the supernatural. So to talk about the Gothic is one thing, but to talk about horror is another aspect to this genealogy. So a lot of the Gothic emerges from these aesthetic debates around literature more generally, particularly Edmund Burke's aesthetics and theory around sublimity, what the sublime is in literature. And the distinction that's generally drawn historically is that the Gothic is something that draws you to towards the sublime, it is an expansive feeling of awe, whereas horror is something that we recoil from.

BG: And how would you define Gothic Marxism in terms of ideological aims, objectives, and historical background?

JG: In terms of Gothic Marxism, in terms of its ideological aims, objectives and historical background, there are a number of different kind of genealogies or traditions that I think you can draw from. I think one of the most underappreciated, but probably one of the most important, is a two-fold tradition that emerges out of French surrealism on the one hand, and the aesthetic and philosophical work of Walter Benjamin on the other, and both of them are interested in doing similar things.

So Benjamin's work, particularly something like the great ruin of a book, ‘The Arcades Project’, is an attempt to investigate the fundamentally unfinished nature of history, and to try and give history itself a sort of dynamic, living charge. The surrealists are trying to do the same, but for the repressed or unconscious aspects of culture. Basically, at a sort of super foundational level, I would say that to have a Gothic Marxist account of culture is to take seriously the idea that history is not finished, that there are aspects of culture which are not simple irrationalisms that we have to get over or move on from. But these unfinished haunting or non-rational aspects of culture have deeply revealing things to tell us and teach us about history, the nature of politics, and the nature of subjectivity.

BG: With this in mind you write extensively about Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’ published in 1818 and, in particular, The Creature who has been ‘stitched together from the bodies of the poor and the dead’. While this is an extremely evocative indictment of capitalism’s corporeal exploitation of the proletariat and the precariat, you argue that it’s The Creature’s often overlooked sentience in the novel, their articulation, their reading of Plutarch and Milton, which is their true subversive power. Would you care to explain this further?

JG: ‘Frankenstein’ is a really interesting novel, and it's far stranger than I think people who maybe haven't read it for a while think. One of my favourite things about Frankenstein's Creature – and I try to refer to The Creature rather than a Monster from the novel – is that The Creature, the great horror for Victor Frankenstein is that his creation can speak, his creation can reason, and there are these moving passages where The Creature recounts their own coming to self-consciousness.

You know, they do read Volney, they do read Plutarch and Milton, and have a rational and philosophical approach to their own consciousness. The great horror for Victor Frankenstein is that his Creature speaks in the same discourses that he sees himself as having exclusive access to. The Creature is reasonable, he makes an appeal to Frankenstein as if Frankenstein is a judge in a court of law, and the response of Victor to this very impassioned defence of reasoned debate is violence.

BG: Interestingly, The Creature, particularly in the movie adaptations, is also superhuman and, we later discover, unable to die. If I remember correctly, you equate this characteristic with the notion that the poor in society and culture will never die either and will continue to haunt capitalism and its dead-eyed, deluded disciples until the end of days.

JG: The characterisation of The Creature in the novel with the notion that the poor in society and culture will never die either, and will continue to haunt capitalism until the end of days. I think this is a nice way of thinking about it. If you think to the very end of the novel The Creature vanishes out of a window and is lost in the darkness, but is never completely eradicated. And I think there are so many ways that we can see the figure of Frankenstein's Creature as this very powerful, multivalent metaphor, yes, for the continued existence of the working class, no matter how marginalised and excluded they might become. But also The Creature has a revolutionary and disruptive potential in the course of the novel, so I think you're completely right, and I would totally agree with your argument, but I would also say that perhaps there is a more hopeful way of reading this that, yes, despite the apparent security of Victor Frankenstein, that great representative of the bourgeois middle classes on the edge of things, one that is completely on the edge of things there remains this kind of haunting figure of a revolutionary class.

BG: You proceed to analyse Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ published in 1897, another incredibly influential icon from the Gothic genre, although, on the surface, they don’t enjoy a similar affiliation with the exploited proletariat which Victor Frankenstein’s creation does. That is to say, many of us would regard Count Dracula as being the aristocratic embodiment of early 20th century capitalism, feeding off the poor and the innocent to sate his own nefarious desires in order to expand his dominion.

You understand them from a different perspective, however.

JG: Yeah, this is a really interesting chapter, I think. ‘Dracula’ is often read in this kind of as a figure of capitalist predation, and I think the reading is valid, but it raises some problems that you have to kind of ignore or gloss over certain parts of the text. Quite literally the novel is about a lawyer going to a foreign country to help a foreign investor buy property in London. However, I think that's not the sole way of reading the novel. I'm very indebted particularly to the sort of feminist critics like Katie Stone and Sophie Lewis who have talked about family abolition as a utopian programme, and there are a couple of things about Dracula that allow you to give this kind of counterintuitive reading to the novel.

So Dracula, of course, does not work, and is a threat to the extremely patriarchal and heterosexual family structures, the social structures of the London that he's moving into. There is a kind of troubling ambiguity, there is a troubling maternal side to Dracula who feeds Mina Harker from his breast, and kind of inducts her into a new family structure. And it's very telling that it's a group of men then that have to secure their sort of ownership of property, but also their own kind of like heterosexual neuroses has to be worked out in excluding Dracula. So Katie Stone who wrote this brilliant paper on Dracula as a utopian figure points out that he is representative of a sort of familial mode of connection that goes beyond work. The great horror of Dracula is that he doesn't need to accumulate capital, and he doesn't need to work for it like everyone else in the novel does. It's something that ‘Dracula’ as a novel manages to destabilize in some really interesting ways.

BG: Unashamedly, your book puts forward a utopian vision in terms of us finally accepting the monstrousness within our own histories, our own cultures, our own political systems, as well as within ourselves, in order to bring about positive change. Before this can occur on a large scale however, shouldn’t people first be guided and encouraged to fall in love with the subversive power of reading and learning before they venture on to the political battlefield of, say, the utopian imagination?

My rationale here is that since Gothicism is traditionally linked to Romanticism which, in turn, connotes ideas of aristocracy, high culture, and elitism, isn’t there a danger that so many who are either, for one reason or another, ill-read or uncultured, will be left behind? I’m thinking here, for example, of the workers who help to build the laptops, the writing desks and the office chairs upon which writers and academics research and compose their work.

JG: I really like, I really like this question because this is a very challenging question because it makes an excellent critique of Romanticism. And I would say that, yes, this book fits into what often gets called ‘Romantic Anti-Capitalism’. So ‘Romantic Anti-Capitalism’ was first coined by the Hungarian philosopher and communist, György Lukács, and Lukács thinks that ‘Romantic Anti-Capitalism’ is essentially irrational, and this is because it's tied up in as, exactly as you pointed out, these notions of high culture, of aristocracy, of the individual, but I would say that this is not the only mode of Romanticism that there is. There is also precisely this vision of mass of communalisation, of the commune of the mass over just the aristocrat ruling over us, and there is this idea of a kind of vision of life that embraces the complexity of the totality.

So, yes, I would agree there is this belief in the kind of subversive, as you put it, the subversive power of reading and learning, but I think this wildly underestimates just how popular the Gothic always was, traditionally. Right, so the 18th and 19th century, the great Samuel Taylor Coleridge referred to the Gothic novel as the trash of the circulating libraries, right? The stories of monsters were not simply for the aristocrat, and those who had their reading library at home, but monsters and the old Penny Dreadfuls, and the sensation fiction of the 19th century was beloved by an extremely literate and extremely poor group of readers. You would borrow your Gothic novels from the lending libraries rather than having to buy them for yourself, so many Gothic tales were first published as instalments in magazines and, yes, these were commercial enterprises, but they were read widely and massively by working-class people rather than some enlightened aristocrats sitting in an ivory tower.

So the workers who help to build the laptops to writing desks and the office chairs, is there a danger that that so many who are ill-read might be left behind? I think we should never underestimate the ways in which working-class people have educated themselves and told their own stories. I think the great thing about the Gothic and horror is that it speaks very immediately to these concerns in ways that are elusive and referential and metaphorical, but are very connected to immediate fears, concerns and anxieties around bodily autonomy and bodily integrity, and our human finitude and fragility. So, yes, there is an elitism to Romanticism, but there is a revolutionary spirit in it too, and it's in that spirit that ‘Capitalism: A Horror Story’ has been written.

BG: Many thanks for your time, insights and patience, Jon. It’s been an extremely illuminating discussion. ‘Capitalism: A Horror Story’ is a serious, and challenging book. Its narrative stretches beyond the aesthetic confines of literature and film, bleeding into the real world of politics and people, their presence, their passions, and their purpose. It is highly recommended, and is available here.

Here is an extended version of this interview...

Brett Gregory

Brett Gregory is an independent screenwriter, director and producer based in Manchester (UK).

Latest from Brett Gregory

- How to make a film: Brett Gregory spills the beans

- The Tenementals: ‘Songs of Protest: Scotland, Spain, and Santiago’

- ‘The UK’s Pretty Much Shattered!’: Interview with Mike Wayne, author of 'Marxism Goes to the Movies'

- AI in the Movies

- ‘It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.’ Brett Gregory interviews Bram Gieben, author of ‘The Darkest Timeline: Living in a World with No Future’