John Green outlines the role of film in the Bolshevik Revolution, and the profound and lasting influence of Russian revolutionary film-makers on cinema not only in the Soviet Union but across the world.

According to the Bolshevik government’s first Commissar for Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Lenin remarked that, ‘Film for us is the most important of the arts’. What is particularly significant in this position is that Lenin not only clearly recognised film as an art at a time when many still considered it merely a form of cheap entertainment, but that he also recognised, even at this early stage in its development that it would have a huge and influential future.

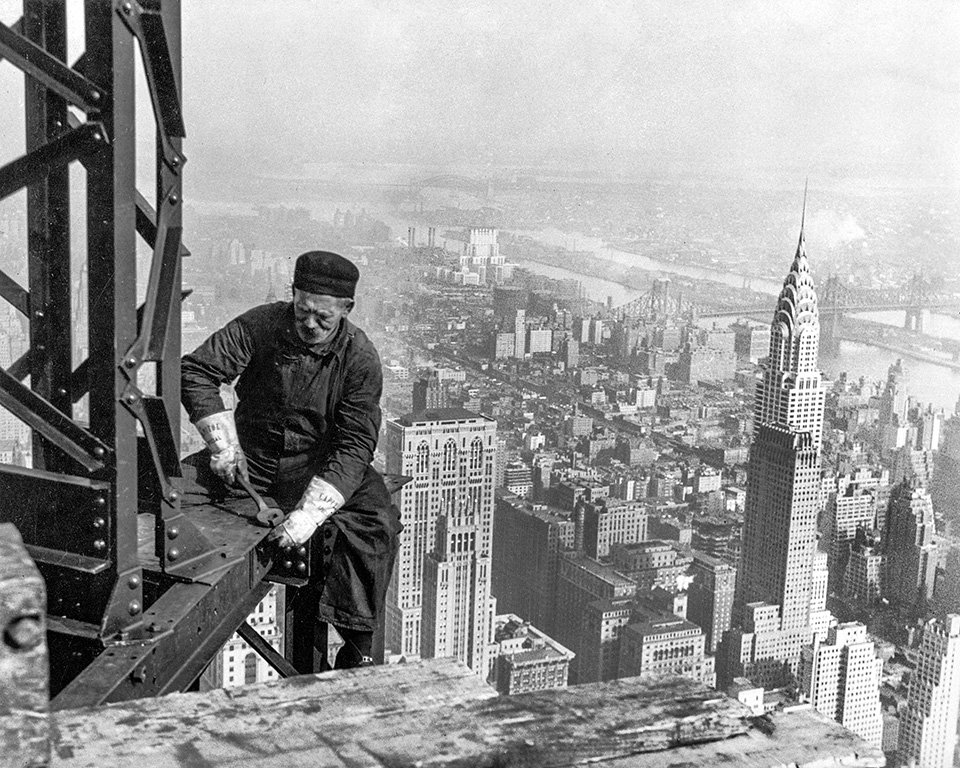

The young Soviet Union was faced with a large population made up of many nations and ethnicities. Overwhelming numbers were illiterate and the means of communication in the country were undeveloped. The Bolshevik leaders were faced with the daunting task of explaining the revolution to the people and galvanising their latent energies, but they didn’t have the luxury of time or tranquil conditions in order to do so. The promise of the new medium of film – at that time still only a silent medium and used as a fairground entertainment only – was recognized immediately by those with imagination and vision.

The possibilities of cinema as a propaganda, agitational and educational tool intrigued the Soviet leaders. Their fascination with new technology in general as a means of transforming a backward society probably contributed as well. Lenin dictated this note to the Commissariat of Education, which was responsible for the cinema, with a request that it draw up a programme of action based on his directives. In an early conversation that Lunacharsky, the first Commissar for Education, had with Lenin, he recalls that Lenin uttered his oft quoted statement ‘that of all the arts the most important for us is the cinema.’

A declaration was issued by the People’s Commissariat for Education on the organisation of film showings. A definite proportion should be fixed for every film-showing programme. And while it recognised that film is very much a medium of entertainment, in programming it insisted that there must be a strong educational and propaganda component.

The Commissariat for Education also stressed that films ‘From the life of peoples of all countries,’ should be screened in order that film-makers should have an incentive for producing new pictures. ‘Special attention should be given to organising film showings in the villages and in the East, where they are novelties and where our propaganda, therefore, will be all the more effective.’ (First published in Kinonedelia No. 4, 1925).

The new young Turks like Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Vsevolod, Pudovkin and Alexander Dovzhenko took up Lenin’s challenge with alacrity. The young film medium, based as it was on mechanical proficiency and industrial expertise, captured the interest of the new generation of communist artists who realised that the new society they wished to construct could only be built on the basis of rapid industrial development and technological innovation. These pioneers grasped this new ‘entertainment medium’ with both hands and transformed it into a powerful means of communication. These directors were inspired by Marxist theory and saw that they could apply Marxist ideas to the making of films, but each film-maker did so in their own individual way. Eisenstein was, though, the only one to elaborate an all-embracing Marxist theory of film-making. He put this into practice in his own film-making, in terms of selection of camera angle, juxtaposition of images during the editing process, movement within the frame and later in terms of sound and music also. For the first time the ideas of Marx and Marxist theory were applied to film-making.

Eisenstein

Eisenstein was undoubtedly the most influential of the new young Soviet film-makers – a trained architect, he took to film like a duck to water. Seeing far beyond the idea of moving pictures, he developed a whole new science of film-making based on Marxist dialectics. Eisenstein was a pioneer in the use of montage, a specific technique for film editing. He, alongside his colleague and contemporary, Lev Kuleshov, were two of the earliest film theorists to argue that montage was the very essence of cinema, and, used effectively, could enable us to see and comprehend a deeper reality. Eisenstein’s essays and books – particularly Film Form and The Film Sense – explain his theories of montage in detail and provide a theoretical grounding for future film-makers.

By using a unique form of montage i.e. how the individual celluloid takes were spliced together, he demonstrated that meaning could be created by juxtaposing images rather than, as had been done up till then, splicing them in simple chronological sequence. By placing one image (in Marxist terminology, the thesis) immediately next to a very different or ‘opposing’ image (the antithesis), a new concept (the synthesis) is created.

He saw editing as the key to a film’s impact. Film was for him much more than just a useful tool in expounding a scene through a linkage of related images. He felt the ‘collision’ of shots could be used to influence the emotions and consciousness of an audience and that film could achieve a metaphorical dimension. While making films, he developed a comprehensive theory that he termed, ‘methods of montage’.

His iconic film Battleship Potemkin is probably the most famous example of this approach, but Strike (1924) was his first film. It depicts life at a factory complex in Tsarist Russia and the conditions under which the workers laboured. The plot is centred on the workers organising a strike which in response to repression escalates into a full-blown occupation. Such a blunt depiction of ruling class repression had never before been visualised in this way. But what makes this and Eisenstein’s other films so special is that the audience is not allowed for a minute to remain passive, but is drawn into the struggle and becomes almost part of it. It is difficult to imagine today when you look at old grainy prints of Battleship Potemkin, that audiences were so stirred by its imagery that they swarmed out of the cinema determined to make their own revolution. The ruling classes were so frightened of it that its public showing was banned for many years almost everywhere outside the Soviet Union.

After the success of Strike (1924), Eisenstein was commissioned by the Soviet government to make a film commemorating the unsuccessful revolution of 1905. He chose to focus on the crew of the battleship Potemkin. Fed up with the extreme cruelties of their officers and their maggot-ridden meat rations, the sailors mutiny. This, in turn, sparks an abortive citizens' revolt on the mainland against the Tsarist regime. The film's centrepiece is the classic massacre on the Odessa Steps, in which the Tsar's Cossacks methodically shoot down innocent citizens. The image of a dying mother who lets go of the pram she is pushing, leaving it to career down the steps with the baby still in it, has become one of the most iconic and moving shots in the history of cinema.

He was the first cinematographer to develop a proper film language, one appropriate to the challenges facing the new Soviet republic. His best known films, Strike, Battleship Potemkin, October, Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible all bear testament to his contribution and the power of his imagery.

Many of his plans were, sadly never brought to fruition. During his unsuccessful sojourn in the USA, he proposed making a film of Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man and of Sutter’s Gold by Jack London but the ideas failed to impress Hollywood producers at the time and were vehemently opposed by anti-communist elements in the Hollywood hierarchy. The same happened with his proposal to film Theodor Dreiser’s American Tragedy. While there, though, he developed cordial relations with Charlie Chaplin who introduced him to the socialist writer Upton Sinclair. Their subsequent attempt to jointly produce a film in Mexico was also, in the end, unsuccessful although the footage they were able to shoot was later, posthumously, edited into the film, Que Viva Mexico.

With all this wasted effort, Eisenstein was getting itchy feet to return home, as the Soviet Film industry was, in the meantime, already experimenting with soundtracks on film. Also, in the wake of an increasing Stalinisation of the arts, his techniques and theories were coming under attack for ostensibly ‘ideological’ reasons and he was being accused of ‘formalism’ and he wished to counter such criticisms.

Back in the Soviet Union he embarked on his epic Alexander Nevsky with a musical soundtrack composed by Sergei Prokoviev. Unfortunately he died at the age of 50 so was unable to realise his mature potential. It is a moot point whether his specific cinematic language could have been adapted to a post-revolutionary period, and in a different historical context. But there is no doubt that his work has influenced numerous film-makers down the ages and still does.

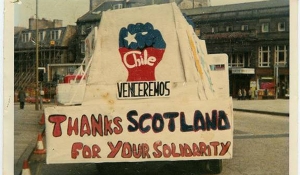

Soviet film-makers and their use of film inspired film-makers and cultural workers throughout the world. What characterised them, in contrast to their many colleagues in the West, was that they viewed film, in the first instance, as an educational medium. They were more interested in the use of film in its educational, propaganda and informative roles than as pure entertainment. and saw the medium primarily as a means of promoting human betterment and the promoting of socialist values.

The influence of Soviet cinema

The influence of Russian film-makers can be seen throughout the succeeding history of film. US classics like Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, with its adventurous camera angles, framing and editing would have been unthinkable without Russian cinema. The Italian Neo-realist wave leant heavily on its Russian forerunners. Directors like de Sica, Rossellini, Visconti and Rosi had all studied the way in which Soviet film-makers had been able to capture life on screen in a totally new, gripping and realistic way that superseded its former theatrical straitjacket. The films of the Hollywood greats like Billy Wilder, Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, William Wyler, Howard Hawks and so on all reveal the seminal influence of these early Soviet film-makers.

Early Soviet cinema ‘led the world, and laid much of the groundwork for the practice and theory of film for the 20th century,’ according to Annette Michelson, Professor of Cinema Studies at New York University. At a lecture she gave in December 2003, she and Naum Kleiman, Director of the Moscow Cinema Museum, discussed the ways in which Soviet and Russian film have interacted with the American film industry.

Kleiman pointed out that Russian émigrés like choreographer George Balanchine and actor Michael Chekhov, in addition to their influential roles in the world of dance and theatre, were active in Hollywood. As Michelson pointed out, Eisenstein never made a film in the US, after Paramount Pictures invited him to Hollywood in 1935, but the then never took on any of his projects. Nevertheless, she argues that Eisenstein's use of montage influenced American film, and is visible, she says, in such well-known scenes as the shower sequence in Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho. Hitchcock and other American directors re-interpreted montage usage.

According to Michelson, ‘In the hands of those Americans who admired Eisenstein's work, [montage] became a kind of tried-and-true conventional, visual, rhetorical device for indicating the passage of time, or the passage from one country to another.’

Kleiman underlined that many US filmmakers in the 1920s and 30s had seen and admired Eisenstein's films. He noted that in the 1970s, Francis Ford Coppola had told him that he had found artistic inspiration in October and Ivan the Terrible. Both Kleiman and Michelson felt that Eisenstein's influence was even more noticeable in movies made outside Hollywood. Michelson argued that montage was an important intellectual and artistic device in independent films produced after the Second World War, such as those by Maya Deren. Kleiman also noted the influence of other Russian artists, such as émigré actress and producer Alla Nazimova. In his opinion, Nazimova's film Salome clearly reflected traditions of Russian literature, theatre and set design. This movie, along with other movies featuring Russian actors and directors, was seen by American filmmakers and influenced their future work in many subtle ways.

Workers' Film Societies

Elsewhere in the West, in response to the dramatic transformation taking place in the young Soviet Union and the new films emerging from the country, progressives grasped the opportunity to use this new potent medium in their own way. Communists here in Britain became centrally involved early on in setting up workers' film societies from the twenties onwards, as a means of creating opportunities for working people to watch Soviet and other progressive films. Ralph Bond, a foundation member of the British Communist Party, published in the Sunday Worker – a forerunner of the Daily Worker – an appeal for interested parties to get in touch to facilitate the setting up of a London Workers’ Film Society, and the response to this appeal surpassed all expectations.

The Soviet director, Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin had an unprecedented impact on audiences everywhere with its revolutionary montage techniques and searing imagery. This was followed by other, equally powerful and iconoclastic films from the Soviet Union. However, these films were banned for public showing in many countries, including the UK, as they were deemed too inflammatory and seen as dangerous communist propaganda.

The first workers’ film societies were set up to provide a means of showing such films (and they were also seen as a way of getting around the censor, as such films could be shown in private clubs without a licence). The first, founded in London in 1925, had as its object the ‘showing of films of artistic interest, which could not be seen in ordinary cinemas’. Such societies had already been active on the continent of Europe. However, before the new London film society even got off the ground it was already involved in skirmishes with the London County Council (LCC) over permission to show their selected films, even to members. (The LCC was London’s licensing authority for film screenings under the 1909 Cinematographic Act). In 1928, the LCC banned the showing of Battleship Potemkin, and then also banned a showing of Pudovkin’s The Mother. This led many progressive individuals, including J. M. Keynes, Julian Huxley, Sybil Thorndike, Bertrand Russell and George Bernard Shaw, to protest, but even they failed to have the ban rescinded.

When the London Workers’ Film Society’s tried to show two Soviet-made films at the Gaiety Cinema in Tottenham Court Road in November 1929, the cinema owner refused the booking at the last minute after pressure from the London County Council. Such run-ins between the LCC and the LWFS became regular occurrences. While the LCC adhered to its bans on the Soviet films mentioned above, it relented as far as permitting the LWFS to put on Sunday shows in the West End.

After the setting up of the London society, several others soon appeared around the country, and an attempt was made to create a national federation of film societies to facilitate easier access to films, better distribution and co-ordination. The Federation of Workers’ Film Societies (FOWFS) was founded in the autumn of 1929 and led to the creation of a network of local workers’ film societies all over Britain.

The Labour Party itself showed no interest in setting up workers’ film societies but with the success of the London Society, it became highly suspicious of the latter’s activities and denounced the society as being merely a communist propaganda vehicle.

The Communist Charles Cooper was a ‘movie enthusiast whose Contemporary Films opened new horizons for British cinema audiences. His early interest in film had led Charles to become, in 1933, secretary of the Kino group, an association of left-wing film enthusiasts who were determined to circumvent Britain's draconian film censorship, which was especially aimed at the new Soviet cinema. Kino organised 16mm screenings of Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin for trade union and Soviet friendship groups, as well as producing a ‘workers' newsreel’ and agitational films such as Bread, in which a starving, unemployed worker is harshly treated by police and magistrates.

Although Eisenstein is undoubtedly the greatest and most innovative of all Soviet film-makers, his contemporaries should in no way be ignored, as they also made innovative and influential contributions to the film medium. Below I take a cursory look at the most significant.

Dovzhenko

After returning to the USSR from a prisoner of war camp in Germany, Dovzhenko turned to film in 1926 after landing in Odessa . His second screenplay was Vasya the Reformer which he co-directed. He gained greater success with Zvenigora (1928) which established him as a major filmmaker. His following Ukraine Trilogy (Zvenigora, Arsenal and Earth) established his reputation worldwide. Its graphic realism was impressive and inspiring. After spending several years writing, co-writing and producing films at Mosfilm Studios in Moscow, he turned to writing novels. Over a 20-year career, Dovzhenko only directed 7 films.

Pudovkin

A student of engineering at Moscow University, Pudovkin, like Dovzhenko, saw active service during the First World War and was also captured by the Germans. During this time he studied foreign languages and did book illustrations. After the war, he joined the world of cinema, first as a screenwriter, actor and art director, and then as an assistant director to Lev Kuleshov.

Pudovkin adopted a very different approach to Eisenstein. While his films are just as revolutionary as the latter’s in terms of the content and their powerful impact, he took a more traditional approach to narrative. A student of engineering at Moscow University, Pudovkin, like Dovzhenko, saw active service during the First World War, also being captured by the Germans. During this time he studied foreign languages and did book illustrations. After the war, he abandoned his professional activity and joined the world of cinema, first as a screenwriter, actor and art director, and then as an assistant director to Lev Kuleshov .

His first notable work was a comedy short Chess Fever (1925) co-directed with Nikolai Shpikovski. In 1926 he directed what came to be considered one of the masterpieces of the silent era: Mother. In this he developed several montage theories, but in a different way to Eisenstein.

His first feature was followed by The End of St. Petersburg (1927) and Storm over Asia, about the impact of the Bolshevik revolution on what was then seen as a backward region. After an interruption caused by poor health, Pudovkin returned to film-making, with several historical epics: Victory (1938); Minin and Pozharsky (1939) and Suvorov (1941). The last two were often praised as some of the best films based on Russian history, along with the works of his colleague Eisenstein he was awarded a Stalin Prize for both of them in 1941.

In 1928, with the advent of sound film, Pudovkin, Eisenstein, and Grigori Alexandrov signed the ‘Sound Manifesto’, in which the possibilities of sound are analysed, but always understood as a complement to image.

Dzigha Vertov

Vertov attempted to do for the documentary what Eisenstein had been doing in the fictional field. He was born in 1896 and is considered one of the ‘greats’ of early Soviet film-making, a director who concentrated on documentaries. He began by making newsreels but also developed his own theories about film-making that differed markedly from those of the fictional film-makers mentioned above. His work and writing would be very influential on almost all future documentarists, particularly the British school around John Grierson, Basil Wright, Alberto Cavalcanti and Paul Rotha, but also later on the French Cinéma Verité movement.

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, at the age of 22, Vertov began editing for Kino-Nedelya (Кино-Неделя, the Moscow Cinema Committee's weekly film series, and the first Russian newsreel), which first came out in June 1918. While working for Kino-Nedelya he met his future wife, the film director and editor, Elizaveta Svilova , who at the time was working as an editor at Goskino She began collaborating with Vertov, and working as his editor but later his assistant and co-director on subsequent films, such as the iconic Man with a Camera (1929), and Three Songs About Lenin (1934).

Vertov worked on the Kino-Nedelya series for three years, helping establish and run a film-car on Mikhail Kalinin’s agit-train during the ongoing ongoing civil war between the Bolsheviks and the white Russian counter-revolutionaries. Some of the cars on the agit-trains were equipped with actors for live performances and printing presses: Vertov's had equipment to shoot, develop, edit, and project film. The trains were taken to battlefronts on agitation-propaganda missions aimed at bolstering the morale of the troops, and to engender revolutionary fervour and commitment. In 1919, he compiled newsreel footage for his documentary Anniversary of the Revolution, and in 1921 he compiled History of the Civil War.

Kino-Pravda

In 1922, the year that O’Flaherty’s seminal Nanook of the North was released, Vertov started his Kino Pravda series. It took its title from the Bolshevik government newspaper Pravda. Kino-Pravda (Film Truth) continued Vertov's agit-prop bent. The Kino-Pravda group began its work in a basement in the centre of Moscow. It was, as he himself described it, damp and dark. There was an earthen floor and holes one stumbled into at every turn. He said, ‘This dampness prevented our reels of lovingly edited film from sticking together properly, rusted our scissors and our splicers’. ‘Before dawn damp, cold, teeth chattering I wrap comrade Svilova in a third jacket’.

Vertov's driving vision, expounded in his frequent essays, was to capture ‘film truth’—that is, fragments of actuality which, when organised together, contain a deeper truth than can be seen with the naked eye. In the Kino-Pravda series, he focused on everyday experiences, rejecting ‘bourgeois concerns’ to film ordinary people, marketplaces, bars, and schools instead, sometimes with a hidden camera. The episodes of Kino-Pravda did not usually include re-enactments or stagings, although he did so on odd occasions. The cinematography is simple and functional. Vertov appeared to be uninterested in traditional ideas of aesthetic beauty or the perceived grandeur of fiction.

Vertov clearly intended an active relationship with his audience in his Kino Pravda series, but by the 14th episode the series had become so experimental that some critics dismissed his efforts as ‘insane’. Vertov responded to their criticisms with the assertion that the critics were hacks nipping revolutionary effort in the bud, and concludes his essay with a promise to ‘detonate art's Tower of Babel’. In Vertov's view, ‘art's tower of Babel’ was the subservience of cinematic technique to narrative.

With Lenin's admission of limited private enterprise through his New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1921, Russia began receiving fiction films from abroad, a situation that Vertov regarded with suspicion, calling drama a ‘corrupting influence’ on the proletarian sensibility. In this view, he was taking an extreme and, one has to say, very narrow viewpoint. By this time Vertov had been using his newsreel series as a pedestal to vilify dramatic fiction for several years; he continued his criticisms even after the warm reception of Eisenstein’s Potemkin in 1925.

By this point in his career, Vertov was clearly and emphatically dissatisfied with narrative tradition, and expressed his hostility towards dramatic fiction of any kind both openly and repeatedly; he regarded drama as another ‘opiate of the masses’ – a rather extreme position.

The Man with a Movie Camera

In his essay ‘The Man with a Movie Camera’ Vertov wrote that he was fighting ‘for a decisive cleaning up of film-language, for its complete separation from the language of theatre and literature’. By the later segments of Kino-Pravda, Vertov was experimenting heavily, looking to abandon what he considered film clichés (and receiving criticism for it); his experimentation was even more pronounced and dramatic by the time Man with a Camera was filmed in Ukraine.

Some have criticised the obvious stagings in this film as being at odds with Vertov's principle of ‘life as it is’ and ‘life caught unawares’, but its sense of realism is overwhelming. The film has become synonymous with the use of specifically cinematic technique, with the use of double exposure, fast and slow motion sequences, freeze-frames, jump cuts, split screens and tracking shots etc. He also uses footage played in reverse and the idea of self-reflexivity.

In the British Film Institute's 2012 Sight and Sound poll film critics voted Man with the Camera the 8th greatest film ever made and the work was later named the best documentary of all time in the same magazine. Although in the Soviet Union at the time it also had its staunch critics who called it ‘formalistic’ a criticism aimed at a number of Soviet film-makers and artists, including Eisenstein.

Like other Russian filmmakers, he attempted to connect his ideas and techniques to the advancement of the aims of the Soviet Union. Whereas Eisenstein viewed his ‘montage of attractions’ as a creative tool through which audiences would be better able to comprehend complex processes and thus the ideological content of the films, Vertov believed that Kino Eye would have an influence on the actual evolution of mankind, from being a flawed creature into a higher, more precise, form of being. ‘I am an eye. I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, I am showing you a world, the likes of which only I can see’, he was quoted as saying.

There is no doubt that all these pioneering film-makers and theoreticians during the early years of the Soviet Union have had a lasting influence on film-makers worldwide. Despite the fact that many ‘movies’ made today for cinema and television today show all too clearly that their makers should perhaps return to school and learn from these masters, the better film-makers still reveal in their work the seminal influence of those early Soviet pioneers.