Alan Morrison introduces his latest poetry collection, and calls for submissions for his latest anthology of political poetry.

After seven years of what might be termed the ‘welfare hate’, with over 80,000 deaths (and suicides) among sick and disabled claimants between 2011-14, approximately 2,380 within six weeks of the DWP and Atos declaring them “fit for work”, it is only in recent months that the British pathology of what I term ‘Scroungerology’ has shown vague signs of a pausing for thought.

Undoubtedly some factors contributing to this latter cultural hiatus are the United Nations report condemning the Coalition and Tory Governments’ abuses of disability rights through disability-targeted benefit cuts, and veteran social-realist director Ken Loach’s Palme d’Or and BAFTA-winning film intervention, I, Daniel Blake (in some ways a polemical update on Jim Allen and Roland Joffé’s superlative The Spongers, broadcast 1978, which juxtaposes the story of a single mother and her children targeted by punitive disability benefit cuts against the backdrop of the taxpayer-funded Queen’s Silver Jubilee, and which is more than ripe for repeat).

These have come as timely reinforcements to several veteran campaigns –Disabled People Against the Cuts, the Spartacus Report, the Black Triangle Campaign, Calum’s List et al – that have fought valiantly over the past seven years to put the catastrophic impact of the disability cuts in the public domain, in spite of the DWP and a complicit mainstream media’s best efforts to ‘bury’ such issues.

Nevertheless, we have a long way to go politically and attitudinally as a society until we can wrestle back some semblance of a compassionate and tolerant welfare state which looks after the poor, unemployed, disabled and mentally afflicted, and without recourse to stigmatisation and persecution. The front line of ‘scroungermongering’ is the thick red line of the right-wing red tops, most heinously the Daily Express, and, of course, every English person’s favourite hate rag, the Daily Mail – the ubiquitous negative drivers of most public opinion.

To be on benefits today, no matter what one’s personal circumstances or disadvantages, is almost a taboo, and one exploited ruthlessly by the makers of such televisual effluence as Benefits Street, Benefits Britain: Life on the Dole, and the reprehensibly titled Saints and Scroungers (one campaigner, Sue Marsh, has tried to re-appropriate that dreadful term on her admirably defiant Diary of a Benefit Scrounger blog).

In spite of a faint sense of relief felt across the unemployed and incapacitated communities at new Work and Pensions Secretary Damien Green’s announcement that there will be no more welfare cuts beyond those already legislated, there is still cause for trepidation when said legislated cuts of £30 per week to new Employment and Support Allowance claims kick in this April – certainly, then, ‘the cruellest month’ this year.

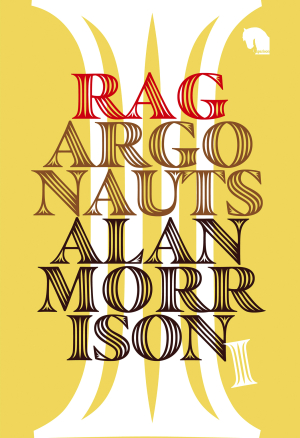

By something of a coincidence, my next poetry collection, precisely on the theme of the welfare and disability cuts and the stigmatisation of the unemployed, Tan Raptures, is published by Smokestack Books on 1 April.

Tan Raptures gathers together poems composed during the past six years of remorseless benefits cuts and welfare stigmatisation. Some of it is from an empirical perspective, my having been for much of this period in the ‘Work-Related Activity Group’ (or ‘WRAG’ as it’s disparagingly abbreviated) of Employment and Support Allowance, where those who are deemed unfit for work for the time being but not necessarily permanently are placed (I am a lifelong sufferer of pure obsessional disorder, an unpredictable and debilitating form of OCD). This has been punctuated by sporadic paid opportunities (termed ‘permitted work’ or ‘therapeutic earnings’ by the DWP) in poetry mentoring, tutoring and commissions.

Poetry and unemployment often go hand-in-hand, if that’s not a contradiction in terms, since writing poetry is a form of occupation (alongside editing it, publishing it, teaching it, mentoring it, workshopping it etc.), even if an often impecunious one as paid opportunities are few and far between. Indeed, the fact that poetry has very little ‘market value’, and employment or occupation in capitalist society is almost entirely defined in terms of earning money, almost all full-time poets are, paradoxically, ‘unemployed’; at least, in purely superficial material terms. Through the sadly seldom-consulted prism of humanistic occupational theory, poetry is certainly an ‘occupation’ in the authentic sense of the term.

Many poets have been unemployed at points in their careers albeit ‘poetically employed’ at the same time. Indeed, unemployment is often an ‘occupational hazard’ of being a poet, and many either still are, or certainly have been in the past, intermittent benefit claimants. Capitalism has no time for poets since it deems them unprofitable and economically unproductive (in any case, it has their occupational replacements: advertising copywriters).

This is in stark contrast to the stipends paid by the state in the old Soviet Union specifically to keep poets in their poetry (a similar scheme would be most welcome here today). The sometimes inescapable relationship between poetry and unemployment – bards on the dole – is almost never spoken let alone written about by poets. Poetry and unemployment are unspoken companions. But many poets will stifle a bitter laugh at the notion of a Department for Waifs and Poets (DWP).

In Tan Raptures I refer to the DWP as the ‘Department for War on the Poor’, since that is undoubtedly its primary purpose today. The collection includes polemical paeans to many victims of the Tory benefits cuts and sanctions, such as Glaswegian playwright Paul Reekie (suicide), ex-soldier David Clapson (death from diabetic complications/malnutrition), and the Coventry soup-kitchen-dependent couple, the Mullins (suicide).

The eponymous polemical poem is an Audenic dialectic in 14 cantos on the social catastrophe of the benefits caps, pernicious red-top “scrounger” propaganda, and Iain Duncan Smith’s despotic six year grip at the DWP. It is also a verse-intervention of Social Catholicism, as epitomised by Pope Francis, in oppositional response to the “appalling policies” (Jeremy Corbyn) of self-proclaimed ‘Roman Catholic’ Duncan Smith.

The title Tan Raptures plays on the biblical notion of ‘The Rapture’ – the ‘raising up’ of living and dead believers to meet their maker in the sky – satirising the ubiquitous ‘tan envelopes’ that strike fear into claimants on a daily basis as passports to a twisted Tory notion of ‘moral salvation’ through benefit sanction.

So common has this phenomenon become that the phrase ‘fear of the brown envelope’ now denotes a recognised phobic condition, and was even used as the first part of a title for an academic paper on exploring welfare reform with long-term sickness benefits recipients’ (Garthwaite, K., 2014).

It is my hope that Tan Raptures will play its part in keeping up the momentum of the belatedly emerging counter-cultural welfare narrative as championed by the likes of Ken Loach, and, of course, Labour’s first socialist leader in decades, Jeremy Corbyn, who put it firmly on record that he opposes any open discrimination against the poor, unemployed, sick and disabled in such reprehensible and hateful terms as “scrounger”, “skiver” and “shirker”.

Our culture of ‘Scroungerology’ has been something I have been writing polemic on for a number of years now at The Recusant and through the two anti-austerity anthologies under its e-imprint Caparison: Emergency Verse – Poets in Defence of the Welfare State (2010/11) and The Robin Hood Book – Verse Versus Austerity (2012/13).

It also seems an apt time then to pitch Caparison’s belated third poetry anthology, The Brown Envelope Book, or The Brown E-Book for short, since it will be, at least initially, an electronic publication, as was, originally, Emergency Verse.

The main theme of this third anthology is, as the title suggests, benefits cuts and welfare stigmatisation, but it will also be addressing the housing crisis by petitioning for the reintroduction of private rent controls and also raising greater awareness of the prevalence of letting agent-and-landlord negative vetting of prospective tenants on the basis that they claim benefits or Local House Allowance (even if they’re in work!).

Poets of all stripes are invited to submit their poems on the themes of unemployment and welfare; the empathic but, more especially, the empirical, welcome.

Alan Morrison’s Tan Raptures is published by Smokestack Books. It is available now to order at: https://www.waterstones.com/book/tan-raptures/alan-morrison/9780995563506. To submit work for consideration in The Brown E-Book, please email up to six poems along with a brief biog in the body of the email to: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Please put ‘Brown E-Book’ in the subject header.

Sixth Rapture: Shut Curtains during the Day

Unlike riches, policies do have a trickledown effect,

And the dictates of Damascus Smith –hairshirt Thomas Malthus

Of Caxton House/or Gregor Mendel of the DWP–

Would germinate into a pearl-white species of cropped

Correspondences in Kafkaesque script bespeaking strange augurs,

Barbed inferences, grim omens, pointed portents –vatic tans

Vibrating with cryptic stings: ‘A query has arisen regarding

Your claim…’, or, ‘We are letting you know what might happen to you’,

But without actually doing so, only adumbrating through

Deliberate ambiguity and mystique of omission (the old

Hemingway tip-of-the-iceberg effect), lacings of uncertainty,

Leaving the door wedged open to auto-suggestion, taxing

Anxious imaginations prone to catastrophic projections –

The implicatures captured uniquely in tan paper raptures;

While elliptic and ecliptic occupational purposes, strange

Occulting ranks and titles, Customer Compliance Officers,

Brought thoughts of Thought Police or plain-clothed

Gestapo in tan macs with glacial stares behind impenetrable

Spectacles turning up on doorsteps clutching rolled umbrellas

And black leather briefcases stuffed full with thumbscrews,

Coat-hangers, piano wires, tape-recorders and lie-detectors –

While Government encouragement of neighbourly petit-

Espionage on unemployed suspects (more the ‘Big Brother

Society’) upped the tan ante for vigilante attitudes

And raised the temperature spiking the thunderous atmosphere

To puncture-point as Ministers instructed conscientious

Citizens to take note of those windows with “shut curtains

During the day” –or, in Baronet Osborne’s vocabulary:

“Closed shutters”– as they left for work each morning: dawn

Patrols of resentful workers directed to mark front doors

Of suspected Dole-Judes, like so many beady-eyed jackdaws –

It’s a peculiarly English kind of malice that criminalises

Innocents and victimises victims of circumstances thrust

On them by others’ “tough choices” and “difficult decisions”…

How appropriate that the Department for War on the Poor

Should send out such vindictive missives in envelopes

Of various browns, parcelling captured sunlight

To disinfect the disaffected, frightened, forgotten, pilloried,

Persecuted, tarred-and-feathered benefit spendthrifts

And profligates, scapegoats and targets for the ran-tan tanning

Of stigmatising tans –what strange types of benefits that grant

No benefits, neither to wallet nor wellbeing, but only

Deplete peace of mind and suppress appetites of “useless eaters”,

“Asocial” and “arbeitsscheu”–is that part of the point, to soften

The blow of swallowed-up cash-flow by shrinking stomachs

So there’s less need for food but more room for souls to grow

Like tapeworms of purely spiritual appetites distending

Themselves on the carroty acid reflux of phantom

Mastication, swishing round in rapturous backwashes from

Half-digested papers…? Some recipients experience

Epiphanies: eat the tan envelopes, as if they were unleavened

Victuals, bellies booming out with brown Holy Ghosts…

from 'Tan Raptures' (Tan Raptures, Smokestack Books 1 April 2017)