Building Jerusalem

Christopher Rowland discusses William Blake's visionary approach to art, religion and culture generally, and how his 'mental fight', or cultural struggle, inspires us to build a new Jerusalem, a better society.

William Blake was a visionary poet and artist, whose works have achieved a central place in British culture. Some of his verses, widely known as 'Jerusalem', which he wrote at the opening of one of his longer poems, ‘Milton’, have become an unofficial national anthem, and a very necessary alternative to the English national anthem for those of us with republican commitments. As with so much else in his writings, these verses are full of biblical themes, like a ‘chariot of fire’, and 'building Jerusalem', used in Blake’s own way. The words stress the importance of people taking responsibility for change and building, through cultural struggle or 'mental fight', a better society ‘in England’s green and pleasant land’.

Although he was a visionary, he was not a dreamer cut off from the realities and complexities of experience, particularly the poverty and oppression of the urban world in which he lived for most of his life. He had an amazing insight into contemporary economics, politics and culture, and was able to discern the effects of the authoritarianism of church and state as well as what he considered the arid philosophy of a rationalist view of the world which left little scope for the imagination.

He abhorred the way in which Christians looked up to a God enthroned in heaven, a view which offered a model for a hierarchical human politics, which subordinated the majority to a (supposedly) superior elite. He also criticised the dominant philosophy of his day which believed that a narrow view of sense experience could help us to understand everything that there was to be known, including God. Blake’s own visionary experiences showed him that rationalism ignored important dimensions of human life which would enable people to hope, to look for change, and to rely on more than that which their senses told them. All people needed to be aware of and allow to flourish the ‘Poetic or Prophetic character’ latent in them.

Blake had no time for conservative Christianity’s infatuation with the Bible as the ‘supreme authority’ in the life of the church and society. Such sentiments were a symptom of false religion, which contracted out responsibility for biblical interpretation to priests and scholars. All God’s people, inside and outside the churches, have the responsibility to attend to the energetic activity of the Spirit in creation, in history, and in human experience. The Bible had to be seen for what it was – a mixed collection of texts which might make a contribution to human betterment.

Blake loved the Bible because it acted as a stimulus to an imaginative engagement with society and also with theology. But Blake wasn’t just an interpreter. To paraphrase his own words, he wanted through his words and images to ‘cleanse the doors of perception’. Changing how one looked at the world and behaved in it were central for him. Blake’s comment that what he wanted to do in his work was ‘rouze the faculties to act’ parallels Marx's famous dictum on philosophy, 'Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it'.

That meant empowering the readers and hearers of texts and pictures to have the courage of their convictions and not be dependent on the experts to tell them what a text or picture meant. Too much study of the Bible is, he thought, either completely dismissive of it or excessively reverential and doesn’t allow for creative, imaginative, engagement with it.

The Bible for him was a resource to stimulate understanding, and not a book of moral precepts. Blake is indignant about those elements in the Bible which have been used to condone injustice. He doesn’t attempt to make the Bible internally consistent, or universally benevolent, and he fully embraces its problematic elements as a means to question dominant readings within politics and religion.

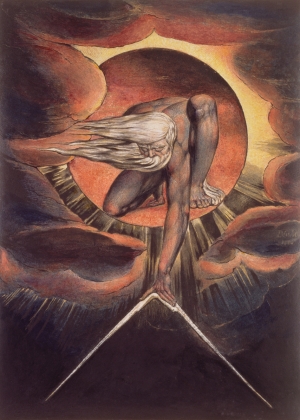

In particular, he challenges its depiction of God as a remote monarch and lawgiver, and the use made of such imagery to justify patriarchy and authoritarianism. His astonishingly diverse array of poems, engravings, and paintings, permeated as they are with biblical themes, make Blake simultaneously both England’s greatest Christian artist, and also one of its most radical biblical interpreters.

‘Would to God that all the Lord’s people were prophets’, he wrote, thereby including all in the task of speaking out about what they saw. Prophecy for Blake, however, was not the prediction of the end of the world, but telling the truth as best one can about what one sees, fortified by insight and an ‘honest persuasion’ that if 'the doors of perceptrion were cleansed, things could be improved.

One observes, is indignant and speaks out. It’s a basic political maxim which is necessary for any age. Blake wanted to stir people from their intellectual slumbers, and the daily grind of their toil, to see that they were captivated in the grip of a culture which kept them thinking in ways which served the interests of the powerful.

The beautiful little poems which make up 'Songs of Innocence and Experience' contain some of Blake’s most profound political insights, in deceptively simple verses. Three poems, one entitled ‘London’, the other two a contrasting pair entitled ‘Holy Thursday’, exemplify the way in which Blake engaged his politics. He didn’t do this by grand pronouncements but by attention to what he termed ‘minute particulars’.

In ‘London’ he imagines himself like the biblical prophet Ezekiel, walking round the streets of Jerusalem, and seeing people marked with ‘marks of weakness and marks of woe’, because of the poverty, injustice, hypocritical social convention, and the stranglehold of emerging capitalism. And he observed what he called the ‘mind forg’d manacles’ of cultural conformity which stopped people comprehending the injustices around them.

In the two 'Holy Thursday' poems we have contrasting perspectives on the social situation in England. On the one hand, the poet describes a festive event in St Paul’s Cathedral, in which children who are recipients of charity come to thank God. On the other, there is a hard-hitting critique of what life is actually like for most children, in ‘this green and pleasant land’ -

‘Babes reduc'd to misery. Fed with cold and usurous hand’

The ‘Holy Thursday’ poems offer readers the opportunity to meditate upon late eighteenth century England through the lens of a particular social event.

All people, inside and outside the churches, according to Blake, have the responsibility to attend to the energetic activity of the divine spirit in creation, in history, and in human experience. He wouldn’t have wanted his words to become a sacred text, any more than the words of the Bible, but an ongoing stimulus to politics and religion in the struggle to realise that (as he puts it in ‘Jerusalem’) ‘every kindness to another is a little Death In the Divine Image nor can Man exist but by Brotherhood’.

His work has enabled ordinary people to recognise that culture matters, and that there are mental and cultural chains, as well as economic chains, which bind us. He sought to affirm the importance of everyone in the struggle for community and human betterment. I feel sure he would have been sympathetic to the aims of this website, and proud to see his verses used to help 'build Jerusalem'.

Christopher Rowland is the Dean Ireland professor of the Exegesis of Holy Scripture Emeritus at the University of Oxford.