Martin Gollan

Martin Gollan paints but also works with print and video. He recently has been working with local charities and their beneficiaries to dynamically illustrate the impacts of austerity and welfare reform.

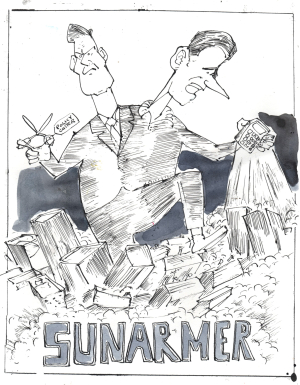

Sunarmer

Not racist just rude

Integrity, Professionalism and Accountability?

Risgi Sunak promised us 'integrity, professionalism and accountability' when he became leader of the Tory party.......

Electoral extinction for the Tories? It's just around the corner

Four Horsemen

One law for the rich........

The three wise monkeys: rich, powerful and extremely alert......

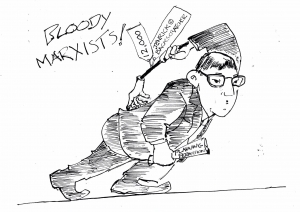

The frackers are fracking off

Cabinet minister Andrea Leadsom has admitted the fracking suspension imposed by the government is a “disappointment”, as the Conservatives face escalating pressure to introduce a permanent ban. Her remarks came as environmental campaigners hailed the announcement of a moratorium on fracking in England, declaring it a victory for communities and the climate.

She said it was clear the government “must impose this moratorium until the science changes”, but added shale gas is something the UK “will need for the next several decades”. When pressed on why a permanent ban is not being implemented by No 10, she replied: “Because this is a huge opportunity for the United Kingdom”.

However, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn yesterday dismissed the move as an election stunt. “I think it’s what’s called euphemistically a bit of greenwash,” he said. “I think it sounds like fracking would come back on the 13th of December, if they [the Conservatives] were elected back into office. “We’re quite clear, we will end fracking. We think it’s unnecessary, we think it’s pollutive of ground water systems, and is actually dangerous and has caused serious earth tremors.”

Reports taken from the Independent and The Guardian.

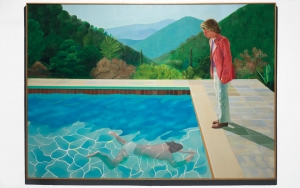

Hockney's Portrait of an Artist: A perfect expression of gross inequality

Martin Gollan argues that what we see when we look at this Hockney painting is a perfect expression of the gross inequalities created by neoliberal capitalism.

What do we see when looking at a painting which some has paid $90,312,500? This was the price paid a few weeks ago, for lot 9C, David Hockney’s ‘Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), at Christies auction in New York, of postwar and contemporary art.

An artist might note the composition (based on the chance positioning of two photographs in Hockney’s studio) and colour scheme, capturing the intensity and brightness of California (though the set of photographs eventually used as reference for the painting were taken in the south of France and London).

The critic or art enthusiast might note that Hockney, despite his growing success and lingering association with 60’s Pop, was, in the early 70’s, working against the tide of late modernism, dominated at this point by conceptualism and performance - an attempt by artists to de-commodify the artwork and circumvent the market.

Meanwhile, the collector or investor may recognise an opportunity to state his (its is statistically more likely to be his rather than her) cultural hegemony and to invest in the gravity-defying asset class, Fine Art.

Hockney’s ‘Portrait of an Artist’ has it seems always been considered primarily a financial asset, rather than a painting made at an emotionally turbulent juncture in Hockney’s life, and having intense personal significance for the artist. The standing figure in the painting is Peter Schlesinger, who Hockney met in 1966 and became his partner until their relationship broke down in 1971.

A first version of the painting was finally abandoned after Hockney failed to solve a number of technical problems with the original composition. The second version was completed in just two weeks, in time for a solo exhibition at the Andre Emmerich Gallery in New York in 1972.

Hockney, in his 1976 book Hockney on Hockney, tells how the painting was bought for around $18,000 before the exhibition opened, and was then shipped to a London art dealer before going to Germany where it was re-sold for around $50,000 (the equivalent of $290,000 today). Hockney had apparently warned Emmerich Gallery not to sell to European dealers because they were only interested in quickly re-selling at a profit.

Hockney has long been among the most popular and publicly recognisable of contemporary British painters, despite critics and academics often being sniffy about his work. His most recent (from about the mid-nineties onward) landscapes painted in his native Yorkshire appear to have cemented his place in the affections of the general public (meantime, the critic Adrian Searle, reviewing Hockney’s 2012 Royal Academy exhibition, accused the painter of lacking ‘touch’ and too often fighting ‘slickness or too much style’).

What does it mean now that one of Hockney’s paintings has the most expensive price tag ever paid for a living artist? Probably not much. Five years ago the ‘honour’ belonged to Jeff Koons when his stainless steel sculpture, ‘the Dog of Balloons (Orange)’ sold at Christies for $58.4 million. Before long another artist will replace Hockney as the art market becomes yet further remote from everyday economics.

Speaking about the fate of “Portrait of an Artist” after the Emmerich exhibition, Hockney claimed not be as wealthy as generally supposed; a mistake based on the high prices, even in the 1970s, of his paintings' resale prices. He admitted nonetheless to being not “badly paid”. Fast forward to 2010, when DACS, which campaigns for the royalty rights of artists, reported that the median salary for a visual artist was £10,000. In 2010 the Joseph Rowntree Foundation set its minimum income standard for a single person at £14,400, before tax.

What do we see when looking at painting worth $90.3 million? Nothing more than a perfect expression of the gross inequalities created by neoliberal capitalism, and economic policies that cosset and protect the wealth of the rich while making the lives of those on ordinary incomes or benefits “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short”.