Fran Lock interviews Alan Morrison about Anxious Corporals, a polemical and poetic history of post-war working-class culture, which can be ordered here

Fran Lock: Hi Alan, thanks for taking the time to talk to me about Anxious Corporals. The term ‘anxious corporals’ was first coined by Arthur Koestler to describe working-class servicemen with a need to ‘satisfy some/ Vitamin deficiency of the mind’, not for the purposes of self-advancement, but to fill some kind of existential void or to make sense of the fragile and threatening world around them. I wonder if you could start by talking a little bit about this feeling of anxiety, which is communicated in the language and restless lyric flow of the poem. Do you have any thoughts about why, at a contemporary moment that is surely ever more precarious and insecure, there doesn’t seem to be a corresponding drive or thirst for knowledge?

Alan Morrison: Anxiety is underneath everything I do, particularly creatively, it’s the conductor of my thoughts and words and ideas; also an obsessiveness, which very much comes through in the obsessional pull of this poem, of the phrasings punctuated only with commas, giving a breathless almost panicky quality.

Creativity and self-expression are essentially anxious acts. Arguably life itself is a state of anxiety, of anticipation, apprehension, excitement, dread, I take quite a Kierkegaardian angle (which can also be exhausting). But on a more personal level, I’m a lifelong sufferer of anxiety so I suppose this comes through in what I write, and what I write about.

My tendency to compose in an almost stream-of-consciousness outpouring of lines and phrasings with only commas is something that’s crept into my poetry in the last couple of years. It’s not really a conscious thing, it just feels natural to me now, and more liberating, to write in this way, for some reason I’ve come to hate full stops, even to the point that I end stanzas and poems with ellipses (i.e. dot dot dots) – full stops look too final, and it feels absurd to me that any thought or thoughts, often profound, especially as expressed in a poem, for example, ever have a definitive end as signified in a full stop: thoughts and feelings and sensations are continuous or recurring, they are tortuous, they loop, they collect and disperse and collect again, like starlings, hence for me it feels completely inappropriate to end a verse or a poem with a full stop.

Within verses and poems I find commas less intrusive, and occasionally I use semi-colons as stitches between different trains of thought; but commas seem to me the most poetically accommodating of punctuation marks, helping the poem keep a constant cadence and flow, each line, phrasing seeping into the next, like thoughts, like feelings…

On the other part of your question, I think the irony today is that with ever greater resources for communication and information the novelties in those areas have diminished rather than expanded, the sense of curiosity blunted, it’s as if a kind of generational ennui has set in, you see perhaps the ultimate triumph of commodity-based consumer capitalism in the sight of families and friends sat at cafes scrolling through their phones rather than conversing properly, the ultimate individualisation, almost a form of mass-solipsism - but which ultimately is just another form of conformity.

It’s impossible to generalise of course. No doubt there are sections of society, certain types of people who do still thirst knowledge, but a lot of the time the knowledge sought might not be the most enlightening. But ultimately what such vast archives of easily accessed knowledge such as on the internet seem to have achieved is an increasing craving for instant gratification, an impatience, a poor concentration, an attitude that seems to expect everything to be immediately explainable at the touch of a button. But most things aren’t instantly explainable, many things require very active application, long studied reading and processing.

FL: Related to the last question, it occurred to me that we have unprecedented access to all kinds of knowledge today, and that in theory at least, education – both formal and informal – is more readily available to us than ever before. Despite this, Anxious Corporals is excoriating about the demise of critical thinking among working-class cohorts, and I think one really significant aspect of this book is its understanding of this demise as something that is also done to us, deliberately, politically, over time.

I was particularly struck by your critique of relativist or postmodern discourse, which tries to ‘prove/ Everything is relative, ultimately subjective, intrinsically/ Ironic, endlessly reductive’. I’m reminded of the ways in which these ideas were used cynically within the space of the university to re-establish the status quo, following decades of radical ferment during the sixties and seventies. Throughout this period there was a great deal of on-campus activism, but also a profusion and merging of solidarities inside and outside of the academy, with a huge rise in worker-student alliances.

Postmodernism was deployed in this context to convince students that nothing is true. If activism begins with the basic assumption that some ideas and actions are right, and that others wrong, then undermining this conviction removes the motivation to protest. Being heavily jargonistic, postmodernism also undermines the ability of those inside the academy to speak clearly and coherently to those outside, reinforcing a sense of elitism and hierarchy. Finally, there is the attack on kinship through an absolute insistence on identity-driven subjectivism. Nauseating, and I think one of the things Anxious Corporals is really acute on is articulating how this toxic creed spills out of the academy and is deployed by neoliberal culture more broadly.

Could you say something about how this kind of neoliberal postmodern malaise has affected the way in which working-class cohorts understand ‘knowledge’, how we access knowledge, and how postmodernism has whittled down and shaped the value placed on intellectual curiosity, education, and ‘facts’?

AM: Yes, absolutely, when we think of the internet and its vast repository of information readily available for pretty much anyone to access today (bar maybe those families at the lowest economic scale who perhaps can’t afford phones or computers), a greater democratisation of knowledge if you like, then the past arguments that whole sections of society are unable to access these areas and are thus significantly handicapped in attempts at self-education (though there have always been libraries!) would seem less credible, ostensibly.

I say ostensibly, since of course one has to some extent to know or have some clue as to where to look for certain types of knowledge; okay, so Wikipedia is very prominent and easily accessible on pretty much any subject today, but there still might be barriers of literacy, and domestic demands on time and concentration in those families that are materially impoverished; as I learnt myself as a teenager struggling to learn anything much at school, poverty is not very conducive to learning.

However, in spite of growing up in relative poverty, which had been the result of lots of bad luck on my parents’ part, I had other advantages that many of my working-class and disadvantaged schoolmates didn’t have: my parents were both essentially middle class, they’d not been educated at public schools, but my father had been to a good quality grammar school, while my mother, though from a more working-class background originally, had been partly educated at a convent school, and then had had elocution lessons when she was a young aspiring actress (though she didn’t in the end pursue that career, instead deciding to settle and have a family; she had at one point been a teacher at a fairly prestigious primary school but thereafter had worked as a dental nurse, dinner lady, auxiliary nurse).

So my brother and I grew up in an atmosphere of educational and cultural aspiration, encouraged by fairly well-educated parents, and in my father’s case, well-read. The atmosphere of our upbringing was bookish. But materially we were pretty impoverished for the entire period of our secondary education, during which my father through no fault of his own suffered periods of unemployment. After leaving the Royal Marines in 1967 (AC is part-dedicated to him since he was a Corporal, and an anxious one at that!),he had gone into the civil service and worked in London in different government departments, but after our move from Worthing to Cornwall he had found it extremely difficult to get back into the civil service and eventually ended up working as a security guard for the rest of his working life; he was what sociologists would call a ‘skidder’, someone who has skidded down the occupational ladder. My mother worked as an auxiliary nurse in an old peoples’ home. Both of them were on very low wages and worked punishing shifts.

I suppose I’d describe my family background as lapsed middle class, one of faded gentility, the perennial shabby-genteel; financially and materially we were very much on the working-class level, if not actually below that at various periods (sufficiently poor that I have memories of often going to bed hungry).

So it wouldn’t be entirely accurate for me to claim to speak on behalf of the working classes since mine was a mixed-class background: I think this is a category that even sociology has yet to fully get to grips with. It meant that our kind of poverty was particularly severe in terms of social isolation, since we were not part of any broader and similarly disadvantaged community and lived in a small hamlet which only added to our sense of remoteness from everything. But suffice it to say that I agree that much of this cultural deprivation is ‘done to’ people and of course we see this mass effort of ignorance-promoting misinformation deployed daily through the right-wing red top press, which also completely corrupts our democratic process through its mass hypnotism of vast sections of the population towards voting Tory or the nearest equivalent. Tabloid editors would argue it’s patronising to say so, but what could be more patronising than the presumption that the working classes want to read the anti-intellectual, culturally philistine and politically reactionary tripe that they spoon-feed them?

When I wrote AC I was very angry, perhaps not completely fairly but I felt I’d lost a lot of sympathy with certain sections of the working classes for voting for Brexit in the Referendum. Back in the Eighties many had fallen for the false promises of Thatcherism, which resulted in the spiritual crippling of our culture and society and lasting scars that have still yet to heal; so when so many seemed to fall for the xenophobic populism of Farage, Johnson and Vote Leave, I just felt so frustrated, betrayed and, well, just angry, angry at what I saw as seeming mass ignorance. And then the final nail in the coffin was the ‘red wall’ in the Midlands and North turning blue in December 2019 – how could such huge swathes of the working classes vote for someone so transparently dishonest, unprincipled, unscrupulous and out of touch as Boris Johnson…? How on earth could they perceive an upper-class narcissist like Johnson as representing their interests…?

Of course the red top press has much to do with this, targeting the working classes as it does, but does there come a point when the Left has to stop and ask, to what extent can we blame the tabloids for proletarian attitudes and voting choices? Is there an element on the Left of our sometimes infantilising the working classes by perceiving them as constant victims of circumstances, and assuming to abdicate all responsibility on their behalf, treating them like overly impressionable children who are easily ‘taken in’? (I say working classes as opposed to working class since they’re/we’re not a homogenous mass of course). The Sun and the hard-right Daily Express might well be daily appealing for their attention in every newsagent, but there is also the Daily Mirror, also a tabloid, but a Labour-supporting one, which has a similar ‘celebrity gossip’-pulling power as its right-wing competitors; and the Morning Star, though not available everywhere, is ostensibly presented in an accessible tabloid format. These are just things I’m throwing in the air, they’re open for debate, I’m ultimately still in a quandary about it all.

The study in working-class Toryism, Angels of Marble, which I excerpt extensively in AC, provides us with many depressing and uncomfortable answers to the conundrum of blue-collar Conservatism, and it really is vital information which still applies today and is something so fundamental to British society that it has to be understood and combated by the Left into the future if we’re ever to break the right-wing hegemony of our political system (though personally I think the only real solution to neutralising the Tory monopoly in the long term is proportional representation – something which might come in time through petition, protest and perhaps an electoral referendum, and maybe one day will be rooted out just as rotten boroughs were in the 19th century).

FL: I also wonder to what extent you think that capitalism – and Thatcherism in particular – has succeeded in devaluing education in and of itself, if it is not connected to some kind of quantifiable economic ‘success’?

There’s a kind of grotesque instrumentalisation of intellectual effort at play within capitalism, which goes hand-in-hand with a carefully cultivated suspicion of – and hostility towards – ‘knowledgeable people’ from those organs and institutions supposed to represent working-class interests and ideals. This is beautifully and bleakly communicated by both yourself and Richard Hoggart, who you quote from extensively throughout Anxious Corporals, in section XII. In this section you also talk about the general distortion of working-class values by capitalism and through culture. Hoggart published The Uses of Literacy in 1957, but this process is horribly ongoing.

Could you speak about this process of distortion and some of its most recent manifestations? Is it a trend that you also see reflected in contemporary poetry?

AM: Oh absolutely, the primary preoccupation of capitalism and all capitalist governments is economic productivity and this is why there is such lack of interest in and low tolerance of Tory ministers towards the Arts and Humanities in academia, as these areas are not perceived to be particularly productive economically nor geared towards capitalist/Tory notions of societal progress which they see as almost solely invested in the sciences and technologies – this betrays the philistine materialism of much Tory and capitalist thought (if it can be called thought at all).

This is why we’re now seeing governmental disengagement with the Arts and Humanities, not only in terms of funding in the universities but also in wider culture. Moreover, the Tories tend to also see the Arts and Humanities as an intellectual threat to capitalist dogma and hegemony, particularly subjects such as Sociology and Cultural Studies. To use the old adage, capitalism ‘knows the price of everything but the value of nothing’.

There is definitely a cultural hostility towards ‘knowledge’, to some extent there’s always been a philistine seam to the British mentality, but our society became very actively anti-intellectual since the Thatcherite revolution, neoliberalism is the ultimate bourgeoisification of culture in terms of promoting mediocrity and banality (e.g. celebrity culture), imagination is distrusted, everything is trivialised to the lowest common denominator, individualism encouraged but individuality mystified and even stigmatised.

I think this anti-intellectualism and, indeed, anti-idealism, has permeated contemporary poetry for some decades now in the postmodernist mainstream, there’s long been a culture of stylistic policing which increasingly homogenises the medium, and so one has to look elsewhere, to the fringes, the small presses, to find the most interesting and authentic poetry being published. For a long time, certainly through the Nineties and Noughties, political poetry was generally frowned upon and belittled by the literary establishment and shunned by mainstream imprints (notable exceptions were presses such as Smokestack, Five Leaves, Flambard and a few others).

It took the financial crash and the onslaught of Tory austerity, then Brexit, then Trump, to jump-start the poetry mainstream into more active political consciousness, but even then it’s been on catch up. As I’ve written before, in a polemical monograph ‘Reoccupying Auden Country’, published at The International Times in 2011 (http://internationaltimes.it/reoccpying-auden-country/) and then reproduced in The Robin Hood Book – Verse Versus Austerity, postmodernism is peculiarly ill-equipped to tackle socio-political topics.

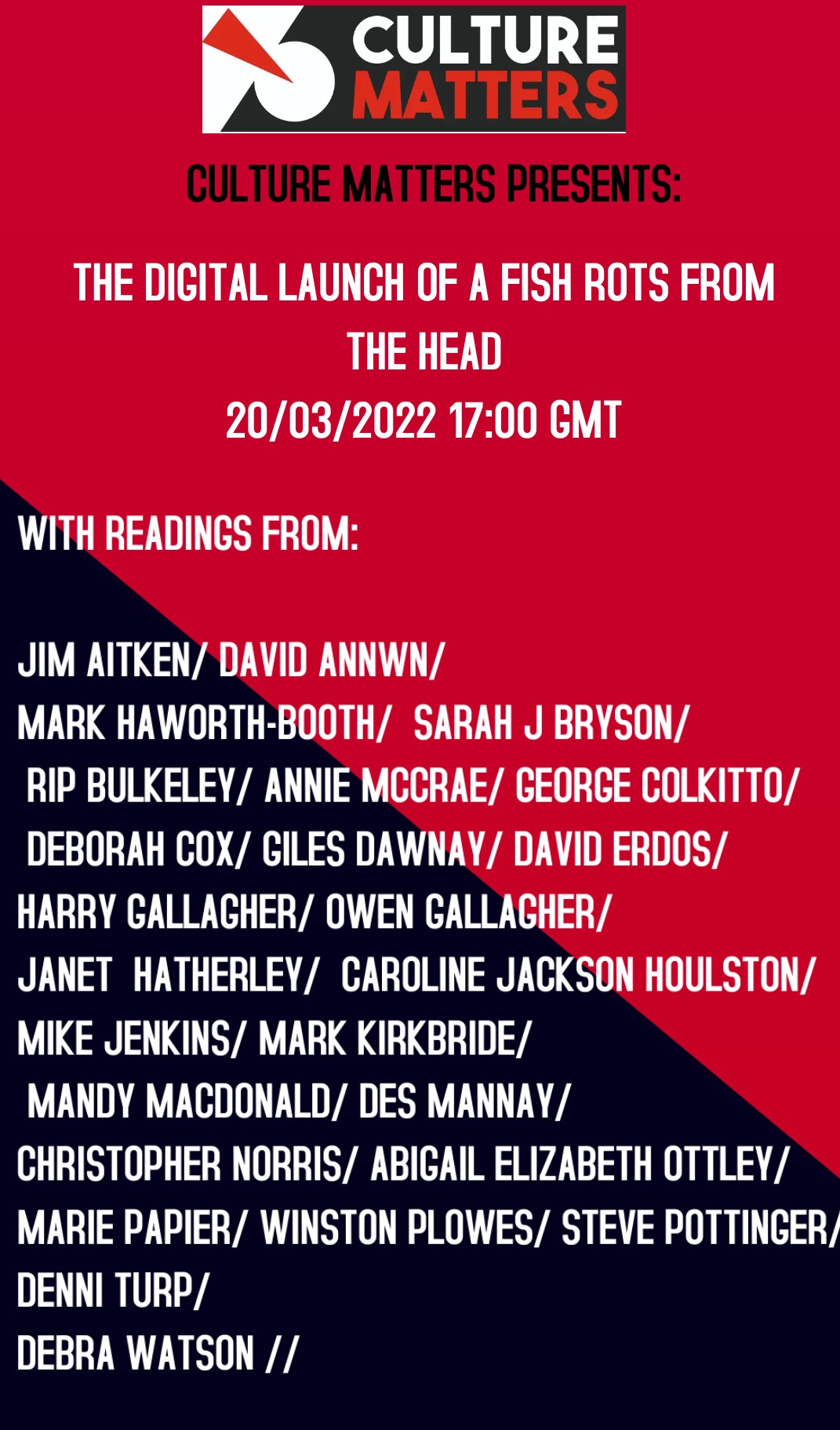

But there has been a slow continuing politicisation of poetry over the past few years, something like a depth-charge, which is has infiltrated the mainstream to some extent, though nowhere as markedly and authentically as through such auspices as Culture Matters, Smokestack Books, the Morning Star, the Communist Review, poetry journals such as Red Poets and The Penniless Press, and other such politically engaged outlets, that have been doing this since long before the mainstream picked up the scent. Nonetheless, at the upper echelons of the poetry scene, the trend is still, stubbornly and increasingly towards social irrelevance, individualism, poetic solipsism, and attitudinal narcissism – selfie-poetry.

FL: Following on from that last thought, I wonder to what extent you see poetry as a potential site of resistance to this distortion of working-class values by capitalism; a kind of redoubt against mass or – to quote Hoggart – ‘synthetic culture and intellectually-vetted entertainments’?

AM: Yes I think poetry can be a form of creative resistance, of polemical response through poetic self-expression to political events, but at the same time it can also end up being co-opted by the capitalist powers and upper echelons, and there are excerpts I include in AC from Ken Worpole’s exceptional polemic Dockers and Detectives that specifically touches on this phenomenon. Richard Hoggart’s Uses of Literacy, too, is an extensive polemic about the dumbing down of mass culture which he documented way back in the late 50s, which was still well within the post war social democratic consensus. I’ve yet to read any of Hoggart’s later writings but I can only imagine his sense of complete despair at how things sped up in these respects through the Eighties and beyond.

But to return to poetry: in a sense, being arguably the least economically productive or enriching artistic medium, it has nothing to lose in being as political, as oppositional as it can be (and yet so much of it is so conservative!); it’s a medium belittled by the capitalist establishment, if not openly despised for its impecuniousness, and thus deeply distrusted. Poetry can be weaponised, more spiritually than politically I think, in the sense that it is something materially transcendent, since it has such little material incentive, and this gives it an unpredictable power all its own. Most of this power is in metaphor – metaphor is both weapon and camouflage.

FL: My own take has always been that poetry requires of us – both as readers and writers – such deep, sustained attention to the operations of language, that it offers a kind of antidote to the passive content-imbibing we’re encouraged to participate in by other forms of literature and media. This leads me with a numbing inevitability to Insta-poetry, and the commercially successful pap that’s pumped out in its name.

One of the things I love about Anxious Corporals is that it is the absolute opposite of Insta-poetry. It’s knotty and complex, rich, allusive, rigorous and dense; it demands and rewards the reader’s non-trivial attention. It doesn’t offer these neat little parcels of peaceable catharsis. It’s troubling and difficult on the level of ethics and ideas. I suppose what I want to know is to what extent you see the cynical and sinister operations of capitalism through the rise of Insta-entrepreneur figures like Rupi Kaur and ‘Atticus’? Do you feel that the commercial ascendancy of such figures under the banner of ‘poetry’ is capitalism’s attempt to colonise or absorb the one form of literature it hasn’t yet successfully assimilated?

AM: I’ve no problem with accessibility and even simplicity in poetry, when it is appropriate for the subject or the tone or purpose of the poem, but I think people have the right to expect from apparently simple poems that, like Blake’s Songs of Innocence, there are other levels which the closer reader can discover under the ostensibly accessible surface.

Complete simplicity in and of itself in poetry –and any medium– inescapably morphs into the commonplace, quotidian, banal, into truism or platitude; there needs to be something else to it, engagement with language, symbol, metaphor, aphorism, something that lifts it beyond the trite or trivial. Ultimately I’m much more exercised by dumbing down or casualisation of literature.

But yes, capitalism absolutely tries to absorb or colonise any artforms that otherwise might pose some sort of threat such as becoming widespread or popular outside of its control. You see this increasingly in bank and building society adverts using spoken word artists, often from BAME backgrounds, in order to give the impression these corporate organisations somehow stand for inclusivity and are there to serve ordinary people, as opposed to profiting out of them.

FL: Connected to this last idea, I wanted to ask you about the notion of ‘accessibility’, both in terms of literature in general and poetry in particular. One of the beautiful things about the Pelican imprint – which is evoked throughout Anxious Corporals as both an emblem of working-class intellectual curiosity and a visual metaphor for the loss of this vital drive – was that it placed the tools of education within the working man’s material reach. These books were readily available in places working people were likely to frequent; they were easily identifiable, they were portable, and they were cheap. In other words ‘accessible’ in the truest sense.

One quietly disturbing trend in contemporary culture has been this shift in emphasis from ‘accessibility’ as equality of opportunity in terms of affordability and distribution, to being ‘accessible’ in terms of content, style or form. This has allowed any work that is challenging or nuanced or risk-taking to be positioned as ‘difficult’ or wilfully ‘alienating’, and this stance meets demands for richness, rigour and innovation with accusations of elitism. Is this something you feel aware of, maybe even write against? Could you tell me if it is something you have experienced in terms of the critical reception of your own writing? And to what extent do you see publishers like Smokestack as inheritors of Pelican’s mission?

AM: Yes, as AC pays to tribute to, Pelicans were originally sold in outlets such as Woolworths, purposely to target working-class readerships – this was a huge part of the Pelican ‘brief’, it was at the core of its publishing mission: to make knowledge, and mostly that hitherto perceived as ‘highbrow’ knowledge, readily available to the masses, cheaply priced, and accessibly communicated, but in no way that meant dumbing down, Pelican books were usually very well-written, often by leading thinkers and intellectuals of the time, but they were presented in an accessible and affordable format so as to attract the ordinary person on the street and give them access to hitherto cordoned-off rooms of information. Pelicans gave opportunities for true self-education on a wide variety of subjects. I agree with you that the perception of what ‘accessibility’ seems to mean today is in terms of over-simplifying. Crucially Pelicans still required intellectual effort from the readers, but glossaries elucidated all jargon.

Yes I suspect that much of my poetry is perceived as a bit ‘difficult’ at times, and on precisely this subject there was one review of AC which was generally positive but in which the reviewer took me to task for not making the poem a bit more accessible, mostly in terms of its presentation, density and, presumably, the absence of any glossary or notes. So perhaps with AC I didn’t quite hit the ‘accessibility’ mark of the very Pelican mission it’s partly paying tribute to.

If so, this was not a conscious thing, but basically down to space restriction, page count limit, and having already practically cut the poem by around 50% believe it or not – it was originally of truly epic proportions, now it’s a mere epic poem

And yes, absolutely, presses like Smokestack, and Culture Matters, and a handful of others, are indeed the poetry-equivalent to Pelican in many respects, and of the Left Book Club, while in the wider polemical field there are presses like Zed Books, Verso, Pluto, Lawrence & Wishart et al, and, indeed, a newly resurgent Pelican and Left Book Club. And online we have Prole, Proletarian Poetry, Poets’ Republic, Culture Matters, and of course my own The Recusant and its imprint Caparison, and Militant Thistles.

FL: Something else I’d like to ask about is the lack of funding this project received. I mention this because a bugbear of mine over the last few years has been to witness a number of poetic projects that were researched and written with assistance from ACE or like organisations. Nothing wrong with that in and of itself, but I always end up reading the declaration that ‘This book could not have been written without the generous support of blah-de-blah’ and thinking ‘Really?’ Because I think very often working-class writers are performing that work totally unacknowledged and unsupported because it doesn’t even occur to us to ask for help, or because we wouldn’t know who to ask or how to apply. And there’s a sense in which this is totally unfair, but there’s also a sense in which it produces rare, exciting and autonomous thought.

It proves that we can be the archaeologists, archivists and explorers of our own history and collective experience, without any mediation between ourselves as writers and the knowledge we seek, and the community of readers we are striving to reach. And in that sense, I think Anxious Corporals is not only a didactic work, it is also a hopeful example of what we can learn and what we can create under our own steam. Can you tell me something about your process for writing and researching this book, and share any thoughts you have about the differences between funded research projects and the kinds of self-directed autodidactic research you were engaged in with this book?

AM: I know exactly what you’re getting at here. You’re right, this particular work wasn’t funded in any way, it was a long-standing labour of love researched, written and painstakingly redrafted (over 100 times!) throughout the last three or more years. Having said that, I have received funding for some of my previous poetry books, two Arts Council G4A Awards in consecutive years for Blaze a Vanishing and The Tall Skies (Waterloo, 2013) and an online-only epic polemical poem Odour of Devon Violet (2014-) which has been an ongoing work-in-progress.

I’ve also over the years received grants from other bodies such as the Royal Literary Fund and the Society of Authors, not to work on particular books but as general subsistence support, and I did also acknowledge the Oppenheim-John Downes Memorial Trust for its financial support while I finished Gum Arabic (Cyberwit, India/US, 2020). But certainly for my earlier collections I was fairly unaware of any opportunities for support and it took many years of completely unfunded writing before I came to find out about some of these, mostly through tips from other poets and writers more adept at finding and applying for such things. But it’s not really a creative instinct, I think, to seek out support and funding for your work, even if it becomes a financial necessity (such as ‘time to write’ grants) – poets are perhaps particularly ill-suited to anything so rational and practical as filling out funding applications (though you might be surprised just how adept at this some are!).

It’s also difficult not to be sceptical about the poetry prize culture, since for so long it appears to have been monopolised by a relatively small grouping of perceived ‘top’ presses, which stretches credibility, the best work can’t always be being published by the same six or so imprints (out of tens of dozens), surely…? But there are pecking orders. Certain expectations. Self-fulfilling prophecies. Less than transparent protocols. There’s also the Oxbridge dimension which has never gone away and which has if anything become much more prevalent in the past decade (in every area of culture).

These prizes not only bestow prestige on recipients but also in some cases considerable financial reward, so it can be a double bitter pill for those struggling working-class and marginalised poets who feel they keep missing out on them. (And when I say ‘marginalised’ this also covers those with disabilities, whether physical or mental health issues, which significantly impact on their access to opportunities; ‘underrepresented’ is the term applied today, and I myself have been described before as an ‘underrepresented poet’). Then there’s the domino effect whereby scooping one prize seems to act as a passport to scooping more, often in fairly quick succession. One of the things I’ve observed over the years is that the best networkers, the pushiest, tend to get the best opportunities; it’s all as much to do with first come, first serve as it is with merit. Many of the most gifted poets I’ve known have often been the least pushy and thus the ones who have languished the longest in obscurity with few breaks or openings – perhaps that’s because they’re more focused on their craft than on its marketing.

Walter Gallichan (writing as Geoffrey Mortimer) in his brilliantly witty The Blight of Respectability, which I excerpt extensively in AC, coined some excellent adages on precisely this theme, one which touched on the ‘shy genius’ being shunned by the establishments while the ‘author of mediocre ability’, the ‘adept of claptrap’, gets all the opportunities and plaudits, just as in, as I also mention at this point in AC, the characters of Edwin Reardon (impoverished authentic writer) and Jasper Milvain (networking hack-writer) in George Gissing’s New Grub Street, a novel Gallichan would have no doubt been aware of and probably would have read. So little has changed since their time of writing in the 1890s!

AC was created out of self-directed research, it’s one of the ways I come to poetry, as a response to wide reading on certain subjects, the sources are books I largely sought out or discovered by chance, one of them was on my father’s bookshelves, he being a keen amateur genealogist with a strong interest in social history, and particularly that of the lower middle classes – I might point out here, too, that AC is not only or entirely focused on the historic working classes, it also takes in the lower middle classes, particularly clerks, much of the information sourced from David Lockwood’s rather dry but informative and compendious The Black Coated Worker. As mentioned before, I’d describe my own background as mixed class: materially and financially working-class (even at times underclass) but educationally and attitudinally middle-class, if that makes any sense.

FL: One of my favourite passages from Anxious Corporals contains these elegiac lines for the Pelican imprint:

Turn at ever more frequent intervals to silent trickles

Of the written page, and in those captivating lakes

Of meaning-making, of careful thought and crafted phrase,

Empathetic pools of escape, come to expand their mental plains

There is so much of note in these lines, which read in the first instance like both an elegy for and a celebration of print media itself, for a particular tactile experience of reading. There is also the real sense of the Pelican imprint’s value being in its empathetic reach, its capacity to expand horizons and connect working people in a kind of felt mutuality. This is exactly opposite to the cynically exploited ‘brand’ value of Pelican as a fetishised commodity, a hollow simple, emptied out of meaning, deployed in the service of a weaponised nostalgia.

What I really relish about this final section of the text is how the old Pelicans, surviving in ‘charity shop surplus’ become sources of solidarity and sustenance for the ‘amputees of new/ Imperialism’, for a new vanguard of ‘anxious corporals’. There is deep sadness towards the end of the book for a loss of Pelican, and for the aims and aspirations of an intellectually curious working-class, but I also have a sense of hope: Pelican – like the working classes ourselves – persists, endures by other means. This is also something that is communicated in your muscular and resistive use of language. Would you mind finishing by talking about this germ of hope, and where – if it is coming from anywhere – you see it as coming from?

AM: Where there’s humanity, compassion, and spirit, there’s always hope, in the spirit of poetry, of creativity, of giving, of unconditional love – in this spirit of compassionate opposition, whether it manifests politically in socialism or communism, in liberation theology at the fusion point of Marxism and Christianity, in Christianity as the religion of the poor and oppressed as it was originally, and all other likeminded religions, where there’s imagination and compassion there’s always hope for something better to come, and if we are to save humanity and, indeed, the world on which we depend, then we need to become more compassionate, empathetic, communitarian and, of course, more nurturing of the planet which supports us.

Capitalism, materialism, consumerism all stand in the way of this, and so they must be swept aside, in time they will have to be, simply, if humanity is to survive into any future worth having, whether through human means or those outside of our control.

FL: Thanks so much for talking to me, Alan! I hope that wasn’t too painful.

AM: Not at all, it was a pleasure answering such incisive questions.