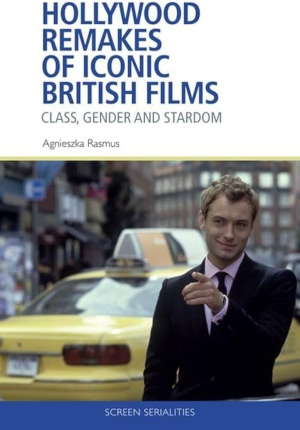

Telling the same story over and over: Hollywood remakes of British films

Jon Baldwin and Brett Gregory review ‘Hollywood Remakes of Iconic British Films: Class, Gender and Stardom’, by Agnieszka Rasmus, (Edinburgh University Press, 2024)

‘I can always take it to the Americans. They're people who recognize young talent, give it a chance, they are.’- Charlie Croker, The Italian Job (1969)

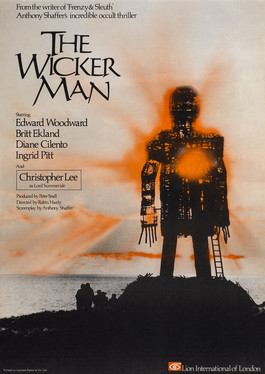

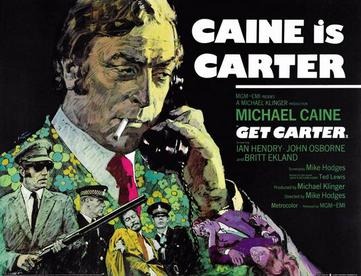

Agnieszka Rasmus makes a excellent contribution to the study of the Hollywood remake with the first book-length study devoted to a select cycle of Hollywood remakes of British cinema classics: Alfie (Gilbert, 1966; Shyer, 2004), Bedazzled (Donen, 1967; Ramis, 2000), The Italian Job (Collinson, 1969; Gray, 2003), Get Carter (Hodges, 1971; Kay, 2000) and The Wicker Man (Hardy, 1973; LaBute, 2006).

As is common knowledge, the Hollywood ‘Dream Factory’ insatiably hunts down, consumes and reconstitutes ideas and narratives from all over the place, and the remaking of films from the past, and from other countries, first began in the US with Siegmund Lubin’s ‘The Great Train Robbery’ in 1904.

The process offers the chance to capitalise on the familiarity and riches of the original production and, to varying degrees of success, an opportunity to update characters, dialogue, iconography and themes etc. for a contemporary younger audience.

In the 21st century new screen technologies, particularly developments in special effects, CGI and AI, have also prompted a succession of remakes that are strategically marketed as ‘enhanced’. For example, the most economically prosperous remake of all time is the photorealistic version of The Lion King (Favreau, 2019), which generated $1,646,106,779 worldwide.

In ‘Hollywood Remakes of Iconic British Films: Class, Gender and Stardom’, the turn-of-the-century remakes that Rasmus explores were nearly all originally produced during London’s ‘Swinging Sixties’. This cycle of movies, which also included Darling (Schlesinger, 1965), The Knack . . . and How to Get It (Lester, 1965), and Blow-Up (Antonioni, 1966), replaced the sober realism and earnest social commentary of British New Wave films such as The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (Richardson, 1962) and This Sporting Life (Anderson, 1963). Due to their hedonistic indulgence in sex and swagger, glamour and glitter, ambition and amorality, they were popular with mainstream audiences, but not particularly with the critics.

In turn, most of their remakes were produced amidst the ideologically-assembled afterglow of ‘Cool Britannia’ in the 1990s: Tony Blair’s New Labour, Britpop’s Oasis versus Blur, Euro ’96, Hugh Grant, Austin Powers, The Spice Girls, Alexander McQueen’s fashion, Damien Hirst and the Young British Artists etc. For instance, the cover of Vanity Fair's March 1997 edition featured Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit lying scantily clad on a Union Jack bedspread with the headline ‘London Swings Again!’ Thus, it can be seen, in line with the continuous capitalist campaign to profit from mediated reproduction, rather than originality, there is nothing as brand new as nostalgia.

Interestingly, these remakes were also released when DVDs were becoming a commodified alternative to VHS and, in turn, Web 2.0 had hit the market. User-generated content, connectivity and collaboration created huge communities of cinephiles – similar to today’s Letterboxd – and they freely voiced their opinions, exchanging knowledge and information. Moreover, the Hollywood remakes of Alfie et al encouraged the re-release of the original productions in DVD format and, as a consequence, both versions fed off each other in a symbiotic, compare and contrast, retail relationship which, for a short time, distracted the contemporary media marketplace.

Indeed, ‘Cool Britannia’ heralded a ‘New Lad’ subculture which attempted to ‘ironically’ portray old-school masculinity in direct contrast with the more sexually ambivalent ‘New Man’ of the 1980s. The magazines of the time – Loaded, FHM and Maxim – objectified women and celebrated male cinematic ‘rogues’ such as Gary Oldman and Oliver Reed, and posters of Michael Caine’s psychopathic London gangster from Get Carter began to adorn young men’s bedrooms and their online profiles; his hyper-masculinity, blokey nature, and overt sexism both steering and salving their emerging machismo.

In the Hollywood remakes of The Italian Job and Get Carter Mark Wahlberg and Sylvester Stallone re-appropriate Michael Caine’s working-class gangsters respectively. As a consequence, the movies morph into star vehicles, and the narrative and genre are shifted to accommodate this predictable Hollywood trope. That is, both remakes endorse heteronormative relations, and any subversive elements present in the originals are ushered into the background.

While Sylvester Stallone’s ‘nice guy’ portrayal in Get Carter can be seen to be a failed attempt to reboot his declining screen image by way of his spectacular physique – The New York Times deemed the film to be ‘pointless’ – it could be argued that the remake of The Italian Job is more interesting. This is mainly because it presents a more balanced approach to gender representation than the inherent misogyny of its 1960s progenitor. This is achieved by activating and elevating the role of its female lead, Stella Bridger (Charlize Theron), in reaction to the original passive portrayal of Lorna (Maggie Blye) as a ‘dolly bird’.

So Stella is a professional safecracker whose skills are essential for the narrative’s heist and, as a result, she wins over the all-male criminal gang. As Rasmus qualifies however, ‘Stella is a progressive young woman, yet she remains visually objectified’ and, ultimately, the plot is reduced to a heteronormative action/love story. For instance, the classic cliff-hanger which concludes the original – ‘Hang on a minute, lads. I've got a great idea…’ – is made redundant by Wahlberg and Theron travelling to Venice with their loot to ‘live happily ever after’.

In turn, Wahlberg’s Charlie Croker offers a version of Hollywood masculinity that is somewhat unthreatening since he uses his brains, rather than his muscles, to solve problems. Moreover, his democratic leadership stands in contrast to the original’s class divisions; a corporate gangster culture with an officious and bureaucratic hierarchy is replaced with scenes and themes of bonhomie and camaraderie.

Rasmus reminds us that remakes are like any other form of adaptation in that they involve an acknowledged transposition of a recognisable work and are both a creative and interpretive act of appropriation. Like the genre film, remakes produce pleasure in terms of repetition with variation, recognition, remembrance, and change. Therefore, they welcome comparison as they implicitly and explicitly acknowledge their predecessors. If sequels and prequels are about ‘never wanting a story to end’, then remakes are about ‘wanting to retell the same story over and over in different ways.’

Each chapter in the book considers each of the five pairs of films by recalling their production, distribution, exhibition, and reception. Significantly, it identifies that such films can provide, inadvertently or not, a commentary on wider socio-cultural changes and developments as they illuminate anxieties at the heart of their original. For example, aristocracy and authority figures no longer dominate British cinema like they did in the 1960s and 1970s, and are now frequently mocked and undermined instead.

Overall, Rasmus’ book could be far more successful than the cycle of remakes she focuses upon. Different cultures, socio-historical periods, audience expectations, genre conventions, directorial styles, aesthetic orientations, identity politics, and industry practices are interrogated appropriately, and it is well worth a read as a result.