Nae Pasaran: They Did Not Pass

John Green reviews a new film about the solidarity and courage of some Scots engineering workers who took action against the Chilean military coup of 1973.

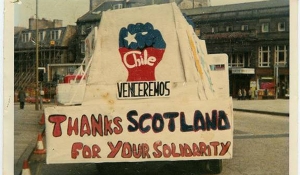

Nae Pasaran tells the incredible but true story of the Scots workers who, from the other side of the world, managed to ground half of Chile’s air force, in the longest single act of solidarity against Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship following the 1973 fascist coup.

The feature-length documentary from young Chilean film-maker Felipe Bustos Sierra charts the story of how, in 1974, a small group of workers at the Rolls Royce aircraft factory in East Kilbride, led by Bob Fulton, Robert Somerville, Stuart Barrie and John Keenan, took the decision not to refurbish Hawker Hunter aircraft engines destined to be returned to Chile.

They were engines from the planes that had been used to bomb the Moneda Palace in Santiago and murder President Allende. Fulton had seen the images of people packed into Santiago’s football stadium and Chilean air force jets strafing the palace and now one of the engines from those very same planes was right there in his factory, waiting to be refurbished.

These workers were not prepared to be made morally culpable and, at the risk of their livelihoods, they said “No” and they carried the whole workforce with them. Little did they realise that their small but courageous action would reverberate around the world and give renewed hope to those who were imprisoned, tortured and persecuted.

The boycott was only one of many actions taken all over the world in protest against Pinochet's dictatorship, but a highly significant one. Bustos Sierra decided that this was a story that had to be told. He tracks down the key men, now retired, and persuades them to retell their story.

Then he takes the thread to Chile, with interviews with those who experienced the horrors of the Pinochet dictatorship and who were given hope by the action of these anonymous Scottish workers.

He also interviews the former chief of the air force under Pinochet, still arrogantly unrepentant, but who admits that the Scottish workers’ action had a significant impact on the Chilean air force’s capabilities. It was dependent on British-supplied Hawker Hunter aircraft and the refurbished engines.

As a moving coda, Bustos Sierra manages to trace one of the Rolls Royce engines, now rusting in a Chilean scrapyard, and transports it back to East Kilbride to serve as a memorial to these men. They are also presented with Chile’s highest honour by the Chilean ambassador in a moving ceremony in East Kilbride.

The boycott endured for four years but the Scottish workers were never, until now, aware of the impact their action had. For them it was simply a matter of conscience and an act of solidarity.

Bustos Sierra — himself the Scotland-based son of a Chilean exile — reunites these inspirational workers to hear their story. With unprecedented access, Nae Pasaran also ventures much further to detail the horrors of the Pinochet years, giving the historical and international context, and meets survivors of the period to hear the Chilean side of the story.

Although over an hour long, the film maintains the tension of a story which is at times deeply emotional, full of humanity and historically informative. This is history as it should be told and reminds us of how vital working-class solidarity is and how effective it can be, particularly in the world we are now living in, when some people are being categorised as of less worth than others and are denied basic human rights.

Don’t miss this film. Ask for it to be shown in your local cinemas and spread the word.

For details of screenings, visit naepasaran.com. This review first appeared in the Morning Star.